Jhelum District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Jhelum District

Jehlam

District in the Rawalpindi Division of the Punjab, lying between 32 degree 27' and 33 degree 15' N. and 72 degree 32' and 73 degree 48' E., with an area of 2,813 square miles. Its length from east to west is 75 miles, its breadth increasing from 2 miles in the east to 55 in the west It is bounded by the Districts of Shahpur and Attock on the west, and by Rawalpindi on the north ; while the Jhelum river separates it from Kashmir territory on the north-east, and from Gujrat and Shahpur on the south-east and south.

Physical aspect

The District falls naturally into three divisions. Of these the north- eastern, which includes the Chakwal tahsil and the narrow Pabbi tract in the north of the Jhelum tahsil, is a wide and fertile plateau ranging from 1,300 to 1,900 feet above the

sea, with a decided slope to the north-west, until at the Sohan river it reaches the boundary of the District. This plateau is intersected by numerous ravines, which, with the single exception of the Bunha torrent on the east, drain into the Sohan. To the south it culminates in the Salt Range, which runs in two main ridges from east to west, now parallel, now converging, meeting in a confused mass of peaks east of Katas and opening out again. Between these ranges is a succession of fertile and picturesque valleys, set in oval frames by the hills, never more than 5 miles in width and closed in at either end. The Salt Range runs at a uniform height of 2,500 feet till it culminates in the peak of Chail (3,701 feet). At the eastern end of the Salt Range two spurs diverge north-eastwards, dividing the Jhelum tah&l into three parallel tracts.

The northernmost of these, the Pabbi, has already been described. The central tract, lying between the Nili and the Tilla spurs, is called the Khuddar, or * country of ravines.' The whole surface seems to have been crumpled up and distorted by converging forces from the north and south. Lastly, south of the Tilla range, lies the riverain tract, which extends along the river from Jhelum town in the north-east to the Shahpur border. Broken only near Jalalpur by a projecting spur of the Salt Range proper, this fertile strip has a breadth of about 8 miles along the southern boundary of the Jhelum and Pind Dadan Khan tahsils.

The greater part of the District lies on the sandstones and con- glomerates of the Siwalik series (Upper Tertiary), but towards the south the southern scarp of the Salt Range presents sections of sedimentary beds ranging from Cambrian upwards. The lowest bed contains the salt marl and rock-salt. The former is of unknown age, but appears to be overlain by a purple sandstone, followed by shales containing Lower Cambrian fossils. These are again overlain by the magnesian sandstone and salt pseudomorph zone of the Punjab.

The latter zone is followed by a boulder-bed and shales, and sand-

stones of Upper Carboniferous or Permian age, overlain by Lower

Tertiary sandstone and Nummulitic limestone. In the eastern part

of the Salt Range, the fossiliferous Productus limestone and ceratite

beds are apparently absent, and there is a gap in the geological

sequence between Lower Permian and Tertiary. Coal occurs in the

Lower Tertiary beds at Dandot and Baghanwala .

The flora of the lower elevation is that of the Western Punjab ; in the north-east the Outer Himalaya is approached; while the Salt Range has a vegetation of its own which combines rather different elements, from the north-west Indian frontier to the hills east of Simla. Trees are rare, except where planted or naturalized, but the phulahi {Acacia modestd) is abundant in the hills and ravine country. At Khewra the salt outcrops have a special flora, found in similar places in Shahpur and across the Indus.

In the hills hyenas, jackals, and a few wolves and leopards are found. The Salt Range is a favourite haunt of the urial; ravine deer’ (Indian gazelle) are plentiful in the western hills. Sand-grouse, partridge (black and grey), chikor, and sisl are met with, and a great variety of wild-fowl haunt the Jhelum. Flocks of flamingo are found on the Kallar Kahar lake, and quail are not uncommon. Dhangrot on the Jhelum is a well-known place for mahseer fishing.

The climate is good. In the hills the heat is never extreme, though the adjoining submontane tract is one of the hottest in the Punjab. The rest of the District has the ordinary climate of the Western Punjab plains — excessive heat for half the year, with a long and bracing cold season, and the usual feverish seasons.

In the winter a bitter north

wind prevails in the Salt Range and the northern plateau, light snow

on the hills is not uncommon, and once or twice in a generation

a heavier fall extends to other parts of the District. Here and there

guinea-worm, due to bad water, severely affects the population. The

annual rainfall varies from 16 inches at Pind Dadan Khan to 24 inches

at Jhelum. Of the fall at Jhelum, 6 inches are received in winter and

18 inches in the summer months. The local distribution is very

variable. The tracts at the foot of the Salt Range often remain dry

while heavy rain is falling in the hills, and rain in the east of the

Jhelum tahsil sometimes does not extend to the west.

History

The early annals of Jhelum present more points of interest than its records in modern times. Hindu tradition represents the Salt Range as the refuge of the Pandavas during the period of their exile, and every salient point in its scenery is connected with 8 ry " some legend of the national heroes.

The conflict between Alexander and Poms probably took place in or near the present District, though the exact spot at which the Macedonian king effected the passage of the Jhelum (or Hydaspes) has been hotly disputed. Sir Alexander Cunningham supposed that the crossing was at JaUllpur, which he identified with the city of Bucephala ; and that the battle with Porus — a Greek corruption of the name Purusha — took place at Mong, on the Gujrit side, close to the field of Chiltanwala. A later writer (Mr. V. A. Smith) holds that the battle-field was ten miles north-east of Jhelum town. When the brief light cast upon the country by Arrian and Curtius has been withdrawn, we have little information with reference to its condition until the Muhammadan conquest. In the interval it must have passed through much the same vicissitudes as the neighbouring District of Shahpur.

The Janjuas and Jats, who, along with other tribes, now hold the Salt Range and the northern plateau respectively, appear to have been the earliest inhabitants. The former are doubtless pure Rajputs, while the Jats are perhaps their degenerate descendants. The Gakhars seem to represent an early wave of conquest from the west, and they still inhabit a large tract in the east of the District ; while the A wans, who now cluster in the western plain, are apparently later invaders.

The Gakhars were the dominant race at the period of the first

Muhammadan incursions; and they long continued to retain their

independence, both in Jhelum itself and in the neighbouring District

of Rawalpindi. During the flourishing period of the Mughal dynasty,

the Gakhar chieftains were among the most prosperous and loyal

vassals of the house of Babar. But after the collapse of the Delhi

empire, Jhelum fell, like its neighbours, under the sway of the Sikhs.

In 1765 Gujar Singh defeated the last independent Gakhar prince, and

reduced the wild mountaineers of the Salt Range and the Murree Hills

to subjection.

His son succeeded to his dominions until 18 10, when he fell before the irresistible power of Ranjlt Singh. Under the Lahore government the dominant classes of Jhelum suffered much from fiscal exactions ; and the Janjaa, Gakhar, and A win families gradually lost their landed estates, which passed into the hands of their Jat depen- dants. The feudal power declined and slowly died out, so that at the present time hardly any of the older chieftains survive, while their modern representatives hold no higher post than that of village headman.

In 1849 Jhelum passed with the rest of the Sikh territories into the power of the British. Ranjtt Singh, however, had so thoroughly subjugated the wild mountain tribes who inhabited the District that little difficulty was experienced in reducing it to working order. In 1857 the 14th Native Infantry stationed at Jhelum town mutinied, and made a vigorous defence against a force sent from Rawalpindi to disarm them, but decamped on the night following the action, the main body being subsequently arrested by the Kashmir authorities, into whose territory they had escaped. No further disturbance took place. The subsequent history of Jhelum has been purely fiscal and adminis- trative. On April 1, 1904, the tahsll of Talagang was detached from the District and incorporated with the new District of Attock.

The country is still studded with interesting relics of antiquity, among which the most noticeable are the ruined temples of Katas, built about the eighth or ninth century a.d., and perhaps of Buddhist origin.

Other religious ruins exist at Malot and Shivganga ; at Jhelum town an old mound has yielded utensils of Greek shape, and the remains of an old Kashmiri temple ; while the ancient forts of Rohtas, Girjhak, and Kusak, standing on precipitous rocks in the Salt Range, are of deep interest for the military historian. Indeed, the position of Jhelum on the great north-western highway, by which so many conquerors have entered India, from the Greek to the Mughal, has necessarily made it a land of fortresses and guarded defiles, and has turned its people into hereditary warriors.

Population

The population of the District at the last three enumerations was : (1881) 494i499, ( l8 9 1 ) 5 14,090 ,and (190l ) 5 OI -,424, dwelling in 4 towns and 888 villages. It decreased by 2-4 per cent, during the last decade.

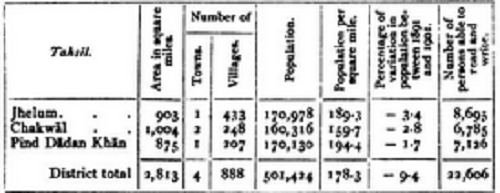

The District is divided into the three tahstls of Jhelum, Pind Dadan Khan, and Chakwal, the head-quarters of each being at the place from which it is named. The chief towns are the municipalities of Jhelum, the administrative head-quarters of the District, and Pind Dadan Khan. The following table shows the chief statistics of population in 1901 : —

Note.— The figures for the areas of tahsils are taken from revenue returns. The total District area is that given in the Census Report,

Muhammadans number 443,360, or 89 per cent, of the total ; Hindus, 43,693; and Sikhs, 13,950. The language of the people is Western Punjabi.

The most numerous tribe is that of the Jats, who number 73,000,

or 14 per cent of the total population. Next to them numerically are

the Rajputs (53,000) and Awans (51,000). Other important agricul-

tural castes are the Malifirs (23,000), Mughals (21,000), Gujars (20,000),

Gakhars (11,000), and Kahutas (10,000), the latter almost entirely

confined to this District. Saiyids number 13,000. Of the com-

mercial and money-lending classes, the most numerous are the KhattrTs

(31,000), Aroras returning only 9,000.

Brahmans number 5,000. Of

the artisan classes, the Julahas (weavers, 23,000), Mochls (shoemakers

and leather-workers, 19,000), Tarkhans (carpenters, 14,000), Kumhars

(potters, 1 0,000), Lohars (blacksmiths, 8,000), and Telis (oil-pressers,

7,000) are the most important. Kashmiris number 12,000. The

chief menial classes are the Musallls (sweepers, 18,000), Nais (barbers,

9,000), Machhis (fishermen, bakers, and water-carriers, 6,000), and

Dhobls (washermen, 5,000). The Lilla Jats (1,000), an agricultural

tribe found only in this District, also deserve mention. Of the whole

population, 61 per cent, are supported by agriculture. The leading

tribes — Gakhars, Awans, Janjuas, and other Rajputs — enlist freely in

the Indian army.

The American United Presbyterian Mission has a branch at Jhelum

town, where work was started in 1873, and the Roman Catholic

missionaries maintain a school at Dalwal in the Salt Range. In 190 1

the District contained 1 1 1 native Christians.

Agriculture

The area irrigated by artificial means is a tenth of that cultivated in the Pind .Dadan Khan tahsil but only one per cent, in the Chakwal and Jhelum tahsils. Cultivation thus depends on the local rainfall, eked out by the drainage from higher ground.

The country is in parts seamed by torrent beds, and the soil varies from the infertile sand brought down by them to a rich loam and the stony soil of the hill-sides. In the greater part of the unirrigated land a spring crop is followed by an autumn crop; but the best land receiving drainage from higher ground is generally reserved for the spring, and in the tract under the hills in Pind Dadan Khan the lands for the autumn and spring harvests are kept separate.

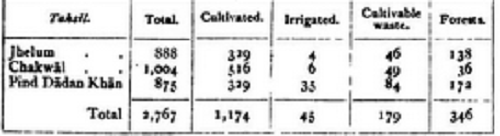

The District is chiefly held by communities of small peasant pro- prietors, large estates covering only about 103 square miles. The area for which details are available from the revenue records of 1903-4 is 2,767 square miles, as shown on the next page.

The chief crops of the spring harvest are wheat, barley, gram, and oilseeds, the areas under which in 1903-4 were 477, 26, 34, and 80 square miles respectively ; and in the autumn harvest, jowda y bajra % and pulses, which covered 16, 207, and 28 square miles respectively. Between the settlements of 1864 and 1881 the cultivated area increased by 41 per cent., while the area cultivated at the settlement of 1 901 showed an increase of 13 per cent, on that of 1881. The new cultivation of the last twenty years is, however, greatly inferior to the old, and there is but little prospect of further extension. Loans for the construction of wells are extremely popular, and Rs. 25,700 was advanced under the Land Improvement Loans Act in the District as now constituted during the five years ending 1904.

The Dhanni breed of hojses found in the Dhan or plateau north of the Salt Range has long been held in high estimation, being mentioned in the Ain-i-Akbarl, while good horses are found all over the District. The Army Remount department maintains 4 horse and 11 donkey stallions, and the District board 2 horse stallions. The Dhanni breed of small cattle is also well-known. Camels are largely used for carrying burdens, but the breed is poor. Both the fat-tailed and ordinary sheep are kept, and the goats are of a fair quality.

Of the total area cultivated in 1903-4, 45 square miles, or 3*8 per cent., were classed as irrigated by wells and canals. In addition, 47 square miles, or 4 per cent, of the cultivated area, are subject to inundation from the Jhelum. The wells, which number 4,781, are chiefly found along the river and in the level portion of the Jhelum tahsal; they are all worked by cattle with Persian wheels. Canal- irrigation is at present confined to two small cuts in the Pind Dadan Khan tahsil, one Government, the other private ; but it is proposed to absorb the former in a larger canal commanding about 50,000 acres. The cultivation from the hill streams is unimportant, though where it exists no land is so profitable. Much of the unirrigated land is embanked and catches the drainage from higher ground.

The District contains 260 square miles of 'reserved' and 97 of unclassed forest under the Forest department, besides 43 square miles of unclassed forest and waste land under the Deputy-Commissioner, and one mile of military reserved forests. These consist mainly of the scattered scrub of phuldhi, wild olive, ukhanh, and leafless caper, which clothe the hills. Some of the forest lands are stretches of alluvial grazing-ground, known as Mas, along the Jhelum.

In 1904-5 the revenue from the forests under the Forest department was Rs. 82,000, and from those under the Deputy-Commissioner Rs. 9,000. Salt is found in large quantities in the Salt Range. It is excavated at Khewra and Nurpur, but outcrops are found in many places; and, in addition to the employes of the Khewra mines, a large pre- ventive staff has to be maintained to. prevent salt from being mined. Coal occurs in many places in the Salt Range.

It is mined at Dandot by the North-Western Railway, and by a private firm at Baghanwala. Gypsum occurs in the marl beds above the salt strata of the Salt Range. Stone for road-making or railway ballast is plentiful, and good sandstone and limestone for building are frequently met with. Clay for pottery is also found. Fragments of copper and earthy iron hematites occur, but are quite unimportant Sulphuret of lead or galena is found in small nodules in two or three localities. Quartz crystals are found in the gypsum of the Salt Range. Gold is washed in the beds of the torrents which flow into the Sohan, but the out-turn is insignificant.

Trade and communication

The District possesses no arts or manufactures of any importance.

Boat-building is carried on at Jhelum and at Pind Dadan khan, and brass vessels and silk lungis are made at the latter town. Water-mills are frequently used for grinding corn.

Jhelum town is an important timber depot, being the winter head- quarters of a Kashmir Forest officer who supervises the collection of the timber floated down the river. There is a large export of timber by both rail and river and of salt from Khewra, but otherwise the trade of the District is unimportant. Brass and copper ware is exported from Pind Dadan Khan.

Stone is also exported, and in good seasons

there is a considerable export of agricultural produce. The chief

imports are piece-goods and iron. Jhelum town and Pind Dadan

Khan are the centres of trade, and a considerable boat traffic starts

from the latter place down the river. The completion of the railway

system, however, has already ruined the trade of Pind Dadan Khan,

and is fast reducing Jhelum town to the position of a local depot.

The main line of the North-Western Railway traverses the east of the District, passing through Jhelum town, while the Sind-Sagar branch runs through the south of the Pind Dadan Khan tahsil with a branch to Khewra, whence a light railway brings down coal from Dandot. A branch from the main line to Chakwal has been suggested, but has not been surveyed. Owing to the rugged nature of the country, the roads are not good.

The only road used for wheeled traffic is the grand trunk road, which traverses the District by the side of the main line of rail ; elsewhere pack animals are used. The only other route on which there is much traffic is that leading from Pind Dadan Khan by Khewra to Chakwal. The Jhelum is navigable to about 10 miles above Jhelum town. It is crossed by a railway bridge with a track for wheeled traffic at Jhelum, by another with a footway only m the Find Dadan Khan tahsil , and by fourteen minor ferries.

Famine

The District suffered from the great chdhsa famine of 1783, and there was famine in 1813 and 1834. Locusts did a great deal of damage in 1848. In 1 860-1, though the scarcity in .

other parts of the Province caused prices to rise, the crops here did not fail to any serious extent. In 1896-7 there was considerable distress, and test works were started, but were not largely attended. The worst famine since annexation was that of 1899-1900. It was, however, more a fodder than a grain famine ; and though there was acute distress and test works were opened, it was not considered necessary to turn them into famine works. The greatest daily number relieved in any week was 3,955, and the total expenditure was Rs. 39,000.

Administration

The District is divided into the three tahsils of Jhelum, Find Dadan Khan, and Chakwal, each under a tahsildar and a naib- tahsildar. The Deputy-Commissioner is aided by . .

three Assistant or Extra-Assistant Commissioners, of whom one is in charge of the Find Dadan Khan subdivision and another of the District treasury.

The Deputy-Commissioner as District Magistrate is responsible for criminal justice. Civil judicial work is under a District Judge, and both officers are subordinate to the Divisional and Sessions Judge of the Jhelum Civil Division. There are three Munsifs, one at head- quarters and one in each tahsiL The predominant form of crime is cattle-theft, while murders are also frequent.

The Sikh demand for land revenue cannot be shown with any accuracy. They took what they could get, but their average receipts during the last four years of their rule would seem to have been 7 lakhs. After the second Sikh War, when Jhelum passed into British possession, a summary settlement was made, yielding slightly less than the Sikh assessment. In 1852 a second summary settlement was undertaken, to correct the more obvious inequalities of the first.

On the whole, both of these worked well, though some proprietors refused to pay the revenue fixed, and surrendered their proprietary rights. The first regular settlement, made in 1855-64, assumed half the net ‘ assets' as the share of Government, and fixed the demand at 6 ½ lakhs. The next settlement (1874-81) raised the revenue by 18 per cent.; but this was easily paid, until a succession of bad harvests made large suspensions and some remissions necessary.

In the present settlement (1895- 1 901) a further increase of 26 per cent, has been taken, but it is recognized that frequent suspensions will be needed. The average assessment on 'dry’ land is Rs. 1-3 (maximum Rs. 2, minimum. 6 annas), and on ‘ wet ' land Rs. 3-2 (maximum Rs. 5, minimum Rs. 1-4). The demand on account of land revenue and cesses in 1903-4 for the District as now constituted was 8-8 lakhs. The average size of a proprietary holding is 18 acres.

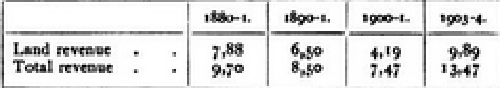

The collections of land revenue alone and of total revenue are shown below, in thousands of rupees : —

NOTE,— These figures arc for the District as constituted before the separa- tion of the Talagang tahsil 1904. •

The District contains two municipalities, Jhelum and Pind Dadan Khan, and one 'notified area,’ Chakwal. Outside these, local affairs are managed by the District board, the income of which is mainly derived from a local rate, and amounted in 1903-4 to Rs. 93,000. The expenditure was Rs. 88,000, the principal item being education.

The regular police force consists of 450 of all ranks, including 8 cantonment and 81 municipal police, and the Superintendent usually has 4 inspectors under him. Village watchmen number 615. There are 14 police stations and 2 road-posts. The District jail at head- quarters has accommodation for 295 prisoners.

The District stands sixth among the twenty-eight Districts of the Province in respect of the literacy of its population. In 1901 the proportion of literate persons was 4-5 per cent. (8-5 males and 0.4 females). The number of pupils under instruction was 3,964 in 1880-1, 12,026 in 1890-1, 12,386 in i90o-i,and 14,869 m 1903-4 . In 1904-5 the number of pupils in the District as now constituted was 12,144.

In the same year the District contained 9 secondary and 95 primary (public) schools, and 3 advanced and 212 elementary (private) schools, with 454 girls in the public and 392 in the private schools. There are two Anglo-vernacular high schools, at Jhelum town and Pind Dadan Khan. The total expenditure on education in 1904-5 was Rs. 54,000.

Besides the civil hospital at Jhelum town, the District contains four outlying dispensaries. In 1904 a total of 76,560 out-patients and 1,451 in-patients were treated, and 2,859 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 15,000, District funds contributing Rs. 6,000 and municipal funds Rs. 9,000. The American Presbyterian Mission also maintains a hospital at Jhelum.

The number of successful vaccinations in 1903-4 was 14,498, repre-

1 All these figures apply to the District as constituted before the separation of the Talagang taksil in 1904. senting 28.9 per 1,000 of the population. The Vaccination Act has been extended to the towns of Jhelum and Pind D&dan Khan.

[W. S. Talbot, District Gazetteer (in press); Settlement Report (1902); and General Code of Tribal Custom in the Jhelum District (1901).]