Census and caste

(Created page with "{| Class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> </div> |} [[Category:Ind...") |

(→Should caste be enumerated?) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

[[Category:Demography |C ]] | [[Category:Demography |C ]] | ||

| − | =Should caste be enumerated?= | + | =The debate= |

| − | ==The | + | ==Should caste be enumerated?== |

| + | ===The Arguments=== | ||

[http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl1718/17180910.htm ASHA KRISHNAKUMAR, September 2-15, 2000: ''The Frontline''] | [http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl1718/17180910.htm ASHA KRISHNAKUMAR, September 2-15, 2000: ''The Frontline''] | ||

| Line 59: | Line 60: | ||

Among the various alternative methods of caste enumeration discussed at the seminar, the Andhra Pradesh experience, it was felt, was worth considering and replicating in other parts of the country. | Among the various alternative methods of caste enumeration discussed at the seminar, the Andhra Pradesh experience, it was felt, was worth considering and replicating in other parts of the country. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==1951-2025== | ||

| + | [https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/question-of-caste-in-free-india-1951-census-to-now-9995233/ SHYAMLAL YADAV, May 11, 2025: ''The Indian Express''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | On April 30 this year, the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (CCPA) approved caste enumeration in the forthcoming census. While India last collected caste data during the 1931 and 1941 Census, the latest available data is that of 1931 since the 1941 survey was not released. Similar data was collected during the 2011 Census too — but as a part of a special Socio Economic Caste Census (SECC) to identify households living below poverty line (BPL) as well as caste so that they could get various entitlements. Despite costing nearly Rs 5,000 crore, this countrywide report was never released. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a meeting of Census officials in February 1950, Deputy Prime Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, who also held the Home Affairs portfolio in the interim government headed by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, had announced categorically, “Formerly, there used to be elaborate caste tables which were required in India, partly, to satisfy the theory that it was a caste-ridden country and, partly, to meet the needs of administrative measures dependent upon caste division. In the forthcoming Census, this will no longer be a prominent feature.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hence, the 14 questions in the 1951 Census sought information on “nationality, religion and special groups”, among other information. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, the omission of caste in enumeration and tabulation would prove to be a huge loss for sociologists and anthropologists. As soon as the 1951 Census was completed, the government in January 1953 decided to constitute a commission headed by then Rajya Sabha MP, social reformer and journalist Dattatreya Balkrishna Kalelkar, popularly called Kaka Kalelkar, to look after the demand for reservation and other affirmative actions for the other backward classes (OBCs). | ||

| + | |||

| + | On March 18, 1953, then President Rajendra Prasad formally inaugurated the Kalelkar Commission. Speaking on the occasion, both President Prasad and Prime Minister Nehru expressed the hope that the “labours” of the commission would pave the way for a “classless” society in India. Nehru, who disliked the term “backward classes”, even remarked that it was wrong to label any section as backward, even if they were so, particularly, when 90% of the people in the country were poor and backward. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As the head of the First OBC Commission, Kalelkar’s biggest hurdle was the “lacunae” of caste data, especially of those who claimed to be OBCs. The Registrar General, meanwhile, provided the Commission with separate reports on the “estimated” population of certain OBC castes for different states. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the Registrar General’s estimates, nearly 11.5 crore Indians belonged to 930 backward castes. A report by the Kalelkar Commission noted that it had prepared a list of 2,399 castes as backward (Total population of the country in 1951 was 36.10 crore). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Stating that the Registrar General’s estimates had made its task “extremely difficult”, the Kalelkar Commission noted, “The Census Department has furnished us with approximate population figures for most of the communities, but we assume no responsibility for the reliability or finality of these figures.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Commission also got estimates from individual communities. However, the Commission added, “Figures furnished by the various communities were chiefly a matter of guesswork and their numbers were often exaggerated…. The caste-wise statistics in the previous Census reports (of 1941) were not compiled on a uniform basis throughout India and were, therefore, not of much use…We cannot consider this method of compilation either satisfactory or reliable, but we had to utilize whatever materials were made available to us.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Advising that the next Census should “give all the necessary information about castes and sub castes”, the Kalelkar Commission said, “We would like to record here that the Census of 1961 should collect and tabulate all the essential figures caste-wise. We are also of the opinion that if it is possible, this should be carried out in 1957 instead of in 1961, in view of the importance of the problems affecting backward classes.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Propagating for the caste census, the panel suggested, “It would certainly be valuable material for sociologists and anthropologists… But a lurking suspicion is asserting itself in my mind: Can we do it?” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though the report of the First OBC Commission, submitted in 1955, was never implemented, its suspicions would prove to be true. There was no caste census till 2011, which was just an SECC exercise and not a part of the 2011 Census. Kalelkar remained in the Rajya Sabha till 1964. Nehru, who constituted the Commission, passed away in May 1964. Till the end, his government was unclear on the final criteria for backwardness — caste or economics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Replying to a question in the Lok Sabha on April 17, 1963, on the criteria, Maragatham Chandrasekar, then Deputy Minister of Home Affairs, had said, “All that we are doing now is to suggest to the State Governments that they should adopt the economic criterion instead of the caste criteria.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | By 1977, the demand to implement the Kalelkar Commission report had gathered steam. The Morarji Desai government then constituted the Second OBC Commission, headed by Bindheshwari Prasad Mandal, the scion of the erstwhile Murho Estate in Bihar who also served as the seventh chief minister of the state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Mandal Commission’s report was submitted after Indira Gandhi stormed back to power in 1980. Its report, which too suggested a caste census, was implemented in parts in 1994 and then in 2009. Its suggestion on the caste census is finally expected to take place now. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Demography|C CENSUS AND CASTE | ||

| + | CENSUS AND CASTE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|C CENSUS AND CASTE | ||

| + | CENSUS AND CASTE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|CENSUS AND CASTE | ||

| + | CENSUS AND CASTE]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Why caste data of 2011 has not been released== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F09%2F01&entity=Ar00306&sk=9A5A2804&mode=text OBC data to be collected as part of Census in 2021, September 1, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

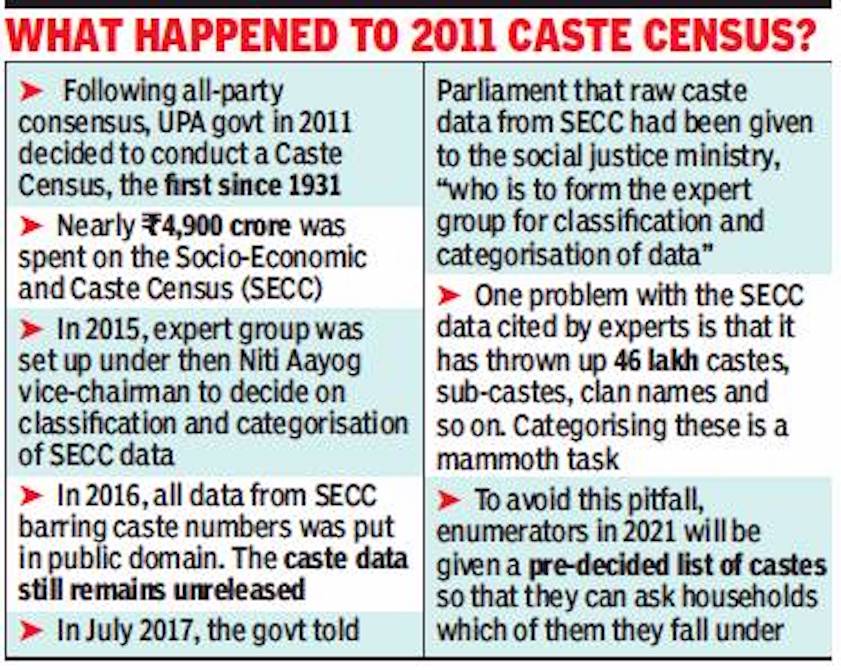

| + | [[File: Why the caste data collected in 2011 was not released.jpg|Why the caste data collected in 2011 was not released <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F09%2F01&entity=Ar00306&sk=9A5A2804&mode=text OBC data to be collected as part of Census in 2021, September 1, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Decision Marks Victory For OBC Lobby'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Modi government has decided to collect data on other backward classes (OBCs) as part of the 2021 Census in a decision which marks a concession to the demand of the assertive “backwards”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Friday’s decision could also potentially clear the way for sub-categorisation of castes lumped under the OBC rubric. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “It is envisaged to collect data on OBCs for the first time,” a home ministry release said soon after home minister Rajnath Singh chaired a meeting to take stock of preparations for Census 2021. This marks the end of policymakers’ squeamishness over restoring caste as an index in population enumeration. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Singh asked that improvements in design and technological interventions be made to ensure finalisation of Census data within three years of conducting the headcount. At present, this process can take as long as seven-eight years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Data on caste was last collected in 1931 Census''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The last time data on caste was collected as part of the decennial Census was in 1931. Although a socio-economic caste census (SECC) was conducted between 2011 and 2013 in deference to the demand of the powerful OBC lobby, it was part of the rural development ministry’s survey of socio-economic status of households. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The decision marks a victory for OBCs, who stridently campaigned for bringing caste back in the Census exercise. They maintain that they constitute more than 50% of the population and it was time this “reality” was acknowledged through the Census. There has, in fact, been much heartburn among the backward classes that the government has given a virtual go-by to the OBC enumeration done through the SECC. The OBC outfits have been complaining that the government did not form the committee to process the data that has been in its possession for the last three years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sources, however, said the SECC, which was purely a response-based exercise with respondents being asked to mention their castes, threw up a mountain of data which was full of anomalies. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While a reliable and accurate headcount of OBCs marks a victory for the “backwards” who have cornered the lion’s share of reservation in government jobs and educational institutions, what might take away their happiness is that this will happen in tandem with a simultaneous exercise to sub-categorise OBCs so as to identify the most backward classes among them that lag far behind the “creamy” layer in terms of ability and achievement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Demography|C | ||

| + | CENSUS AND CASTE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|C | ||

| + | CENSUS AND CASTE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|CENSUS AND CASTE]] | ||

Latest revision as of 05:45, 23 May 2025

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] The debate

[edit] Should caste be enumerated?

[edit] The Arguments

ASHA KRISHNAKUMAR, September 2-15, 2000: The Frontline

Suggestions of caste-based enumeration in the 2001 Census have provoked a serious debate.

CASTE-BASED enumeration of the population has not been carried out in India since 1931. In the last 70 years, some caste names have changed, quite a few new ones have emerged, several castes have merged with others or have moved up or down the social hie rarchy, and many have become politically active.

Caste being a sensitive issue, the proposition of caste-based census naturally provoked serious debate. Social scientists such as Marc Galanter have argued that the census recording of social precedence is a device of colonial domination, designed to und ermine as well as to disprove Indian nationhood. They contend that even assuming that caste data are relevant, enumeration of the population on the basis of caste is bound to be vitiated by vote-bank and reservation politics, leading to the inflation of population figures and the suppression or distortion of vital information on employment, education and economic status, among other things (Frontline, September 25, 1998). They hail the announcement of the Registrar-General of Census, J.K. Bantia, that castes would not be enumerated in the 2001 Census. The decision, according to those opposed to caste enumeration, reflects a clear commitment to eliminate inequality of status and invidious treatment and to establish a society in which the governme nt takes minimal account of ascriptive ties.

An argument in favour of caste enumeration is that if the complexity of castes, which have a significant bearing on society and the polity, is to be understood, authentic data on castes should be available. This was the general opinion of academics, poli ticians, government officials, representatives of various Backward Classes Commissions and mediapersons who gathered in Mysore in July for a seminar on "Caste Enumeration in the Census". The seminar, organised by the Madras Institute of Development Studi es (MIDS), Chennai, in collaboration with Mysore University, the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore, and the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore, also discussed alternative systems of data collection to obtain authentic inf ormation on castes.

The need to enumerate castes was emphasised by representatives of various Backward Classes Commissions. Their argument primarily centred on the problems of identification of B.Cs and providing reservation for them.

According to the Chairman of the Karnataka Backward Classes Commission, Prof. Ravivarma Kumar, the first National Commission on Backward Classes (appointed in 1953) and also the various State Commissions have recorded the difficulty they faced in impleme nting reservation for want of caste-related Census data. The Constitution, while providing for reservation in professional institutions and State services for the Scheduled Castes (S.Cs) and the Scheduled Tribes (S.Ts), which are known to be historically disadvantaged, has provisions in Article 15(4) (reservation in professional courses) and Article 16 (4) (reservation of jobs in state services) for reservation "for the advancement of socially and educationally backward classes of citizens, known as Oth er Backward Classes (OBCs), in proportion to their population". (However, the C in the OBC began to be referred to as denoting castes instead of "classes", which denotes a collection of individuals satisfying specified criteria.)

While Census enumerators continue to collect caste data of all castes and tribes listed in the Schedules to Articles 341 and 342, they do not collect data on OBCs. Hence, for want of data, the Backward Classes Commissions resort to indirect methods to ar rive at a head count of the OBCs, whose classification the judiciary most often invalidates.

On the recommendation of these commissions, the National Commission for Backward Classes Act, 1993, was enacted to revise the B.Cs list periodically for "the deletion of castes that have ceased to be backward classes or for inclusion in such lists new ba ckward classes". Again, this cannot be done without caste data.

J.K. Bantia defended the government's decision not to have caste enumeration during the head-count planned for 2001, saying: "The Census as it is is overloaded. Over five million tables are generated and analysed even without caste enumeration."

Andhra Pradesh Backward Classes Commission Chairman K.S. Puttaswamy built up a case for a well-designed, rigorous sample survey by an independent agency. He based his arguments on the path-breaking experiment of his Commission, which appointed T.V. Hanur av to conduct one of the largest independent statistical sample surveys in the country on the socio-economic and educational conditions of caste groups.

THE reasons which were laid out against enumerating castes in the Census broadly fell into three categories - moral, pragmatic and technical. A vigorous moral argument against the collection of caste data is that it would "increase casteism" , "legitimis e castes", "perpetuate castes" and "create cleavages in society". But most of the participants felt that these apprehensions were baseless as non-collection of caste data in the last 70 years had neither eliminated caste distinctions nor ended caste ineq uality.

A pragmatic argument was that there was a tendency to misreport and misrepresent data in order to garner benefits and privileges or to incite caste clashes. But then, non-collection of data has not helped reduce the frequency of caste clashes, which hav e become a reality especially in Bihar. Atrocities against Dalits occur with alarming frequency and intensity in many parts of the country. In fact, some experts argue that in order to address the issue of caste clashes there is a need for authentic data on the socio-economic and political conditions of caste groups.

In the absence of authentic caste data, either the 1931 figures are extrapolated with some modifications or estimates by caste groups themselves are relied upon. Either of these can be misleading, Puttaswamy says. For instance, the population of Andhra P radesh, according to the 1991 Census, was 6.65 crores and the Central Statistical Organisation's (CSO) estimation for 2001 is 7.69 crores. Almost all castes barring Kammas, Jains, Anglo-Indians and Buddhists have claimed B.C. status, arguing that they ar e the most backward on social, educational and economic grounds and that they are under-represented in government services and in political institutions. These castes have come out with estimations of their own numbers; the trouble is that only that they add up to 25 crores, or four times the State's actual population.

That the Census cannot enumerate castes for technical reasons, given the socio-economic complexities and political dimensions, was elaborated by Prof. K. Nagaraj of the MIDS and Prof. P.K. Misra and Suresh Patil of the Anthropological Survey of India. Ba sed on a statistical analysis of the size and spatial distribution of castes in the 1881 Census, Nagaraj argued that "there are broad dimensions to the caste structure which make it extremely difficult to capture the phenomenon of caste through a massive , one-time, quick operation like the Census." He said the complexity arose primarily because of the fragmentation, localisation, fluidity and ambiguity of castes.

Fragmentation: Of the 1,929 castes aggregated in the 1881 Census, 1,126 (58 per cent) had a population of less than 1,000; 556 (29 per cent) less than 100; and 275 (14 per cent) less than 10. There are a large number of single-member castes. At the other extreme, three caste groups - Brahmins, Kunbis and Chamars - accounted for more than a crore each. These three accounted for as many people as the bottom 1,848 (96 per cent) castes.

Localisation: Of the 1,929 caste groups, 1,432 (74 per cent) were found only in one locality (out of 17); 1,780 (92 per cent) were spread across four localities; and only two, Brahmins and the so-called Rajputs, had an all-India presence. The pattern of localisation also seemed to vary across space. For example, while the eastern and southern regions had high localisation of the big caste groups, in the northern and western regions they were spatially spread.

Thus there is a need for knowledge of the local caste systems. Even such statistical techniques as sampling would vary across space. "Decentralised data collection rather than a uniform all-India approach appears essential," Nagaraj said.

The Census, while aggregating caste groups across the country, predicates the exercise on 'varna' or on the caste-occupation nexus. This has resulted in disparate caste groups being clubbed together. If castes could not be grouped in 1881, it would be th at much more difficult to do so today because a number of changes have taken place in the caste system over the years.

Fluidity and ambiguity: Socio-economic and political changes, particularly those since Independence, have introduced a number of ambiguities in the structure and conception of castes, posing enormous problems in enumerating them through a Census-type pro cedure. For example, the changes in migration patterns and caste agglomerations, the caste-occupation nexus and the mix of sacral and secular dimensions in the nature of the caste groups vary widely across space and castes. This introduces ambiguities in the very perception of caste at various levels - legal, official, local and so on.

Misra and Suresh Patil argued that a centralised census operation was not the appropriate way to enumerate castes for several reasons, including change of nomenclature (for instance, Edagai and Balagai, two depressed communities in Karnataka, were entere d as Holeya and Madiga respectively until the 1921 Census, while they became Adi Karnataka and Adi Dravida in the 1931 Census); phonetic resemblance in names (for instance, the Gonds of Karnataka's Uttara Kannada district have nothing to do with the Gond tribals of Madhya Pradesh); religious movements and change of faith (the Veerasaiva religious movement in northern Karnataka drew many artisan castes such as the Kammara (blacksmith), Badiga (carpenter), Kumbara (potter) and Nekara (weaver) into its fol d, while not accepting some other artisan castes such as Bestha (fishermen), Machegara (cobbler) and Dhor (tanner), making it difficult to get separate figures for different artisan groups); and encroachment into another community's identity (the Nayaka community of Karnataka got into the S.T. list as there is a Nayaka tribe in Gujarat. Also its numbers swelled from 4,041 in 1931 to 1,37,410 in 1981).

There is thus the need for a decentralised, multi-disciplinary approach to caste enumeration involving all the stakeholders in the process. Thus the Census, which is centralised on several counts, is not the appropriate agency to enumerate something as complex as castes.

While Ravivarma Kumar argued that the Census could collect caste data by simply introducing a few parameters in the schedule, Prof V.K. Natraj of the MIDS said that it could at best give a head count of various caste groups but would not capture the soci o-economic and political complexities of caste in the country. A head count must be supplemented by an independent, decentralised study, which should then be made transparent, he said.

Among the various alternative methods of caste enumeration discussed at the seminar, the Andhra Pradesh experience, it was felt, was worth considering and replicating in other parts of the country.

[edit] 1951-2025

SHYAMLAL YADAV, May 11, 2025: The Indian Express

On April 30 this year, the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (CCPA) approved caste enumeration in the forthcoming census. While India last collected caste data during the 1931 and 1941 Census, the latest available data is that of 1931 since the 1941 survey was not released. Similar data was collected during the 2011 Census too — but as a part of a special Socio Economic Caste Census (SECC) to identify households living below poverty line (BPL) as well as caste so that they could get various entitlements. Despite costing nearly Rs 5,000 crore, this countrywide report was never released.

In a meeting of Census officials in February 1950, Deputy Prime Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, who also held the Home Affairs portfolio in the interim government headed by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, had announced categorically, “Formerly, there used to be elaborate caste tables which were required in India, partly, to satisfy the theory that it was a caste-ridden country and, partly, to meet the needs of administrative measures dependent upon caste division. In the forthcoming Census, this will no longer be a prominent feature.”

Hence, the 14 questions in the 1951 Census sought information on “nationality, religion and special groups”, among other information.

However, the omission of caste in enumeration and tabulation would prove to be a huge loss for sociologists and anthropologists. As soon as the 1951 Census was completed, the government in January 1953 decided to constitute a commission headed by then Rajya Sabha MP, social reformer and journalist Dattatreya Balkrishna Kalelkar, popularly called Kaka Kalelkar, to look after the demand for reservation and other affirmative actions for the other backward classes (OBCs).

On March 18, 1953, then President Rajendra Prasad formally inaugurated the Kalelkar Commission. Speaking on the occasion, both President Prasad and Prime Minister Nehru expressed the hope that the “labours” of the commission would pave the way for a “classless” society in India. Nehru, who disliked the term “backward classes”, even remarked that it was wrong to label any section as backward, even if they were so, particularly, when 90% of the people in the country were poor and backward.

As the head of the First OBC Commission, Kalelkar’s biggest hurdle was the “lacunae” of caste data, especially of those who claimed to be OBCs. The Registrar General, meanwhile, provided the Commission with separate reports on the “estimated” population of certain OBC castes for different states.

According to the Registrar General’s estimates, nearly 11.5 crore Indians belonged to 930 backward castes. A report by the Kalelkar Commission noted that it had prepared a list of 2,399 castes as backward (Total population of the country in 1951 was 36.10 crore).

Stating that the Registrar General’s estimates had made its task “extremely difficult”, the Kalelkar Commission noted, “The Census Department has furnished us with approximate population figures for most of the communities, but we assume no responsibility for the reliability or finality of these figures.”

The Commission also got estimates from individual communities. However, the Commission added, “Figures furnished by the various communities were chiefly a matter of guesswork and their numbers were often exaggerated…. The caste-wise statistics in the previous Census reports (of 1941) were not compiled on a uniform basis throughout India and were, therefore, not of much use…We cannot consider this method of compilation either satisfactory or reliable, but we had to utilize whatever materials were made available to us.”

Advising that the next Census should “give all the necessary information about castes and sub castes”, the Kalelkar Commission said, “We would like to record here that the Census of 1961 should collect and tabulate all the essential figures caste-wise. We are also of the opinion that if it is possible, this should be carried out in 1957 instead of in 1961, in view of the importance of the problems affecting backward classes.”

Propagating for the caste census, the panel suggested, “It would certainly be valuable material for sociologists and anthropologists… But a lurking suspicion is asserting itself in my mind: Can we do it?”

Though the report of the First OBC Commission, submitted in 1955, was never implemented, its suspicions would prove to be true. There was no caste census till 2011, which was just an SECC exercise and not a part of the 2011 Census. Kalelkar remained in the Rajya Sabha till 1964. Nehru, who constituted the Commission, passed away in May 1964. Till the end, his government was unclear on the final criteria for backwardness — caste or economics.

Replying to a question in the Lok Sabha on April 17, 1963, on the criteria, Maragatham Chandrasekar, then Deputy Minister of Home Affairs, had said, “All that we are doing now is to suggest to the State Governments that they should adopt the economic criterion instead of the caste criteria.”

By 1977, the demand to implement the Kalelkar Commission report had gathered steam. The Morarji Desai government then constituted the Second OBC Commission, headed by Bindheshwari Prasad Mandal, the scion of the erstwhile Murho Estate in Bihar who also served as the seventh chief minister of the state.

The Mandal Commission’s report was submitted after Indira Gandhi stormed back to power in 1980. Its report, which too suggested a caste census, was implemented in parts in 1994 and then in 2009. Its suggestion on the caste census is finally expected to take place now.

[edit] Why caste data of 2011 has not been released

OBC data to be collected as part of Census in 2021, September 1, 2018: The Times of India

From: OBC data to be collected as part of Census in 2021, September 1, 2018: The Times of India

Decision Marks Victory For OBC Lobby

The Modi government has decided to collect data on other backward classes (OBCs) as part of the 2021 Census in a decision which marks a concession to the demand of the assertive “backwards”.

Friday’s decision could also potentially clear the way for sub-categorisation of castes lumped under the OBC rubric.

“It is envisaged to collect data on OBCs for the first time,” a home ministry release said soon after home minister Rajnath Singh chaired a meeting to take stock of preparations for Census 2021. This marks the end of policymakers’ squeamishness over restoring caste as an index in population enumeration.

Singh asked that improvements in design and technological interventions be made to ensure finalisation of Census data within three years of conducting the headcount. At present, this process can take as long as seven-eight years.

Data on caste was last collected in 1931 Census

The last time data on caste was collected as part of the decennial Census was in 1931. Although a socio-economic caste census (SECC) was conducted between 2011 and 2013 in deference to the demand of the powerful OBC lobby, it was part of the rural development ministry’s survey of socio-economic status of households.

The decision marks a victory for OBCs, who stridently campaigned for bringing caste back in the Census exercise. They maintain that they constitute more than 50% of the population and it was time this “reality” was acknowledged through the Census. There has, in fact, been much heartburn among the backward classes that the government has given a virtual go-by to the OBC enumeration done through the SECC. The OBC outfits have been complaining that the government did not form the committee to process the data that has been in its possession for the last three years.

Sources, however, said the SECC, which was purely a response-based exercise with respondents being asked to mention their castes, threw up a mountain of data which was full of anomalies.

While a reliable and accurate headcount of OBCs marks a victory for the “backwards” who have cornered the lion’s share of reservation in government jobs and educational institutions, what might take away their happiness is that this will happen in tandem with a simultaneous exercise to sub-categorise OBCs so as to identify the most backward classes among them that lag far behind the “creamy” layer in terms of ability and achievement.