Indian Ocean/ Deep-sea exploration: India

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> Additional information ma...") |

Latest revision as of 06:42, 21 May 2025

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] Status

[edit] As of 2025

U Tejonmayam, April 23, 2025: The Times of India

From: U Tejonmayam, April 23, 2025: The Times of India

In early 2000s, when Isro was soaring high with its space missions, a team of oceanographers from India were diving deep into the pirate-infested waters of the Indian Ocean. Their mission: to locate hydrothermal vents spewing superhot plumes rich in cobalt, manganese, copper, zinc, gold and silver at depths of more than 3,000m.

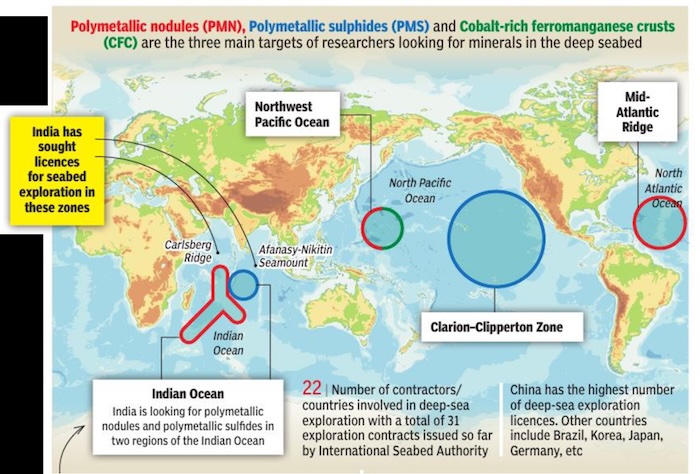

Nearly two decades later, the site known as Carlsberg Ridge, a tectonic boundary between India and Africa, is set to become India’s third deep-sea exploration zone with a licence awaited from the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an autonomous body under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that regulates all mineral-related activities on international seabeds.

India has also sought a licence to explore a fourth zone while two other probes are already underway in the depths of the Indian Ocean. So, India’s Samudrayaan mission will potentially have two oceanographers soon diving 6,000m in the Indian Ocean. Deep-ocean mining can yield minerals and metals — critical to the clean energy transition — that can be used in turbines, solar panels and electric vehicle batteries. They can also be utilised for making military weapons. India now depends on China, UK and Norway for many of these minerals and metals.

Fishing Among Pirates

The dives in the early 2000s were rudimentary. “We had chemical evidence of hydrothermal plumes in the water, but without an ROV (remotely operated vehicle) or AUV (autonomous underwater vehicle), we couldn’t physically prove anything,” said Sunil Kumar Singh, director, National Institute of Oceanography (NIO), Goa. “It was risky, too. Our ship crawled at 10 nautical miles per hour, while pirates sped around on motorboats.” Magma from the Earth’s interior that flows through the oceanic crust reacts with seawater seeping in through cracks and shoots back as hydrothermal plumes. These superheated plumes, at 300°C-350°C, carry sulphides rich in zinc, copper, manganese, cobalt, gold, silver, rare earth and platinum-group elements, which settle on the seafloor. NIO researchers have recorded temperature and chemical signatures of some of these vents.

As interest from neighbouring countries surged — Chinese researchers have captured images of mineral-rich vents in the re- gion — India in 2024 applied to ISA for an exploratory licence for two mineral-rich areas at opposite ends of the Indian Ocean. The zones in question, Carlsberg Ridge and Afanasy-Nikitin Seamount (ANS), are both rich in cobalt and manganese.

Carlsberg Ridge, the northwestern limb of the Indian Ocean Ridge system, marks the tectonic boundary where the Indian and Somalian plates drift apart. Formed nearly 30 million years ago, this seismically active ridge is between 1,800m and 3,600m deep.

Further southeast in the Central Indian Basin lies ANS, a vast region (400km x 150km) of volcanic seamounts formed 80 million years ago, a time when dinosaurs roamed the Earth. Lying 3,000km off India’s coast and named after a 15th-century Russian merchant, ANS also holds copper and nickel. Cobalt-rich crusts typically form in oxygen-rich waters, but NIO found unusually high cobalt levels between a depth of 800m and 2,000m, where oxygen is scarce. India’s application for explore this region is pending while Sri Lanka, too, has staked its claim under a different legal framework.

A Select Submersible Club

Earlier this year, researchers from National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR), headquartered in Goa, undertook a 10-hour mission using an AUV and captured the first-ever footage of an active hydrothermal vent at a depth of 3km. NCPOR director Thamban Meloth said researchers face major challenges. The seafloor topography changes suddenly and AUVs are at risk of crashing into hydrothermal vent chimneys. “Our plan is to send a tethered ROV to collect samples close to inactive vents,” he said.

In 2021, Centre approved the Deep Ocean Mission at an estimated cost of Rs 4,077 crore, making deep-sea exploration one of the seven verticals supporting India’s ambitious Blue Economy initiative. The mission, involving multiple institutions, aims to map marine biodiversity, develop complex technologies like a deep-sea mining system, and build a manned submersible, Matsya 6000, that will carry three researchers 6,000m below the surface of the Indian Ocean.

Chennai-based National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT), which is developing Matsya 6000, completed harbour trials earlier this year. The vehicle is undergoing integration and will be tested at a depth of 500m by the end of this year and at 6,000m late next year. Only the US, Russia, Japan, France and China have indigenous manned submersibles.

In Oct 2024, NIOT also tested its seabed mining system at a depth of 1,200m in the Andaman Sea. Work is on to build a powerful pumping system to lift nodules to the surface. Officials said both technologies have been developed indigenously from scratch.

“We know the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal better than anyone,” said NIOT director Balaji Ramakrishnan. “We have a proven record with our unmanned submersibles, but a manned one is a different ball game. When we are ready, our manned submersible will be among the few internationally certified vehicles.”

Eye On Ecology

The ministry of earth sciences is also building an indigenous research vessel at a Kolkata shipyard for Rs 900 crore. Designed to brave rough seas, the ship will deploy buoys and submersibles, collect samples and use seismic waves to hunt for minerals beneath the seabed.

Experts believe minerals can be extracted from the oceans with minimal ecological impact to meet future demand. Researchers are mapping biodiversity to establish a baseline for assessing environmental impact and guiding sustainable mining. One NCPOR scientist was even recognised by ISA — which is currently drafting a regulatory code for deep-sea mining in international waters — for discovering nine new species of corals, lobsters and sponges in rock samples 6km deep in central and southwest Indian Ocean.

India’s exploration also holds strategic value as China aggressively expands its ocean presence. With advanced submersibles like Jiaolong and Fendouzhe, and a fleet of research vessels, China has mapped mineral-rich zones, collected core samples, and developed cutting-edge mining technologies. ISA-granted rights have helped it dominate seabed exploration.

Meanwhile, India’s deep-sea programme has a long way to go. In the 2025-26 Budget, the ministry of earth sciences received Rs 3,649.8 crore, just a fraction of the Rs 13,416.2 crore allocated to the department of space. “We started late and have invested just a tenth of what China has in deep-sea exploration. Give us 10 years, we will be on a par with the best,” said M Ravichandran, secretary, ministry of earth sciences.

[edit] India’s Operational Ocean Probes

India already holds two licences for mineral exploration in the Indian Ocean. The first of them — obtained in 2002 and valid till 2027 — is for an area spread over a 75,000sqkm in central Indian Ocean, about 6,000 km off India’s coast and at a depth of 6km. This focus in this region is on polymetallic or manganese nodules, which are potato-shaped rocks on the seafloor packed with minerals like iron, manganese, nickel, cobalt and copper. ➤ The second licence covers 10,000sqkm at the Rodriguez Triple Junction (RTJ) near Mauritius, where three tectonic plates converge. It was signed in 2016 and is valid till 2031. This zone holds polymetallic sulphides released through hydrothermal vents rich in nickel, cobalt, zinc, copper, etc. Since the 1980s, Indian researchers have surveyed more than 3 lakh sqkm of the Indian Ocean and found nodules in half the area.

[edit] How The Ocean Bed Spews Metals

Hydrothermal vents are cracks or fissures on the ocean floor where geothermal-heated water escapes. They are commonly found near mid-ocean ridges, where tectonic plates meet.

➤ Seawater seeps into Earth’s crust through these cracks and is superheated after coming into contact with magma.

➤ The water dissolves minerals like manganese, cobalt, zinc, and precious metals. Mineral-rich water exiting the vent can reach temperatures of up to 400 degrees Celsius.

➤ Upon re-emerging and mixing with cold seawater, minerals precipitate and build chimney-like structures known as black smokers.

➤ Hydrothermal vents also support marine species, which produce food using the energy released by inorganic chemical reactions instead of photosynthesis.