Kumari/ Taleju (living goddess): Nepal

(→Unscathed by the April 2015 earthquake) |

|||

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

Barring the chipping of some slabs at its base, Taleju Temple was not damaged. | Barring the chipping of some slabs at its base, Taleju Temple was not damaged. | ||

| + | =See also= | ||

| + | [[Kathmandu, 1908 ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Kathmandu: What the 2015 earthquake destroyed]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Kumari/ Taleju (living goddess): Nepal]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Nepal earthquake: 2015]] | ||

Revision as of 15:09, 6 May 2015

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The authors of this page are…

Vijay Jung Thapa, mainly

Most of this page has been adapted from Tryst with the gods, by Vijay Jung Thapa January 31, 1997 India Today

What is a Kumari

(A Kumari is somewhat like a divine Spanish Catholic virgin.)

Kumari is worshipped as Taleju (Tulja in India), a form of Durga. (Newars ruled the city states of Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, Patan and Kirtipur in the Kathmandu Valley until they were subjugated by the Gorkhas in the late 18th century). During Indrajatra, kings (now Nepal’s presidents) seek Kumari's blessings, touching her feet in public.

Bhaktapur and Patan have separate Kumaris. The Kathmandu Kumari is the most important.

The Taleju tradition

Taleju, the protective deity of Nepal, in one of its numerous forms, is menacing: the embodiment of all horrors of the mortal mind. According to legend, many centuries ago she befriended a Nepali king and would often come in the form of a stunningly attractive woman to play dice with him.

One day a princess interrupted them. Infuriated at being seen by another mortal, Taleju vanished. But after much pleading by the king she relented, and said she would guide him on the condition that he could no longer see her. From then on, Taleju's spirit is brought to life in the form of a virgin girl.

Michael Allen, an anthropologist who has studied the Kumaris, writes: "There is always the implication...that the king developed a strong desire to sexually possess the goddess." That's why, reasons Allen, the Kumaris are always virgins, a far cry from the saucy, dice-throwing Taleju of legend.

Yet, embodied in this tiny girl are all the supernatural powers of the dreaded Taleju. Udhav Karmacharya, the head priest of the huge Taleju temple in the late 1990s, where even today the king is not allowed entry, said: "All Kumaris have latent powers that manifest at any time." He recalled an incident when King Tribhuvan went in for his yearly blessing from the Kumari.

The girl, supposed to anoint the monarch's forehead with vermilion, instead tried to place it on the head of the young crown prince. Karmacharya's father, then head priest, had to literally force the girl's hand onto the king's forehead. It was a bad omen. Six months later, King Tribhuvan died and his son succeeded him.

The Kumari cult comes wrapped in numerous such tales. One of the Kumaris – who was born in and was Kumari in the 1930s - chipped a tooth. Three days later, a huge earthquake shook Kathmandu. Another,

Anita, fell violently sick in 1979, which was a time when the Shah monarchy was in crisis. The royal palace sent the king's physician, who could do little ([how could he] cure a goddess?).

A tantric was also summoned, but he died in the night before completing his incantations. Miraculously, she came around just as the threat to the king was diminishing. "The Kumari feels and experiences what the kingdom is going through," says Karmacharya. Superstition cuts both ways: it may help the kingdom, but it definitely hurts a former Kumari.

How the Kumaris are chosen

Nanimayya was four when her parents were informed that she was a Kumari candidate. All Kumaris are chosen from the Buddhist Sakya community of goldsmiths. A special council starts the search, guided by a list of 32 - sometimes bizarre - attributes: a neck like a conch shell; a voice like a running stream; cheeks like a lion; skin the colour of gold and soft as a duck's.

Once the candidates are shortlisted, the royal astrologer determines who is most compatible with the king. Finally, the chosen one has to go through the ultimate, somewhat nightmarish initiation rite: sit in a dark room full of 108 slaughtered buffaloes and goats, the floor shining with blood, each head illuminated by a lamp. The test of a true Kumari: she doesn't run. Even if later, some wish they should have.

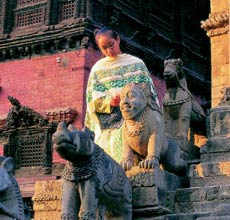

Attire

She is dressed in brilliant red cloth bordered with gold brocade, hair pulled back tight, forehead painted in emphatic black and white, bright vermilion around a third eye in the centre, and a crown of jewels on the head. Surrounded by burning bowls of camphor and devotees seeking her blessings, she sits calmly - immaculate, unperturbed and imposing. A goddess.

Formal schooling

In Nanimayya’s time, Kumaris weren't educated. The reasoning was damning: how can you teach a goddess anything that she already doesn't know.

By the 1990s Kumaris were given rudimentary schooling, though sadly there is a belief that teaching a goddess can lead to blindness. All that she earns as offerings during her reign go to the Kumari Ghar, the temple-cum-palace trust. It was the same even in the 1990s, though by then the government started giving a monthly sum of NR 1,000, (Indian Rs.640 at the 1997 rate), to unmarried Kumaris.

After the reign, the pain begins

"Being Kumari isn't bad, but back in the real world time has left you by."

"Sometimes I Wonder If Being A Kumari Was Lucky"

With the first menstruation, the spirit of Taleju starts leaving the body. And the troubles begin. The way is then "littered with thorns," Nanimayya would say. And all the demons of the mind gang up against you. She said that former unmarried Kumaris were far better off than she.

The plight of cast-off deities is a recurring theme with families of former Kumaris.

Former Kumaris are acutely conscious of how tough life gets once you aren't a goddess. They talk about the need to forge ahead, to accept reality in a place where the shadows of the past don't hover, memories don't haunt and they can again discover a sense of life.

Once cocooned and cosseted in the palace, later they are suddenly forced to find their way in a society that changes almost overnight from grandly medieval to starkly 21st century. They are left between two worlds, growing up extremely withdrawn, their former fame setting them apart, their present trauma making them lonelier still.

Marriage becomes elusive

One of the more suffocating aspects of the Kumari cult is the myth about marriage. When Anita today was a pretty young 22-year-old, her parents needed to look hard for a suitor.

An incarnation of Taleju, even a former one, for most, is difficult to take on as a life partner. Ask Nepalis where former Kumaris end up and many will tell you: as prostitutes or withered spinsters. "Marry one and you'll die," says one, half-mockingly. Myths are difficult to counter.

One former Kumari, Sunina Sakya, got married in the 1990s, concealing the fact that she had been a goddess. No longer a secret, there was marital tension and she refused to speak about her Kumari days.

Hearing all this, Anita - characteristically shy – would say that she did not want to get married. She was a misfit - no friends, did not go out, could not keep up with studies, and had failed her Class X examinations thrice. "Sometimes," she sighed, "I wonder if being a Kumari was lucky..."

"At my age I recall the happier times as a Kumari. It was like being a Goddess."

Fond memories, too

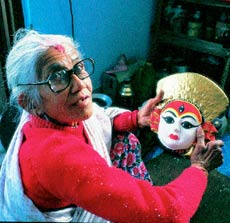

All former Kumaris, though, do retain some fond memories of their time as Kumaris. And with the passage of time, some of the pain dims and confusion turns to clarity. Hiramayya Sakya even forgot the more difficult parts of her life. She would recall the more happier times of playing with the pigeons, bright wings of light, spicy food or light-hearted banter in the Kumari Ghar.

The tough times - marrying late and after much difficulty, not being educated, starting out poor - have been reasoned away as lessons of life. Now, looking after her ailing husband, her grandchildren around her, she is at peace with her tryst with divinity. Though even after seven decades, some memories still shine brightly. "It was," she says simply, "like being a goddess".

‘Cast-off [former] deities’

Hiramayya

Born 1920

She succeeded in preserving only the happier memories of her few months as Kumari - a bad case of acne was a sign that Taleju had abandoned her. Hiramayya would tell her granchildren stories of the days she was a goddess. In her seventies there was a serenity and acceptance that comes with age, the inevitabilty of fate: "The gods willed it (her being a Kumari). It was a chance of being one with Him."

Nanimayya Sakya

Born in 1954

By the time she was in her 40s, Nanimayya Sakya struggled hard to make both ends meet as a pharmacy shop owner.

"We are suddenly left with nothing," she would say.

In a torn folder, in an old file box, Nanimayya kept some of the mementos of her Kumari days. A yellowed photograph, an old newspaper article, some gold brocade - all kept away from her husband who hated being reminded of that phase in her life. So did she, bitter for decades after ceasing tobe a Kumari. "While as Kumari everything was wonderful, later things became so tough, so difficult to overcome."

She married a man who did not like her talking about her Kumari days. She ran a small chemist shop, filling out prescriptions, or just doing the usual household chores. She craved the ordinary. She had two daughters. When they were small, the priests came asking for Kumari candidates - she shooed them away. "All the problems came back to me...I decided it wasn't worth it for my daughters."

Sunina Sakya

She did not like talking about her Kumari reign. Some details about her are given in this article.

Anita Sakya

Born in 1975

For Anita Sakya the early years of her life seem "wasted" as she, in her 20s, struggled to get into university. Nobody has given much thought about what would happen to them once the goddess returns to ground.

Anita was pretty. In her early 20s she liked make-up. It was like a hangover from her Kumari days: she loved to line her eyes with kohl. At home Anita was still treated like a goddess, often not allowed to sit on the floor. She became moody, withdrawn and going outside meant the rooftop. She did not like to go out. People recognise her. A reminder of the past. She did not like that

Rasmila Sakya

Born c.1981

She was a living goddess from 1984-92.

From age three, for eight long years, she was worshipped as the Royal Kumari of Nepal. Always on display, she lived inside the red-brick palace with intricate wood carvings of almost every god in the Hindu pantheon. But she was the one pampered and feared the most.

An angry squeal would convince startled devotees that she was predicting imminent doom, a good-natured laugh, peace and prosperity. Every natural calamity would be attributed to her wrath and a bout of illness would foretell more.

And, once a year, the king of Nepal would bow down to the fidgeting girl-goddess - as he still does - to seek permission for another year of reign. For most Nepalis, this tradition, an amalgamation of myth and reality, remains a living and intrinsic part of their culture.

Then somebody else became a Kumari. After the end of her reign, the free fall from goddess to ordinariness was devastating. Years of being ogled at resulted in her being bitterly shy and, often, depression - pining, brooding over the past - left her wandering from room to room in her family's small house, buried in the labrynthine alleys of old Kathmandu.

As a Kumari she had no family, ate when she wanted to (who can deny a goddess?) and was carried everywhere. Back home, she had to grapple with reality. "She didn't even understand who we were and how to address us," said Pragyadevi, her mother. Rasmila made an effort to make friends, pick up the strands of her life and get good grades at school - but the past was never too far away.

Rasmila became an absolute antithesis of Taleju, the fierce demonslaying goddess of whom she was once a living incarnation.

Among her chattering happy family, Rasmila was particularly distant, lonesome. Often, she asked her mother in anguish why she ever became a Kumari. In an ironic twist of fate, she was chosen over her younger sister. At the age of 16 she was only in class eight. Children at school made fun of her, but the flip side was that the principal bowed to her.

Unscathed by the April 2015 earthquake

Keshav Pradhan, The Times of India, May 03 2015

April 2015’s earthquake could not change the daily worship of Kumari, Nepal's living virgin goddess, though her temple was located in the otherwise devastated Basantpur Durbar Square.

Kumari Ghar, a three-storey architectural marvel, stood unharmed in the midst of the rubble of temples and palaces.

Most temples that towered over Kumari Ghar -Kasthamandap which gave Kathmandu its name, Dusavatar, Maanju Deval (Shiva), Narayan, and Krishna temples - disappeared. The Swet Bhairav idol collapsed.

However, in Kumari Ghar no one was hurt

“Kumari Ghar withstood the earthquake because of Kumari's powers,“ said 48year-old Gautam Shakya, an 11th-generation caretaker of Kumari. At the time of the quake, Kumari was blessing devotees on the first floor of the wood-and-brick house. Tourists, mostly Chinese, were on the ground floor. “Kumari Ghar started swaying. After the tremors, the temples and palaces all around were in ruins, 88 people lay dead outside. Nothing happened to Kumari Ghar or the devotees and tourists inside.“

A guide asked the tourists to think of Kumari and hold on to the wooden pillars tight, recalled Gautam Shakya.. After the visitors left, Kumari, a sevenyear-old girl, was brought to the ground floor. Her darshan [beholding her in person] was stopped for some time.

However, every morning, karmacharyas (Newar priests) from Taleju Temple continued to arrive with offerings of flowers, akshata, dhup and samaya baji (typical Newari prasad).

Two lion statues guarding the entrance continued to stand as before. Outside Kumari Ghar, wooden beams and planks used for making Kumari's rath during Indrajatra, a festival that precedes Dussehra by a month, remained intact.

Barring the chipping of some slabs at its base, Taleju Temple was not damaged.

See also

Kathmandu: What the 2015 earthquake destroyed

Kumari/ Taleju (living goddess): Nepal