Arabi Malayalam, Arwi (Arabic Tamil)

m (Pdewan moved page Arabi Malayalam to Arabi Malayalam, Arwi (Arabic Tamil) without leaving a redirect) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 8: | Line 7: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

=Arabi Malayalam= | =Arabi Malayalam= | ||

| Line 25: | Line 24: | ||

Linguistic experts said using the script for graffiti could indeed be an attempt to connect with Muslims. They also said that the graffiti has lot of spelling mistakes. | Linguistic experts said using the script for graffiti could indeed be an attempt to connect with Muslims. They also said that the graffiti has lot of spelling mistakes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Arabi Malayalam, Arwi (Arabic Tamil) | ||

| + | ==As of 2025== | ||

| + | [https://indianexpress.com/article/research/the-consciously-forgotten-worlds-of-arabic-malayalam-and-arabic-tamil-9947493/ Adrija Roychowdhury, April 21, 2025: ''The Indian Express''] | ||

| + | |||

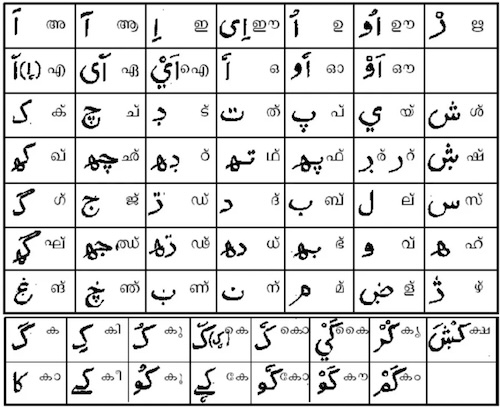

| + | [[File: The Arabic-Malayalam alphabet (Wikimedia Commons).jpg|The Arabic-Malayalam alphabet (Wikimedia Commons) <br/> From: [https://indianexpress.com/article/research/the-consciously-forgotten-worlds-of-arabic-malayalam-and-arabic-tamil-9947493/ Adrija Roychowdhury, April 21, 2025: ''The Indian Express'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: A seventeenth-century Sufi poem Bismil Kuram by Thuckalay Peer Mohammed Appa in Arabic-Tamil script from a 20th century manuscript. (Reproduced with permission from Torsten Tschacher).jpg|A seventeenth-century Sufi poem Bismil Kuram by Thuckalay Peer Mohammed Appa in Arabic-Tamil script from a 20th century manuscript. (Reproduced with permission from Torsten Tschacher) <br/> From: [https://indianexpress.com/article/research/the-consciously-forgotten-worlds-of-arabic-malayalam-and-arabic-tamil-9947493/ Adrija Roychowdhury, April 21, 2025: ''The Indian Express'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '' The Arabic script influenced several South Asian languages such as Gujarati, Bengali, Punjabi, Tamil, and Malayalam. While most of these traditions lay forgotten for decades, there have been fresh efforts in the recent past to explore and preserve two particularly major language systems — Arabic Tamil (also known as Arwi) and Arabic Malayalam. '' | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | While working at the British Library in London a few years ago, Professor Mahmood Kooria received an unusual request from the curator of the South Asia Collections, the department carrying archives, manuscripts and other historical records from India and other parts of South Asia. He had come across a large set of texts written in the Arabic script. The curator of Arabic texts was able to read them but could not comprehend the meaning. The language seemed to be Malayalam, yet the Malayalam curator couldn’t decipher them either. Kooria, who had learned ‘Arabic-Malayalam’ as a child at a madrasa in Kerala, immediately recognised both the text and the content. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Arabic-Malayalam texts in the collection, he says, were of various kinds. “From travel accounts to medicine, one can find a diverse set,” he explains “There is a detailed poem about a train accident that happened in Kerala in the early 20th century. There are also poems about the floods that happened in Kerala in 1909 and then in 1924.” One of the most unique texts he came across earlier was a Bible printed in the 20th century in Arabic-Malayalam. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Language, economy, and power intersect in fascinating ways. The Roman script, which is used to write the English language, is the writing system used for over 1700 languages across the world. Its rampant use is a product of both its economic and political weight. Several centuries ago, Arabic is known to have enjoyed a similar status, particularly in the Indian Ocean region. At least 80 languages in Africa, for instance, use the Arabic script. Collectively, they are known as Ajami, a term that means ‘foreign’ in Arabic. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As noted by African studies scholar Brenda Randolph in her paper, Introducing Ajami, the script “spread in Africa between the 10th-16th centuries with the spread of Islam and Arabic.” She draws a comparison with the Roman script that, during the Middle Ages, spread in Europe with Christianity. The Arabic script was also used to produce literature in the Spanish language in the 15th and 16th centuries, and is known as Aljamiado. In Asia, the Arabic script has been employed in regions such as Malay and Java, where such texts provide a rich resource in understanding their Islamic pasts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A similar practice can be found in South Asia as well, where the Arabic script influenced languages such as Gujarati, Bengali, Punjabi, Tamil, and Malayalam. While most of these traditions lay forgotten for decades, there have been fresh efforts in the recent past to explore and preserve two particularly major language systems — Arabic Tamil (also known as Arwi) and Arabic Malayalam. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' The spread of the Arabic script ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The origins of any language or writing system are difficult to estimate with precision. Scholars of Arabic-Tamil, however, suggest that the genesis of the script could be traced to the centuries before the rise of Islam when there were frequent contacts between the Arabian Peninsula and the Tamil-speaking region, mainly for commercial purposes. Professor KMA Ahamed Zubair, in his research paper The Rise and Decline of Arabu-Tamil Language for Tamil Muslims (2014), writes of Arab colonies being present in South India before the rise of Islam and suggests that classical Tamil literary works such as Patthu Patthu and Ettuthogai bear evidence of Arab contact with the Tamil region. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The birth of Islam in the Arabian peninsula in the seventh century, however, provided a fresh impetus to the spread of the Arabic script. Historian Ronit Ricci, in her book Islam Translated (2011), notes that texts written in the Arabic script connected Muslims across boundaries of space and culture. She refers to texts written and rewritten in local languages that were profoundly influenced and shaped by the influx of Arabic. “They helped introduce and sustain a complex web of prior texts and new interpretations that were crucial to the establishment of both local and global Islamic identities,” she writes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | That is not to say that the Arabic script was tied to religious identity alone. Historian Torsten Tschacher, who has authored the book Islam in Tamil Nadu (2001), says, “In Tamil Nadu, it is common to find the same text being written in both Tamil and Arabic scripts.” He explains that trade was a most important factor in the proliferation of the Arabic script. “At a certain point in time, in most countries around the Indian Ocean, be it in East Africa, Arabia, Iran, India, parts of Southeast Asia, the Arabic script would be used in one way or the other.”. There was a practicality involved in knowing the Arabic script, much the same way in which the Roman script came to be used later. “Let’s say one had to make a written trade contract. It would just be practical to write it in the Arabic script so that people from different parts of the Indian Ocean could read it,” Tschacher says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tschacher gives the example of Munshi Abdullah, the 18th century Malayan writer settled in Tamil Nadu. Abdullah, in his writings, described how he was forced to learn Malay, Tamil, and Arabic since learning all these languages was expected from any educated person residing in that region back then. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kooria suggests that the earliest evidence of a language being written in the Arabic script is that of Persian in the late first millennium CE. In the case of Arabic-Tamil, he says, the earliest available text is from the 15th century. “However, the practice of writing Tamil in Arabic script must have been in existence from earlier,” he says. The earliest available text in Arabic-Malayalam was from the 17th century — a panegyric Muḥy al-Dīn Māla on a 12th century Sufi saint, written by Qāḍī Muhammad of Calicut in 1607. While cataloging for the British Library, Kooria also came across Arabic script texts, which he said were either Gujarati or Sindhi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several languages in Indonesia, Malaysia, and those in the entire Swahili coast that today use the Latin script were earlier dependent on the Arabic script. “Turkish is another example. It used to have an Arabic script, but switched to the Latin script in the early 20th century,” says Kooria. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kooria believes that the popularity of the Arabic script was a mark of its political significance. “Arabic is the only other Asian language, apart from Chinese, that is recognised as a lingua franca from Asia,” he says. “The major empires like the Ottomans, Saffavids, the Mughals as well as the British, definitely played a role in popularising both the Indian Ocean trade as well as the Arabic language and script,” Kooria argues. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' The decline of the Arabic script ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite the remarkable popularity of the Arabic script, it underwent a sharp decline from the early 20th century onwards. The reduced usage of the script coincided with the emergence of social reform movements in both Kerala and Tamil Nadu in the later decades of the 19th century. “Several important personalities, including the famous Malayalam writer Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, identified Arabic-Malayalam as the ‘historical blunder’ of the Muslim community in the region,” says Kooria. Basheer believed that Arabic-Malayalam marginalised the Muslim community from engaging with the wider public sphere. “Even the several so-called reformist movements, such as the Wahhabis and the Salafis, criticised the script quite vehemently,” Kooria points out. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Such criticism was coupled with educational reforms in Kerala, which resulted in state-sponsored standardisation of spoken and written Malayalam. All this, suggests Kooria, motivated Muslims to abandon the script almost entirely and ignore texts produced in the Arabic-Malayalam tradition. Hundreds and thousands of materials were consequently destroyed both intentionally and unintentionally. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Similar developments took place in Tamil Nadu. The emergence of the Dravidian movement in the early 20th century had a similar impact on Arabic-Tamil. Tschacher explains that the Dravidian movement was not concerned about the Arabic script. “However, there was a desire for unity; all Tamil speakers, no matter what their religion, must communicate with each other. In that context, many people decided to write exclusively in the Tamil script,” he says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Even when people lost touch with the Arabic-Tamil tradition, several of the important books originally published in the script were republished in the Tamil script later in the 20th century. One would assume that in the process, the Arabic words would be translated into Tamil. “However, if you compare the translation and the original text, you realise that much of the Arabic words remain the same,” says Tschacher. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Two kinds of words are often dropped out in the translations. First are the words or paragraphs representing Sufi ideas which people might be uncomfortable with, he says. The second are the Sanskrit words, which were more commonly used in older Tamil. “For example, if in the original Arabic-Tamil text language was referred to as bhasha, in the translated version, it gets changed to the Tamil mozhi,” Tschacher says, observing how larger political developments impact linguistic changes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The standardisation of Urdu in the early 20th century as the dominant Islamic school curriculum was yet another reason for the decline of the Arabic script. The proliferation of Urdu had an impact on the Tamil Hindus’ understanding of Islam in Tamil Nadu as well, suggests Tschacher. This, he says, happened because of the political developments in the late colonial period, with the Muslim League demanding a separate homeland for Muslims. “Consequently, a lot of information about Islam was filtered from North India,” he says. He gives the example of the modern Tamil dictionary in which most Arabic words are spelt as they are pronounced in Urdu and not as they would be pronounced by the Tamil-Muslim communities. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' A new lease of life for Arabic-Malayalam ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | While the historical and socio-linguistic specificities of Arabic Tamil have been explored since the mid-20th century, it is only recently that there has been an upsurge in interest in Arabic-Malayalam. The sudden rediscovery of several manuscripts in the British Library written in Arabic-Malayalam is perhaps one of the most important factors behind the tradition finding fresh enthusiasm. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Arani Ilankuberan, the head of South Asia Collections at the British Library, recollects that she first came across this unique collection in 2016 during a shelf-clearing project. “While clearing out one of the shelves, I came across this large box labelled ‘Problems from the 1950s,’” she recalls. The box had been lying there undisturbed for several years, it seemed, and immediately sparked the interest of the curators, who put out a few images of the manuscripts on social media to find experts who might be able to comprehend them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Soon after, they were able to connect a whole network of scholars from various parts of the world to the Arabic-Malayalam connection. While Kooria was one of the first to be part of the cataloguing project that ensued, other esteemed scholars, such as Ophira Gamliel, Muhammed Khaleel, and Yasser Arafat, have done extensive work in locating, preserving, and spreading knowledge about the Arabic-Malayalam tradition. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The British Library, says Kooria, hosts the richest and largest collection in the Arabic-Malayalam literary tradition outside India. Most of them were printed between the 1870s and the 1970s and acquired by the library in several phases over the course of the century. Among the texts that Kooria has looked into, about 33 are in Arwi, one each in Malay, Sindhi, or Gujarati, and the rest in Arabic-Malayalam. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “But one also finds texts written in Arabic-Malayalam in other institutes,” suggests Kooria, giving the example of a 20th century Bible written in Arabic-Malayalam that he came across at an institution in Massachusetts, US. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Within India, particularly in Kerala, several local institutions are turning their attention towards this lost cultural corpus. Among them, the Mappila Heritage Library (MHL) in the University of Calicut and Maha Kavi Moyinkutty Vaidyar Smaraka Library and Research Centre in Kondotty have been putting a remarkable amount of effort into collecting and digitising material in the Arabic-Malayalam literary tradition. The MHL has already digitised thousands of materials and prepared a full-fledged bibliography in Malayalam. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tschacher explains that the fresh enthusiasm in Arabic-Malayalam is rooted in the desire of the educated Malayalam-speaking Muslim community to understand their history better without relying exclusively upon what the British wrote about them. A similar development, he says, happened in Tamil Nadu as well. Both Kerala and Tamil Nadu have higher Muslim literacy rates than the rest of India as per a study carried out by demographer Mahendra K. Premi in 2001 and published in 2016. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nonetheless, a much larger world of Arabic literary tradition in India remains to be explored. Tucked away perhaps in little-known archives across the subcontinent and the world, the forgotten literature in Arabic-Bengali, Gujarati, Punjabi, and more, might just open up a Pandora’s box of historical connections that give a whole new meaning to the languages of India. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:India|M | ||

| + | ARABI MALAYALAM, ARWI (ARABIC TAMIL)]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Languages-Scripts|M | ||

| + | ARABI MALAYALAM, ARWI (ARABIC TAMIL)]] | ||

Revision as of 20:34, 30 April 2025

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Arabi Malayalam

Origin and spread

Election campaign graffiti for M B Rajesh, who is the LDF candidate in Palakkad, has brought to discussion a script which had been popular in the state till a few decades ago.

The graffiti seeking vote for M B Rajesh invited flak on social media for the ‘use of Arabic for minority appeasement’. However, the script used in the graffiti was Arabi Malayalam, a variant form of the Arabic script. The script, used for written and oral communication among Muslims, has its origin that dates back to pre-Islamic period.

Sherrif Kakkuzhi Maliakkal, associate professor at University of Calicut, in a social media post stated that he learned the script at the age of four, two years before his formal education began. Stating that Arabi Malayalam was the most used script during 19th century, Maliakkal said even Chelakkodan Ayisha, the brand ambassador of Kerala’s first literacy movement, learned Arabi Malayalam before she learned Malayalam.

N K Jameel Ahamed, researcher in Arabi Malayalam, said it was absurd to term Arabi Malayalam as a language of Muslims. “Until 300 years ago, the script in the region was not accessible for all. The foreigner traders, who arrived in the state had no other option but to write down Malayalam in their own script. Arabi Malayalam is such an attempt to write Malayalam in Arabic. An Arab person may be able to read Arabi Malayalam, but, may not be able to comprehend. It eventually became popular among Muslims as they had to learn Arabic words in madrassas,” he said.

Linguistic experts said using the script for graffiti could indeed be an attempt to connect with Muslims. They also said that the graffiti has lot of spelling mistakes.

=Arabi Malayalam, Arwi (Arabic Tamil)

As of 2025

Adrija Roychowdhury, April 21, 2025: The Indian Express

From: Adrija Roychowdhury, April 21, 2025: The Indian Express

From: Adrija Roychowdhury, April 21, 2025: The Indian Express

The Arabic script influenced several South Asian languages such as Gujarati, Bengali, Punjabi, Tamil, and Malayalam. While most of these traditions lay forgotten for decades, there have been fresh efforts in the recent past to explore and preserve two particularly major language systems — Arabic Tamil (also known as Arwi) and Arabic Malayalam.

While working at the British Library in London a few years ago, Professor Mahmood Kooria received an unusual request from the curator of the South Asia Collections, the department carrying archives, manuscripts and other historical records from India and other parts of South Asia. He had come across a large set of texts written in the Arabic script. The curator of Arabic texts was able to read them but could not comprehend the meaning. The language seemed to be Malayalam, yet the Malayalam curator couldn’t decipher them either. Kooria, who had learned ‘Arabic-Malayalam’ as a child at a madrasa in Kerala, immediately recognised both the text and the content.

The Arabic-Malayalam texts in the collection, he says, were of various kinds. “From travel accounts to medicine, one can find a diverse set,” he explains “There is a detailed poem about a train accident that happened in Kerala in the early 20th century. There are also poems about the floods that happened in Kerala in 1909 and then in 1924.” One of the most unique texts he came across earlier was a Bible printed in the 20th century in Arabic-Malayalam.

Language, economy, and power intersect in fascinating ways. The Roman script, which is used to write the English language, is the writing system used for over 1700 languages across the world. Its rampant use is a product of both its economic and political weight. Several centuries ago, Arabic is known to have enjoyed a similar status, particularly in the Indian Ocean region. At least 80 languages in Africa, for instance, use the Arabic script. Collectively, they are known as Ajami, a term that means ‘foreign’ in Arabic.

As noted by African studies scholar Brenda Randolph in her paper, Introducing Ajami, the script “spread in Africa between the 10th-16th centuries with the spread of Islam and Arabic.” She draws a comparison with the Roman script that, during the Middle Ages, spread in Europe with Christianity. The Arabic script was also used to produce literature in the Spanish language in the 15th and 16th centuries, and is known as Aljamiado. In Asia, the Arabic script has been employed in regions such as Malay and Java, where such texts provide a rich resource in understanding their Islamic pasts.

A similar practice can be found in South Asia as well, where the Arabic script influenced languages such as Gujarati, Bengali, Punjabi, Tamil, and Malayalam. While most of these traditions lay forgotten for decades, there have been fresh efforts in the recent past to explore and preserve two particularly major language systems — Arabic Tamil (also known as Arwi) and Arabic Malayalam.

The spread of the Arabic script

The origins of any language or writing system are difficult to estimate with precision. Scholars of Arabic-Tamil, however, suggest that the genesis of the script could be traced to the centuries before the rise of Islam when there were frequent contacts between the Arabian Peninsula and the Tamil-speaking region, mainly for commercial purposes. Professor KMA Ahamed Zubair, in his research paper The Rise and Decline of Arabu-Tamil Language for Tamil Muslims (2014), writes of Arab colonies being present in South India before the rise of Islam and suggests that classical Tamil literary works such as Patthu Patthu and Ettuthogai bear evidence of Arab contact with the Tamil region.

The birth of Islam in the Arabian peninsula in the seventh century, however, provided a fresh impetus to the spread of the Arabic script. Historian Ronit Ricci, in her book Islam Translated (2011), notes that texts written in the Arabic script connected Muslims across boundaries of space and culture. She refers to texts written and rewritten in local languages that were profoundly influenced and shaped by the influx of Arabic. “They helped introduce and sustain a complex web of prior texts and new interpretations that were crucial to the establishment of both local and global Islamic identities,” she writes.

That is not to say that the Arabic script was tied to religious identity alone. Historian Torsten Tschacher, who has authored the book Islam in Tamil Nadu (2001), says, “In Tamil Nadu, it is common to find the same text being written in both Tamil and Arabic scripts.” He explains that trade was a most important factor in the proliferation of the Arabic script. “At a certain point in time, in most countries around the Indian Ocean, be it in East Africa, Arabia, Iran, India, parts of Southeast Asia, the Arabic script would be used in one way or the other.”. There was a practicality involved in knowing the Arabic script, much the same way in which the Roman script came to be used later. “Let’s say one had to make a written trade contract. It would just be practical to write it in the Arabic script so that people from different parts of the Indian Ocean could read it,” Tschacher says.

Tschacher gives the example of Munshi Abdullah, the 18th century Malayan writer settled in Tamil Nadu. Abdullah, in his writings, described how he was forced to learn Malay, Tamil, and Arabic since learning all these languages was expected from any educated person residing in that region back then.

Kooria suggests that the earliest evidence of a language being written in the Arabic script is that of Persian in the late first millennium CE. In the case of Arabic-Tamil, he says, the earliest available text is from the 15th century. “However, the practice of writing Tamil in Arabic script must have been in existence from earlier,” he says. The earliest available text in Arabic-Malayalam was from the 17th century — a panegyric Muḥy al-Dīn Māla on a 12th century Sufi saint, written by Qāḍī Muhammad of Calicut in 1607. While cataloging for the British Library, Kooria also came across Arabic script texts, which he said were either Gujarati or Sindhi.

Several languages in Indonesia, Malaysia, and those in the entire Swahili coast that today use the Latin script were earlier dependent on the Arabic script. “Turkish is another example. It used to have an Arabic script, but switched to the Latin script in the early 20th century,” says Kooria.

Kooria believes that the popularity of the Arabic script was a mark of its political significance. “Arabic is the only other Asian language, apart from Chinese, that is recognised as a lingua franca from Asia,” he says. “The major empires like the Ottomans, Saffavids, the Mughals as well as the British, definitely played a role in popularising both the Indian Ocean trade as well as the Arabic language and script,” Kooria argues.

The decline of the Arabic script

Despite the remarkable popularity of the Arabic script, it underwent a sharp decline from the early 20th century onwards. The reduced usage of the script coincided with the emergence of social reform movements in both Kerala and Tamil Nadu in the later decades of the 19th century. “Several important personalities, including the famous Malayalam writer Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, identified Arabic-Malayalam as the ‘historical blunder’ of the Muslim community in the region,” says Kooria. Basheer believed that Arabic-Malayalam marginalised the Muslim community from engaging with the wider public sphere. “Even the several so-called reformist movements, such as the Wahhabis and the Salafis, criticised the script quite vehemently,” Kooria points out.

Such criticism was coupled with educational reforms in Kerala, which resulted in state-sponsored standardisation of spoken and written Malayalam. All this, suggests Kooria, motivated Muslims to abandon the script almost entirely and ignore texts produced in the Arabic-Malayalam tradition. Hundreds and thousands of materials were consequently destroyed both intentionally and unintentionally.

Similar developments took place in Tamil Nadu. The emergence of the Dravidian movement in the early 20th century had a similar impact on Arabic-Tamil. Tschacher explains that the Dravidian movement was not concerned about the Arabic script. “However, there was a desire for unity; all Tamil speakers, no matter what their religion, must communicate with each other. In that context, many people decided to write exclusively in the Tamil script,” he says.

Even when people lost touch with the Arabic-Tamil tradition, several of the important books originally published in the script were republished in the Tamil script later in the 20th century. One would assume that in the process, the Arabic words would be translated into Tamil. “However, if you compare the translation and the original text, you realise that much of the Arabic words remain the same,” says Tschacher.

Two kinds of words are often dropped out in the translations. First are the words or paragraphs representing Sufi ideas which people might be uncomfortable with, he says. The second are the Sanskrit words, which were more commonly used in older Tamil. “For example, if in the original Arabic-Tamil text language was referred to as bhasha, in the translated version, it gets changed to the Tamil mozhi,” Tschacher says, observing how larger political developments impact linguistic changes.

The standardisation of Urdu in the early 20th century as the dominant Islamic school curriculum was yet another reason for the decline of the Arabic script. The proliferation of Urdu had an impact on the Tamil Hindus’ understanding of Islam in Tamil Nadu as well, suggests Tschacher. This, he says, happened because of the political developments in the late colonial period, with the Muslim League demanding a separate homeland for Muslims. “Consequently, a lot of information about Islam was filtered from North India,” he says. He gives the example of the modern Tamil dictionary in which most Arabic words are spelt as they are pronounced in Urdu and not as they would be pronounced by the Tamil-Muslim communities.

A new lease of life for Arabic-Malayalam

While the historical and socio-linguistic specificities of Arabic Tamil have been explored since the mid-20th century, it is only recently that there has been an upsurge in interest in Arabic-Malayalam. The sudden rediscovery of several manuscripts in the British Library written in Arabic-Malayalam is perhaps one of the most important factors behind the tradition finding fresh enthusiasm.

Arani Ilankuberan, the head of South Asia Collections at the British Library, recollects that she first came across this unique collection in 2016 during a shelf-clearing project. “While clearing out one of the shelves, I came across this large box labelled ‘Problems from the 1950s,’” she recalls. The box had been lying there undisturbed for several years, it seemed, and immediately sparked the interest of the curators, who put out a few images of the manuscripts on social media to find experts who might be able to comprehend them.

Soon after, they were able to connect a whole network of scholars from various parts of the world to the Arabic-Malayalam connection. While Kooria was one of the first to be part of the cataloguing project that ensued, other esteemed scholars, such as Ophira Gamliel, Muhammed Khaleel, and Yasser Arafat, have done extensive work in locating, preserving, and spreading knowledge about the Arabic-Malayalam tradition.

The British Library, says Kooria, hosts the richest and largest collection in the Arabic-Malayalam literary tradition outside India. Most of them were printed between the 1870s and the 1970s and acquired by the library in several phases over the course of the century. Among the texts that Kooria has looked into, about 33 are in Arwi, one each in Malay, Sindhi, or Gujarati, and the rest in Arabic-Malayalam.

“But one also finds texts written in Arabic-Malayalam in other institutes,” suggests Kooria, giving the example of a 20th century Bible written in Arabic-Malayalam that he came across at an institution in Massachusetts, US.

Within India, particularly in Kerala, several local institutions are turning their attention towards this lost cultural corpus. Among them, the Mappila Heritage Library (MHL) in the University of Calicut and Maha Kavi Moyinkutty Vaidyar Smaraka Library and Research Centre in Kondotty have been putting a remarkable amount of effort into collecting and digitising material in the Arabic-Malayalam literary tradition. The MHL has already digitised thousands of materials and prepared a full-fledged bibliography in Malayalam.

Tschacher explains that the fresh enthusiasm in Arabic-Malayalam is rooted in the desire of the educated Malayalam-speaking Muslim community to understand their history better without relying exclusively upon what the British wrote about them. A similar development, he says, happened in Tamil Nadu as well. Both Kerala and Tamil Nadu have higher Muslim literacy rates than the rest of India as per a study carried out by demographer Mahendra K. Premi in 2001 and published in 2016.

Nonetheless, a much larger world of Arabic literary tradition in India remains to be explored. Tucked away perhaps in little-known archives across the subcontinent and the world, the forgotten literature in Arabic-Bengali, Gujarati, Punjabi, and more, might just open up a Pandora’s box of historical connections that give a whole new meaning to the languages of India.