|

|

| (8 intermediate revisions by one user not shown) |

| Line 8: |

Line 8: |

| | See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div> | | See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div> |

| | |} | | |} |

| − | [[Category: Pakistan |L]] | + | [[Category: Pakistan |S]] |

| | [[Category: Places |L]] | | [[Category: Places |L]] |

| − | [[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | + | [[Category:Biography|S]] |

| | =Lahore= | | =Lahore= |

| | ==Lahore:== | | ==Lahore:== |

| Line 25: |

Line 25: |

| | [[File: Lahore1.PNG| Lahore |frame|500px]] | | [[File: Lahore1.PNG| Lahore |frame|500px]] |

| | [[File: Lahore2.PNG| Lahore |frame|500px]] | | [[File: Lahore2.PNG| Lahore |frame|500px]] |

| − |

| |

| | | | |

| | If our fetish for erecting ugly structures is anything to go by, our colonial heritage is at a risk of being eroded once and for all. The situation is grim and warrants immediate action from those who value the esthetically pleasing buildings that our colonial masters erected through the length and breadth of the country. | | If our fetish for erecting ugly structures is anything to go by, our colonial heritage is at a risk of being eroded once and for all. The situation is grim and warrants immediate action from those who value the esthetically pleasing buildings that our colonial masters erected through the length and breadth of the country. |

| Line 47: |

Line 46: |

| | As for their future writings, the creative couple have a plan. They now want to carry out research on post-colonial architecture. The task obviously is onerous but their first book testifies to the fact that they can do it too. | | As for their future writings, the creative couple have a plan. They now want to carry out research on post-colonial architecture. The task obviously is onerous but their first book testifies to the fact that they can do it too. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Lahore Scarred by development== | + | =See also= |

| − | | + | [[Lahore: A-E]] [[Lahore: F-K ]] [[Lahore: L-Q]] [[Lahore: R-Z ]] [[Lahore: architectural treasures]] [[Lahore: Civic issues ]] [[Lahore: History ]] [[Lahore: Parsi cusine ]] [[Lahore: Protected Monuments]] [[Bhai Ram Singh]] |

| − | The development spree in Lahore

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | By Shehar Bano Khan

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | [http://dawn.com/ Dawn]

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | [[File: Lahore Scarred by dev’t.PNG| Lahore Scarred by dev’t |frame|500px]] | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Lahore has sustained the ravages of invaders for ages. From the Mughals to the Sikhs down to the most recent history of the British rule, it has managed to write its own character and its own culture. Drawing support from its inhabitants, it struggled to develop into a distinct city, engaging conservatism to exist comfortably with intellectual freedom. All that was before Lahore was proselytised by the builders who robbed it of its essence, replacing ethos with plain old temporal consumerism. | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | The Lahore of today looks like a disgraceful city desperately trying to meet the architectural standards of the few whose introduction to finesse is summarily interrupted before the lesson can begin. The contemporary architecture of this historically and culturally vibrant city is making the conscious dwellers shake their heads in disapproval at the forceful new face being given to it. A nom de guerre for development, this new face embarrasses sensibilities and insults good taste.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | The developmental spree began with flyovers and underpasses which required the felling of trees, eliminating the hallmark green belts, some of which were planted before partition. Taking development a step further, it became imperative for the new city builders to turn residential boulevards into commercial avenues lined with tall, glazed monstrosities called plazas. Their rationale premised on the generation of revenue, pumping up a staid economy by carving a city profile structured to trade on the financial worthiness of land instead of wasting it to upkeep a stub from the past.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | “There’s nothing wrong in giving a new face to a city. The requirement of development is to change with time. That’s what our company is trying to do. We’re changing Lahore to suit the present. In another few years time it will be like New York and Dubai!” says an ambitious city builder.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | If New York and Dubai are the builders’ development criteria, Lahore just as might bid farewell to the bits and pieces of history left in its architectural expression. Kamil Khan Mumtaz, an architect cringes whenever he takes a walk around his residence on the Upper Mall.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | An unsightly and unnecessary underpass constructed near the Mian Mir Road, leading to the Jallo Park has depleted one side of the decades old green belt. The heavy traffic flow since the Dharampura underpass’ construction has reduced the number of people taking a leisurely walk down the canal flowing along this part of the city all the way to India.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | “I wonder how long this madness will continue,” comments Mumtaz. “Post modernism has made everything anti-beautiful. We are on an irreversible course to destruction. Architecture is a prime example of the destructive course we are following,” says he.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Once a city known for its magnificent gardens and the Mughal grandiose interpreted in architecture, Lahore is being steadily washed away by the cost-effective mindset introduced by the capitalist paradigm. “We’ve lost our hold on tradition, killing ourselves to impress. Architecture reflects our ego which is constantly seeking to impress others,” laments Mumtaz.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Some endangered historical sites, a structurally decrepit Walled City, and a few colonial style government buildings are all that is left of our heritage here. All these put together cannot compete with the concrete oddities quickly assembled as buildings. Pointing to an alley close to Noor Gulley in Rang Mahal, a shopkeeper of the area identifies to a missing archway of the old Mian Khan’s haveli.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | “Mian Khan’s haveli must be at least hundred years old. Now it no longer exists because the local land grabbing mafia stole the ancient bricks and sold them for huge profit. The people living in it were forced to settle elsewhere. It is not the only ancient place that has been sold off for profit. The entire Walled City is disappearing under the latest craze of building plazas and shops without a care for safety rules and how it can be kept warm and cool through construction,” discloses the shopkeeper.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Does that mean Lahore will soon cease to have an architectural history? Is the city’s claim to architectural evolution going to start with the Mughals and end on a colonial note? “It’s not as bad as that. I think we’re just evolving because after 30 years we’ve finally made the people realise that houses should be built according to our socio-cultural values,” says Wasif Ali Khan, an architect who like Nayyar Ali Dada revolutionised the old-style genre to give architecture its contemporary face.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Basing his architectural philosophy on socio-cultural patterns, Wasif Ali Khan argues that the utilisation of available materials, religious and vernacular, forms essential components of architecture. His use of bricks as available material and reverse plans for residential buildings, have made people realise the futility of expansive, colonial style mansions with long driveways leading to a house. “The goras imposed their style on us and took a lot of inspiration from the Mughals. But most of the time they could not decipher the Mughal architecture and decided to go for the simplistic style of columns supporting verandas overlooking huge lawns,” says Wasif Ali.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Dismissing plazas and ostentatious houses as expressions of popular culture, what to talk of structures built to conserve energy, he believes their demise over a period of few years will force the city builders to reconsider the necessity of seeking longevity, functional value and character in architecture. “These fad houses sustain only three to four years and are like cream toppings crumbling if exposed for too long to elements. They don’t have functional or aesthetic sustenance,” comments Wasif Ali Khan.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Easily divided into the pre-Mughal, Mughal, post-Mughal, a brief Sikh period, the colonial era and the present times, Khan believes that architecture is finally coming of age to weave its own pattern. “We’ve suffered the birth pains of this profession. When I graduated from the NCA (National College of Arts) in 1974, people were cautious about trusting a person who would draw lines on a piece of paper and call it a residential plan. They trusted the masons and the artisans who were directly involved in building a structure, than us,” says Wasif Ali.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Architectural study in Pakistan is but very young. In 1958, architecture as a short academic course was introduced for the first time in Pakistan. Among the first batch to graduate was Nayyar Ali Dada, now accredited with bringing renaissance in architecture to Pakistan. His structures were clear and stark, relying mostly on bringing out beauty in horizontal and vertical lines.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Commenting on Nayyar Ali’s style in his book, Modernity and Tradition, Kamil Khan Mumtaz writes: “… Nayyar Ali capitalised on sensitive design… The imposing external form of the Alhamra Arts Council building on The Mall relies on a simple, single, dominant element…..” The Open Air Theatre in Lahore and the Gaddafi Stadium are other sites exemplifying Nayyar Ali’s genius. “Nayyar sahib is the most revolutionary architect who took architecture beyond the Ayub era,” states Wasif Ali Khan.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | But even Nayyar Ali Dada’s architectural revolution has been somewhat short-lived. The builders of the ‘new’ Lahore are not interested in authenticating style with culture. Wasif Ali Khan’s optimism in Lahore’s architecture ‘weaving its own pattern’ ends at residential plans and Kamil Khan Mumtaz’s ‘modern paradigm’ takes over. “We are overawed by the West’s success. Imperialism, empirical science and technology are all part of our value system operating to achieve modernity. Look around and you’ll see that not just our country but the entire globe is on a destructive course from where there’s no turning back,” cautions Kamil Khan Mumtaz.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | ==Lahore Tollington==

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | April 30, 2006

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | EXCERPTS: If these walls could talk

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | [http://dawn.com/ Dawn]

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | [[File: Lahore Tollington.PNG| Lahore Tollington |frame|500px]] | + | |

| − | [[File: Lahore Tollington1.PNG| Lahore Tollington |frame|500px]] | + | |

| − | [[File: Lahore Tollington2.PNG| Lahore Tollington |frame|500px]] | + | |

| − | [[File: Lahore Tollington3.PNG| Lahore Tollington |frame|500px]] | + | |

| − | [[File: Lahore Tollington4.PNG| Lahore Tollington |frame|500px]] | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Nukta Art is a bi-annual Pakistani art magazine

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Samina Shah writes about the revamping of Tollington Market as a museum for Lahore

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | IN living memory, the building often referred as “Tollington”, has been a provision market. In fact it has been the main market for a long time for household products, and since it stands close to the Punjab University, the National College of Arts (NCA), and a host of other educational institutions, generations of students remember it with nostalgia.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | This edifice stands at the intersection of two axes, and the north to south alignment is from the old city of Lahore and the British cantonment, and the east to west is the old and new Anarkali bazar. Seen in the context of the colonial British policy for arts and industry, in 1864 the Tollington building was erected to house an exhibition of Indian crafts — an event that was immensely popular and continued for a period of nine months.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Looking at the chain of events as a sequel to this, the building housed antiquities and by the end of the 19th century it became the birth place of the Lahore Museum and later the NCA.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Meanwhile, during the First World War, Tollington fell into neglect. A few years later it found its fortunes turning when at the end of the war the British administration began to attend to civilian matters. Giving Tollington a new look in 1922, Sir Ganga Ram was given the charge for its restoration and repair work, and it was then that a flat one replaced the slanting wooden roof.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | However, for the curious student of architecture (and the general public), one interior wall of the present building has been deliberately left bare, that is, kept without plaster, to facilitate the observation of different stages of masonry and structure. The size of the brick varies as the walls go up, since in those days there was no concept of protection against dampness. But recently the restorers of this building have carefully made the entire walls damp-proof by working at the base of an already built-up formation.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | The building is in three sections: the main entrance hall, that is the waiting area, has benches of the same period and a fountain in the centre. The commercial building area, which used to have the fruit and vegetable market, has rows of open quarters as “one shop one craft” on both sides. Each room has a metal spiral staircase that goes up on the first floor of the same room as a loft for storage or book-keeping. The metal work is 19th century customised; the display boards outside each “shop” are ready as nameplates, described aptly in the novels of Somerset Maugham.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Proceeding with the renovation and restoration, Sajjad Kausar, the architect who has spared no pains in bringing this building to completion, says: “If the re-use of the building is close to the original, then the intervention is minimum, as making it better-looking or demolishing it is not restoration. In the building today, 1864 and 1922 have been cleverly combined.”

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | He is overly protective of his work, and so are his colleagues and advisors architects Nayyar Ali Dada and Kamil Khan Mumtaz — among others, who have closely followed its progress. “There is no place in Lahore for showcasing local crafts like the Covent gardens displays of the English crafts or the New Delhi State Emporium, which is a huge establishment for Indian crafts. The state ensures a price control, thus enabling the craftsmen to sell their products and attract tourists at the same time. I have restored this structure keeping in mind the need for a crafts bazar. There is a foyer in the centreand a Display Hall for two and three-dimensional exhibits. In short, I am looking at a Tollington Museum, which encompasses the above,” says Kausar.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Mumtaz adds that “this was an interesting case, as some of the issues faced were authenticity vs reconstruction for adaptive reuse, and because the intervention is to be minimal, restoration comes as the last choice. When we look at the patinas of history, questions like what to restore, and which period of history one restores it to, come up. These are all debatable issues, and should bring about more deliberations amongst professionals as such issues do not have readymade simple answers; they need brainstorming and discussions.”

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | This building is a landmark of Lahore and because it fell into an era of descent, the developers got involved and wanted to make it into a commercial venture. To do so they needed to demolish the structure, but later, after much protest, they changed their decision and were ready to re-make it into its original form. This brought the “Tajdeed-i-Lahore” at the helm of affairs along with the PHA, who have taken the “Tollington Market’ project as part of a larger scheme of conserving Lahore’s built heritage.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | “Conservation is not a sentimental journey, as cultural heritage is a document that has to be maintained in all honesty; if that is not followed scientifically then everything is reduced to fantasy,” reiterates Mumtaz. “The building is complete now; but what they plan to do with it is up to the administration.”

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Regarding the future of this building and its usage, the senior officials of the Lahore Museum and PHA are still deliberating and are unable to give any answer. However, some concerned citizens are enthusiastic for the establishment of a city museum.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | “What is needed is a museumologist to take the work on from here. This building can have sections like a hall of fame, Lahore’s history through the ages, the sacred sites, shrines, gardens, religious places like temples, gurdawaras, mosques, life styles, etc.,” says Faqir Saifuddin, the director of the Faqir Khana Museum. “I have given guidelines of how to go about it to the Governor of Punjab. Let us see what happens eventually,” he reflects.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | There are plans for developing the meat market area into an area of folk culture with the open spaces being utilised for folk music, puppetry, and the performing arts, thus making the Tollington Museum really come alive after more than a century of neglect and apathy.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − |

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Excerpted with permission from:

| + | |

| − | Nukta Art

| + | |

| − | Edited by Niilofur Farrukh Available from Flat # 104, 2nd floor, 11/C-9th Commercial Lane, Zamzama, Clifton, Karachi

| + | |

| − | Fax: 021-5845815

| + | |

| − | Email: nuktaart@yahoo.com

| + | |

| − | 142pp. Rs520

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − |

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Niilofur Farrukh is the author of Pioneering Perspectives, the first book on art by a Pakistani woman, as well as an art critic. She is on the advisory council of the Pakistan National Council of the Arts and is the president of AICA Pakistan — the Paris-based International Art Critics Association

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | Samina Shah is an art critic based in Lahore and freelances for various publications

| + | |

If our fetish for erecting ugly structures is anything to go by, our colonial heritage is at a risk of being eroded once and for all. The situation is grim and warrants immediate action from those who value the esthetically pleasing buildings that our colonial masters erected through the length and breadth of the country.

Lahore too has its share of colonial architecture, which has given it a peculiar look that simply dazzles the art buffs. But sadly the city, like so many other cities of Pakistan, is under threat as edifices of historical significance are being razed to the ground at a horrendous rate. The genie of crass commercialisation is playing havoc with the city’s illustrious architecture. At this juncture we must not only try to save our heritage but also offer due homage to the unsung heroes who played a mammoth role in evolving indigenous architecture for Lahore.

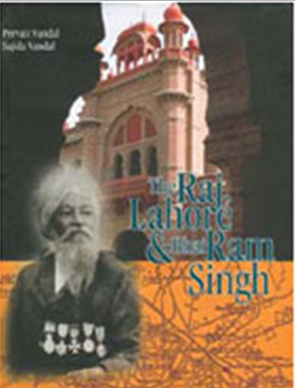

Bhai Ram Singh was one such true son of the soil who went into oblivion. He should have been given due plaudits for his extraordinary work for Lahore. But that was not to be and his name today is alive only in the dust-laden archives. It goes to the credit of Prof Sajida Vandal and her husband Pervez Vandal for conducting an extensive research on his life. Their united efforts resulted in Lahore Raj and Bhai Ram Singh, which showers ample light on Bhai Ram Singh and his achievements.

At the very outset Pervez Vandal, a trained architect with vast teaching experience declares, “The purpose of writing this book is simple. We are teachers and architecture is our subject. What should be our architecture? This simple question perturbed us so we tried answering it through the book.” Elaborating his point of view further, he adds, “You know in Lahore one can see marks of Mughal, Sikh and British architecture. But the thing is we must only consider architecture that is relevant to our present times. But we are a product of our past so one cannot also fully ignore the past. Since the British period belongs to our immediate past, we must study it. So we studied British architecture and how it evolved over the years. It was here that we were introduced to Bhai Ram Singh.”

Prof Sajida Vandal, who recently retired as principal of the National College of Art (NCA), Lahore, is as passionate about their first book as her husband. “The book is not about Bhai Ram Singh alone. Its purpose is to illustrate the architecture of a period through the work of Bhai Ram Singh. The son of a mason from Amritsar, Bhai Ram Singh found his mentor in Lockwood Kipling, the first principal of the then Mayo School of Art [later renamed NCA]. Ram Singh was among his first batch of students. Later he rose to become the fourth principal of Mayo School of Art through sheer hard work and dedication. It was a pity that both Pakistan and India completely neglected Ram Singh as there was nothing written about him. So ours is a first attempt in the subcontinent as far as Ram Singh is concerned,” explains Prof Sajida Vandal.

Picking up the thread, Pervez Vandal states, “In the British era, there were two schools of thought vying with each other. The first group belonged to the Imperialists, who were of the view that the British must force their own architecture on the inhabitants. They did not want to trust the natives, for in their eyes the natives were simply uncivilised. The buildings constructed during this time are the Quaid-i-Azam Library, Administrative Staff College and a few others. While there was another group who could be called Revivalist, they wanted to incorporate the influences of the local ambience in their architecture too. The buildings which they erected include the GPO, Town Hall, High Court, etc. Though they did not take the native on board, they tried erecting buildings the natives could relate to.”

The first principal Lockwood Kipling turned out to be native-friendly. He trained his students to erect buildings as per the requirements of the subcontinent. Bhai Ram Singh was perhaps his most outstanding pupil who did wonders with his deft touch. It was the idea of Lockwood Kipling that the natives should be left to do their own thing as far as their architecture was concerned. The first building that they erected was the Mayo School of Art.

The amount of research that went into this book is quite obvious. “We began work on it in 2000 and it took us six years to complete the task. We travelled to Amritsar to meet Ram Singh’s family members who were a great help. We are happy to get good response from the readers. There is an offer from India to launch the book there also. Some people in Canada too wanted us to launch the book there,” Prof Sajida Vandal further adds. For Bhai Ram Singh, the building of the Mayo School of Art was just the start. He later honed his skills and erected many other buildings such as the Aitchison College, Lahore Museum, Punjab University Senate Hall, Govt College Quadrangle Hostel and even the Khalsa College, Amritsar.

When asked to comment on the present trends in architecture prevalent in Lahore, the couple seems alarmed. “The architect should design buildings for the people. They are the real judges. If the public can relate to your architecture, it is a good omen. We are suffering from an inferiority complex. Instead of taking into consideration our own ideas and traditions, we are introducing things like Spanish cottages or Swiss villas. It’s our distorted vision. In our country, we will have to build structures that cater to our needs. We have different climates as well as circumstances so we cannot blindly follow the western style of architecture,” the couple says fervidly.

As for their future writings, the creative couple have a plan. They now want to carry out research on post-colonial architecture. The task obviously is onerous but their first book testifies to the fact that they can do it too.