Parsi community: India

(→B) |

(→Parsis of Delhi) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

=Parsis of Delhi= | =Parsis of Delhi= | ||

| − | |||

[http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Film-screening-unites-Delhis-Parsis-05092015005013 ''The Times of India''], Sep 05 2015 | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Film-screening-unites-Delhis-Parsis-05092015005013 ''The Times of India''], Sep 05 2015 | ||

| Line 36: | Line 35: | ||

Novy Kapadia, a sports journalist and a Delhi University teacher, has seen the drop in numbers over time. “In the 1960s when I was in school, there were around 1,500 Parsis. The Zoroastrian community in Delhi has been very progressive and continues to be so. The massive decline in numbers is also because a lot of the younger generation has migrated to Canada, Australia and the US in search for better opportunities.“ he says. | Novy Kapadia, a sports journalist and a Delhi University teacher, has seen the drop in numbers over time. “In the 1960s when I was in school, there were around 1,500 Parsis. The Zoroastrian community in Delhi has been very progressive and continues to be so. The massive decline in numbers is also because a lot of the younger generation has migrated to Canada, Australia and the US in search for better opportunities.“ he says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =Parsis of Kolkata= | ||

| + | [https://indianexpress.com/article/research/the-story-of-calcuttas-parsi-community-once-thriving-now-dwindling-9853632/ Nikita Mohta, Feb 25, 2025: ''The Indian Express''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Seated gracefully on her couch in her South Kolkata residence, author Prochy N Mehta holds two of her most cherished publications on the history of the Parsi community. As she flips through the pages of one, memories of her father’s journey unfold. “My father, Rusi B Gimi, came to Calcutta from Bharuch in Gujarat in the 1940s,” she recalls. “Like many other Parsis from small towns and villages, he arrived in the city with ambition and hope.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gimi’s first home was the Parsee Dharamshala (guesthouse) in Bowbazar, a bustling neighborhood in North Calcutta, where newly arrived Parsis often sought refuge. Mehta shares that Gimi initially started a bucket factory. Later, he married the daughter of the gentleman who ran the dharamshala and eventually transitioned into advertising. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “My maternal grandfather wasn’t too pleased with this,” she chuckles. “He would chide my mother, saying, ‘You’re marrying a hoarding painter!’” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The history of the Parsis in India is both fascinating and enigmatic. Kisseh-e-Sanjan, an epic poem composed by Parsi priest Baman Kaikobad in AD 1600, remains the only known account of their migration to India in 636 CE to escape Arab persecution. It details their arrival in Sanjan, Gujarat. However, as Mehta notes, much of this narrative is steeped in historical fiction. Historians remain uncertain about the precise date, location, and number of Parsis who first arrived. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In her recent book, Who is a Parsi?, Mehta argues that Parsi migration was predominantly male-driven, with settlers intermarrying with Indian women. Over time, the community expanded across Gujarat, integrating into local economies and establishing trade networks. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the key trading hubs for the Parsis was Surat, where they engaged in commerce alongside Armenian brokers. When these brokers moved to Murshidabad, a prominent trading center in Bengal, it is likely that Parsi traders followed suit, eventually bringing them to Calcutta. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Pioneering Parsis of Calcutta, Mehta writes, “Till the early 1700s, when the British came to India, the Parsis existed as a tribe amongst the Hindus, many following Hindu customs and procedures.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The British presence, coupled with the Parsis’ growing involvement in trade with China, brought newfound affluence. They were appointed as middlemen for European merchants in trading and banking operations. Academic Dalia Ray, in The Parsees of Calcutta, notes that Parsis “served the Company as interpreters, contractors, and brokers.” This economic prosperity fostered a stronger sense of religious identity, leading to the establishment of Parsi places of worship and distinct funeral practices. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first documented Parsi in Calcutta, Dadabhai Behramji Banaji, arrived in 1765, the same year the Battle of Buxar ended with the Treaty of Allahabad, solidifying British rule in eastern India. A successful trader from Surat, ‘Banaji Seth’ was patronised by John Cartier, then-Governor of Bengal, and became the patriarch of the influential Banaji family, shaping Bengal’s commercial and industrial landscape. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As Calcutta prospered, more Parsis from Bombay and Gujarat followed. By 1797, as historian Dinyar Patel notes in The Banaji and Mehta Families: Forging the Parsi Community in Calcutta, a small group of Parsi traders controlled 11.2 percent of Calcutta’s non-European export trade with London, nearly matching the 11.4 percent held by local Hindu Bengali firms. This influence is particularly striking considering that the city’s Parsi population grew from just 141 in 1881 to 274 by 1901. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “My father was the first to put up a hoarding in India!” Mehta exclaims. However, when he began his journey, he was denied entry to Advertising Club meetings simply because he wasn’t English or part of the elite. Mehta says that class has always been a deep divide in society, highlighting the sharp contrast between the affluent Parsi Sethias (the upper class) and families like hers, who came from more modest backgrounds. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “That said, most Parsis in Calcutta were affluent, having come to the city in pursuit of wealth.” Shipping, Mehta recollects, was one of the key industries in which they thrived. Her father’s business, too, flourished over time, but his contributions extended beyond commerce. Deeply committed to social service, Gimi founded a school for children with hearing impairment. Fire temples also played a role in charity, funding medical treatments and children’s education. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A key part of community life was the Parsi Club on Maidan — a lush green expanse in the heart of the city. Established as a cricket club in 1908, “it soon became a vibrant hub for Calcutta’s Parsis, reflecting their deep engagement with sports,” says Mehta. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “It was an affable community — both economically prosperous and socially engaged.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | After Dadabhai Banaji’s arrival in 1765, other prominent Parsis followed, including Rustomji Cowasji Banaji in 1812. Rustomji built a thriving business in shipbuilding and the lucrative China trade, which was heavily tied to opium smuggling. His fortunes soared during the First Opium War (1839-1842). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Ray explains that as the capital of British India, Calcutta served as a key transit point between China and Bombay for the opium trade. While Indian opium and raw cotton were central to British commerce, private traders had monopolised opium marketing in China since 1786. By 1809, Parsi merchants had overtaken the Armenians, who had led the opium trade until. Shipping primarily in their own vessels, the Parsis controlled the trade in partnership with English private firms like Beale & Magniac and Jardine Matheson & Co from 1810 to 1842. “Thus, trade in opium and raw cotton became the mainstay of the Parsee Seths in Calcutta,” says Ray. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In June 1828, Rustomji founded the Sun Insurance Company and carried on a very extensive business. He, along with Dwarkanath Tagore, were the only Indian members selected in the executive committee of the Bengal Chamber of Commerce established in 1834. In July the same year, he was elected Director of the Union Bank. “The British also honoured him by appointing him among the twelve Justices of the Peace created in 1835,” notes Cyrus J Madan in his short essay The Parsis of Calcutta. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By 1837, not only did Rustomji own a fleet of 27 ships but also bought the Calcutta Docking Company, the Khidirpur Docks. Subsequently, Rustomji defied social norms by relocating his entire family from Bombay to Calcutta in 1838. “He also permitted the women of his family to relinquish the ‘purdah’ and mix freely with men,” adds Ray. He was known to generously contribute to famine funds, and was a member of the Committee for ‘the relief of the native poor’ established in 1833. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At the time, Calcutta had a notorious reputation for disease and filth. For the improvement of sanitation and water supply, Rustomji constructed a canal in the northern part of the city. To address the fire hazard, he excavated several tanks at his own expense. Among the hospitals founded with his donations include the first Fever Hospital, Native Hospital and Medical College Hospital. He died on April 16, 1852. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Seth Jamshedji Framji Madan was another notable Parsi. In 1885, at the age of 29, he established a wine and provisions business on Dharmatala Street (now Lenin Sarani). He later became a pioneering figure in India’s cinema industry. In honour of his contributions, the British government awarded him the OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) in 1918, followed by the CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) in 1923 — distinguished accolades within the British honorary system. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the Banajis, RD Mehta emerged as a figure of comparable stature. He carried forward their legacy through public office, philanthropy, and the opium trade. A member of the Asiatic Society, he also served as the vice president of the Indian Association — one of Calcutta’s leading political organisations — and as the municipal chairman of Maniktala in north Calcutta. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Both the Banajis and the Mehtas translated their commercial success into political and social capital… forging friendships with the city’s Bengali and British elite, and earning honours and appointments from the government,” writes Patel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fire temples were central to Calcutta’s Parsi community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The first, established by the Banaji family on September 16, 1839, operated at 26 Ezra Street until the 1970s, when street hawkers took over the site. The second, inaugurated at the Mehta family’s Atash Adaran on October 28, 1912, was later entrusted to Calcutta’s Zoroastrian Anjuman, transforming it from a private shrine into a community institution. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A report, cited by Mehta, from the centenary celebrations of the Seth Rustomji Cowasji Banaji Atash Adaran, held on August 26, 1939, stated: “A well-organised community dinner followed… About a thousand Parsis participated in it, marking the first time in the history of the Parsis of Calcutta that such a large number sat down to dinner together.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | “I was born a few years after India’s independence, a period that would alter the fate of the Calcutta Parsis,” Prochy Mehta says with a grim expression. In newly independent India, the struggles of the past were still fresh in people’s minds. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Prochy Mehta grew up hearing stories about Pherozeshah Mehta, a prominent Parsi leader from Bombay who played a key role in India’s fight against British rule. “My father would tell us, only occasionally,” she laughs, recalling a rare admission, “that he too went to jail for a year while in college in Poona (now Pune) for his role in anti-British agitations.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The role of Calcutta’s Parsis in India’s freedom struggle is often overlooked, though it was undeniably significant. “However, with the British departure, the Parsis began to lose the influence and prosperity they had once enjoyed,” she says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While Calcutta’s Parsis thrived in the 19th century, they were also deeply engaged in the political currents of the 20th century. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the mid-1880s, as the Indian National Congress was taking shape, RD Mehta maintained regular contact with Dadabhai Naoroji, the prominent nationalist leader who co-founded the Congress in 1885. He played a crucial role as a bridge between Naoroji and the Bengali intelligentsia, exemplifying how Parsi nationalists leveraged community ties for broader political engagement. “During the 1880s and 1890s, Mehta, it appears, was one of the most important points of contact in Calcutta for Naoroji,” observes Patel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Their correspondence sheds light on Mehta’s political stance — he was a typical early Congress moderate, advocating for political reform without demanding self-rule. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By 1906, as Naoroji was elected Congress president to mediate between moderates and radicals, Mehta remained supportive. Patel’s study of their letters, preserved in the National Library archives in New Delhi, highlights this connection. In one letter, Mehta wrote: “I am sure your [Naoroji] presence would tend to settle the matter down smoothly.” That same year, Naoroji stayed with the Mehtas during his visit to Calcutta for the Congress session. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Things changed drastically for Calcutta’s Parsi community with the emergence of the new nation. The opening of the Suez Canal shifted trade in favour of Bombay, diminishing Calcutta’s economic significance. “By the 1960s, Parsis began leaving the city, and the exodus worsened in the 1970s,” Prochy Mehta recounts. “They moved to Bombay and across the globe: Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada…” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite this mass migration, her family remained. “My father enjoyed remarkable social and economic leverage in the city, so we stayed. But that wasn’t true for all Parsis.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Prochy Mehta fondly reminisces about the community’s close-knit nature in the past. “The good old days,” she sighs. “We had unique ways of staying connected. One was a donated bus that shuttled elderly Parsis to the Parsi Club for tea and snacks.” She also recalls biannual trips to Globe Cinema near New Market for a free movie. “A Parsi owned the hall, and during the interval, we feasted on sweets and snacks!” she laughed before adding, “Such days are long gone.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Today, Calcutta’s Parsi population has dwindled to around 350, with only 30 children under the age of 20 and nearly 80 people over the age of 80. “We are now a shrinking and aging community.” Efforts to revive the community, such as campaigns urging Parsis to have more children, have failed. Both Mehta and Patel point out that many young Parsis today choose not to marry or have children, and interfaith marriages have further contributed to the decline. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Minorities Commission of India recognises Parsis as a minority group alongside Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists, and Jains. “More than a community, Parsis today are holding onto their wealth,” Mehta concludes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Communities|P PARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIA | ||

| + | PARSI COMMUNITY: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|P PARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIA | ||

| + | PARSI COMMUNITY: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|PARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIA | ||

| + | PARSI COMMUNITY: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|D PARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIAPARSI COMMUNITY: INDIA | ||

| + | PARSI COMMUNITY: INDIA]] | ||

=Parsis of Mumbai= | =Parsis of Mumbai= | ||

Revision as of 12:15, 13 April 2025

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Parsi Sects

(From People of India/ National Series Volume VIII. Readers who wish to share additional information/ photographs may please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.)

Synonyms: Zoroastrian [West Bengal]

Groups/subgroups: Behdin, Fassalis, Kadmi, Shahenshai [West Bengal]

- Sects (sections): Gujarat, Kadmi, Shahanshahi in Bombay, Thana and Poona [R.E. Enthoven]

Surnames: Badivala, Dastur, Guzdar, Parakh, Sethna [West Bengal]

Parsis of Delhi

The Times of India, Sep 05 2015

Dharvi Vaid

Film screening unites Delhi's Parsis

The story of the community in Delhi has been somewhat different. Its Parsi community is small -it has only around 700 members. But it took steps nearly 45 years ago to arrest the drastic slide in its numbers. Its city association, the Delhi Parsi Anjuman, allowed inter-community marriages way back in the 1970s. It was probably the first anjuman to do so. “We allowed non-Parsi spouses to be members of the anjuman,“ says Adil Nargolwala, honorary secretary of the anjuman who is married to a non-Parsi.

Today , around 40% of Delhi's Parsis marry outside their community . Children from all such marriages are allowed into the Zoroastrian faith, of fered scholarships and other benefits and are free to participate in the community's cultural activities. Other anjumans only allow this if the father is a Parsi. “The most important thing today is for communities to live together in peace,“ says Dadi E Mistry , patron at the city anjuman.

Nargolwala points out that in cities like Mumbai, Pune and parts of Gujarat, the rules governing marriage and rituals are far more stringently applied. But Delhi has fewer Parsis and they are scattered around the city . This makes it possible to be more liberal with rules governing family life. “It is hard to find a Parsi spouse in Delhi today . Our social circles include people from all communities. You are quite likely to marry a non-Parsi in this situation,“ says Nargolwala.

The anjuman is also making an effort to sensitize younger Parsis to their religion and culture. There are occasional classes on Zoroastrian history and camps for children. “In our time our grandmothers used to teach us about our history and culture.Now we host groups of younger Parsis once every six weeks,“ says Mistry .

Novy Kapadia, a sports journalist and a Delhi University teacher, has seen the drop in numbers over time. “In the 1960s when I was in school, there were around 1,500 Parsis. The Zoroastrian community in Delhi has been very progressive and continues to be so. The massive decline in numbers is also because a lot of the younger generation has migrated to Canada, Australia and the US in search for better opportunities.“ he says.

Parsis of Kolkata

Nikita Mohta, Feb 25, 2025: The Indian Express

Seated gracefully on her couch in her South Kolkata residence, author Prochy N Mehta holds two of her most cherished publications on the history of the Parsi community. As she flips through the pages of one, memories of her father’s journey unfold. “My father, Rusi B Gimi, came to Calcutta from Bharuch in Gujarat in the 1940s,” she recalls. “Like many other Parsis from small towns and villages, he arrived in the city with ambition and hope.”

Gimi’s first home was the Parsee Dharamshala (guesthouse) in Bowbazar, a bustling neighborhood in North Calcutta, where newly arrived Parsis often sought refuge. Mehta shares that Gimi initially started a bucket factory. Later, he married the daughter of the gentleman who ran the dharamshala and eventually transitioned into advertising.

“My maternal grandfather wasn’t too pleased with this,” she chuckles. “He would chide my mother, saying, ‘You’re marrying a hoarding painter!’”

The history of the Parsis in India is both fascinating and enigmatic. Kisseh-e-Sanjan, an epic poem composed by Parsi priest Baman Kaikobad in AD 1600, remains the only known account of their migration to India in 636 CE to escape Arab persecution. It details their arrival in Sanjan, Gujarat. However, as Mehta notes, much of this narrative is steeped in historical fiction. Historians remain uncertain about the precise date, location, and number of Parsis who first arrived.

In her recent book, Who is a Parsi?, Mehta argues that Parsi migration was predominantly male-driven, with settlers intermarrying with Indian women. Over time, the community expanded across Gujarat, integrating into local economies and establishing trade networks.

One of the key trading hubs for the Parsis was Surat, where they engaged in commerce alongside Armenian brokers. When these brokers moved to Murshidabad, a prominent trading center in Bengal, it is likely that Parsi traders followed suit, eventually bringing them to Calcutta.

In Pioneering Parsis of Calcutta, Mehta writes, “Till the early 1700s, when the British came to India, the Parsis existed as a tribe amongst the Hindus, many following Hindu customs and procedures.”

The British presence, coupled with the Parsis’ growing involvement in trade with China, brought newfound affluence. They were appointed as middlemen for European merchants in trading and banking operations. Academic Dalia Ray, in The Parsees of Calcutta, notes that Parsis “served the Company as interpreters, contractors, and brokers.” This economic prosperity fostered a stronger sense of religious identity, leading to the establishment of Parsi places of worship and distinct funeral practices.

The first documented Parsi in Calcutta, Dadabhai Behramji Banaji, arrived in 1765, the same year the Battle of Buxar ended with the Treaty of Allahabad, solidifying British rule in eastern India. A successful trader from Surat, ‘Banaji Seth’ was patronised by John Cartier, then-Governor of Bengal, and became the patriarch of the influential Banaji family, shaping Bengal’s commercial and industrial landscape.

As Calcutta prospered, more Parsis from Bombay and Gujarat followed. By 1797, as historian Dinyar Patel notes in The Banaji and Mehta Families: Forging the Parsi Community in Calcutta, a small group of Parsi traders controlled 11.2 percent of Calcutta’s non-European export trade with London, nearly matching the 11.4 percent held by local Hindu Bengali firms. This influence is particularly striking considering that the city’s Parsi population grew from just 141 in 1881 to 274 by 1901.

“My father was the first to put up a hoarding in India!” Mehta exclaims. However, when he began his journey, he was denied entry to Advertising Club meetings simply because he wasn’t English or part of the elite. Mehta says that class has always been a deep divide in society, highlighting the sharp contrast between the affluent Parsi Sethias (the upper class) and families like hers, who came from more modest backgrounds.

“That said, most Parsis in Calcutta were affluent, having come to the city in pursuit of wealth.” Shipping, Mehta recollects, was one of the key industries in which they thrived. Her father’s business, too, flourished over time, but his contributions extended beyond commerce. Deeply committed to social service, Gimi founded a school for children with hearing impairment. Fire temples also played a role in charity, funding medical treatments and children’s education.

A key part of community life was the Parsi Club on Maidan — a lush green expanse in the heart of the city. Established as a cricket club in 1908, “it soon became a vibrant hub for Calcutta’s Parsis, reflecting their deep engagement with sports,” says Mehta.

“It was an affable community — both economically prosperous and socially engaged.”

After Dadabhai Banaji’s arrival in 1765, other prominent Parsis followed, including Rustomji Cowasji Banaji in 1812. Rustomji built a thriving business in shipbuilding and the lucrative China trade, which was heavily tied to opium smuggling. His fortunes soared during the First Opium War (1839-1842).

Ray explains that as the capital of British India, Calcutta served as a key transit point between China and Bombay for the opium trade. While Indian opium and raw cotton were central to British commerce, private traders had monopolised opium marketing in China since 1786. By 1809, Parsi merchants had overtaken the Armenians, who had led the opium trade until. Shipping primarily in their own vessels, the Parsis controlled the trade in partnership with English private firms like Beale & Magniac and Jardine Matheson & Co from 1810 to 1842. “Thus, trade in opium and raw cotton became the mainstay of the Parsee Seths in Calcutta,” says Ray.

In June 1828, Rustomji founded the Sun Insurance Company and carried on a very extensive business. He, along with Dwarkanath Tagore, were the only Indian members selected in the executive committee of the Bengal Chamber of Commerce established in 1834. In July the same year, he was elected Director of the Union Bank. “The British also honoured him by appointing him among the twelve Justices of the Peace created in 1835,” notes Cyrus J Madan in his short essay The Parsis of Calcutta.

By 1837, not only did Rustomji own a fleet of 27 ships but also bought the Calcutta Docking Company, the Khidirpur Docks. Subsequently, Rustomji defied social norms by relocating his entire family from Bombay to Calcutta in 1838. “He also permitted the women of his family to relinquish the ‘purdah’ and mix freely with men,” adds Ray. He was known to generously contribute to famine funds, and was a member of the Committee for ‘the relief of the native poor’ established in 1833.

At the time, Calcutta had a notorious reputation for disease and filth. For the improvement of sanitation and water supply, Rustomji constructed a canal in the northern part of the city. To address the fire hazard, he excavated several tanks at his own expense. Among the hospitals founded with his donations include the first Fever Hospital, Native Hospital and Medical College Hospital. He died on April 16, 1852.

Seth Jamshedji Framji Madan was another notable Parsi. In 1885, at the age of 29, he established a wine and provisions business on Dharmatala Street (now Lenin Sarani). He later became a pioneering figure in India’s cinema industry. In honour of his contributions, the British government awarded him the OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) in 1918, followed by the CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) in 1923 — distinguished accolades within the British honorary system.

After the Banajis, RD Mehta emerged as a figure of comparable stature. He carried forward their legacy through public office, philanthropy, and the opium trade. A member of the Asiatic Society, he also served as the vice president of the Indian Association — one of Calcutta’s leading political organisations — and as the municipal chairman of Maniktala in north Calcutta.

“Both the Banajis and the Mehtas translated their commercial success into political and social capital… forging friendships with the city’s Bengali and British elite, and earning honours and appointments from the government,” writes Patel.

Fire temples were central to Calcutta’s Parsi community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The first, established by the Banaji family on September 16, 1839, operated at 26 Ezra Street until the 1970s, when street hawkers took over the site. The second, inaugurated at the Mehta family’s Atash Adaran on October 28, 1912, was later entrusted to Calcutta’s Zoroastrian Anjuman, transforming it from a private shrine into a community institution.

A report, cited by Mehta, from the centenary celebrations of the Seth Rustomji Cowasji Banaji Atash Adaran, held on August 26, 1939, stated: “A well-organised community dinner followed… About a thousand Parsis participated in it, marking the first time in the history of the Parsis of Calcutta that such a large number sat down to dinner together.”

“I was born a few years after India’s independence, a period that would alter the fate of the Calcutta Parsis,” Prochy Mehta says with a grim expression. In newly independent India, the struggles of the past were still fresh in people’s minds.

Prochy Mehta grew up hearing stories about Pherozeshah Mehta, a prominent Parsi leader from Bombay who played a key role in India’s fight against British rule. “My father would tell us, only occasionally,” she laughs, recalling a rare admission, “that he too went to jail for a year while in college in Poona (now Pune) for his role in anti-British agitations.”

The role of Calcutta’s Parsis in India’s freedom struggle is often overlooked, though it was undeniably significant. “However, with the British departure, the Parsis began to lose the influence and prosperity they had once enjoyed,” she says.

While Calcutta’s Parsis thrived in the 19th century, they were also deeply engaged in the political currents of the 20th century.

In the mid-1880s, as the Indian National Congress was taking shape, RD Mehta maintained regular contact with Dadabhai Naoroji, the prominent nationalist leader who co-founded the Congress in 1885. He played a crucial role as a bridge between Naoroji and the Bengali intelligentsia, exemplifying how Parsi nationalists leveraged community ties for broader political engagement. “During the 1880s and 1890s, Mehta, it appears, was one of the most important points of contact in Calcutta for Naoroji,” observes Patel.

Their correspondence sheds light on Mehta’s political stance — he was a typical early Congress moderate, advocating for political reform without demanding self-rule.

By 1906, as Naoroji was elected Congress president to mediate between moderates and radicals, Mehta remained supportive. Patel’s study of their letters, preserved in the National Library archives in New Delhi, highlights this connection. In one letter, Mehta wrote: “I am sure your [Naoroji] presence would tend to settle the matter down smoothly.” That same year, Naoroji stayed with the Mehtas during his visit to Calcutta for the Congress session.

Things changed drastically for Calcutta’s Parsi community with the emergence of the new nation. The opening of the Suez Canal shifted trade in favour of Bombay, diminishing Calcutta’s economic significance. “By the 1960s, Parsis began leaving the city, and the exodus worsened in the 1970s,” Prochy Mehta recounts. “They moved to Bombay and across the globe: Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada…”

Despite this mass migration, her family remained. “My father enjoyed remarkable social and economic leverage in the city, so we stayed. But that wasn’t true for all Parsis.”

Prochy Mehta fondly reminisces about the community’s close-knit nature in the past. “The good old days,” she sighs. “We had unique ways of staying connected. One was a donated bus that shuttled elderly Parsis to the Parsi Club for tea and snacks.” She also recalls biannual trips to Globe Cinema near New Market for a free movie. “A Parsi owned the hall, and during the interval, we feasted on sweets and snacks!” she laughed before adding, “Such days are long gone.”

Today, Calcutta’s Parsi population has dwindled to around 350, with only 30 children under the age of 20 and nearly 80 people over the age of 80. “We are now a shrinking and aging community.” Efforts to revive the community, such as campaigns urging Parsis to have more children, have failed. Both Mehta and Patel point out that many young Parsis today choose not to marry or have children, and interfaith marriages have further contributed to the decline.

The Minorities Commission of India recognises Parsis as a minority group alongside Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists, and Jains. “More than a community, Parsis today are holding onto their wealth,” Mehta concludes.

Parsis of Mumbai

Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) elections, 2015

The Times of India, Oct 11 2015

Nergish Sunavala

Punchayet 2nd largest land owner in Mumbai

EVMs, 500 officers for big, fat Parsi elections

With less than a week to go for the Bombay Parsi Pun chayet (BPP) elections, aspiring trustees have been giving stump speeches at colonies across Mumbai.

Three can didates, canvassing together as “The Tremendous Three“ were speaking at Colaba's Cusrow Baug ¬ a citadel of lemon yellow buildings, green lawns and vintage Fiats. With over 5,000 apartments and many commercial establishments under its control, the BPP is the city's second-largest land owner after the Mumbai Port Trust and Cusrow Baug is by far its most lucrative property with flats selling from Rs 5 crore. Thus, it's no wonder that the poll is being taken very seriously by Mumbai's Parsi community , which numbers just 39,000. In the run-up to the October 18 polls, 500 election officers have been busy conducting mock drills, scouring the electoral rolls for duplications, arranging for ambulances at the five polling stations and pressing candidates to stick to a voluntary code of conduct, created for the first time in 100 years. Community papers and magazines ¬ one of which is owned by a candidate ¬ are rife with testimonials, voting FAQs and ads that can cost up to Rs 55,000.The expenditure cap has been limited to Rs 3 lakh. Aspirants are interrupting their chest-thumping rhetoric to give live demonstrations of the newly-introduced Electronic Voting Machines (EVM). At Cusrow Baug, one contender pulled out a dummy machine and began explaining the nitty-gritties of the process. “Each booth has two EVMs because a single machine has only 16 slots and there are 23 candidates,“ he told the hundred odd senior citizens, some of whom had expressed fears of “rigging“. “It's not a touch screen so `dabao' the button for the red light to come on,“ he added. Since five out of seven seats are up for grabs, voters can select up to five candidates. An exhaustive set of EVM FAQs, created by the BPP's election team, deals with every question imaginable from “Can I undo my selection?“ to “What if there is a power failure?“ to “Can I vote for the same candidate multiple times?“ Last year, India conducted the world's largest election when 81.4 crore people ¬ larger than the population of Europe ¬ cast their vote in 9.3 lakh polling stations fitted with 14 lakh EVMs. This election might be diminutive in comparison ¬ In the polls, a maximum of 15,000 Parsis are expected to cast their vote at five centres fitted with 100 EVMs ¬ but it's being arranged with the same earnestness. “At each centre, there will be an incharge polling officer and three to four assistant polling officers, “ he says.“There will be nearly 500 people, of which 230 will be polling agents from the candidates' side, and a hundred IT support staff for the EVM machines,“ he adds. One booth in each centre will be reserved for handicapped voters, and wheelchairs will be available too.

The entire process will cost the BPP Rs 25 lakh, says Dastoor. On election day , people will have to show their election cards and a government-sanctioned ID, their name will be ticked off an online electoral roll and their forefinger will be marked with indelible ink. A dry run of 150 voters has already been conducted in Khareghat Colony to evaluate how long each voter will take to complete the process and ensure that there are no hiccups. The results will be declared the same evening.One curious lacuna in this otherwise water-tight process is the identification of voters as Parsi. “Your passport, your Aadhar card, nothing mentions your religion,“ says Dastoor.

Population: dwindling, no, hurtling towards extinction

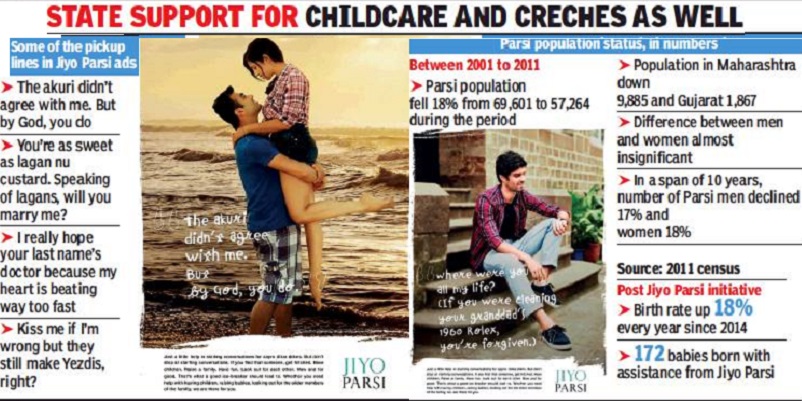

Jiyo Parsi: a Govt-Funded Initiative

Aimed at many other communities such an advertising campaign would have resulted in multi- crore rupee bounties for the heads of the copywriter and the models concerned (and, of course, bans).

Only a community whose poverty line equals the US middle-class life in PPP terms, a community in which almost everyone is a graduate, can get away with such a bright campaign.

These pickup lines aim to help young Parsis lift birth rates

After Govt-Funded Initiative, Births In Community Have Risen 18% Annually

Nergish.Sunavala@timesgroup.com

Mumbai:

From 2001 to 2011, the Parsi population fell from 69,601 to 57,264—an approximate 18% drop. There are eight deaths for every two births. According to various studies, the main culprits are low fertility caused by late or no marriages, single-child families, immigration, intermarriage, separation and divorce.

Thanks to the Jiyo Parsi initiative, which has received Rs 22 crore from the Indian government, there is now widespread awareness in the community about the dwindling population. The birth rate has increased 18% every year since 2014, resulting in 172 babies born with assistance from Jiyo Parsi.

Jiyo Parsi is a government-funded initiative to increase the community’s population through medical fertility assistance and advocacy.

While the campaign’s first phase focused on spreading awareness, the second highlighted the advantages of starting a family early. The initiative’s third phase focuses on the vital role senior citizens can play in supporting working parents.

With this in mind, Jiyo Parsi Care provides financial incentives to able senior citizens who take on the responsibility of looking after the community’s children. They will receive Rs 3,000 per child until the children are 10 years old.

Couples with a combined annual income of less than Rs 15 lakh will also be eligible for creche and childcare support, which is capped at Rs 4,000 per month per child until the child is eight years old. And if they have an elder relative staying with them to help with childcare, they will receive an additional Rs 4,000 per month per senior person. To be eligible for the latter scheme, though, the family’s incomes should be less than Rs 10 lakh per annum.

“Jiyo Parsi now offers a complete service for young people with counselling, advocacy, persuasion and financial help and support in both having a baby and looking after the baby and their family elders,” says Shernaz Cama, president of Parzor Foundation, which is implementing the scheme along with a number of community organizations and TISS.

Pickup lines

“Girl you’re so precious, you put the dhan into dhansak,” reads a newly released Jiyo Parsi advertisement, which is part of the campaign’s third phase, ‘Jiyo Parsi Care’. This pickup line was invented to help young Parsis who tend to get “tongue tied” when initiating a conversation around matrimony.

“We are providing icebreakers. If you don’t know what to say, use our lines and the other person will understand what you have in mind,” says Sam Balsara, chairman of Madison World, which conceptualised the campaign.

2014> 21: a success

Ambika Pandit, June 14, 2021: The Times of India

The work from home norm during Covid-hit 2020 delivered some good news for the Parsi community which saw a record 61 births, assisted through the Centre’s Jiyo Parsi scheme aimed at arresting a decline in the community’s numbers which added up to all of 57,000 in the 2011census.

Launched in 2013-14, the scheme, supported by the minority affairs ministry, has seen an additional 22 births this year with the total number of newborns now standing at 321 as of June. The gains seem small but are precious for the community that has contributed handsomely to Indian national life before and after independence.

A fast dwindling population count that stood at 1.14 lakh in 1941 prompted the Centre to launch the Jiyo Parsi scheme in 2013-14. A year-wise break-up shows that while in the first year, 16 babies were born, the number rose to 38 the next year, went down to 28 in 2016 and then rose to 58 in 2017. It dipped to 38 in 2018 but grew to 59 in 2019 and 61 in 2020.

The data regarding 321 children pertains largely to couples who benefited from medical reimbursements offered under Jiyo Parsi for medical interventions like fertility treatments, assisted reproductive technologies and counselling to seek medical help given the low birth rates in the community.

“Going by the data, 2020 saw a new high and this, in a way, can be attributed to many couples starting fertility treatment during the pandemic as work from home gave them flexibility in working hours and made visits to hospitals and clinics less stressful. One saw couples taking this opportunity — of the entire family being together at all times — as a good opportunity to decide to start a family,” said Shernaz Cama, director of Unesco Parzor and national director of Jiyo Parsi scheme.

She said the other reason for the increase in birth rates was due to changes in the Jiyo Parsi scheme in 2017. The HOC (health of the community) component took care of elderly dependants in a family and also brought in a child care scheme that helped couples with financial assistance. “In the medical category, we also included and ensured financial help would be extended for those who conceived through ART right up to delivery and discharge from hospital,” Cama added.

However, the pandemic brought its own share of challenges. For instance, Cama said, a woman who conceived through ART tested positive for Covid-19 during her sixth month of pregnancy and was hospitalised for a few weeks. After treatment, she has now delivered a healthy baby. Shahnaaz Dalal, 29, from Mumbai, spoke to TOI about her journey. She conceived in the middle of last year and was supported under the Jiyo Parsi scheme which helped her tide through the tough phase and give birth to a daughter in March.

'Poverty' line

2009-10: A poor Parsi: One who earns below 50,000/m

[ From the archives of the Times of India]

Rosy Sequeira TNN

The Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) told the Bombay high court that it considers a Parsi who earns less than Rs 50,000 a month to be “poor” and hence eligible for allotment of a flat at subsidized rent. A division bench of Justices P B Majmudar and Ramesh Dhanuka was hearing a petition filed by RohintonTaraporewala against BPP.

Taraporewala, who is in his 60s, lives in Tarapur. He has contended in his plea that he is “poor and eligible’’ for housing, but BPP has allotted flats at PanthakyBaug in Andheri to people who are “richer” than him. He also said that he and his wife are ailing and have to live in Mumbai to avail of medical treatment.

When the matter came up for hearing, Taraporewala’s lawyer was not present. BPP advocate Percy Gandhi said a copy of the petition had not been served to his client. “He is not poor and has moved court because he was not allotted a flat at PanthakyBaug. He is very rich and has acres of land. These flats are for the poor and needy,’’ said Gandhi.

To a query from the judges as to who is defined as poor by the BPP, Gandhi replied, “A person earning income below Rs 50,000 a month is regarded as poor.’’ Justice Majmudar remarked, “We have not come across any poor Parsi.”

On October 15, 2009, the high court allowed BPP to sell 108 flats at PanthakyBaug at rates approved by the Charity Commissioner to cross-subsidize housing for needy Parsis. Some 300 flats are to be constructed and given on a merit-rating scheme.

Gandhi submitted that the108 flats “are to be sold to poor Parsis’’ and as Taraporewala is “not poor”, he was not allotted a flat. The judges have adjourned the matter for two weeks.

The Bombay Parsi Punchayet told the Bombay HC that it considers a Parsi who earns less than Rs 50,000 a month to be “poor” and hence eligible for allotment of a flat at subsidized rent

2012:‘Poor Parsi is one who earns up to ₹90,000 a month’

Rosy Sequeira TNN

The Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) told the Bombay high court that it had revised the definition of a poor Parsi as one who earns up to Rs 90,000 a month, in order to be eligible for a subsidized community apartment. The BPP, which controls over 5,000 flats in the city, had earlier fixed this at under Rs 50,000 a month. There are an estimated 45,000 Parsis in Mumbai.

Incidentally, the Planning Commission had pegged the minimum sustenance level required for a poor person in an urban area at Rs 29 a day.

An affidavit was filed by BPP chairman Dinshaw Mehta in response to a petition by Dahanu resident RohintonTaraporewala, 65, challenging the non-allotment of a flat to him at PanthakiBaug, Andheri. Earlier, Taraporewala had submitted the names of those who were allotted flats despite earning above Rs 50,000 a month.

In his April 17, 2012 reply, Mehta refuted Taraporewala’s claim of being a “poor, needy and deserving Parsi”. He said after the HC, on October 15, 2009, allowed BPP to sell flats on ownership basis, the trustees adopted criteria for allotment. Preference was to be given to those who want to settle down after marriage. “All applicants with incomes exceeding Rs 90,000 per month or with assets of more than Rs 25 lakh were to be eliminated,” Mehta stated.

It was also decided to give low priority to applicants residing outside Mumbai. BPP invited applications for purchase of flats in buildings A and B at PanthakiBaug. Mehta claimed that Taraporewala’s application stated he owns 17 acres land in Vangaon, Dahanu, along with a farmhouse — a 2,000 sqft two-storeyed bungalow.

“On a conservative estimate, this would be valued at Rs 1.5 to Rs 3 crore,’’ he added. Further, as per his income-tax returns, Taraporewala had a monthly income exceeding Rs 90,000 a month.

His assets include his various immovable properties and fixed deposits amounting to over Rs 25 lakh. On the basis of his financial status he was not entitled to be allotted a flat at PanthakiBaug, Mehta added. Mehta said the reason Taraporewala gave for allotment was that there were few basic hospital facilities in the village. He suffers from high blood pressure, prostate problem, diabetes and heart problems while his wife suffers from depression and anxiety.

A ‘poverty- stricken’ Parsi earns like the US middle class

Indpaedia’s note:

In 2012, $1 (USD) was equal to ₹49.455 in nominal terms and ₹16.013 in terms of PPP (purchasing power parity).OECD data

Hence the Parsi poverty line of ₹90,000 a month was $1,820 per month in nominal (dollar) terms and a whopping US $5,621 in terms of PPP.

According to the USA’s HHS, the Poverty Guideline for the USA in 2012 was an income of $930 per month ($11,170 a year) for a household with 1 person in the family, and $1,260 per month ($15,130 a year) for a household with 2 persons in the family.

Few elderly Parsis have families bigger than that. (How every admirer of this great community wishes that they did!)

This means that every ‘poverty- stricken’ Parsi living alone is twice as rich as a poverty- stricken American, i.e. the Parsi earns twice as many US dollars. But considering that most things in India are much cheaper that in the USA, a ‘poverty- stricken’ Parsi living alone in India has a standard of living almost seven times higher than that of a poverty- stricken US citizen.

In 2012, Forbes reported, based on the findings of a then-recent poll by the Marist Institute for Public Opinion, that ‘The Salary That Will Make You Happy is Less Than $75,000’

A ‘poverty- stricken’ Parsi earned $67,589 in 2012, almost equal to what most Americans aspired for.

It also means that in nominal terms a ‘poverty- stricken’ Parsi earns as much as a lower-middle class American and in terms of PPP lives like middle-class Americans in highly respectable jobs do.

And compared to Indians?

In 2012, Major Generals in the Indian Army, Inspectors General of Police and IAS Joint Secretaries earned the same as those below the Parsi poverty line. So did the President of India and the Governors of Indian states. See (Salaries of legislators (PM, CMs, Ministers, MPs, MLAs...): India)

B

Genes

Parth Shastri | TNN, Oct 22, 2022: The Times of India

When the Parsis arrived on Gujarat’s shore around the 8th century CE and sought asylum, it is said the local king sent them a glass that was full of milk. The Parsi elders added sugar to the milk and returned it, to indicate they would blend with the local population.

Now a study of the Parsi population shows this tale of blending might well be true at the genetic level. Titled ‘Like Sugar in Milk: Reconstructing the genetic history of the Parsi population’, the study was published in the ‘Genome Biology’ journal of SpringerNature. Its authors, Gyaneshwar Chaubey, Qasim Ayub, Niraj Rai and Satya Prakash, among others, belong to research institutions in Estonia, India, the UK, Pakistan and New Zealand.

The scientists found the Parsi population has a mix of genetic markers from not only the Neolithic Zagros region of Iran (ancient Paras/Persia, hence the nameParsi) but also Gujarat in India and Sindh in Pakistan. This genetic mixing, however, took place a long time ago, as the later Parsis married strictly within the community. That’s why the Parsi population now provides‘homozygous’ results (having similar/ identical alleles or DNA sequences).

Rai, a senior scientist at Lucknow-based Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleosciences (BSIP), said the study is exhaustive as it takes intoconsideration about 40 generations over 1,160 years. “While it confirms the lore of Parsis’ arrival genetically, it also throws light on the community’s settling down in the region. The study indicates the earlier settlers might have been men who married in the local population. But it happened centuries ago, and we find the Gujarati and Sindhi traces only through mitochondrial lineages. ”

The paper suggests two possibilities for the SouthAsian genetic markers among the Parsis. “We observed 48% South-Asianspecific lineages (haplogroups M2, M3, M5, and R5) among the ancient Parsi samples… These haplogroups might have been carried by the migration of Zoroastrian refugees. Second, they might have resulted from the assimilation of local females during the initial settlement. The comparison of ancient and modern samples thus identifiedmaternal lineages that can be considered as founding. ”

It adds that the Y-chromosome (male) profiles of Indian and Pakistani Parsi populations show a higher frequency of Middle-Eastern-specific lineages than South Asian ones. Which suggests the male ancestors of the Parsis in both countries were predominantly from the Middle East. Hence, the study confirms that “the Parsis are genetically closer to Iranian and Caucasian populations than those in South Asia”. It also provides evidence of “female gene flow from South Asians to the Parsis”.

Rai said the study also throws light on the migration pattern of Parsis, their assimilation in the local milieu, and most importantly, it establishes India’s western coast, including Gujarat, as a cultural potpourri. “The region was welcoming to incoming groups, and over the centuries we saw an influx of various faiths without persecution, be it Jews or Parsis,” he said.

HISTORICAL VIGNETTES

"Super Six" cyclists, 1920s

Sharmila Ganesan Ram, June 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Sharmila Ganesan Ram, June 3, 2021: The Times of India

In the 1920s, long before the dawn of fake news, one Chinese man was told that Rabindranath Tagore had composed the Gujarati national anthem of the Parsi community that went: "We are old Zoroastrians". The culprit was Adi Hakim, one of the "Super Six" khaki-clad Parsi cyclists who had endured brass band music as they set off from Lamington Road's Gilder Tank ground on October 15, 1923 to fulfil a lofty dream: putting India on the global sports map by pedalling through the war-torn streets, snow-capped peaks, bone-melting deserts and dacoit-infested mountains across the world.

While three of these muscular Indian globetrotters from the Bombay Weightlifting Club – Keki Pochkhanawala, Nariman Kapadia and Gustad Hathiram – abandoned their saddles midway, the other three – Chira Bazaar's athletic Rustom Bhumgara, six-foot-tall foodie Jal Bapasola and Dadar Parsi Colony's gregarious Hakim – would return to Gilder Tank ground from their five-years-and-71000-km-long adventure, sunburnt and jubilant.

Here, hordes of motorists, cyclists and gaily-clad Parsi women in omnibuses would watch Bhumgara recall his time working as a waiter in America and chuckle as Hakim would remember a man in China who sang the Chinese national anthem and then insisted that Hakim reciprocate by singing "the national anthem of the Parsis". Under duress, Hakim had invoked a Gujarati hymn and, when asked who had composed it, uttered the name of the Bengali legend who wrote India's national anthem.

Only the well-to-do in Bombay could afford cycles in those fraught, pre-Independence decades between 1920 and 1942 when 12 Parsi cyclists from the city had set off on five separate journeys that made them the first Indian eyewitnesses to the ravages of war in Europe, a strife-torn East Asia and the Great Depression in America.

Of these cyclists – who pedalled alone and in groups across the deserts of Sahara, rainforests of Amazon and mountains of the Alps – eight were successful. Some had knelt before Pope Pius XI, some had rubbed shoulders with the likes of Benito Mussolini and Franklin Roosevelt. For lack of protective eyewear, one of these globe-trotters lost his sight and died a blind man. But the wealth of memories, photographs and meticulous notes they left behind are anthropological eye-openers if you ask Anoop Babani, a Goa-based cyclist who had tracked down the families of these early adventurers for photo exhibitions in 2019.

According to Babani, 30-year-old sports journalist Framroz J Davar's 1923 cycling expedition – pedalling 9000 kms alone from Bombay to Vienna and then covering 52 countries along with Austrian cyclist Gustav Sztavjanik over seven years – was the most perilous of the lot. While Davar, who started his journey three months after Super Six, had drawn inspiration from his fellow Parsi, Scout-uniform-clad predecessors, what had apparently imbued them with unprecedented daredevilry was a public lecture in the city by a foreigner who had been walking around the world.

Their audacious dream – sculpted in between bodybuilding sessions at Grant Road's Bombay Weightlifting Club – had to be protected from their families for fear of opposition. So with savings of Rs 2000 each, a few clothes, medicine boxes, cycle gear, a second hand compass and crude copies of the world map, the Super Six had left quietly atop sturdy British Royal Benson cycles fitted with Dunlop tyres. It seems Britain's Raleigh Cycle Company in Bombay had refused to sponsor cycles for their tour but when they rode into London, Raleigh was pleading with them to use their brand. Why the change of heart? "Frankly, we didn't believe you boys would make it," said officials at Raleigh. While the shy and imposing Bapasola served as the team's human GPS with his map-reading proficiency, the rugged, quick-witted auto mechanic Bhumgara, who repaired his mates' cycles through the expedition, drew easy attention from women abroad.

By the time Bhumgara's parents found out where their son was, the Super Six had drunk water from mud pools in Bikaner populated by half-submerged buffaloes, hauled their bikes up marauder-infested mountains of Baluchistan and reached Persia, the land of their ancestors. Here, the robust trio would earn princely sums by performing antics such as splintering a stone on their chest with big hammers and dragging a car full of passengers with a rope held between their teeth. In Tehran, they would even be offered military jobs by then War Minister and would-be Prime Minister Reza Shah Pahlavi.

Their wordless flirtation with veiled Persian beauties in Iran was followed by another silent transaction: in Baghdad, where they would bribe Bedouins with cigarettes hidden in their cycle grips. Later, after crossing the starvation-inducing Syrian-Mesopotamian desert, they found themselves being mistaken for German spies in a remote Italian village and spent a night in jail before being let off the next morning with apologies.

"Tumbled down homesteads, torn-up earth, heaps of empty shells, steel helmets, destroyed cannons and their carriages, deserted fields and solitary remains of some human skeletons half peering through its earthly covering..," they wrote about the remnants of war they saw in prostitution-ridden Europe.

Their happiest days and smoothest roads would arrive in England, from where they took a steamer to New York – a city that made Hathiram announce to the others that he didn't plan to return home. "Think that I drowned in the Atlantic, my friends, for the Gustad you knew is now no more," said the letter his mates found under the hotel door. Without Hathiram, Kapadia – who had returned home from Tehran "for personal reasons" – and Pochkhanawala – who reverted from London to look after his ailing father – the group was now half its size. And at many points, they were tempted to take a boat home.

If America's insulting immigration authorities repulsed them, so did the behaviour of French officials towards Indians in then Indo-China (present-day Vietnam) where the trio was put behind bars on charges of 'bringing into hatred and the contempt of (French) government of Indo-China.'

In politically volatile China, they encountered floods, heat waves, bandits and soldiers who pointed guns to their forehead. All these hardships were temporarily offset by Miss Peggy, a French blonde they met in Rangoon whose cheerful company they pined for on the journey back into an alien-seeming Bombay. The city had sprouted trains, motorised buses and rising waves of migrants who lived in rented accommodations. Merely days before the trio's rousing homecoming, in fact, a group of boarders had issued 'Hints to Bombay Boarding House Landladies', requesting some conveniences which included: "Any new dishes (food items) should first be tried on the dog. Boarders do not hold themselves responsible for the burial expenses of the dog.”