Awadhi, language

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> Additional information ma...") |

Latest revision as of 20:05, 17 April 2025

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

[edit] A backgrounder

[edit] As of 2025

Nikita Mohta, April 12, 2025: The Indian Express

From: Nikita Mohta, April 12, 2025: The Indian Express

From: Nikita Mohta, April 12, 2025: The Indian Express

Origins of Awadhi

Awadhi is widely spoken in Uttar Pradesh and its neighbouring areas. George Abraham Grierson, who conducted the first Linguistic Survey of India (LSI), classified Awadhi as ‘Eastern Hindi’.

In his 1971 book Evolution of Awadhi: A Branch of Hindi, Baburam Saksena described it as “the main dialect of the Eastern Hindi branch of the Indo-Aryan group of languages spoken in Northern India.”

It is spoken in Hardoi, Kheri, Faizabad (Ayodhya), Allahabad, Jaunpur, Mirzapur, Fatehpur, Agra, and Pratapgarh districts. According to Saksena, the LSI also uses the terms Purbi (eastern) and Kosali (the language of the erstwhile Kosala Kingdom, now part of present-day UP) to refer to Awadhi. Another name used for it is Baiswari, but this term is more restricted to areas including Lucknow, Unnao, Rae Bareli, and Fatehpur districts. Saksena further observes that to the west of Awadhi, the two dialects of Western Hindi spoken are Kanauji and Bundeli, while to the east, the Bihari dialect Bhojpuri is spoken. To the north, “the Awadhi area is bounded by the territory of the Nepal Government.”

He suggests that Awadhi sits between Western Hindi and Bihari. “…we find Hindi rigorous, Awadhi a little loose, while Bihari mostly does not observe the distinction of gender.”

Saksena also divides the dialects of the Awadhi-speaking regions into three categories: western (Sitapur, Lucknow, Unnao, and Fatehpur), central (Bahraich, Barabanki, and Rae Bareli), and eastern (Gonda, Ayodhya, Prayagraj, Jaunpur, and Mirzapur).

While Saksena consistently refers to Awadhi as a ‘dialect’ in his work, cultural historian Anne Murphy, who teaches at the University of British Columbia in Canada, offers a cautionary perspective: “I’d advise using the word ‘dialect’ carefully — who gets to call themselves a language and who gets to call themselves a dialect? It is a political decision.”

Upadhyay adds, “In the literary field, Awadhi is immortalised in the Ramcharitamanas (popularly known as the Ramayana) by Tulsidas,” written in 1631, likely drawing from the legendary poet Valmiki or the 13th-15th century text Adhyatma Ramayana, both originally in Sanskrit.

Upadhyay, however, cautions that people often misinterpret the Ramcharitmanas due to their limited vocabulary. He gives the example of the word Laya, which means ‘rhythm’ in general, but in Awadhi, it signifies ‘complete devastation.’ Another example is Sambhavit, which typically means ‘probable,’ but Tulsidas used it in the Awadhi sense to refer to someone who is ‘rich and influential.’ These misinterpretations, he warns, can significantly alter our understanding of the religious text.

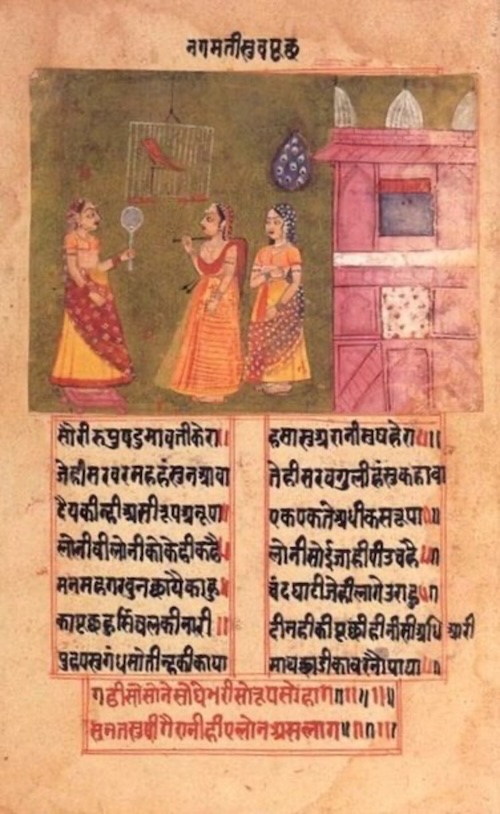

Another important literary work in Awadhi is Padmavat by Malik Muhammad Jayasi, written in 1540 AD. A romantic poem, Padmavat is notable for being written by a Muslim poet who, despite seemingly no knowledge of Sanskrit, had a command of Awadhi that, Saksena claims, was even purer than that of Tulsidas. His other known work, Akhrawat, was also in Awadhi.

“There’s also the work of poet Kabir and Hindu yogi Gorakhnath in Awadhi. I would thus compare Awadhi to a classical language, one of the oldest in north India,” notes Upadhyay. On Ayodhya’s influence on Awadhi, Upadhyay cites the example of the word ‘Kaur,’ which means “a bite” in Awadhi. He explained that ‘Kaur’ was originally a Tamil word that travelled to Ayodhya with pilgrims who flocked to the religious centre. “The pilgrims didn’t just take memories of the temple town with them; they also left behind their linguistic imprints.”

Music in the Awadh courts

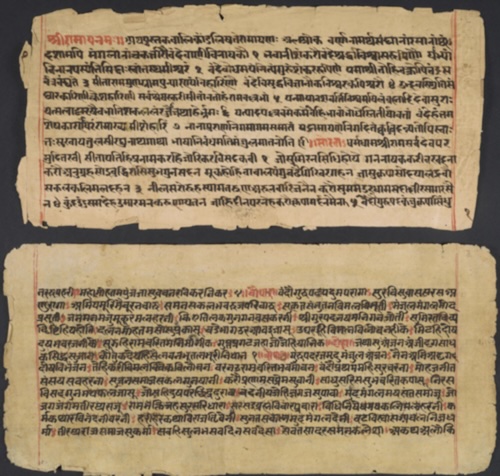

The core practices of Hindustani music have been actively performed and patronised since at least the sixteenth century across present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. This sophisticated musical tradition was deeply rooted in the court cultures of Mughal India — particularly those of Delhi and Lucknow —and was shaped by a rich corpus of theoretical writings in Sanskrit, Persian, and North Indian vernaculars such as Awadhi. It flourished under the aegis of celebrated figures such as Tansen.

Notably, Hindustani music evolved in close dialogue with the historical processes of its time. One striking example is an 1870 thumri (folk song) from Lucknow, quoted by Richard David Williams in his 2014 thesis Hindustani Music Between Awadh and Bengal, c. 1758–1905. The song captures the anguish of loss following the annexation of Awadh:

“The kingdom is drowned in the salt of the harem:

His Majesty is going to London.

His ladies are weeping in every palace:

Come to the alley, in the alley the cobbles weep.”

Composed in the aftermath of the 1857 uprising — when the British Crown formally took control of India — the song mourns the exile of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (1822-1887), who found himself in London, appealing in vain for the restoration of his kingdom. This moment of imperial rupture not only marked the end of regional sovereignty but also signaled a shift in the trajectory of Hindustani music.

The decline of aristocratic patronage gave way to new custodians. A rising elite — primarily upper-middle-class Hindu men whose families had prospered under colonial economic structures — began to sustain and reshape musical traditions.

In her article Reviving the Golden Age Again: “Classicization,” Hindustani Music, and the Mughals (2010), musical scholar Katherine Butler Schofield argues that efforts to refashion Hindustani music as ‘classical’ were, in part, strategic responses to colonial narratives. British figures such as William Jones promoted the idea that Indian music had declined from a Hindu-Sanskritic golden age, supposedly due to the ignorance of its later Muslim patrons. In response, indigenous scholars and musicians, especially in Awadh, sought to reclaim the prestige of their musical heritage in ways that could hold their own against European classical forms.

Cultural interaction, however, extended beyond critique. Anglo-Indian families affiliated with the courts of Awadh and Benares — such as the Plowdens and Fowkes — not only attended Indian music performances but also supported and occasionally patronised them. Indian elites, in turn, showed a reciprocal curiosity toward European music. The Nawabs of Awadh, for example, employed up to fifteen European musicians and piano tuners between 1775 and 1856.

Even amid political upheaval, the tradition of Indo-Persian musical scholarship remained vibrant well into the early nineteenth century, particularly at the court of Awadh.

The downfall of the ‘little people’s language’

Linguist and academic Peggy Mohan, in her book Wanderers, Kings, Merchants: The Story of India Through Its Languages (2021), observes that between the tenth and twelfth centuries, signs of ‘little people’s languages’ began to emerge. In the area around Delhi, poetry was written in Braj and Awadhi; however, a new, unnamed dialect soon developed, which eventually evolved into the language we recognise as Hindi today. In her interview with indianexpress.com, she notes, “The ‘little languages’ included Dehlavi spoken in Delhi, Braj from the Aligarh area, and Awadhi from the Awadh region.”

While she acknowledges that these languages weren’t vastly different, she also notes they weren’t directly connected. However, with the arrival of the Sultanates from Central Asia, the Dehlavi gained prominence, and over time, it flourished as the capital city’s language since 1911. “As Delhi began to grow in importance and its language followed suit… It’s not that Awadhi or Braj disappeared, but they began to be treated as dialects of Hindi, which they really weren’t,” Mohan explains.

“Over time, as the size of [Hindi’s] shadow grew, more and more of its one-time competitors found themselves relegated to being seen as just ‘dialects of Hindi,’” she writes in her book. Murphy emphasises that Awadhi was a fully developed language long before the emergence of modern Hindi. “It was established as a literary language in the 14th century, while Braj followed in the early 15th century as a literary language across North India,” she says. Labeling Awadhi a ‘dialect,’ she argues, is a political act — a fabrication. “It was only in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that languages like Awadhi and Braj were reclassified as dialects of modern Hindi.”

This shift is echoed by academic Asha Sarangi, who, in her 2009 work Language and Politics in India, writes, “The pattern of growth Hindi has followed since independence is qualitatively different from its growth during the colonial period…” While this expansion has granted Hindi a larger audience, she notes, “It seems to have lost its earlier cultural identity, wherein it was territorially confined largely to the western and some parts of eastern Uttar Pradesh and was linguistically fused with Urdu.” As a result, Hindi has evolved into a “supra-language,” overshadowing Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Marwari, etc.

This process of standardisation, as it can be called, was not unique to the North. Mohan adds, “A similar trend was happening in Bengal, where the first language to gain prominence in the Sultan’s courts eventually became what we now know as standard Bengali. But no one questioned what happened to other varieties like Chittagong Bengali [present-day Bangladesh]. It didn’t become an issue because these dialects were all seen as local variants of Bengali, while Awadhi and Braj had always had their own names.”

Mohan also highlights a unique gender stereotype associated with speaking Awadhi. Citing Saeed Naqvi’s memoir Being the Other: The Muslims in India, she explains that in his hometown of Mustafabad in western Uttar Pradesh, men spoke Urdu while women spoke Awadhi. This notion, according to Mamta Singh, still prevails: “Awadhi remains a language spoken by the women of the house,” she says.

Upadhyay discusses the impact of the Revolt of 1857 on the Awadhi language. He explains, “By the end of the 18th century, when the East India Company arrived and began recruiting, they found the men of the Awadh region to be hardworking. In fact, one-third of the entire native army of the East India Company was from Awadh.” However, the revolt in Lucknow turned the British against the region, leading them to target and persecute the Awadhi-speaking population.

“Awadhi survived in homes, and people continued speaking it privately, but 1857 effectively silenced the language in public life,” he says. While many languages were silenced during this period, he emphasises that Awadhi’s unique situation was because, with one-third of the recruits coming from other regions, the fearful population ceased speaking it altogether.

He further suggests that the returning recruits brought home a unique, hybridised form of Awadhi — Paltani Awadhi. An example was the word Safar Maine, which came from snipers and miners.

The global connection

Poonam Shukla, an Awadhi-speaking resident of Nepal, shares the global relevance of the language. “Awadhi-speaking people inhabit various parts of the world, including the Caribbean, Fiji, Guyana, Mauritius, South Africa, and Nepal due to their ancestors migrating as indentured labourers for the East India Company.” While unsure of when her family first moved, she notes that both her grandfather and father were born in Nepal.

In certain regions of southwestern Nepal, such as Lumbini and Kanchanpur, Awadhi-speaking communities dominate. Shukla attributes the language’s retention to cross-cultural marriage restrictions within the community. “Marriages happen within Awadhi-speaking families with historical ties to Awadh, ensuring the language is preserved.” Smiling, she notes, “I was never formally taught Awadhi; I learned it because my mother spoke it. When I visited my village, everyone spoke it.”

She also reflects on the social stigma around speaking Awadhi. “Growing up, whether in India or Nepal, I felt ashamed to speak my language because of its perception as dehati (slang for rural). But the narrative has changed. This is my language, my identity.” She adds, “Take Valmiki’s Ramayan, written in Sanskrit — it requires considerable scholarship to understand. That’s why Tulsidas rewrote it in Awadhi, the language of the common people. If Hindi had been the language of the masses at the time, the Ramayan would have been written in Hindi, not Awadhi.”

With similar pride, Upadhyay remarks, “I come from Awadh. I speak Awadhi, my wife speaks Awadhi, and so does our son. So, it’s not that the language isn’t being passed on. The real issue is that people no longer take pride in it.” Mohan echoes this sentiment: “In the end, it’s the parents who decide to distance their children from the language.”