Iran- India relations

(→2019) |

(→Muslims in India) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

=[[Chabahar]]= | =[[Chabahar]]= | ||

See [[Chabahar]] | See [[Chabahar]] | ||

| + | =Muslims in India= | ||

| + | ==2024== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=17_09_2024_001_010_cap_TOI Sep 17, 2024: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | New Delhi : The Centre “strongly deplored” remarks by Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei listing India alongside Gaza and Myanmar among regions where Muslims are “suffering”. Describing his comments as “misinformed and unacceptable”, the MEA stated, “Countries commenting on minorities in India are advised to look at their own record before making any observations about others.” | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Despite Iran’s strong ties with India, Khamenei had in the past too raised issues concerning Muslims in India, more specifically over the situation in Jammu & Kashmir after its special status was revoked in 2019. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Students from India in Iran= | ||

| + | ==As of 2025== | ||

| + | [https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-global/why-indian-kashmir-iran-10081970/ June 24, 2025: ''The Indian Express''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The ongoing Iran–Israel conflict, and the Indian government’s efforts to evacuate its citizens — especially medical students — from the region, has once again thrown the spotlight on a recurring question: Why do so many Indian students go abroad to study medicine? | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the MEA’s estimated data of Indian students studying abroad, in 2022, about 2,050 students were enrolled in Iran, mostly for medical studies, at institutions like the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University and Islamic Azad University. A significant number of the students are from Kashmir. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is not the first time a geopolitical crisis has exposed the scale of India’s outbound medical education. In 2022, during the Russia – Ukraine war, the Indian government had to evacuate thousands of medical students under ‘Operation Ganga’. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' A growing trend ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite a significant rise in the number of medical seats in India—from around 51,000 MBBS seats in 2014 to 1.18 lakh in 2024 —tens of thousands of students continue to pursue medical education abroad. The trend is visible in the rising number of candidates appearing for the Foreign Medical Graduate Examination (FMGE), which is mandatory for practising medicine in India after studying abroad. About 79,000 students appeared for the FMGE in 2024, up from 61,616 in 2023 and just over 52,000 in 2022. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This outward movement is driven by two main factors: competitiveness and cost. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “While the number of MBBS seats have increased in the country, the field continues to remain competitive. Students have to get a very good rank to get into government colleges,” said Dr Pawanindra Lal, former executive director of the National Board of Examinations in Medical Sciences, which conducts the FMGE. | ||

| + | |||

| + | More than 22.7 lakh candidates appeared for NEET-UG in 2024 for just over 1 lakh MBBS seats. Only around half of these seats are in government colleges. The rest are in private institutions, where costs can soar. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “A candidate ranked 50,000 can get admission in a good private college but the fees can run into crores. How many people in the country can afford that? It is just simple economics that pushes students towards pursuing medical education in other countries. They can get the degree at one-tenth the cost in some of the countries,” said Dr Lal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Why do so many Kashmiri students go to Iran? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | While affordability draws many Indian students abroad, Iran holds a unique appeal for those from the Kashmir Valley. For them, the choice is shaped not just by economics, but by cultural and historical ties. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Kashmir for a very long time has been called Iran-e-Sagheer or Iran Minor,” said Professor Syed Akhtar Hussain, a Persian scholar at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “The topography of Kashmir and the culture of Kashmir are similar to that of Iran. In the old times, they always thought Kashmir was a part of Iran in a way. In the 13th century, Meer Sayyed Ahmed Ali Hamadani came to Kashmir from Iran. He brought about 200 Syeds along with him, and those people brought crafts and industry from Iran to Kashmir. They brought carpet, papier-mâché, dry fruits and saffron too. Historically, this is the link” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Religious affinity is another driver. “Because there is a Shia element in Kashmir, and Shia presence in Iran, there is that affinity. Iran also feels happy that it has that special space in the heart of Kashmir,” he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most Kashmiri students pursue medical education in Tehran, while others study Islamic theology in the holy cities of Qom and Mashhad. According to Prof. Hussain, Iran has even created admission pathways tailored for Kashmiri students. “Iran gives some concessions to Kashmiri students to study there. By virtue of being Shia, they get admission very quickly and easily… for Kashmiris in Iran, it’s less expensive.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is often referred to as the “pargees quota”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''' What are the risks? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though admission is relatively easier and cheaper abroad, experts warn of important caveats in medical studies abroad. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “There are not a lot of eligibility requirements. If the student can pay, they usually get admission. Some universities run two batches for each year to accommodate more students,” said Dr Lal. However, he warned that some foreign universities operate two tiers of medical education: one designed to produce local doctors, and another primarily to award degrees to foreigners. “In fact, after completing some of the courses meant for foreigners, the students may not be eligible to practice in the host country,” he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To address this, India’s National Medical Commission (NMC) has introduced a rule stating that students will be eligible to practise in India only if they are also eligible to practise in the country where they studied. The NMC also mandates that the medical course be 54 months long, completed at a single university, followed by a one-year internship at the same institution. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dr Lal also flagged the lack of transparent information: “There are no foreign colleges or universities listed by the country’s medical education regulator that people can trust… The regulator should either provide a list of approved colleges or select, say, the top 100 colleges from a given country.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' What happens when such students return? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Even after securing their degree, foreign-trained doctors face several hurdles in India. Students from the Philippines, for instance, faced recognition issues because their courses were only 48 months long, short of the required 54. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another bottleneck is the FMGE, which all foreign-trained doctors must clear. The pass rate has historically been low: 25.8% in 2024, 16.65% in 2023, and 23.35% in 2022. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Even afterwards, they face challenges in getting employed. This is because their training is not as robust. Sometimes there is a lack of patients and practical training. The FMGE questions are simple, meant to test the students’ practical knowledge. And, yet, many are unable to pass the examination even after several attempts,” said Dr Lal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Economy-Industry-Resources|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | ||

| + | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Foreign Relations|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | ||

| + | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | ||

| + | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Iran|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | ||

| + | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

| + | |||

=YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS= | =YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS= | ||

=2014= | =2014= | ||

| Line 76: | Line 148: | ||

Amid growing bonhomie with Israel, India is hoping that Rouhani’s visit and also Modi’s own recent visit to Palestine will help dispel the notion that its West Asia policy is no longer on an even keel. For trade and investment, the two leaders recognised the need to put in place an effective banking channel. | Amid growing bonhomie with Israel, India is hoping that Rouhani’s visit and also Modi’s own recent visit to Palestine will help dispel the notion that its West Asia policy is no longer on an even keel. For trade and investment, the two leaders recognised the need to put in place an effective banking channel. | ||

| + | =See also= | ||

| + | [[Chabahar]] | ||

| + | [[Iran- India relations]] | ||

| Line 86: | Line 161: | ||

IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

[[Category:Iran|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | [[Category:Iran|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | ||

| + | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Economy-Industry-Resources|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | ||

| + | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Foreign Relations|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | ||

| + | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | ||

| + | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Iran|I IRAN- INDIA RELATIONSIRAN- INDIA RELATIONS | ||

IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | IRAN- INDIA RELATIONS]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:22, 6 July 2025

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] Chabahar

See Chabahar

[edit] Muslims in India

[edit] 2024

Sep 17, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi : The Centre “strongly deplored” remarks by Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei listing India alongside Gaza and Myanmar among regions where Muslims are “suffering”. Describing his comments as “misinformed and unacceptable”, the MEA stated, “Countries commenting on minorities in India are advised to look at their own record before making any observations about others.”

Despite Iran’s strong ties with India, Khamenei had in the past too raised issues concerning Muslims in India, more specifically over the situation in Jammu & Kashmir after its special status was revoked in 2019.

[edit] Students from India in Iran

[edit] As of 2025

June 24, 2025: The Indian Express

The ongoing Iran–Israel conflict, and the Indian government’s efforts to evacuate its citizens — especially medical students — from the region, has once again thrown the spotlight on a recurring question: Why do so many Indian students go abroad to study medicine?

According to the MEA’s estimated data of Indian students studying abroad, in 2022, about 2,050 students were enrolled in Iran, mostly for medical studies, at institutions like the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University and Islamic Azad University. A significant number of the students are from Kashmir.

This is not the first time a geopolitical crisis has exposed the scale of India’s outbound medical education. In 2022, during the Russia – Ukraine war, the Indian government had to evacuate thousands of medical students under ‘Operation Ganga’.

A growing trend

Despite a significant rise in the number of medical seats in India—from around 51,000 MBBS seats in 2014 to 1.18 lakh in 2024 —tens of thousands of students continue to pursue medical education abroad. The trend is visible in the rising number of candidates appearing for the Foreign Medical Graduate Examination (FMGE), which is mandatory for practising medicine in India after studying abroad. About 79,000 students appeared for the FMGE in 2024, up from 61,616 in 2023 and just over 52,000 in 2022.

This outward movement is driven by two main factors: competitiveness and cost.

“While the number of MBBS seats have increased in the country, the field continues to remain competitive. Students have to get a very good rank to get into government colleges,” said Dr Pawanindra Lal, former executive director of the National Board of Examinations in Medical Sciences, which conducts the FMGE.

More than 22.7 lakh candidates appeared for NEET-UG in 2024 for just over 1 lakh MBBS seats. Only around half of these seats are in government colleges. The rest are in private institutions, where costs can soar.

“A candidate ranked 50,000 can get admission in a good private college but the fees can run into crores. How many people in the country can afford that? It is just simple economics that pushes students towards pursuing medical education in other countries. They can get the degree at one-tenth the cost in some of the countries,” said Dr Lal.

Why do so many Kashmiri students go to Iran?

While affordability draws many Indian students abroad, Iran holds a unique appeal for those from the Kashmir Valley. For them, the choice is shaped not just by economics, but by cultural and historical ties.

“Kashmir for a very long time has been called Iran-e-Sagheer or Iran Minor,” said Professor Syed Akhtar Hussain, a Persian scholar at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “The topography of Kashmir and the culture of Kashmir are similar to that of Iran. In the old times, they always thought Kashmir was a part of Iran in a way. In the 13th century, Meer Sayyed Ahmed Ali Hamadani came to Kashmir from Iran. He brought about 200 Syeds along with him, and those people brought crafts and industry from Iran to Kashmir. They brought carpet, papier-mâché, dry fruits and saffron too. Historically, this is the link”

Religious affinity is another driver. “Because there is a Shia element in Kashmir, and Shia presence in Iran, there is that affinity. Iran also feels happy that it has that special space in the heart of Kashmir,” he said.

Most Kashmiri students pursue medical education in Tehran, while others study Islamic theology in the holy cities of Qom and Mashhad. According to Prof. Hussain, Iran has even created admission pathways tailored for Kashmiri students. “Iran gives some concessions to Kashmiri students to study there. By virtue of being Shia, they get admission very quickly and easily… for Kashmiris in Iran, it’s less expensive.”

This is often referred to as the “pargees quota”.

What are the risks?

Though admission is relatively easier and cheaper abroad, experts warn of important caveats in medical studies abroad.

“There are not a lot of eligibility requirements. If the student can pay, they usually get admission. Some universities run two batches for each year to accommodate more students,” said Dr Lal. However, he warned that some foreign universities operate two tiers of medical education: one designed to produce local doctors, and another primarily to award degrees to foreigners. “In fact, after completing some of the courses meant for foreigners, the students may not be eligible to practice in the host country,” he said.

To address this, India’s National Medical Commission (NMC) has introduced a rule stating that students will be eligible to practise in India only if they are also eligible to practise in the country where they studied. The NMC also mandates that the medical course be 54 months long, completed at a single university, followed by a one-year internship at the same institution.

Dr Lal also flagged the lack of transparent information: “There are no foreign colleges or universities listed by the country’s medical education regulator that people can trust… The regulator should either provide a list of approved colleges or select, say, the top 100 colleges from a given country.”

What happens when such students return?

Even after securing their degree, foreign-trained doctors face several hurdles in India. Students from the Philippines, for instance, faced recognition issues because their courses were only 48 months long, short of the required 54.

Another bottleneck is the FMGE, which all foreign-trained doctors must clear. The pass rate has historically been low: 25.8% in 2024, 16.65% in 2023, and 23.35% in 2022.

“Even afterwards, they face challenges in getting employed. This is because their training is not as robust. Sometimes there is a lack of patients and practical training. The FMGE questions are simple, meant to test the students’ practical knowledge. And, yet, many are unable to pass the examination even after several attempts,” said Dr Lal.

[edit] YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

[edit] 2014

[edit] Imposition of economic sanctions by the UNSC

The Times of India, Jul 20 2015

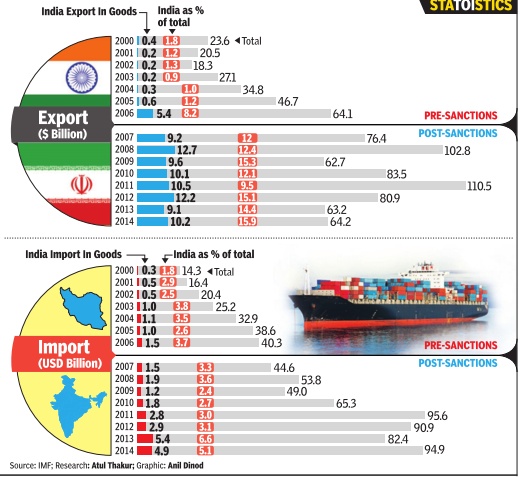

Following the report by the International Atomic Energy Agency regarding Iran’s noncompliance with safeguard agreements and Iran’s nuclear activities, the UNSC imposed a series of economic sanctions. The first of these sanctions were imposed in December 2006. An analysis of India’s trade with Iran shows a significant increase after these sanctions. Iran’s exports of goods to India were 1.8% of its total exports in 2000. This increased to 15.9% in 2014. In this period, Iran’s imports from India as a proportion of its total imports also increased from 1.8% to 5.1%.

[edit] 2018

[edit] Importance of Iran despite US sanctions

From: Indrani Bagchi, Iran will remain key to India’s foreign policy matrix, July 1, 2018: The Times of India

India can live without Iranian energy, but Tehran will remain a very important part of New Delhi’s foreign policy. As the US under Donald Trump takes an extreme view of sanctions against Iran, it may constrain India’s manoeuvring space significantly, if New Delhi is not careful.

Iran moved back into third place as a source for energy in 2016, soon after the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) unshackled global engagement with Tehran. But with the US openly calling for “zero” (oil imports) by November 4, things begin to look difficult. Notwithstanding the government’s brave words, Indian companies, banks, even oil PSUs, are scaling back.

During the earlier round of sanctions, India, like China and Japan, got a sanctions waiver because they “demonstrated” reductions (about 20% every 6 months). The trouble with buying Iranian oil in Indian currency remains the same — while Iran has tons of things it wants to buy from China, there’s very little it wants to buy from India beyond basmati rice and some pharmaceuticals. Post sanctions, the rupeerial deal has not yet taken off.

A bigger issue is connectivity. Energy may have dominated the last round of sanctions, but the focus is on multi-modal connectivity now. India needs Iran for a link to Central Asia and Russia. India wants to use the Chabahar port not only as an access point for Afghanistan, but also as athe International North-South Corridor (INSTC). India’s connectivity ambitions were made clear after it signed on to the TIR Convention and the Ashgabat Agreement on multi-modal transport.

Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari has promised to make Chabahar fully operational by 2018. But now that’s uncertain. The project is a win-win — it connects India but also provides a viable alternative to Pakistan as a route. Chabahar and INSTC is key to India’s geo-political ambitions of providing an alternative to China’s One Belt, One Road with a very different collaborative philosophy.

A carve-out for Chabahar was written into the US sanctions the last time round, as it was connected to Afghanistan. Logically, India could hope for a similar provision this time too. But Washington is seen as unpredictable these days. In addition, there has been virtually no high-level contact between the Modi government and key members of the Trump team in the past few months.

In the 1990s, India and Iran were on the same page regarding Afghanistan, when both countries supported the Northern Alliance against the Pak-Saudi supported Taliban. Now, Iran is on a different wavelength. Iran, like Russia, is more sympathetic to the Taliban, seeing them as a buffer against US presence and the growing footprint of IS. That has put a wedge with New Delhi. But as a friendly nation to the west of Pakistan, Iran remains invaluable to India.

India’s Iran woes have few sympathisers — not the US, and definitely not India’s closest partners in the Gulf and Middle East, all of whom have so far held their noses at New Delhi’s ties with Tehran. Israel and Saudi Arabia would lead the cheering squad if India has to scale back ties with Iran, as would the UAE.

India opposes terrorism as much as it opposes another country acquiring nuclear weapons in its neighbourhood. That puts India in a very different space, and much closer to the US. While India welcomed the JCPOA when it was signed in 2015, a decade prior, it had voted against Iran twice at the IAEA signalling its opposition to Tehran’s budding nuclear programme.

The question is no longer whether India can survive US sanctions. It can. But with its economy becoming more integrated with the world, does India want to subject itself to secondary sanctions from the US, specially with a vast private sector that would take the rap? The EU revived an older law that promises its companies compensation if they come under US sanctions. Despite this, energy biggies like Total and Shell have already pulled out from Iran.

India needs Iran for a link to Central Asia and Russia. India wants to use the Chabahar port not only as an access point for Afghanistan, but also to link it to the International North-South Corridor

[edit] Nine pacts deepen ties further

Nine pacts deepen Iran ties further, February 18, 2018: The Times of India

From: Nine pacts deepen Iran ties further, February 18, 2018: The Times of India

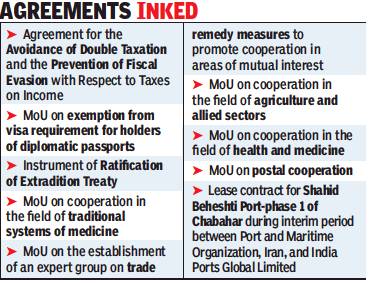

Iran may be faced with US sanctions but that did not come in the way of India looking to further ramp up its economic ties with Tehran with focus on connectivity, energy, trade and investment when PM Narendra Modi met Iranian President Hassan Rouhani here on Saturday. The two countries signed nine agreements, including a lease contract which will allow an Indian company to take over for 18 months operational control of facilities at Shahid Beheshti Port in Chabahar.

Thanking Rouhani for his contribution to the development of Chabahar port, Modi said India will support construction of the Chabahar-Zahedan rail link in Iran to allow Chabahar gateway’s potential to be fully utilised.

Port project a message to US that India is committed to Chabahar

We want to expand connectivity, cooperation in the energy sector and the centuries-old bilateral relationship, said Modi.

The port project is important for India as it will allow it to bypass Pakistan in accessing not just Afghanistan but also central Asian countries. The agreement is also a message to the US that India remains committed to Chabahar despite the US threat to tighten sanctions on Iran.

India and Iran also signed an agreement for avoidance of double taxation and prevention of fiscal evasion “with respect to taxes on income”.

Amid growing bonhomie with Israel, India is hoping that Rouhani’s visit and also Modi’s own recent visit to Palestine will help dispel the notion that its West Asia policy is no longer on an even keel. For trade and investment, the two leaders recognised the need to put in place an effective banking channel.

[edit] See also

Iran- India relations