Sambhal Town

Contents |

Sambhal Town

A 1908 British account

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Head-quarters of the tahsil of the same name in

Moradabad District, United Provinces, situated in 28 35' N. and

78 34' E., 23 miles south-west of Moradabad city by a metalled road.

Population (1901), 39,715. The town is believed by the Hindus to

have existed in the three epochs (yuga) preceding the present or Kali

Yuga, at the end of which the tenth incarnation of Vishnu will appear

in Sambhal. Many ancient mounds exist in the neighbourhood, but

have not been explored. Tradition relates that Prithwi Raj of Delhi

finally defeated Jai Chand of Kanauj close to Sambhal, and an earlier

battle is said to have taken place between the Raja of Delhi and

Saiyid Salar. Kutb-ud-dm Aibak reduced the neighbourhood for a

time ; but the turbulent Katehriyas repeatedly engaged the attention

of the early Muhammadan kings, who posted a governor here. In

1346 the governor revolted, but was speedily crushed. Firoz Shah III

appointed an Afghan to Sambhal in 1380, with orders to invade

Katehr every year and ravage the whole country till Khargu, the Hindu

chief, who had murdered some Saiyids, was given up. In the fifteenth

century Sambhal was the subject of contest between the sovereigns of

Delhi and the kings of Jaunpur, and on the fall of the latter Sikandar

Lodi held his court here for some years. Babar appointed his son,

Humayun, to be governor of the place, and is said to have visited

it himself. Under Akbar Sambhal was the head-quarters of a sarkdr^

but in the reign of Shah Jahan its importance began to wane and

Moradabad took its place. In the eighteenth century Sambhal was

chiefly celebrated as the birthplace of the Pindari, Amir Khan, who

raided Rohilkhand in 1805 and afterwards founded the State of TONK.

The town site is scattered over a considerable area, and contains a mound marking the ruins of the old fort. No building stands on this except a mosque, claimed by the Hindus as a Vaishnava temple, but in reality a specimen of early Pathan architecture in which Hindu materials were probably used. The mosque contains an inscription recording that it was raised by Babar; but doubts have been cast on the authenticity of this. There are many Hindu temples and sacred spots in the neighbourhood. The town contains a tahsili^ a munsifi) a dispensary, and a branch of the American Methodist Mission. It has been a municipality since 1871. During the ten years ending 1901 the income and expenditure averaged Rs. 21,000. In 1903-4 the income was Rs. 30,000, chiefly from octroi (Rs. 23,000); and the expenditure was Rs. 29,000. Refined sugar is the chief article of manufacture and of trade, but other places nearer the railway have drawn away part of its former commerce. Wheat and other grain and ghi are also exported, and there is some trade in hides. Combs of buffalo horn are manufactured. The tahsill school has 142 pupils, and the municipality manages two schools and aids seven others with 349 pupils.

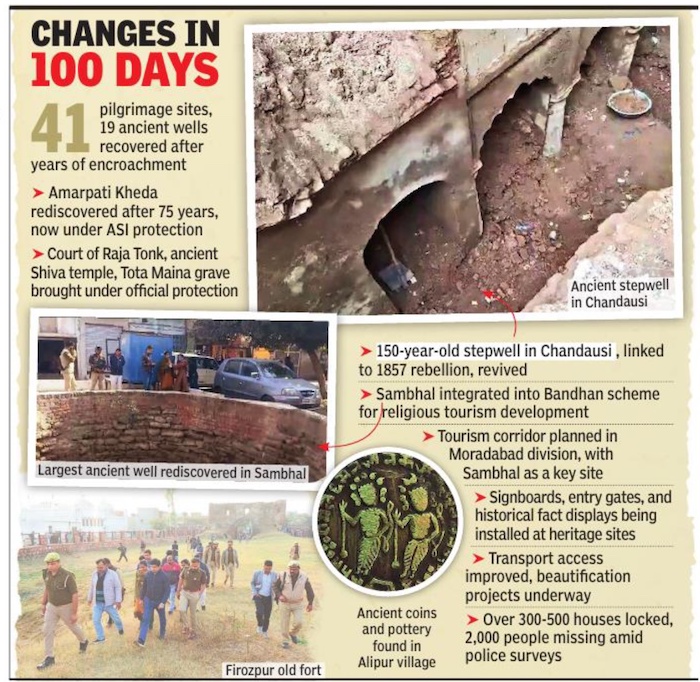

Changes in the town

Kanwardeep Singh, March 5, 2025: The Times of India

From: Kanwardeep Singh, March 5, 2025: The Times of India

Bareilly : For years, Sambhal had been a city known for what it had lost. Ancient temples, pilgrimage sites, wells, some dating back centuries, had vanished under layers of alleged illegal construction and disrepair, their histories obscured by time and circumstance. But in these past months, the administration, working alongside the Archaeological Survey of India, has rewritten that narrative, bringing 41 pilgrimage sites and 19 ancient wells back into public memory.

In the hundred days since a court-monitored ASI survey of the 16th century Mughal-era Sambhal’s Shahi Jama Masjid turned into a flashpoint of violence, the city has embarked on an unexpected transformation. What was once a site of unrest has now become the stage for an ambitious “heritage revival”. The officials undertook a sweeping survey of the city’s “encroached and forgotten landmarks”, unearthing a past that had long been buried under decades of neglect.

Among the sites rediscovered is the court of Raja Tonk in Saraitareen’s Darbar locality, once a vibrant centre of power but now reclaimed from the shadows of modern buildings. The Tota Maina grave, an ancient Shiva temple, and a 150-year-old stepwell in Chandausi, with its fabled underground tunnel linked to the 1857 rebellion, have also come under official protection. Perhaps most striking is the “reappearance” of Amarpati Kheda, an ASI-protected site that had been considered lost for 75 years. It is said to house Dadhichi Ashram and 21 samadhis, including one believed to belong to Prithviraj Chauhan’s guru, Amarpati. Sambhal’s story is not just one of historical recovery but of reinvention. The city, believed to be the place where Kalki, the 10th avatar of Lord Vishnu, will be born, is now a cornerstone of UP’s religious tourism vision. The CM-led dispensation has folded its revival into the Bandhan scheme, planning to integrate these heritage sites into a tourism corridor spanning the Moradabad division. “Officials have accelerated efforts to reclaim and restore lost sites. Sambhal holds a special place because of its religious significance, and we are ensuring its history is not only preserved but also experienced,” said a senior official.

That experience is now being carefully curated. Manibhushan Tiwari, executive officer of the Sambhal Municipal Council, along with DM Rajender Pensiya, has been leading visits to each recovered site, mapping out the logistics of their restoration. “Each location will have a gate reflecting its identity, with historical facts displayed at the entrance,” Tiwari said. “We want visitors to walk into these places and feel the weight of their significance. The incarnations of Lord Kalki will also be highlighted, creating a deeper connection to our past.” Transportation is being improved, signboards installed, and the architectural character of the sites is revived to balance preservation with accessibility.

Yet, for all its progress, the city remains unsettled. An 80-year-old resident, reluctant to share his name, said, “For 20 years, people lived in peace. Now, fear has crept back in. Many have left their homes. Loudspeakers have been removed from mosques. Even during Ramzan, the azaan is not allowed in some places.” The authorities say this fear is misplaced, a side effect of the crackdown after the riots. A senior police officier painted a stark picture of the aftermath. “Over 300 to 500 houses are locked, and at least 2,000 people are missing,” he said. “Not all of them were involved in the violence, but they panicked when the police began door-to-door surveys. Many families have been living on land they don’t have papers for — land encroached after the 1978 riots. We have already freed the properties of three families from illegal possession. More will follow.”

Construction of a new police outpost opposite the Shahi Jama Masjid commenced on Dec 28. The outpost is likely to be named Satyavrat. In the meantime, 79 people have been arrested in connection with the Nov 24 clashes, and charges have been filed in six out of the 12 registered cases.

History

1924: communal tension and Nehru’s report

From: January 10, 2025: The Print

From: January 10, 2025: The Print

From: January 10, 2025: The Print

From: January 10, 2025: The Print

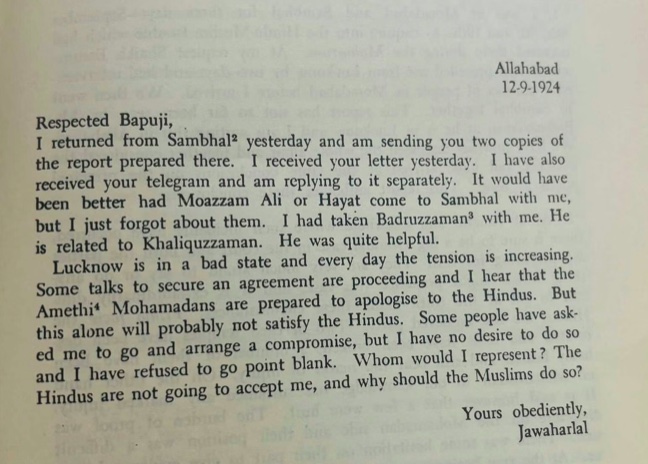

MK Gandhi sent Jawaharlal Nehru to Sambhal in 1924 to study an incident of communal violence. Nehru describes the Jama Masjid as a “fine temple” built by Prithvi Raj.

New Delhi: The communal clash in Sambhal had a clear victim—the Hindus. A report said Hindus are the aggrieved party.

This report wasn’t published in 2024. It’s from 1924 — and its author was Jawaharlal Nehru.

A whole century before Sambhal took centre stage in the national conversation for a communal clash over surveying the origins of the town’s Jama Masjid, it was a cause of great concern for MK Gandhi and the Congress party. So much so that Gandhi sent Nehru to Sambhal to study the incident.

“Owing to their large majority in the town and neighbourhood, and for other reasons, Muslims have all along been top dogs in Sambhal,” Nehru observed in his 13-page report written in September 1924.

Nehru wrote a short letter to Gandhi, which he sent along with two copies of his report. In the letter, he describes how he was asked to mediate between Hindus and Muslims — and how he said he had no desire to “arrange a compromise”.

“Whom would I represent?” Nehru asked Gandhi in a letter after the visit. “The Hindus are not going to accept me, and why should the Muslims do so? Yours obediently, Jawaharlal.”

Nehru arrived in Sambhal via Lucknow on 8 September 1924, after a group of Hindus and Muslims clashed in the town during Mohurrum, which coincided with an annual fair held in the town. He spent the next three days speaking with Hindus and Muslims at every level — from members of the local administration to shopkeepers to priests and sadhus.

Not much has changed between the Sambhal of 1924 and 2024, according to Nehru’s report. The town was Muslim majority then as it is now. Both Hindu and Muslim communities are on tenterhooks on the eve of every religious commemoration both then and now, afraid that violence would break out. And the Jama Masjid was a bone of contention even then.

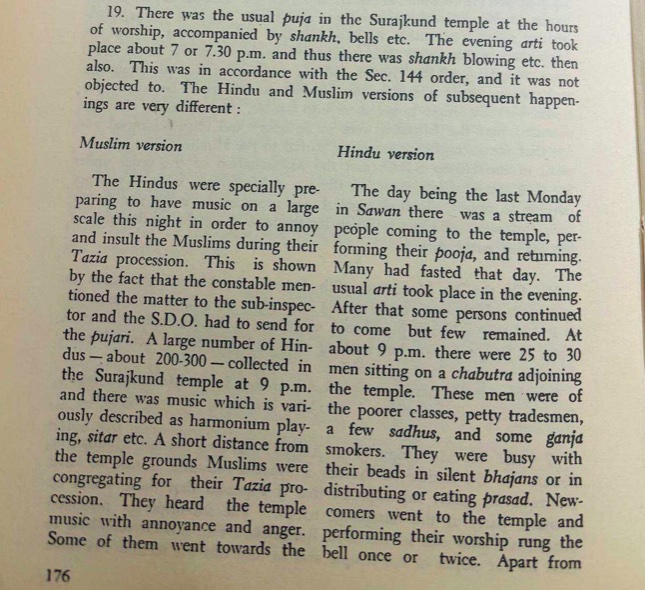

The 13-page report is incredibly detailed, setting the context for the clash that took place. Nehru faithfully reproduces the Muslim version of events side-by-side with the Hindu version, presenting them as comparative columns. The details of the incident are supported by demographic and cultural descriptions of Sambhal and its population, including power dynamics between various communities.

It also gives an insight into the way Nehru approached such conflicts and how he investigated them. In the report, Nehru seems extremely aware of not just his own position in Indian society, but also the precariousness of communal balance in an India that was erupting with all manners of identity crises. It was a time before the idea of Independent India was fully formed.

In his letter to Gandhi, accompanying two copies of the report he’d prepared — written from Anand Bhavan in Allahabad on 12 September 1924 — Nehru briefly describes communal tensions in Lucknow, Amethi and Sambhal. Talks were on to “secure an agreement” between the Hindus and Muslims, and he writes that Muslims are prepared to apologise to the Hindus — but that this alone will not satisfy the Hindus.

The incident in question

The facts of the matter were thus: A local mela conflicted with Mohurrum in Sambhal. In 1923, both communities reached an agreement that the mela would not be held during Mohurrum — but the following year, no such arrangements were made.

On the night of 9 August 1924, a Mohurrum procession took place on a large scale. “Some Hindus as usual took part in the procession,” Nehru notes. But tensions heightened on 11 August, which was the last day of Mohurrum. Many Muslims were upset at music being played and drums being beaten during their period of mourning, and Hindu temples were asked not to play music beyond 9 pm. But tensions broke out over this, and both sides clashed, with violence descending for around two hours. By the end of it, 17 Hindus were hurt and two temples were attacked.

“Prima facie the Hindus are the aggrieved party,” Nehru writes early on in the report. “Two of their temples have been desecrated and idols have been broken; a number of them have been badly beaten and still bear the marks of injury. On the other hand, no Mohamadan to our knowledge has sustained any marked injury. It is said however that a few were hurt.”

Nehru did note that the Hindu side was trying to “improve” upon their version of events by “supplying all manner of details to show premeditation and careful preparation for attack” by the Muslims. They were exaggerating instances of cruelty and improper behaviour by Muslims and also trying to implicate “almost every Mohamadan of note in Sambhal,” as well as local Muslim officials. On the other hand, the Muslims said the Hindus tried to provoke them into an attack.

“The general impression of the evidence is that there was a considerable amount of hard lying on both sides.” The impression he gathered was that of a “courtroom and carefully tutored witnesses repeated a well-prepared story. The two accounts differ materially on almost every important point.”

Nehru’s observations

Nehru describes Sambhal as perhaps one of the most ancient towns in India — even mentioned in the Puranas. He also writes that “it is said that the next avatar will come from Sambhal.”

While the district of Moradabad, he writes, is “notorious for Hindu-Muslim troubles,” he makes note of how important the town was to both Hindus and Muslims.

He describes the Jama Masjid as a “fine temple” built by Prithvi Raj, and notes that according to modern lore, it “was subsequently converted into the principal mosque of the city.” One hundred years later, this mosque still seems to be the central faultline in Sambhal.

All this context precedes his breakdown of the incident in question, neatly presented side-by-side in two columns. The Hindu version is much longer than the Muslim version, crammed with more facts and details — even a “ganja smoker” is described in this. Earlier on in the report, he writes that Hindus were more forthcoming with their version of events than the Muslims — this is despite the fact that he was accompanied on this fact-finding mission by Shaikh Badruzzaman of Barabanki district, who had left Aligarh University to join the non-cooperation movement in 1920.

The report is scathingly honest, and Nehru is clearly concerned by the depth of religious sentiment forcing people to violence.

“The suggestion in the Muslim version that the Hindus themselves must have desecrated their temples and broken their images is pure fancy and not possible to accept without the strongest proofs,” writes Nehru, describing the suggestion as “absurd.” On that night, Hindus were terrified, writes Nehru — “they all locked and bolted their doors and waited anxiously for the morning.”

Similarly, Nehru dismisses the idea that Muslims premeditated the attack. “But one thing is clear that they were resentful and angry and it may be that they were very ready to accept any real or fancied challenge to them,” he conceded.

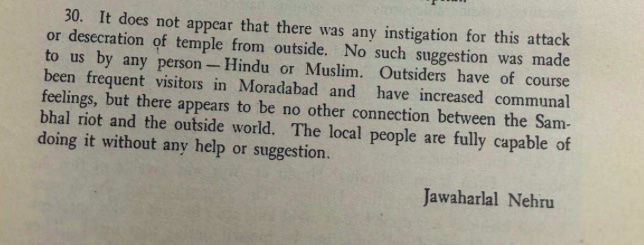

At the end of the meticulous report, Nehru makes his final observations — an opinion on Sambhal that seems to have echoed through the annals of time.

“It does not appear that there was any instigation for this attack or desecration of temple from outside. No such suggestion was made to use by any person — Hindu or Muslim,” writes Nehru bluntly in the concluding paragraph of his report. “Outsiders have of course been frequent visitors in Moradabad and have increased communal feelings, but there appears to be no other connection between the Sambhal riot and the outside world. The local people are fully capable of doing it without any help or suggestion.”

The Sambhal of 1924

Even in 1924, the region had a reputation. Nehru’s descriptions of Sambhal and Moradabad match the belief that the region is a communally sensitive hotspot.

The incident also gives us a glimpse into what religious tensions were like at the time. This particular riot took place a year before the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (R S S) was founded in 1925. It was four years after the non-cooperation movement began and two years after the Chauri-Chaura incident.

“The district of Moradabad is notorious for Hindu-Muslim troubles,” Nehru writes. “Congress work has not prospered here in spite of repeated efforts.”

He goes on to mention that a Hindu Sabha had been started in Sambhal around 1919 or 1920 — it was a “local affair” that had little to do with any similar all-India or provincial organisation. But the activities of this Sabha have “considerably irritated the Muslims,” Nehru notes, describing the activities as chiefly including litigation to recover temple properties and negotiating the boundaries of a graveyard.

Casteism, too, was alive and practiced — Nehru observes that the members of the “Chamar” caste were not allowed to use most wells in the town. When someone from the community drew water from a wall, Nehru notes that this upset both higher caste Hindus and Muslims, causing some resentment as it was done during the month of Ramzan.

Nehru sent Gandhi the report on 12 September 1924. On 17 September, Gandhi went on a fast for Hindu-Muslim unity, citing communal violence in Sambhal, Amethi, Kohat, and Gulbarga.

Gandhi’s fast over Sambhal lasted 21 days. As Nehru’s report shows, communal tensions in Sambhal have lasted since.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Details

Pilgrimage Sites in Sambhal

City of Kalki’: 41 pilgrimage sites & 19 wells ‘recovered’, admin eyes big Sambhal revamp

Kanwardeep.Singh@timesofindia.com

41 pilgrimage sites and 19 ancient wells have been "recovered."

Amarpati Kheda: An ASI-protected heritage site that includes Dadhichi Ashram and 21 samadhis, one of which is believed to be that of Prithviraj Chauhan's guru, Amarpati.

Sambhal currently has nine ASI-protected monuments.

Shankh Madhav Tirth:

Pap Mochan Tirth:

Bhadrika Ashram and Mrityunjay Mahatirth:

Importance:

Sambhal is believed to be the birthplace of Lord Kalki.

The sites hold religious and historical significance.

Population, violence: 1947-2011; 2024

August 29, 2025: The Times of India

Lucknow : A three-member judicial commission probing violence in Sambhal on Nov 24, 2024 has claimed in its report that the town has undergone a shift in demography since Independence, with the population of Hindus falling from 45% in 1947 to 1520% now due to “targeted violence, political complicity and resulting exodus”, according to sources, reports Pathikrit Chakraborty . In a chapter “History of Communal Violence in Sambhal”, part of the report, the panel claims the population breakup was 55% Muslim and 45% Hindu in the Sambhal municipal area, the sources said, adding that at present there are approximately 80-85% Muslims and 15-20% Hindus. Quoting 16 instances of communal violence between 1947 and 2019, the report claims there has been a pattern of appeasement in police action in the past to placate Muslims, sources said.

One money-lending caste among Hindus was especially targeted: Sambhal report

The panel members, led by retired Allahabad high court judge Devendra Kumar Arora and including retired IPS officer Arvind Kumar Jain and exIAS officer Amit Mohan Prasad, submitted their 450page report to UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath. The report is to be placed before the state cabinet and then in the assembly.

The report also claims one particular caste among Hindus was especially targeted as they would lend money to the other community.

The report claims they would be targeted so that money wouldn’t have to be repaid, and this fear triggered a large exodus among Hindus, the sources said. This led to a sharp decline in the Hindu population in the town, sources said, quoting the report. According to the 2011 Census, the population of the Sambhal municipal area (nagar palika parishad), then part of Moradabad district, was 2.2 lakh, comprising 1.7 lakh Muslims (77.6%) and 48.5 thousand Hindus (22%).

Principal secretary (home) Sanjay Prasad said, “The judicial commission constituted to probe the Sambhal incident has submitted its report to the CM.” He, however, refused to share details of the report. “We can say more only after studying it. Further action will be taken accordingly.”

In Nov 2024, violence in Sambhal during a courtmandated survey of the Jama Masjid to ascertain whether it was built over an ancient Harihar temple claimed the lives of four people. The commission was mandated to ascertain whether the violence in Sambhal was normal criminal activity or a planned conspiracy. It was also tasked to probe the role of local police and the action taken by them to bring the situation under control. The panel was also to make suggestions to prevent a recurrence of such an incident.

The report is said to have praised police action in the 2024 violence, acknowledging that strong police presence and govt intervention prevented large-scale violence. The crackdown, particularly around “Harihar Mandir”, thwarted rioters’ designs, it says, according to sources. Sources claimed the report singles out Samajwadi Party MP Zia-urRehman Barq’s allegedly incendiary speech at Jama Masjid on Nov 22 as the main trigger for the violence. It also mentions evidence of foreign involvement. Gang leader Shariq Satha, linked with Pakistan’s intelligence agency, allegedly ran a counterfeit currency racket and supplied weapons.

Several arms seized during the clashes bore “Made in USA” markings, suggesting international networks fuelling local unrest, the report claims. Traditional rivalry between Turks and converted Pathans was a secondary reason for the violence, it says. The panel members visited Sambhal four times, first on Dec 1, 2024, followed by visits on Jan 21, and Jan 30, 2025. The panel went there again on a two-day visit on Feb 28, spoke to witnesses, and urged those privy to events leading to the violence to depose before the commission.

Shiva temple

Rediscovered in 2024

Dec 15, 2024: The Times of India

From: Dec 15, 2024: The Times of India

Bareilly : An “ancient” Shiva temple was discovered in a locked house, abandoned by its Hindu occupants after the 1978 riots, in Shahi Jama Masjid area of Mahmood Khan Sarai, Sambhal district, during an anti-encroachment drive on Saturday. The house had allegedly been encroached upon for decades, and officials have now launched an investigation into its ownership, reports Kanwardeep Singh.

The temple was discovered during a large-scale campaign against encroachment and electricity theft. Vishnu Sharan Rastogi, patron of Nagar Hindu Sabha, alerted officials about its presence. Right-wing activists visited the site and offered prayers after the discovery. ASP Shrish Chandra said, “The temple is being cleaned, and the ramp over the well has been removed. The ASI has been asked to conduct carbon dating to determine the temple’s antiquity. Investigations found that some people had occupied the temple and built houses over it. Hindu families who lived here left for some reason, and the house remained closed since then. The temple contains statues of Lord Shiva and Hanuman. It will be handed over to its rightful owners, and action will be taken against the encroachers.”

Sambhal DM Rajender Pensiyasaid, “An investigation is underway regarding ownership of the house.”

Details

Dec 15, 2024: The Times of India

Sambhal : Three damaged idols were found inside the well of Bhasma Shankar temple in Sambhal that was reopened last week after being shut for 46 years, officials said.

The temple was reopened on Dec13 after authorities said they stumbled upon the covered structure during an anti-encroachment drive. The temple housed an idol of Lord Hanuman and a Shivling. It had remained locked since 1978. The temple also has a well nearby which the authorities had planned to reopen. District magistrate Rajender Pensiya said the ancient temple and the well are being excavated.

“Around 10-12 feet of digging has been done. During this, today, first an idol of Parvati was found with its head broken. Then Ganesh and Lakshmi idols were found,” he said. Asked if the idols were damaged and then put inside, Pensiya said, “All this is a matter of investigation.”

To a question on encroach- ments around the temple, he said some people removed encroachments on their own while others were requested to remove them. Further due process will be followed and then these will be removed through nagar palika, he said. On whether the temple will also be beautified, Pensiya said, “First the temple’s ‘prachinta’ (ancientry) will be ensured.”

SDM Vandana Mishra told PTI that information was received through local SHO that idols were found. The temple is situated in Khaggu Sarai area, just over a kilometre from Shahi Jama Masjid where violence took place on Nov 24 during a protest over a court-ordered survey of the mosque. The district administration has written to Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) for carbon dating of the temple, including the well. Carbon dating is a method used to determine the age of archaeological artefacts from ancient sites. PTI

Shahi Jama Masjid/‘Juma Masjid’

ASI restored its historic name

Kanwardeep Singh, April 9, 2025: The Times of India

Sambhal : Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) restored the “historic name” of the 16th-century Mughal-era Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal to ‘Juma Masjid’ and prepared a new blue signboard to replace the green one that stood outside the mosque for several decades. ASI officials said a sign would soon be installed to mark the site as a protected monument after a recent legal dispute and communal unrest.

A senior administrative official said, “The new blue board is not just a formal identification. It will also communicate to the people that this building is an ASI-protected monument. This step clarifies the historical identity and legal status of the site, which is now under ASI’s supervision.”

The monument was earlier marked with a green sign that read ‘Shahi jama masjid’. ASI’s lawyer Vishnu Kumar Sharma said, “The masjid is an ASI-protected structure. A few individuals allegedly removed the original ASI board and replaced it with a different one.” He added that the new sign was created using the name ‘Juma masjid’, which matches ASI’s “historical documentation”.

Advocate Tauseef Ahmad, representing the mosque committee, told TOI, “The meaning of Juma masjid and Jama masjid is the same. The ASI changed the colour of the board to blue from green, but it doesn’t matter as it will remain our place of worship.” The Shahi jama masjid, constructed in 1526 by Mir Hindu Beg, a noble under Mughal emperor Babur, is one of the oldest surviving Mughal-era monuments in India. ASI designated it as a protected site under the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act of 1904. Historical claims around the mosque’s origin have persisted for decades. An 1879 report by British archaeologist ACL Carlleyle recorded that Hindus believed the mosque was built atop the Shri Harihar Temple.

Tulsi Manas Temple

Holy potato/ 2025

March 11, 2025: The Times of India

Bareilly: A potato unearthed in a field near Kaima village in Bareilly on Sunday has been placed at Tulsi Manas Temple in Sambhal, where it now enjoys the sort of reverence usually reserved for ancient relics or deities, reports Kanwardeep Singh. The potato is said to bear the forms of four Vishnu nine avatars — a turtle, Sheshnaag, a fish, and a boar — leading to its swift ascension from agricultural curiosity to a religious artefact. By Monday, word spread, and the temple was drawing visitors at an impressive rate.