|

|

| Line 123: |

Line 123: |

| | | | |

| | Even after 50 years, the Nanavati case continues to have a tremendous recall value among a public infamous for its short memory. The question that animated discussions in countless chai shops of Bombay at the time of the trial remains relevant till today - “What would you have done if you were in his shoes?” | | Even after 50 years, the Nanavati case continues to have a tremendous recall value among a public infamous for its short memory. The question that animated discussions in countless chai shops of Bombay at the time of the trial remains relevant till today - “What would you have done if you were in his shoes?” |

| − | =From the SC's judgement of the case=

| |

| − | Supreme Court of India

| |

| − |

| |

| − | PETITIONER:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | K. M. NANAVATI

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Vs.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | RESPONDENT:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | STATE OF MAHARASHTRA

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATE OF JUDGMENT:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | 24/11/1961

| |

| − |

| |

| − | BENCH:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | SUBBARAO, K.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | BENCH:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | SUBBARAO, K.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DAS, S.K.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DAYAL, RAGHUBAR

| |

| − |

| |

| − | CITATION:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | 1962 AIR 605 1962 SCR Supl. (1) 567

| |

| − | ACT:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Jury Trial-Charge-Misdirection-Reference by

| |

| − | Judge, if and when competent-Plea of General

| |

| − | Exception-Burden of proof-"Grave an sudden

| |

| − | provocation"-Test-Power of High Court in

| |

| − | reference-Code of Criminal Procedure(Act, 5 of

| |

| − | 1898), 88. 307, 410, 417, 418 (1), 423(2), 297,155

| |

| − | (1), 162-Indian Penal Code, 1860 (Act 45 of 1860),

| |

| − | 88. 302, 300, Exception I-Indian Evidence Act,

| |

| − | 1872 (1 of 1872), 8. 105.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | HEADNOTE:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Appellant Nanavati, a Naval Officer, was put

| |

| − | up on trial under ss. 302 and 304 Part I of the

| |

| − | Indian Penal Code for the alleged murder of his

| |

| − | wife's paramour. The prosecution case in substance

| |

| − | was that on the day of occurrence his wife Sylvia

| |

| − | confessed to him of her illicit intimacy with

| |

| − | Ahuja and the accused went to his ship, took from

| |

| − | its stores a revolver and cartridges on a false

| |

| − | pretext, loaded the same, went to Ahuja's flat,

| |

| − | entered his bed room and shot him dead. The

| |

| − | defence, inter alia, was that as his wife did not

| |

| − | tell him if Ahuja would marry her and take charge

| |

| − | of their children, he decided to go and settle the

| |

| − | matter with him. He drove his wife and children to

| |

| − | a cinema where he dropped them promising to pick

| |

| − | them up when the show ended at 6 p.m., drove to

| |

| − | the ship and took the revolver and the cartridges

| |

| − | on a false pretext intending to shoot himself.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Then he drove his car to Ahuja's office and not finding him

| |

| − | there, drove to his flat. After an altercation a

| |

| − | struggle ensued between the two and in course of

| |

| − | that struggle two shots went off accidentally and

| |

| − | hit Ahuja. Evidence, oral and documentary, was

| |

| − | adduced in the case including three letters

| |

| − | written by Sylvia to Ahuja. Evidence was also

| |

| − | given of an extra-judicial confession made by the

| |

| − | accused to prosecution witness 12 who deposed that

| |

| − | the accused when leaving the place of occurrence

| |

| − | told him that he had a quarrel with Ahuja as the

| |

| − | latter had 'connections' with his wife and

| |

| − | therefore he killed him. This witness also deposed

| |

| − | that he told P. W. 13, Duty Officer at the Police

| |

| − | Station, what the accused had told him. This

| |

| − | statement was not recorded by P. W. 13 and was

| |

| − | denied by him in his cross-examination. In his

| |

| − | statement to the investigation officer it was also

| |

| − | not recorded.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The jury returned a verdict of 'not

| |

| − | guilty' on both the charges by a majority of 8: 1.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The Sessions Judge disagreed with that verdict, as

| |

| − | in his view, no reasonable body of men could bring

| |

| − | that verdict on the evidence and referred the

| |

| − | matter to the High Court under s. 307 of the Code

| |

| − | of Criminal Procedure. The two Judges of the

| |

| − | Division Bench who heard the matter agreed in

| |

| − | holding that the appellant was guilty under s. 302

| |

| − | of the Indian Penal Code and sentenced him to

| |

| − | undergo rigorous imprisonment for life. One of

| |

| − | them held that there were misdirections in the

| |

| − | Sessions Judge's charge to the jury and on a

| |

| − | review of the evidence came to the conclusion that

| |

| − | the accused was guilty of murder and the verdict

| |

| − | of the jury was perverse. The other Judge based

| |

| − | his conclusion on the ground that no reasonable

| |

| − | body of persons could come to the conclusion that

| |

| − | jury had arrived at. On appeal to this Court by

| |

| − | special leave it was contended on behalf of the

| |

| − | appellant that under s. 307 of the Code of

| |

| − | Criminal Procedure it was incumbent on the High

| |

| − | Court to decide the competency of the reference on

| |

| − | a perusal of the order of reference itself since

| |

| − | it had no jurisdiction to go into the evidence for

| |

| − | that purpose, that the High Court was not

| |

| − | empowered by s. 307(3) of the Code to set aside

| |

| − | the verdict of the jury on the ground that there

| |

| − | were misdirections in the charge, that there were

| |

| − | no misdirections in the charge nor was the verdict

| |

| − | perverse and that since there was grave and sudden

| |

| − | provocation the offence committed if any, was not

| |

| − | murder but culpable homicide not amounting to

| |

| − | murder.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''Held, ''' that the connections were without

| |

| − | substance and the appeal must fail.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ''' Judged by ''' its historical background and

| |

| − | properly construed, s. 307 of the Code of Criminal

| |

| − | Procedure was meant to confer wider powers of

| |

| − | interference on the High Court than

| |

| − | in an appeal to safeguard against an erroneous

| |

| − | verdict of the jury. This special jurisdiction

| |

| − | conferred on the High Court by s. 307 of the Code

| |

| − | is essentially different from its appellate

| |

| − | jurisdiction under ss. 410 and 417 of the code, s.

| |

| − | 423(2) conferring no powers but only saving the

| |

| − | limitation under s. 418(1), namely, that an appeal

| |

| − | against an order of conviction or an acquittal in

| |

| − | a jury trial must be confined to matters of law.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The words "for the ends of justice" in s.

| |

| − | 307(1) of the Code, which indicate that the Judge

| |

| − | disagreeing with the verdict, must be of the

| |

| − | opinion that the verdict was one which no

| |

| − | reasonable body of men could reach on the

| |

| − | evidence, coupled with the words 'clearly of the

| |

| − | opinion' gave the Judge a wide and comprehensive

| |

| − | discretion to suit different situations. Where.

| |

| − | therefore, the Judge disagreed with the verdict

| |

| − | and recorded the grounds of his opinion, the

| |

| − | reference was competent, irrespective of the

| |

| − | question whether the Judge was right in so

| |

| − | differing from the jury or forming such an opinion

| |

| − | as to the verdict. There is nothing in s. 307(1)

| |

| − | of the Code that lends support to the contention

| |

| − | that though the Judge had complied with the

| |

| − | necessary conditions, the High Court should reject

| |

| − | the reference without going into the evidence if

| |

| − | the reasons given in the order of reference did

| |

| − | not sustain the view expressed by the Judge.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Section 307(3) of the Code by empowering the

| |

| − | High Court either to acquit or convict the accused

| |

| − | after considering the entire evidence, giving due

| |

| − | weight to the opinions of the Sessions Judge and

| |

| − | the jury, virtually conferred the functions both

| |

| − | of the jury and the Judge on it.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Where, therefore, misdirections vitiated the

| |

| − | verdict of the jury, the High Court had as much

| |

| − | the power to go into the entire evidence in

| |

| − | disregard of the verdict of the jury as it had

| |

| − | when there were no misdirections and interfere

| |

| − | with it if it was such as no reasonable body of

| |

| − | persons could have returned on the evidence. In

| |

| − | disposing of the reference, the High Court could

| |

| − | exercise any of the procedural powers conferred on

| |

| − | it by s. 423 or any other sections of the Code.

| |

| − | referred to.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A misdirection is something which the judge

| |

| − | in his charge tells the jury and is wrong or in a

| |

| − | wrong manner tending to mislead them. Even an omission to

| |

| − | mention matters which are essential to the

| |

| − | prosecution or the defence case in order to help

| |

| − | the jury to come to a correct verdict may also in

| |

| − | certain circumstances amount to a misdirection.

| |

| − | But in either case, every misdirection or non-

| |

| − | direction is not in itself sufficient to set aside

| |

| − | a verdict unless it can be said to have occasioned

| |

| − | a failure of justice.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | There is no conflict between the general

| |

| − | burden that lies on the prosecution in a criminal

| |

| − | case and the special burden imposed on the accused

| |

| − | under s. 105 of the Evidence Act where he pleads

| |

| − | any of the General Exceptions mentioned in the

| |

| − | Indian Penal Code. The presumption of innocence in

| |

| − | the favour of the accused continues all through

| |

| − | and the burden that lies on the prosecution to

| |

| − | prove his guilt, except where the statute provides

| |

| − | otherwise, never shifts. Even if the accused fails

| |

| − | to prove the Exception the prosecution has to

| |

| − | discharge its own burden and the evidence adduced,

| |

| − | although insufficient to establish the Exception,

| |

| − | may be sufficient to negative one or more of the

| |

| − | ingredients of the offence.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Consequently, where, as in the instant case,

| |

| − | the accused relied on the Exception embodied in s.

| |

| − | 80 of the Indian Penal Code and the Sessions Judge

| |

| − | omitted to point out to the jury the distinction

| |

| − | between the burden that lay on the prosecution and

| |

| − | that on the accused and explain the implications

| |

| − | of the terms 'lawful act', lawful manner',

| |

| − | 'unlawful means' and 'with proper care and

| |

| − | caution' occurring in that section and point out

| |

| − | their application to the facts of the case these

| |

| − | were serious misdirections that vitiated the

| |

| − | verdict of the jury.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Extra-judicial confession made by the accused

| |

| − | is a direct piece of evidence and the stringent

| |

| − | rule of approach to circumstantial evidence has no

| |

| − | application to it. Since in the instant case, the

| |

| − | Sessions Judge in summarising the circumstances

| |

| − | mixed up the confession with the circumstances

| |

| − | while directing the jury to apply the rule of

| |

| − | circumstantial evidence and it might well be that the jury applied that rule

| |

| − | to it, his charge was vitiated by the grave

| |

| − | misdirection that must effect that correctness of

| |

| − | the jury's verdict.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The question whether the omission to place

| |

| − | certain evidence before the jury amounts to a

| |

| − | misdirection has to be decided on the facts of

| |

| − | each case. Under s. 297 of the Code of Criminal

| |

| − | Procedure it is the duty of the Sessions Judge

| |

| − | after the evidence is closed and the counsel for

| |

| − | the accused and the prosecution have addressed the

| |

| − | jury, to sum up the evidence from the correct

| |

| − | perspective. The omission of the Judge in instant

| |

| − | case, therefore, to place the contents of the

| |

| − | letters written by the wife to her paramour which

| |

| − | in effect negatived the case made by the husband

| |

| − | and the wife in their deposition was a clear

| |

| − | misdirection. Although the letters were read to

| |

| − | jury by the counsel for the parties, that did not

| |

| − | absolve the judge from his clear duty in the

| |

| − | matter.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The commencement of investigation under s.

| |

| − | 156 (1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure in a

| |

| − | particular case, which is a question of fact, has

| |

| − | to be decided on the facts of the case,

| |

| − | irrespective of any irregularity committed by the

| |

| − | Police Officer in recording the first information

| |

| − | report under s. 154 of the Code.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Where investigation had in fact commenced, as

| |

| − | in the instant case, s. 162 of the Code was

| |

| − | immediately attracted. But the proviso to that

| |

| − | section did not permit the eliciting from a

| |

| − | prosecution witness in course of his cross-

| |

| − | examination of any statement that he might have

| |

| − | made to the investigation officer where such

| |

| − | statement was not used to contradict his evidence.

| |

| − | The proviso also had no application to-a oral

| |

| − | statement made during investigation and not

| |

| − | reduced to writing.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In the instant case, therefore, there could

| |

| − | be no doubt that the Sessions Judge acted

| |

| − | illegally in admitting the evidence of P. W. 13 to

| |

| − | contradict P. W. 12 in regard to the confession of

| |

| − | the accused and clearly misdirected himself in

| |

| − | placing the said evidence before the jury.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Exception 1 to s. 300 of the Indian Penal

| |

| − | Code could have no application to the case. The

| |

| − | test of "grave and sudden" provocation under the

| |

| − | Exception must be whether a reasonable person

| |

| − | belonging to the same class of society as the

| |

| − | accused, placed in a similar situation, would be

| |

| − | so provoked as to lose his self control. In India,

| |

| − | unlike in England, words and gestures may, under

| |

| − | certain circumstances cause grave and sudden

| |

| − | provocation so as to attract that Exception. The

| |

| − | mental background created by any previous act of

| |

| − | the victim can also be taken into consideration in judging

| |

| − | whether the subsequent act could cause grave and

| |

| − | sudden provocation, but the fatal blow should be

| |

| − | clearly traced to the influence of the passion

| |

| − | arising from that provocation and not after the

| |

| − | passion had cooled down by lapse of time or

| |

| − | otherwise, giving room and scope for premeditation

| |

| − | and calculation.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Semble: Whether a reasonable person in the

| |

| − | circumstances of a particular case

| |

| − | committed the offence under grave

| |

| − | and sudden provocation is a

| |

| − | question of fact for the jury to

| |

| − | decide.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ......

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Is there any standard of a reasonable man for the application of the doctrine of "grave and sudden" provocation ? No abstract standard of reasonableness can be laid down. What a reasonable man will do in certain circumstances depends upon the customs, manners, way of life, traditional values etc.; in short, the cultural, social and emotional background of the society to which an accused belongs. In our vast country there are social groups ranging from the lowest to the highest state of civilization. It is neither possible nor desirable to lay down any standard with precision : it is for the court to decide in each case, having regard to the relevant circumstances. It is not necessary in this case to ascertain whether a reasonable man placed in the position of the accused would have lost his self- control momentarily or even temporarily when his wife confessed to him of her illicit intimacy with another, for we are satisfied on the evidence that the accused regained his self-control and killed Ahuja deliberately.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The Indian law, relevant to the present enquiry, may be stated thus : (1) The test of "grave and sudden" provocation is whether a reasonable man, belonging to the same class of society as the accused, placed in the situation in which the accused was placed would be so provoked as to lose his self-control. (2) In India, words and gestures may also, under certain circumstances, cause grave and sudden provocation to an accused so as to bring his act within the first Exception to s. 300 of the Indian Penal Code. (3) The mental background created by the previous act of the victim may be taken into consideration in ascertaining whether the subsequent act caused grave and sudden provocation for committing the offence. (4) The fatal blow should be clearly traced to the influence of passion arising from that provocation and not after the passion had cooled down by lapse of time, or otherwise giving room and scope for premeditation and calculation.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Bearing these principles in mind, let us look at the facts of this case. When Sylvia confessed to her husband that she had illicit intimacy with Ahuja, the latter was not present. We will assume that he had momentarily lost his self-control. But if his version is true-for the purpose of this argument we shall accept that what he has said is true-it shows that he was only thinking of the future of his wife and children and also of asking for an explanation from Ahuja for his conduct. This attitude of the accused clearly indicates that he had not only regained his self-control, but on the other hand, was planning for the future. Then he drove his wife and children to a cinema, left them there, went to his ship, took a revolver on a false pretext, loaded it with six rounds, did some official business there, and drove his car to the office of Ahuja and then to his flat, went straight to the bed-room of Ahuja and shot him dead. Between 1-30 P.M., when he left his house, and 4-20 P.M., when the murder took place, three hours had elapsed, and therefore there was sufficient time for him to regain his self-control, even if he had not regained it earlier. On the other hand, his conduct clearly shows that the murder was a deliberate and calculated one. Even if any conversation took place between the accused and the deceased in the manner described by the accused-though we do not believe that-it does not affect the question, for the accused entered the bed-room of the deceased to shoot him. The mere fact that before the shooting the accused abused the deceased and the abuse provoked an equally abusive reply could not conceivably be a provocation for the murder. We, therefore, hold that the facts of the case do not attract the provisions of Exception 1 to s. 300 of the Indian Penal Code.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In the result, conviction of the accused under s. 302 of the Indian Penal Code and sentence of '''imprisonment for life passed on him by the High Court are correct, '''and there are absolutely no grounds for interference. The appeal stands dismissed.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Appeal dismissed.

| |

The jury in the Greater Bombay sessions court pronounced Nanavati as not guilty, with an 8–1 verdict. Hon'ble Mr. Justice Ratilal Bhaichand Mehta (the sessions judge) considered the acquittal as perverse and referred the case to the high court.

The prosecution argued that the jury had been misled by the presiding judge on four crucial points:

1. One, the onus of proving that it was an accident and not premeditated murder was on Nanavati.

2. Two, was Sylvia's confession the grave provocation for Nanavati, or any specific incident in Ahuja's bedroom or both.

3. Three, the judge wrongly told the jury that the provocation can also come from a third person.

4. And four, the jury was not instructed that Nanavati's defense had to be proved, to the extent that there is no reasonable doubt in the mind of a reasonable person.

The court accepted the arguments, dismissed the jury's verdict and the case was freshly heard in the high court

Supreme Court of India

On November 24, 1961, the Supreme Court of India upheld the conviction [excerpts below].

Nanavati spent 3 years in prison. Prem's sister Mamie Ahuja was persuaded to forgive Nanavati. She gave her assent for his pardon in writing. Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, then governor of Maharashtra, pardoned Nanavati.

After his release, Nanavati, his wife Sylvia and their 3 children emigrated to Canada and settled in Toronto. Nanavati died in 2003.

KM Nanavati v/s the State of Maharashtra is one of the sensational court cases to have been tried by the Bombay High Court. It left the whole nation in a tizzy as to whether the murder at the centre of the case was committed by Nanavati in the 'heat of the moment' or was it a 'premeditated move'.

The enigma of the case has drawn quite a few adaptations of the case into literary texts like Indira Sinha's The Death of Mr Love, Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children (a chapter) and now Akshay Kumar's Rutsom, on which the entire film is based.

1. Commander Kawas Maneksaw Nanavati, a Parsi by birth, was a part of the Indian Navy and had settled down with his English wife, Sylvia and their two sons and a daughter in Bombay.

2. Nanavati's frequent staying away on assignments had Sylvia falling in love with a friend of her husband, Prem Ahuja. She wanted to divorce her husband and marry her lover, but Prem didn't have the same intentions. This was proven by the many letters Sylvia wrote, and was brought forward as a part of her testimony later.

3. On April 27, 1959, when Nanavati came back from an assignment and found Sylvia quite distraught, he asked her the reason behind the same. Sylvia came clean about the affair and also voiced her doubt that Prem might not reciprocate her feelings by marrying her and accepting her children.

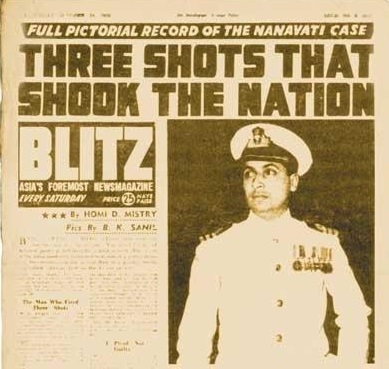

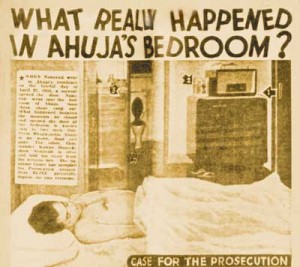

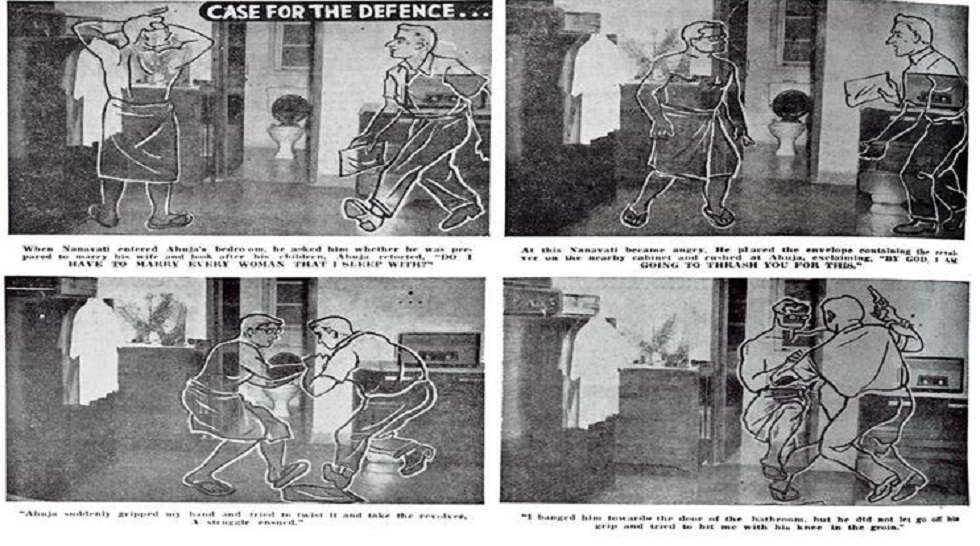

Meanwhile, Nanavati went to Prem's office and then to his flat. Once there, Nanavati asked Prem if he intended to marry Sylvia and accept their children. When Prem refused to take any responsibility for the affair, Nanavati shot him three times, killing him. Akshay Kumar's Rustom uses that as its tagline: '3 Shots That Shook The Nation'.

5. Nanavati turned himself in in front of the Deputy Commissioner of Police, after confessing his crime to the Provost Marshal of the Western Naval Command. It was in fact the Marshal who advised him to surrender himself.

6. Nanavati had the reputation of being a patriotic, morally upright officer of the Navy, who did not have any prior history of criminal charges. Prem had supposedly responded to Nanavati's question of marrying Sylvia and accepting her children with a "Should I marry every woman I sleep with?", before Nanavati shot him. Seeing a wronged husband in front of them, the jury sympathised with the accused and ruled in his favour, 8 to 1.

There were no witnesses in the Nanavati case. There were only two people in the room when the incident happened; one of whom was dead. It was practically Nanavati's word against the world's.

The victim's sister Mamie Ahuja and the prosecution contested the fact that what Nanavati had done was not because he lost his self-control after discovering the truth about his wife's affair. Their stance was that the murder was premeditated, and committed in cold blood. With this argument, the then-young lawyer Ram Jethmalani, assisting in the prosecution, appealed to the Bombay High Court.

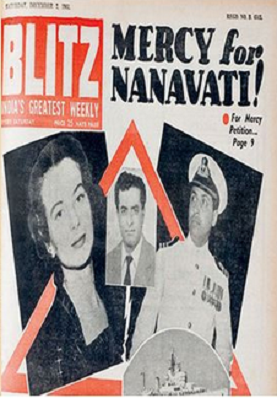

7. The Bombay High Court found Nanavati guilty and sentenced him to life imprisonment. He appealed the sentence in the Supreme Court, which upheld the decision of the High Court in November 1961. Meanwhile, a tabloid called Blitz was championing Nanavati's cause, and the case caught the public imagination in such a way that 25p copy sold for Rs 2 apiece.

8. This case led to some unrest between the Parsi and the Sindhi communities in Mumbai. While Nanavati belonged to the Parsi community, Ahuja was a Sindhi. Around the same time, Maharashtra Governor Vijaylakshmi Pandit (who was Jawaharlal Nehru's sister) received a mercy petition for Bhai Pratap, a prominent Sindhi businessman dealing in import-export of sports goods. Bureaucrats agreed that he could be pardoned. KM Nanavati walked in the same circles as the Gandhi-Nehru family, and thus found favour from the newly-appointed Governor.

9. Vijaylakshmi Pandit pounced on the chance and said that Bhai Pratap would be pardoned after Nanavati was pardoned. This would ensure that both the Parsi and Sindhi communities are happy. Ram Jethmalani's job was to convince the victim's sister, Mamie Ahuja.

10. Mamie Ahuja finally gave in to the Government's request, and KM Nanavati was released after spending three years in jail. Nanavati left for Canada with his wife and two children shortly after and was never heard of again. He passed away in 2003. Sylvia and their three children continue to survive him.

This is a story involving an extra-marital affair that resulted in a murder. The trial of the murderer generated unprecedented media coverage and the circumstances in which the murder took place resulted in huge public sympathy for him. This is also one of the first cases through which the maverick lawyer, Mr. Ram Jethmalani, came into the limelight for the first time.

Kamas Maneckshaw Nanavati was an Indian Naval Officer who had settled in Mumbai with his English wife, Sylvia, and their two children. As his work required him to be away from his family for long periods of time, his wife began an affair with his friend Prem Ahuja. Sylvia wanted to divorce Nanavati and marry Ahuja, but he refused. Distraught by the refusal, she spilled the beans about the affair to Nanavati when he returned to his family.

Nanavati was enraged, but he did not show it. He dropped Sylvia and their two children to a nearby cinema hall, proceeded to the Naval Docks from where he withdrew his pistol and six cartridges on an excuse, finished his shift and went to Ahuja’s office. He did not find him there. He proceeded to Ahuja’s flat and confronted him there asking whether he would marry Sylvia and take in his children.

He refused.

Nanavati shot him dead.

After committing the murder, he proceeded to the Provost Marshal of the Western Naval Command, where he confessed to his crime. The Provost Marshal asked him to surrender before the Deputy Commissioner of Police, which he did. Nanavati was an upright, moral and patriotic officer who did not have any prior history of criminal activity. The jury that heard his trial was sympathetic to his suffering and declared him to ‘not guilty’ by a majority of 8-1.

Ram Jethmalani, a young lawyer at the time, was assisting the prosecution on the request of Ahuja’s sister Mamie Ahuja. The trial court judge found this verdict to be perverse and referred the matter to the High Court.

Throughout the trial, the Bombay Daily Blitz, which folded shop in the 90s, championed the cause of Nanavati. One copy of the magazine, which was usually priced at 25 paisa, was selling at 2 rupees per issue at the height of the trial. The coverage of the trial pitted the Parsi and Sindhi communities in the city against each other. When the matter reached the High Court, a sentence of life imprisonment was read out, upon which Nanavati preferred an appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court confirmed the verdict of the High Court in November 1961. Blitz now went into an overdrive. It published a mercy petition in its pages, forcefully conveying the sentiments of the Parsi community which was wholly in favor of pardoning him. The rule of law and the demands of the society had clashed with each other. It was obvious that one had to bend in favor of the other.

Around the same time, Vijayalakshmi Pandit, newly appointed Governor of Bombay and sister of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, received a mercy petition from Bhai Pratap, a prominent Sindhi leader, in March 1962. Bhai Pratap had a business of import-export of sport goods and bureaucrats around her agreed that he could be pardoned. Pandit pounced on the chance. Bhai Pratap could be pardoned, she reasoned, after Nanavati had been pardoned. This way, both the Parsi and the Sindhi communities would get what they want. The proposal was conveyed to Jethmalani, who was asked to convince Mamie Ahuja for the same. She acceded to the government’s request.

Soon after being pardoned by the government, Nanavati left for Canada along with his wife and two children and was never heard of again. He died in 2003. Sylvia is still alive.

The case has inspired several Bollywood movies, plays and books including R K Nayar’s Ye Raaste Hain Pyaar Ke (1963) starring Sunil Dutt and Leela Naidu, and Indra Sinha’s book The Death of Mr Love (2002). And now, Akshay Kumar and Neeraj Pandey’s latest offing Rustom, is based on the case.

Even after 50 years, the Nanavati case continues to have a tremendous recall value among a public infamous for its short memory. The question that animated discussions in countless chai shops of Bombay at the time of the trial remains relevant till today - “What would you have done if you were in his shoes?”