Caste census: India

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> Additional information ma...") |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | [ | + | |

| + | =History= | ||

| + | ==Caste in the 1931 census== | ||

| + | [https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/modi-govt-caste-census-exercise-1931-9974935/. Anjishnu Das, May 1, 2025: ''The Indian Express''] | ||

| + | |||

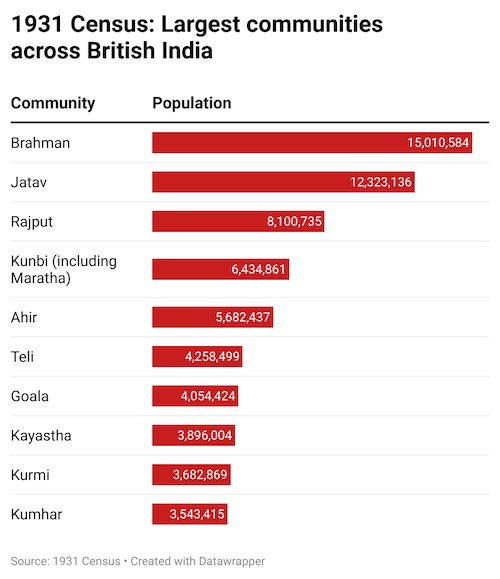

| + | [[File: 1931 census- Largest communities across British India.jpg|1931 census- Largest communities across British India <br/> From: [https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/modi-govt-caste-census-exercise-1931-9974935/. Anjishnu Das, May 1, 2025: ''The Indian Express'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

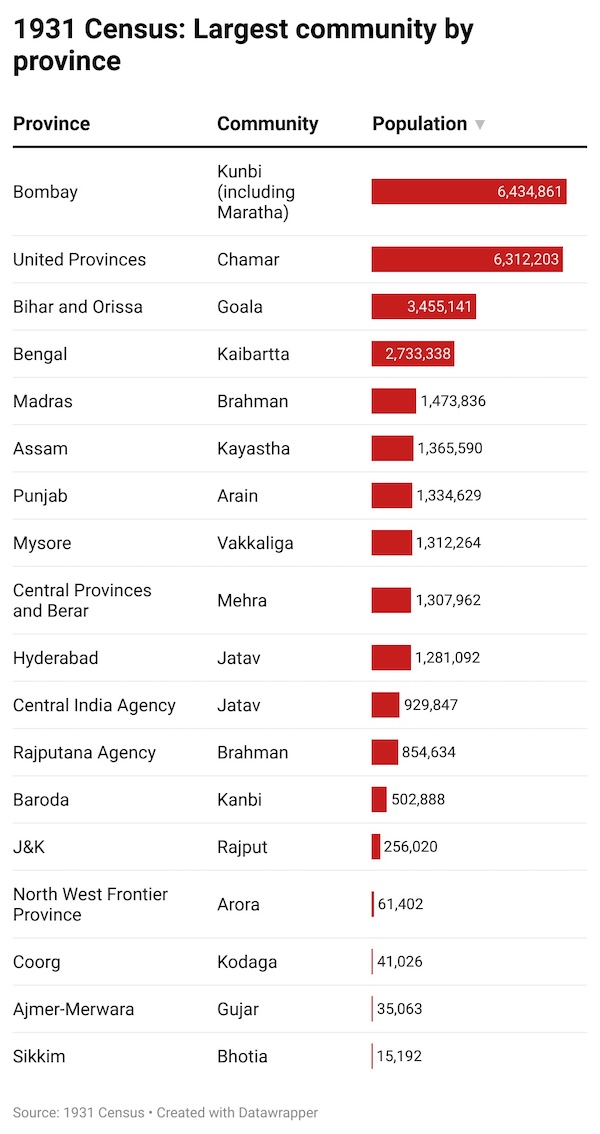

| + | [[File: 1931 census- Largest community by province.jpg|1931 census- Largest community by province <br/> From: [https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/modi-govt-caste-census-exercise-1931-9974935/. Anjishnu Das, May 1, 2025: ''The Indian Express'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Union Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (CCPA) on Wednesday decided that the forthcoming population Census will include caste enumeration, Union Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Opposition, led by the Congress, has been strongly pressing for a nationwide Caste Census for a long time, even as some states have come out with their own caste surveys. | ||

| + | Last September, the R S S too had indicated its support for a Caste Census, while adding that it should not be used for political or electoral purposes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Until Wednesday’s announcement, however, the ruling BJP had neither opposed the demand for a Caste Census openly, nor made any commitment to it. | ||

| + | While the then Congress-led UPA government had in 2011 initiated the Socio Economic and Caste Census (SECC), its specific data on caste was never released. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Before the SECC, the last time India conducted a Caste Census was in 1931. The nearly century-old exercise that last counted castes in a Census in India gives a good idea of the challenges the enumerators can face in any fresh effort, plus the complexities of the exercise. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 1931 Census that counted castes was conducted by the colonial British government, and was the first such exercise after the 1901 Census. The caste section put the numbers of Other Backward Classes (OBC) at 52% of the then total 271 million population of the country. This figure became the basis of the Mandal Commission’s recommendation in 1980 to grant 27% reservations to OBCs in education and government jobs, which was implemented only in 1990. | ||

| + | |||

| + | J H Hutton, the Census Commissioner at the time, countered those who argued against adding caste to the Census exercise saying that “the mere act of labelling persons belonging to a caste tends to perpetuate the system”. Hutton’s logic was that “it is impossible to get rid of any institution by ignoring its existence like the proverbial ostrich”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “It is difficult to see why the record of a fact that actually exists should tend to stabilise that existence,” Hutton wrote in the 1931 Census. “Caste is still of vital consideration in the structure of Indian society… It impinges in innumerable ways on questions not only of race and religion but also of economics, since it still goes far to determine the occupation, society and conjugaI life of every individual born into its sphere.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | But Hutton and his team ran into a series of problems while enumerating caste. Hutton enumerated some of them – from “a wave of non-cooperation, and the (salt) march of Mr Gandhi and his contrabandistas” to the Congress observing a “Census Boycott Sunday”, to numerous local-level movements that hampered efforts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Besides, over the course of previous Census exercises, the methodology on caste had undergone several changes. For instance, in 1881, only groups with more than a lakh population were counted. In 1901, Census Commissioner H H Risley decided to use the “varna hierarchy” system, sparking numerous movements by caste groups who viewed the Census as a vehicle to move up the social order. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the book “Caste, Politics, and the Raj”, historian Sekhar Bandyopahdyay writes that at the time, the Census was viewed not merely as a population count for each caste, but as a way “to fix the relative status of different castes and to deal with question of social superiority… (which) gave rise to a considerable agitation both at organised and unorganised levels”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | R B Bhagat, a professor at the International Institute for Population Sciences in Mumbai, wrote for the Economic and Political Weekly: “… Many lower caste people represented themselves as higher castes in order to raise their social status. In the Census, the underprivileged found an opportunity to express their aspiration and if possible to acquire new identity through enumeration”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hutton was openly critical of using the varna hierarchy in the Census. “All the subsequent Census officers in India must have cursed the day when it occurred to Risley … to attempt to draw up a list of caste according to their rank in the society. He failed, but the result of his attempt is as troublesome as if he has succeeded,” Hutton wrote. | ||

| + | |||

| + | So, in 1931, occupation rather than varna was used to classify castes. But this model had its own pitfalls. For one, it was unable to reconcile the variations in an occupational group’s social standing across regions – for instance, Hutton noted that “cultivation in northern India is a most respectable occupation, whereas in certain parts of southern India it is largely associated with the ‘exterior’ castes’”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “Admittedly this method… is far from being entirely satisfactory, since it can only recognise traditional occupation… and cannot simultaneously recognise more than one of several traditional occupations for the same caste,” Hutton wrote, but added that grouping castes roughly by occupation “also avoids any semblance of arrangement by order of social precedence”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While Hutton’s use of the occupational model addressed the question of defining caste, the 1931 Census still was unable to fully account for the fluidity of caste identity and the variations in the names of groups across regions, says Ayan Guha, a research fellow at the University of Sussex who has written on the history of caste. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The first problem was to define caste. You have to agree on the traits that make certain groups a caste and certain groups not a caste… The second problem was that caste has a lot of fluidity… The third problem was the standardisation of names – same castes with different names in different regions,” Guha says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Guha adds that Hutton had also flagged the problem of the dynamic nature of identity claims with groups changing caste identities from Census to Census. “A caste group that was Rajput in the last Census is now (in 1931) claiming to be Brahmin. This also happens at the provincial level – a particular caste group can claim different identities in different provinces,” he says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In fact, an official in Madras noted in the 1931 Census report, “Sorting for caste is really worthless unless nomenclature is sufficiently fixed to render the resulting totals close and reliable approximations. Had caste terminology the stability of religious returns, caste sorting might be worthwhile. With the fluidity of present appellations it is certainly not…” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Guha also points out “there was no uniform approach towards classification criteria for ordering of caste groups”. “It depended on provincial census commissioners and their subjective assessment,” he says, adding that if the objective for counting caste is affirmative action, “you need to agree upon clear criteria to ascertain the social position of caste groups, but such an agreement is likely to be elusive”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Guha says that if a Caste Census is to be conducted today, it is likely to run into the same issues as the 1931 Census. In particular, the fluidity of caste identity – from one group seeking to be identified as a tribe, like the Meiteis in Manipur, to some groups fusing over time, like herder communities coming together as Yadavs, to the fission of some castes – will likely pose a challenge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Those who are saying do (a Caste Census), they should think about how to do it. We already know how the colonial Census had issues with caste. That debate on the methodological dimensions of caste enumeration, its fluidity and the boundaries between groups is missing,” Guha says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Caste surveys of Bihar 2023; Telangana c.2023; Karnataka c.2015: findings== | ||

| + | [https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/caste-survey-bihar-telangana-karnataka-9975221/?ref=breaking_hp May 1, 2025: ''The Indian Express''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The BJP-led central government’s decision to include caste in the forthcoming Census comes in the wake of the caste surveys conducted by at least three states, which have also announced their intention to use the same for the policymaking purposes ahead. Two of these three states, Karnataka and Telangana, are ruled by the Congress, which has been at the forefront of seeking a caste census, while in the third one, Bihar, the Congress was a part of the then Nitish Kumar-led ruling coalition when the survey was carried out. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Bihar ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Bihar Assembly passed a unanimous resolution seeking a Caste Census across the country in February 2020, with Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, then heading a Mahagathbandhan government, putting his weight behind it. Despite the Centre dithering on the issue then, in Bihar even the BJP was part of the delegation that met Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2021 to seek a nationwide caste count. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Later, the Mahagathbandhan government went ahead to hold a statewide caste survey on its own. Its findings, released on October 2, 2023, showed that the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) together constituted more than 63% of the population of Bihar. | ||

| + | In absolute numbers, it put Bihar’s population at 13.07 crore, and put the OBCs at 3.54 crore (27%) and the EBCs at 4.7 crore (36%). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The “forward” castes or “General” category were found to make up 15.5% of the population, while the number of the SCs was estimated to be 20% and the Scheduled Tribes (STs) 1.6%. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The survey also showed that more than a third of Bihar’s families lived on around Rs 200 a day. Among the SCs, that number stands as high as 43.93%. The state is home to about 2.97 crore families, of which more than 94 lakh (34.13%) live on Rs 6,000 or less a month – the cut-off for below poverty line in Bihar. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The survey also pointed out how only 7% of the state’s population are graduates, again bringing into focus unemployment in the state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The BJP’s NDA allies from poll-bound Bihar lauded the Narendra Modi government’s announcement for caste enumeration as a “historic step” that would usher in a “more just society”.

| ||

| + | The JD(U), which is now with the NDA, pointed out that its president and CM Nitish Kumar created a “favourable ground for development” by carrying out a caste survey in the state. | ||

| + | JD(U) working president Sanjay Kumar Jha said the Centre’s decision would help make programmes for the deprived sections more focused. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas) president Chirag Paswan said it is an important decision in national interest, saying that his party had long called for it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Telangana ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Telangana Socio Economic, Educational, Employment, Political, and Caste survey report also pointed to high numbers of the Backward Classes (BCs). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The BCs make up 56.33% of Telangana’s population, according to the caste survey report. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The SCs and the STs account for 17.43% and 10.45% of the population respectively, according to the survey. Other Castes (OC) make up 15.79% of the population. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In absolute numbers, the BCs’ population in the state is 1,99,85,767, including 35,76,588 BC Muslims. The SC population is 61,84,319 and ST population is 37,05,929. The OC population in the state is 44,21,115. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Muslim population in the state, according to the survey, is 44,57,012 – about 12.56% of the population, including 10.08% BC Muslims and 2.48% OC Muslims. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The survey covered 3,54,77,554 people and 96.9% of the households in Telangana in a span of 50 days, state minister Uttam Kumar Reddy said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The caste survey was one of the promises made by the Congress for the 2023 Telangana Assembly elections. The party swept to power that year, defeating the incumbent Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The survey also came amidst a clamour for higher BC representation in politics. In the 2023 electins to the 119-member Telangana House, the BRS gave 22 tickets to BCs, while the Congress and the BJP gave 34 and 45 tickets to the community, respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The BCs are a voting bloc all the parties have been wooing because of their sheer population. The support of prominent BC groups such as Gouds, Munnuru Kapus and Yadavs to the Congress was said to have helped it defeat the BRS, which had been in power for 10 years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In his reaction to the Modi government’s decision to hold a Caste Census, Telangana CM Revanth Reddy said the Centre’s move “proved that what Telangana does today, India will follow tomorrow”. He also said it was a “proud moment” that Congress leader Rahul Gandhi’s “vision has become a policy even in Opposition”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Karnataka ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Karnataka caste survey report or the Socio-Economic and Education Survey was commissioned during CM Siddaramaiah’s first term in 2015. The report was however submitted to him only in his current term, on February 29 this year, which was not initially made public due to apprehensions within the Congress about possible adverse reactions from dominant communities such as Vokkaligas and Lingayats, who labeled the exercise “unscientific and outdated”. Even Deputy CM D K Shivakumar, a Vokkaliga, had opposed the release of the survey. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, with the Congress central leadership emphasising its commitment to social justice at the All India Congress Committee (AICC) session in Ahmedabad in early April — whose resolution highlighted a caste survey conducted in Telangana while calling for a national Caste Census — the survey report was finally tabled before the Siddaramaiah Cabinet on April 11. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Karnataka caste survey estimated the population of OBCs to be 69.6% – 38% more than existing estimates – and called for increasing their quota in the state from the existing 32% to 51%. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The population of Vokkaligas and Lingayats, who enjoy reservation under the III A and III B categories of OBC reservation, were found to be 12.2% and 13.6%, respectively. This is much less than their general population estimate of 17% and 15% respectively. The survey report has recommended a 4 percentage point increase in the quota under the II B category, paving the way for a 3 percentage point increase in reservation benefits for Vokkaligas and Lingayats. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While the report pays heed to the increased reservation demand of the OBC communities over the years, it has set off a worry. Some leaders feel that the political representation of various communities could take a hit going forward, especially at the time of ticket allocation, due to their population numbers presented by the survey. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the Congress, this is a tricky situation as it would not want to alienate these communities that have dominated Karnataka politics for decades now. Of its 136 MLAs in Karnataka, 37 are from the Lingayat community and 23 are Vokkaligas. The party had fielded as many as 51 Lingayat candidates in the 2022 Assembly polls. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another point from the survey that has ignited a row is its proposal for an increase in quota of 7 percentage points — from 15% to 22% — in the II A category that includes communities such as Kurubas to which CM Siddaramaiah belongs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The state Backward Commission, which has conducted the survey, has also recommended the creation of a new Most Backward Classes (MBC) category, called I B, to be carved out from the II A category. Communities such as Kurubas, who were earlier in II A, have reportedly been recommended for inclusion in the new category with a 12% quota. The II A category itself will have a reduced quota of 10%. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A senior Karnataka Congress leader said that Kurubas were being given “preferential treatment”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Amid the growing opposition to the survey, the Siddaramaiah Cabinet took up the report for discussion at its special meeting on April 17, but it remained inconclusive. The Cabinet will now meet on May 9 to further discuss the report and take a decision. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Welcoming the Centre’s decision to enumerate castes in the upcoming Census, Siddaramaiah Wednesday urged it to survey the social, economic and educational status of various communities while carrying out the exercise. He urged the Modi government to adopt the “Karnataka model” for the proposed Caste Census. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Andhra Pradesh ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The previous Andhra Pradesh government under Y S Jagan Mohan Reddy-led YSRCP had said that it would begin a comprehensive survey on January 19, 2024 to enumerate all castes in the state. It said it would “transform the living standards of people”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, when officials of the current Telugu Desam Party (TDP) were contacted, they said the YSRCP government’s “report never came out”. The YSRCP claimed that they could not make the report public as the Model Code of Conduct for the state’s Assembly and Lok Sabha polls had then come into force. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, TDP president and Andhra Pradesh CM Chandrababu Naidu had backed the Caste Census in an interview with The Indian Express. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Caste Census, yes, it has to be done. There is sentiment, and there is nothing wrong with it. You do a Caste Census, you do an economic analysis, and you go for a skill census. You work out how to build all these things and reduce economic disparities,” he had said. | ||

=A backgrounder= | =A backgrounder= | ||

| Line 52: | Line 184: | ||

In 2010, then Law Minister Veerappa Moily wrote to then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh calling for the collection of caste/community data in Census 2011. On March 1, 2011, during a short-duration discussion in Lok Sabha, Home Minister P Chidambaram spoke of several “vexed questions”: “There is a Central list of OBCs and State-specific list of OBCs. Some States do not have a list of OBCs; some States have a list of OBCs and a sub-set called Most Backward Classes. | In 2010, then Law Minister Veerappa Moily wrote to then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh calling for the collection of caste/community data in Census 2011. On March 1, 2011, during a short-duration discussion in Lok Sabha, Home Minister P Chidambaram spoke of several “vexed questions”: “There is a Central list of OBCs and State-specific list of OBCs. Some States do not have a list of OBCs; some States have a list of OBCs and a sub-set called Most Backward Classes. | ||

| − | The Registrar General has also pointed out that there are certain open-ended categories in the lists such as orphans and destitute children. Names of some castes are found in both the list of Scheduled Castes and the list of OBCs. Scheduled Castes converted to Christianity or Islam are also treated differently in different States. The status of a | + | The Registrar General has also pointed out that there are certain open-ended categories in the lists such as orphans and destitute children. Names of some castes are found in both the list of Scheduled Castes and the list of OBCs. Scheduled Castes converted to Christianity or Islam are also treated differently in different States. The status of a migr ant from one State to another and the status of children of inter-caste marriage, in terms of caste classification, are also vexed questions.” |

''' What happened to the SECC data, then? ''' | ''' What happened to the SECC data, then? ''' | ||

| Line 65: | Line 197: | ||

The R S S has not made any statements on a caste census in a while now, but has opposed the idea earlier. On May 24, 2010, when the debate on the subject had peaked ahead of Census 2011, then R S S sar-karyawah Suresh Bhaiyaji Joshi had said in a statement from Nagpur: “We are not against registering categories, but we oppose registering castes.” He had said a caste-based census is against the idea of a casteless society envisaged by leaders like Babasaheb Ambedkar in the Constitution and will weaken ongoing efforts to create social harmony. | The R S S has not made any statements on a caste census in a while now, but has opposed the idea earlier. On May 24, 2010, when the debate on the subject had peaked ahead of Census 2011, then R S S sar-karyawah Suresh Bhaiyaji Joshi had said in a statement from Nagpur: “We are not against registering categories, but we oppose registering castes.” He had said a caste-based census is against the idea of a casteless society envisaged by leaders like Babasaheb Ambedkar in the Constitution and will weaken ongoing efforts to create social harmony. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Communities|C | ||

| + | CASTE CENSUS: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Demography|C | ||

| + | CASTE CENSUS: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|C | ||

| + | CASTE CENSUS: INDIA]] | ||

Latest revision as of 18:03, 26 June 2025

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] History

[edit] Caste in the 1931 census

Anjishnu Das, May 1, 2025: The Indian Express

From: Anjishnu Das, May 1, 2025: The Indian Express

From: Anjishnu Das, May 1, 2025: The Indian Express

The Union Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (CCPA) on Wednesday decided that the forthcoming population Census will include caste enumeration, Union Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said.

The Opposition, led by the Congress, has been strongly pressing for a nationwide Caste Census for a long time, even as some states have come out with their own caste surveys. Last September, the R S S too had indicated its support for a Caste Census, while adding that it should not be used for political or electoral purposes.

Until Wednesday’s announcement, however, the ruling BJP had neither opposed the demand for a Caste Census openly, nor made any commitment to it. While the then Congress-led UPA government had in 2011 initiated the Socio Economic and Caste Census (SECC), its specific data on caste was never released.

Before the SECC, the last time India conducted a Caste Census was in 1931. The nearly century-old exercise that last counted castes in a Census in India gives a good idea of the challenges the enumerators can face in any fresh effort, plus the complexities of the exercise.

The 1931 Census that counted castes was conducted by the colonial British government, and was the first such exercise after the 1901 Census. The caste section put the numbers of Other Backward Classes (OBC) at 52% of the then total 271 million population of the country. This figure became the basis of the Mandal Commission’s recommendation in 1980 to grant 27% reservations to OBCs in education and government jobs, which was implemented only in 1990.

J H Hutton, the Census Commissioner at the time, countered those who argued against adding caste to the Census exercise saying that “the mere act of labelling persons belonging to a caste tends to perpetuate the system”. Hutton’s logic was that “it is impossible to get rid of any institution by ignoring its existence like the proverbial ostrich”.

“It is difficult to see why the record of a fact that actually exists should tend to stabilise that existence,” Hutton wrote in the 1931 Census. “Caste is still of vital consideration in the structure of Indian society… It impinges in innumerable ways on questions not only of race and religion but also of economics, since it still goes far to determine the occupation, society and conjugaI life of every individual born into its sphere.”

But Hutton and his team ran into a series of problems while enumerating caste. Hutton enumerated some of them – from “a wave of non-cooperation, and the (salt) march of Mr Gandhi and his contrabandistas” to the Congress observing a “Census Boycott Sunday”, to numerous local-level movements that hampered efforts.

Besides, over the course of previous Census exercises, the methodology on caste had undergone several changes. For instance, in 1881, only groups with more than a lakh population were counted. In 1901, Census Commissioner H H Risley decided to use the “varna hierarchy” system, sparking numerous movements by caste groups who viewed the Census as a vehicle to move up the social order.

In the book “Caste, Politics, and the Raj”, historian Sekhar Bandyopahdyay writes that at the time, the Census was viewed not merely as a population count for each caste, but as a way “to fix the relative status of different castes and to deal with question of social superiority… (which) gave rise to a considerable agitation both at organised and unorganised levels”.

R B Bhagat, a professor at the International Institute for Population Sciences in Mumbai, wrote for the Economic and Political Weekly: “… Many lower caste people represented themselves as higher castes in order to raise their social status. In the Census, the underprivileged found an opportunity to express their aspiration and if possible to acquire new identity through enumeration”.

Hutton was openly critical of using the varna hierarchy in the Census. “All the subsequent Census officers in India must have cursed the day when it occurred to Risley … to attempt to draw up a list of caste according to their rank in the society. He failed, but the result of his attempt is as troublesome as if he has succeeded,” Hutton wrote.

So, in 1931, occupation rather than varna was used to classify castes. But this model had its own pitfalls. For one, it was unable to reconcile the variations in an occupational group’s social standing across regions – for instance, Hutton noted that “cultivation in northern India is a most respectable occupation, whereas in certain parts of southern India it is largely associated with the ‘exterior’ castes’”.

“Admittedly this method… is far from being entirely satisfactory, since it can only recognise traditional occupation… and cannot simultaneously recognise more than one of several traditional occupations for the same caste,” Hutton wrote, but added that grouping castes roughly by occupation “also avoids any semblance of arrangement by order of social precedence”.

While Hutton’s use of the occupational model addressed the question of defining caste, the 1931 Census still was unable to fully account for the fluidity of caste identity and the variations in the names of groups across regions, says Ayan Guha, a research fellow at the University of Sussex who has written on the history of caste.

“The first problem was to define caste. You have to agree on the traits that make certain groups a caste and certain groups not a caste… The second problem was that caste has a lot of fluidity… The third problem was the standardisation of names – same castes with different names in different regions,” Guha says.

Guha adds that Hutton had also flagged the problem of the dynamic nature of identity claims with groups changing caste identities from Census to Census. “A caste group that was Rajput in the last Census is now (in 1931) claiming to be Brahmin. This also happens at the provincial level – a particular caste group can claim different identities in different provinces,” he says.

In fact, an official in Madras noted in the 1931 Census report, “Sorting for caste is really worthless unless nomenclature is sufficiently fixed to render the resulting totals close and reliable approximations. Had caste terminology the stability of religious returns, caste sorting might be worthwhile. With the fluidity of present appellations it is certainly not…”

Guha also points out “there was no uniform approach towards classification criteria for ordering of caste groups”. “It depended on provincial census commissioners and their subjective assessment,” he says, adding that if the objective for counting caste is affirmative action, “you need to agree upon clear criteria to ascertain the social position of caste groups, but such an agreement is likely to be elusive”.

Guha says that if a Caste Census is to be conducted today, it is likely to run into the same issues as the 1931 Census. In particular, the fluidity of caste identity – from one group seeking to be identified as a tribe, like the Meiteis in Manipur, to some groups fusing over time, like herder communities coming together as Yadavs, to the fission of some castes – will likely pose a challenge.

“Those who are saying do (a Caste Census), they should think about how to do it. We already know how the colonial Census had issues with caste. That debate on the methodological dimensions of caste enumeration, its fluidity and the boundaries between groups is missing,” Guha says.

[edit] Caste surveys of Bihar 2023; Telangana c.2023; Karnataka c.2015: findings

May 1, 2025: The Indian Express

The BJP-led central government’s decision to include caste in the forthcoming Census comes in the wake of the caste surveys conducted by at least three states, which have also announced their intention to use the same for the policymaking purposes ahead. Two of these three states, Karnataka and Telangana, are ruled by the Congress, which has been at the forefront of seeking a caste census, while in the third one, Bihar, the Congress was a part of the then Nitish Kumar-led ruling coalition when the survey was carried out.

Bihar

The Bihar Assembly passed a unanimous resolution seeking a Caste Census across the country in February 2020, with Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, then heading a Mahagathbandhan government, putting his weight behind it. Despite the Centre dithering on the issue then, in Bihar even the BJP was part of the delegation that met Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2021 to seek a nationwide caste count.

Later, the Mahagathbandhan government went ahead to hold a statewide caste survey on its own. Its findings, released on October 2, 2023, showed that the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) together constituted more than 63% of the population of Bihar. In absolute numbers, it put Bihar’s population at 13.07 crore, and put the OBCs at 3.54 crore (27%) and the EBCs at 4.7 crore (36%).

The “forward” castes or “General” category were found to make up 15.5% of the population, while the number of the SCs was estimated to be 20% and the Scheduled Tribes (STs) 1.6%.

The survey also showed that more than a third of Bihar’s families lived on around Rs 200 a day. Among the SCs, that number stands as high as 43.93%. The state is home to about 2.97 crore families, of which more than 94 lakh (34.13%) live on Rs 6,000 or less a month – the cut-off for below poverty line in Bihar.

The survey also pointed out how only 7% of the state’s population are graduates, again bringing into focus unemployment in the state.

The BJP’s NDA allies from poll-bound Bihar lauded the Narendra Modi government’s announcement for caste enumeration as a “historic step” that would usher in a “more just society”. The JD(U), which is now with the NDA, pointed out that its president and CM Nitish Kumar created a “favourable ground for development” by carrying out a caste survey in the state. JD(U) working president Sanjay Kumar Jha said the Centre’s decision would help make programmes for the deprived sections more focused.

Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas) president Chirag Paswan said it is an important decision in national interest, saying that his party had long called for it.

Telangana

The Telangana Socio Economic, Educational, Employment, Political, and Caste survey report also pointed to high numbers of the Backward Classes (BCs).

The BCs make up 56.33% of Telangana’s population, according to the caste survey report.

The SCs and the STs account for 17.43% and 10.45% of the population respectively, according to the survey. Other Castes (OC) make up 15.79% of the population.

In absolute numbers, the BCs’ population in the state is 1,99,85,767, including 35,76,588 BC Muslims. The SC population is 61,84,319 and ST population is 37,05,929. The OC population in the state is 44,21,115.

The Muslim population in the state, according to the survey, is 44,57,012 – about 12.56% of the population, including 10.08% BC Muslims and 2.48% OC Muslims.

The survey covered 3,54,77,554 people and 96.9% of the households in Telangana in a span of 50 days, state minister Uttam Kumar Reddy said.

The caste survey was one of the promises made by the Congress for the 2023 Telangana Assembly elections. The party swept to power that year, defeating the incumbent Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS).

The survey also came amidst a clamour for higher BC representation in politics. In the 2023 electins to the 119-member Telangana House, the BRS gave 22 tickets to BCs, while the Congress and the BJP gave 34 and 45 tickets to the community, respectively.

The BCs are a voting bloc all the parties have been wooing because of their sheer population. The support of prominent BC groups such as Gouds, Munnuru Kapus and Yadavs to the Congress was said to have helped it defeat the BRS, which had been in power for 10 years.

In his reaction to the Modi government’s decision to hold a Caste Census, Telangana CM Revanth Reddy said the Centre’s move “proved that what Telangana does today, India will follow tomorrow”. He also said it was a “proud moment” that Congress leader Rahul Gandhi’s “vision has become a policy even in Opposition”.

Karnataka

The Karnataka caste survey report or the Socio-Economic and Education Survey was commissioned during CM Siddaramaiah’s first term in 2015. The report was however submitted to him only in his current term, on February 29 this year, which was not initially made public due to apprehensions within the Congress about possible adverse reactions from dominant communities such as Vokkaligas and Lingayats, who labeled the exercise “unscientific and outdated”. Even Deputy CM D K Shivakumar, a Vokkaliga, had opposed the release of the survey.

However, with the Congress central leadership emphasising its commitment to social justice at the All India Congress Committee (AICC) session in Ahmedabad in early April — whose resolution highlighted a caste survey conducted in Telangana while calling for a national Caste Census — the survey report was finally tabled before the Siddaramaiah Cabinet on April 11.

The Karnataka caste survey estimated the population of OBCs to be 69.6% – 38% more than existing estimates – and called for increasing their quota in the state from the existing 32% to 51%.

The population of Vokkaligas and Lingayats, who enjoy reservation under the III A and III B categories of OBC reservation, were found to be 12.2% and 13.6%, respectively. This is much less than their general population estimate of 17% and 15% respectively. The survey report has recommended a 4 percentage point increase in the quota under the II B category, paving the way for a 3 percentage point increase in reservation benefits for Vokkaligas and Lingayats.

While the report pays heed to the increased reservation demand of the OBC communities over the years, it has set off a worry. Some leaders feel that the political representation of various communities could take a hit going forward, especially at the time of ticket allocation, due to their population numbers presented by the survey.

For the Congress, this is a tricky situation as it would not want to alienate these communities that have dominated Karnataka politics for decades now. Of its 136 MLAs in Karnataka, 37 are from the Lingayat community and 23 are Vokkaligas. The party had fielded as many as 51 Lingayat candidates in the 2022 Assembly polls.

Another point from the survey that has ignited a row is its proposal for an increase in quota of 7 percentage points — from 15% to 22% — in the II A category that includes communities such as Kurubas to which CM Siddaramaiah belongs.

The state Backward Commission, which has conducted the survey, has also recommended the creation of a new Most Backward Classes (MBC) category, called I B, to be carved out from the II A category. Communities such as Kurubas, who were earlier in II A, have reportedly been recommended for inclusion in the new category with a 12% quota. The II A category itself will have a reduced quota of 10%.

A senior Karnataka Congress leader said that Kurubas were being given “preferential treatment”.

Amid the growing opposition to the survey, the Siddaramaiah Cabinet took up the report for discussion at its special meeting on April 17, but it remained inconclusive. The Cabinet will now meet on May 9 to further discuss the report and take a decision.

Welcoming the Centre’s decision to enumerate castes in the upcoming Census, Siddaramaiah Wednesday urged it to survey the social, economic and educational status of various communities while carrying out the exercise. He urged the Modi government to adopt the “Karnataka model” for the proposed Caste Census.

Andhra Pradesh

The previous Andhra Pradesh government under Y S Jagan Mohan Reddy-led YSRCP had said that it would begin a comprehensive survey on January 19, 2024 to enumerate all castes in the state. It said it would “transform the living standards of people”.

However, when officials of the current Telugu Desam Party (TDP) were contacted, they said the YSRCP government’s “report never came out”. The YSRCP claimed that they could not make the report public as the Model Code of Conduct for the state’s Assembly and Lok Sabha polls had then come into force.

However, TDP president and Andhra Pradesh CM Chandrababu Naidu had backed the Caste Census in an interview with The Indian Express.

“Caste Census, yes, it has to be done. There is sentiment, and there is nothing wrong with it. You do a Caste Census, you do an economic analysis, and you go for a skill census. You work out how to build all these things and reduce economic disparities,” he had said.

[edit] A backgrounder

Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

Every Census in independent India from 1951 to 2011 has published data on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, but not on other castes. Before that, every Census until 1931 had data on caste.

The Bihar government has released the results of its recently concluded survey of castes in the state, which reveals that Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) constitute more than 63% of the population of Bihar.

CM Nitish Kumar congratulated the entire team involved in the caste survey process and said: “Resolution on caste-based survey was passed in the Bihar legislature through consensus. Nine political parties had taken a call in the Bihar Assembly on the state government bearing expenses of the caste survey.

The survey has not only considered one’s caste but also one’s economic status, which would help us devise further policies and plans for the development of all classes.”

What kind of caste data is published in the Census?

Every Census in independent India from 1951 to 2011 has published data on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, but not on other castes. Before that, every Census until 1931 had data on caste.

However, in 1941, caste-based data was collected but not published. M W M Yeats, the then Census Commissioner, said a note: “There would have been no all India caste table… The time is past for this enormous and costly table as part of the central undertaking…” This was during World War II.

In the absence of such a census, there is no proper estimate for the population of OBCs, various groups within the OBCs, and others. The Mandal Commission estimated the OBC population at 52%, some other estimates have been based on National Sample Survey data, and political parties make their own estimates in states and Lok Sabha and Assembly seats during elections.

How often has the demand for a caste census been made?

It comes up before almost every Census, as records of debates and questions raised in Parliament show. The demand usually comes from among those belonging to Other Backward Classes (OBC) and other deprived sections, while sections from the upper castes oppose the idea.

This time, however, things have been quite different. With Census 2021 delayed several times, the Opposition parties have made the loudest cry for a caste census as they seem to have converged on “social justice” as their slogan and glue. Earlier this year, while campaigning in Karnataka, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi said the Narendra Modi government should reveal the data of the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) conducted under the UPA-II government. Moreover, he called for a caste census and for the removal of the 50% cap on SC/ST/OBC reservations.

What has been the current government’s stand?

In July 2021, Union Minister of State for Home Affairs Nityanand Rai said in response to a question in Lok Sabha: “The Government of India has decided as a matter of policy not to enumerate caste-wise population other than SCs and STs in Census.”

Before this statement, Nityanand Rai had told the Rajya Sabha in March 2021: “The Union of India after Independence, decided as a matter of policy not to enumerate caste-wise population other than SCs and STs.”

But on August 31, 2018, following a meeting chaired by then Home Minister Rajnath Singh that reviewed preparations for Census 2021, the Press Information Bureau stated in a statement: “It is also envisaged to collect data on OBC for the first time.”

When The Indian Express filed an RTI request asking for the minutes of the meeting, the Office of Registrar General of India (ORGI) responded: “Records of deliberations in ORGI prior to MHA (Ministry of Home Affairs) announcement on August 31, 2018, to collect data on OBC is not maintained. There was not issued any minutes of the meeting.”

Where did the UPA stand on this?

In 2010, then Law Minister Veerappa Moily wrote to then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh calling for the collection of caste/community data in Census 2011. On March 1, 2011, during a short-duration discussion in Lok Sabha, Home Minister P Chidambaram spoke of several “vexed questions”: “There is a Central list of OBCs and State-specific list of OBCs. Some States do not have a list of OBCs; some States have a list of OBCs and a sub-set called Most Backward Classes.

The Registrar General has also pointed out that there are certain open-ended categories in the lists such as orphans and destitute children. Names of some castes are found in both the list of Scheduled Castes and the list of OBCs. Scheduled Castes converted to Christianity or Islam are also treated differently in different States. The status of a migr ant from one State to another and the status of children of inter-caste marriage, in terms of caste classification, are also vexed questions.”

What happened to the SECC data, then?

With an approved cost of Rs 4,893.60 crore, the SECC was conducted by the Ministry of Rural Development in rural areas and the Ministry of Housing & Urban Poverty Alleviation in urban areas. The SECC data excluding caste data was finalised and published by the two ministries in 2016.

The raw caste data was handed over to the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, which formed an Expert Group under former NITI Aayog Vice-Chairperson Arvind Pangaria for classification and categorisation of data. It is not clear whether it submitted its report; no such report has been made public.

The report of a Parliamentary Committee on Rural Development presented to the Lok Sabha Speaker on August 31, 2016, noted about SECC: “The data has been examined and 98.87 per cent data on individuals’ caste and religion is error free. ORGI has noted the incidence of errors with respect to 1,34,77,030 individuals out of the total SECC population of 118,64,03,770. States have been advised to take corrective measures.”

What is the contrary view?

The R S S has not made any statements on a caste census in a while now, but has opposed the idea earlier. On May 24, 2010, when the debate on the subject had peaked ahead of Census 2011, then R S S sar-karyawah Suresh Bhaiyaji Joshi had said in a statement from Nagpur: “We are not against registering categories, but we oppose registering castes.” He had said a caste-based census is against the idea of a casteless society envisaged by leaders like Babasaheb Ambedkar in the Constitution and will weaken ongoing efforts to create social harmony.