Landour

(→Landour) |

(→1908) |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

cantonment contains a large school for Europeans and Eurasians, with | cantonment contains a large school for Europeans and Eurasians, with | ||

college classes. | college classes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2025== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=08_06_2025_024_003_cap_TOI Avijit Ghosh, June 8, 2025: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is no signboard outside the cemetery in Landour. It disappeared some time ago. The white-painted wooden gate, like much of the graveyard, needs upkeep; sticks have been inserted in places to keep strays out. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The Christian burial ground, just a few years younger than the cantonment town the British set up almost 200 years ago, is a testament to the forlorn side of the Raj. Many British soldiers lie buried here; young men who fell in a faraway land, not to bullets, but to malaria, cholera, and reasons unknown. Like 79299 Private JW Larvin of 19th Royal Hussars, who died at 21 in 1920. Or M Curren of the Military Police Corps, who passed on at 28 in 1918, and Private WR Goulding of King’s Dragoon Guards, who now lies surrounded by carefree daisies. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Shanta Devi lives among the dead. The caretaker’s small hut is close to the elderly, but virile, deodar tree that the Duke of Edinburgh planted in Feb 1870. Dressed in a green salwar-kurta, Shanta speaks with the quiet dignity of the hardy and the honest. Precise dates escape her. “I was born in Tehri,” she says, “and married shortly before Indira Gandhi was killed.” She was unaware that a long life in the graveyard awaited her. “My husband used to do odd jobs till he became the cemetery’s chowkidar,” she says. Then she adds, “He had breathing problems and died in 2018.” | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The unheeded resting place, ironically, is among the few spots where the soul of Landour remains intact. Even a couple of decades ago, the petite hill town, where rain and sun still wrestle everyday for dominance, personified the sensuality of silence, the importance of days without agenda. It seemed to be a place where the clock moved slower than elsewhere and where the Welsh vagabond poet WH Davies could ‘stand and stare’. Even the dogs, with their rockstar hair, would take an afternoon nap.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | The dogs are still there. The stillness is gone. There’s plenty of defence land in this hill town, perhaps a reason why fresh constructions are rare. Yet, change has crept in. Lal Tibba has lost its natural grace, replaced by a cafe that overlooks the main picture point. The view can be bought, but the place now misses innocence and serenity. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

It’s the day-trippers — too many of them — who have changed Landour. Many are holidaymakers from across the country, lodged in Mussoorie, who come here to spend a few hours. Then there are young couples, or stags, from nearby cities and states who course through town, either on motorbikes or in cars. Parked SUVs and sedans stretch from the Kellogg’s Church to over half a kilometre. Earlier, the quiet walks on the paved path ways surrounded by pine repaired and restored amblers. Now, every 30 seconds or so, automobiles rush arrogantly by. The air, once scented with nature, is awash with fumes. Undeterred by the signages to observe quiet, brash music blares from big cars. This reporter saw a woman on a video call telling her friend in Surat that she is calling from ‘Londar’. She didn’t need the mobile.

“Most tourists who climb from the sweltering corruption of the plains to Himalayan serenity lack an elementary education in social graces, civilised behaviour, respect for local culture, and drive SUVs without seemingly ever having been taught any driving etiquette,” says actor Victor Banerjee, a Landour resident since 1982. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mussoorie-born writer Stephen Alter points out that the beauty of Landour lies in its forested hillsides, mountain views and peaceful atmosphere, the last of which is now under assault. “Unfortunately, it has become an extension of Mussoorie’s Mall Road, with endless traffic jams, unruly tourists and garbage littering the slopes. Sometimes, I don’t recognise Landour anymore,” he confesses. | ||

| + |

Adds Victor, “Landour is today’s melting pot of social disgrace. We residents tolerate it behind shutters and locked gates and certainly, during weekends, never dare venture out onto the plagued hillside.”

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Unsurprisingly, a stream of vehicles is lined up on the road near Char Dukan, indicating a traffic jam ahead. They are shooting — what else! — a web series just below the 185-yearold St Paul’s Church, where the opening scene of Alter’s taut thriller, The Rataban Betrayal, is set. Movement of humans and vehicles is on pause, as happens during ‘VIP movement’ in the Capital. In New Delhi, cops perform such tasks. Here, burly men looking like pub bouncers are on the job. Only a monkey dares disobey, interrupting the romantic frame. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The simians have become bolder. Two years ago, they vigorously stalked a pack of journalists, including this reporter, carrying plum jam and peanut butter in plastic bags. The monkeys — one of them had a thuggish glint — walked alongside the group for a good 500 metres. At Char Dukan, one of them jumped, literally, on an editor’s shoulder. In another instance, a cocky simian burgled a half-eaten pizza from a shocked woman’s bag. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Over the years, Landour has attracted many notables, Sachin Tendulkar the most well-known of them. There’s a photograph of him grabbing a bite at one of those modest eating places in Char Dukan. Another photo adorned the humble shop of a cobbler in Landour’s Cantonment Bazaar who had crafted a pair of boots for the cricketer.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Landour has its own superstar, though. The stardom of Ruskin Bond, now 91, is untrammeled by age. To young literature lovers, his house is a place of pilgrimage. But fans can also be phoneys. In ‘Leaves from a Journal’, Bond writes with humour how an elderly gentleman from Saharanpur came to his home and told him how his favourite Bond story was ‘The Lamp Is Lit Again’ and that he was also aware that the writer’s father had been in the ICS. Bond gently reveals that he hadn’t written any story by that name and wasn’t aware of his father being in ICS — although he was kind enough not to point that out to the gentleman. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

What the day trippers have been unable to change is the Landour weather. The wind caressing your face is cold even in May. The drizzle remains as unexpected as before. The rhododendrons are redder than ever. And you can still pick up pine cones on a walk.

| ||

| + | Also, for its size, the hill station offers some first-rate eateries, including a couple in the pricey hotels. Hot pancakes with maple syrup remain a best-seller at Char Dukan. A new bakehouse at Sisters Bazaar is a hot favourite. Even on weekdays, the waiting time can stretch to 30 minutes or more. The butter and jam at the vintage home provisions store still draws in buyers. Meeting a young dog named Gangster sitting at the entrance is a bonus. Never was a dog more different from his name. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Tourism creates and sustains livelihoods. But Landour encapsulates the fate of many hill stations overrun by tourists. No place can be frozen in time, but picture-postcard hill towns also need to be nursed with care. Landour is slow music. It is in danger of becoming a song lost. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===‘Have learnt to live with noise of traffic’=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Anmol Jain | TNN | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Mussoorie: Landour was quiet and deserted in the 1960s and was known only as an army cantonment, recalls Ruskin Bond, celebrated author and a long-time resident. “When I first visited Landour in the 1960s, it was absolutely peaceful and tranquil. There were no tourists around,” Bond recalls.

Although the author has been residing in Mussoorie since 1964, he moved to Landour around 1979. “Landour was not regarded as a tourist destination in those days. But over the years, the popularity of the area seems to have exponentially increased,” Bond says.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | “It is good in some ways and in some ways, it is not so good,” he says philosophically. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The increase in tourist footfall, he notes, augurs well for local businesses, since a number of cafes, guest houses and home stays have come up to cater to holidayers. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

“In a way, it is good for the local businesses, but yes, it does create problems for us residents. Last week, I was coming up from Dehradun after a medical check-up and it took over an hour to reach my house from Clock Tower — the same time that it had taken us to drive up to Mussoorie from Dehradun,” he recalls. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

He adds with a chuckle that he has now learnt to cope with the new reality. “I can hear the traffic sounds from my home, but I have learnt to live with it. I do not go out much and the traffic noise does not affect my writing as I generally write in the mornings, when the tourists have not yet arrived,” he laughs. | ||

[[Category:India|LLANDOUR | [[Category:India|LLANDOUR | ||

Latest revision as of 16:38, 11 June 2025

Contents |

[edit] Landour

[edit] 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

{Landhaur). — Hill cantonment and sanitarium in Dehra Dun District, United Provinces, situated in 30° 27' N. and 78° 7' E. Population in the cold season (1901), 1,720. In September, 1900, the population was 3,711, of whom 1,516 were Christians. A con- valescent station for European soldiers was established in 1827, the year after the foundation of Mussoorie, which adjoins Landour. The cantonment contains a large school for Europeans and Eurasians, with college classes.

[edit] 2025

Avijit Ghosh, June 8, 2025: The Times of India

There is no signboard outside the cemetery in Landour. It disappeared some time ago. The white-painted wooden gate, like much of the graveyard, needs upkeep; sticks have been inserted in places to keep strays out.

The Christian burial ground, just a few years younger than the cantonment town the British set up almost 200 years ago, is a testament to the forlorn side of the Raj. Many British soldiers lie buried here; young men who fell in a faraway land, not to bullets, but to malaria, cholera, and reasons unknown. Like 79299 Private JW Larvin of 19th Royal Hussars, who died at 21 in 1920. Or M Curren of the Military Police Corps, who passed on at 28 in 1918, and Private WR Goulding of King’s Dragoon Guards, who now lies surrounded by carefree daisies.

Shanta Devi lives among the dead. The caretaker’s small hut is close to the elderly, but virile, deodar tree that the Duke of Edinburgh planted in Feb 1870. Dressed in a green salwar-kurta, Shanta speaks with the quiet dignity of the hardy and the honest. Precise dates escape her. “I was born in Tehri,” she says, “and married shortly before Indira Gandhi was killed.” She was unaware that a long life in the graveyard awaited her. “My husband used to do odd jobs till he became the cemetery’s chowkidar,” she says. Then she adds, “He had breathing problems and died in 2018.”

The unheeded resting place, ironically, is among the few spots where the soul of Landour remains intact. Even a couple of decades ago, the petite hill town, where rain and sun still wrestle everyday for dominance, personified the sensuality of silence, the importance of days without agenda. It seemed to be a place where the clock moved slower than elsewhere and where the Welsh vagabond poet WH Davies could ‘stand and stare’. Even the dogs, with their rockstar hair, would take an afternoon nap.

The dogs are still there. The stillness is gone. There’s plenty of defence land in this hill town, perhaps a reason why fresh constructions are rare. Yet, change has crept in. Lal Tibba has lost its natural grace, replaced by a cafe that overlooks the main picture point. The view can be bought, but the place now misses innocence and serenity.

It’s the day-trippers — too many of them — who have changed Landour. Many are holidaymakers from across the country, lodged in Mussoorie, who come here to spend a few hours. Then there are young couples, or stags, from nearby cities and states who course through town, either on motorbikes or in cars. Parked SUVs and sedans stretch from the Kellogg’s Church to over half a kilometre. Earlier, the quiet walks on the paved path ways surrounded by pine repaired and restored amblers. Now, every 30 seconds or so, automobiles rush arrogantly by. The air, once scented with nature, is awash with fumes. Undeterred by the signages to observe quiet, brash music blares from big cars. This reporter saw a woman on a video call telling her friend in Surat that she is calling from ‘Londar’. She didn’t need the mobile. “Most tourists who climb from the sweltering corruption of the plains to Himalayan serenity lack an elementary education in social graces, civilised behaviour, respect for local culture, and drive SUVs without seemingly ever having been taught any driving etiquette,” says actor Victor Banerjee, a Landour resident since 1982.

Mussoorie-born writer Stephen Alter points out that the beauty of Landour lies in its forested hillsides, mountain views and peaceful atmosphere, the last of which is now under assault. “Unfortunately, it has become an extension of Mussoorie’s Mall Road, with endless traffic jams, unruly tourists and garbage littering the slopes. Sometimes, I don’t recognise Landour anymore,” he confesses. Adds Victor, “Landour is today’s melting pot of social disgrace. We residents tolerate it behind shutters and locked gates and certainly, during weekends, never dare venture out onto the plagued hillside.”

Unsurprisingly, a stream of vehicles is lined up on the road near Char Dukan, indicating a traffic jam ahead. They are shooting — what else! — a web series just below the 185-yearold St Paul’s Church, where the opening scene of Alter’s taut thriller, The Rataban Betrayal, is set. Movement of humans and vehicles is on pause, as happens during ‘VIP movement’ in the Capital. In New Delhi, cops perform such tasks. Here, burly men looking like pub bouncers are on the job. Only a monkey dares disobey, interrupting the romantic frame.

The simians have become bolder. Two years ago, they vigorously stalked a pack of journalists, including this reporter, carrying plum jam and peanut butter in plastic bags. The monkeys — one of them had a thuggish glint — walked alongside the group for a good 500 metres. At Char Dukan, one of them jumped, literally, on an editor’s shoulder. In another instance, a cocky simian burgled a half-eaten pizza from a shocked woman’s bag.

Over the years, Landour has attracted many notables, Sachin Tendulkar the most well-known of them. There’s a photograph of him grabbing a bite at one of those modest eating places in Char Dukan. Another photo adorned the humble shop of a cobbler in Landour’s Cantonment Bazaar who had crafted a pair of boots for the cricketer.

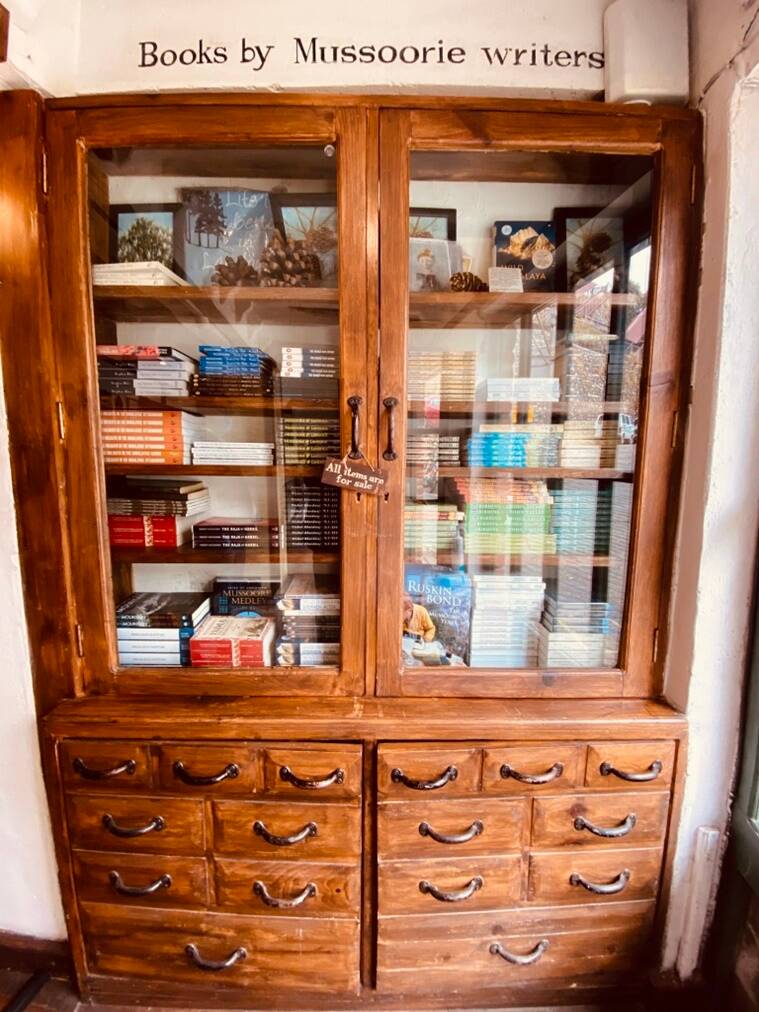

Landour has its own superstar, though. The stardom of Ruskin Bond, now 91, is untrammeled by age. To young literature lovers, his house is a place of pilgrimage. But fans can also be phoneys. In ‘Leaves from a Journal’, Bond writes with humour how an elderly gentleman from Saharanpur came to his home and told him how his favourite Bond story was ‘The Lamp Is Lit Again’ and that he was also aware that the writer’s father had been in the ICS. Bond gently reveals that he hadn’t written any story by that name and wasn’t aware of his father being in ICS — although he was kind enough not to point that out to the gentleman.

What the day trippers have been unable to change is the Landour weather. The wind caressing your face is cold even in May. The drizzle remains as unexpected as before. The rhododendrons are redder than ever. And you can still pick up pine cones on a walk. Also, for its size, the hill station offers some first-rate eateries, including a couple in the pricey hotels. Hot pancakes with maple syrup remain a best-seller at Char Dukan. A new bakehouse at Sisters Bazaar is a hot favourite. Even on weekdays, the waiting time can stretch to 30 minutes or more. The butter and jam at the vintage home provisions store still draws in buyers. Meeting a young dog named Gangster sitting at the entrance is a bonus. Never was a dog more different from his name.

Tourism creates and sustains livelihoods. But Landour encapsulates the fate of many hill stations overrun by tourists. No place can be frozen in time, but picture-postcard hill towns also need to be nursed with care. Landour is slow music. It is in danger of becoming a song lost.

[edit] ‘Have learnt to live with noise of traffic’

Anmol Jain | TNN

Mussoorie: Landour was quiet and deserted in the 1960s and was known only as an army cantonment, recalls Ruskin Bond, celebrated author and a long-time resident. “When I first visited Landour in the 1960s, it was absolutely peaceful and tranquil. There were no tourists around,” Bond recalls. Although the author has been residing in Mussoorie since 1964, he moved to Landour around 1979. “Landour was not regarded as a tourist destination in those days. But over the years, the popularity of the area seems to have exponentially increased,” Bond says.

“It is good in some ways and in some ways, it is not so good,” he says philosophically.

The increase in tourist footfall, he notes, augurs well for local businesses, since a number of cafes, guest houses and home stays have come up to cater to holidayers.

“In a way, it is good for the local businesses, but yes, it does create problems for us residents. Last week, I was coming up from Dehradun after a medical check-up and it took over an hour to reach my house from Clock Tower — the same time that it had taken us to drive up to Mussoorie from Dehradun,” he recalls.

He adds with a chuckle that he has now learnt to cope with the new reality. “I can hear the traffic sounds from my home, but I have learnt to live with it. I do not go out much and the traffic noise does not affect my writing as I generally write in the mornings, when the tourists have not yet arrived,” he laughs.

[edit] Factfile

From the archives of "The Times of India" : 2008

Nestled 1,200 feet above the more popular Mussoorie, Landour is an oasis of tranquillity. Here’s how its pine-scented environs and churchspire-dotted panorama inspired author Aravind Adiga to write a stunning debut novel, which has landed him in the Man Booker Prize 2008 longlist!

— Aravind Adiga is the Man Booker longlisted author of The White Tiger.

Located in Uttaranchal in the Himalayan foothills, Landour is the popular Musoorie’s less-explored cousin!

Best time to visit: Throughout the year

Altitude: 2,500 m

Nearest Airport/Railway Station: Dehra Dun Must-Visits: Lal Tibba, author Ruskin Bond’s House (pic below), Kempty Falls, Tibetan Temple, Cloud’s End

Quick Getaways: Mussoorie, Nag Tibba, Dhanaulti, Dehra Dun, Tiger Falls, Chakrata

[edit] Cuisine

[edit] The Landour Bakehouse

Ganesh Saili, Dec 19, 2021: The Indian Express

From: Ganesh Saili, Dec 19, 2021: The Indian Express

“Where’s the Bacon House?”

It does not matter where you happen to be. The aroma of their Christmas cake full of cinnamon, vanilla and nutmeg, wafting in the air, will drag you to the Landour Bakehouse that visitors refer to as the Bakery, the Bacon House or even the Bread House.

To those of us to whom Landour is home, we see it as our revenge upon our symbiotic twin Mussoorie’s over-crowded Kempty Falls or the Mall Road.

“One cold winter’s evening five years ago, Rakesh, who had a ration shop, called Munshi Mull Radhey Lal General & Provision Store (estd.1872), visited us,” recalls entrepreneur Sanjay Narang, who along with his gifted sister Rachna, had once set up one of Asia’s biggest on-flight catering business. “Could you rent our ration shop?” asked Rakesh.

“What on earth will we do with ration shop?” wondered the brother and sister, exchanging glances. “We could start a bakery. But there’s a limit on how much flour, sugar, milk and baking powder one could sell!” Narang remembers thinking, and adds, with a laugh, “Or so I thought!” Rakesh agreed to lower the rent. In exchange, the siblings offered him a percentage of the profits.

“Who could have predicted what was waiting to happen?” reminisces Narang. Though restoration did take time, what with the ancient lime-coated hessian ceiling sagging under the weight of a hundred years of dust, cobwebs and rat-droppings, everything changed when Rachna waved her magic wand to create the Landour Bakehouse. The rest was a piece of cake.

Over a hundred years — from 1850 to 1950 — the missionary community in India loved the hills and enjoyed a great standard of living. They certainly did not undergo any culinary hardships, as anyone reading these recipes will realise. Landour had an incredible mix of military doctors, nursing sisters, Landour Language School students, and Woodstock School parents and staff, who met at the Landour Community Book Club and exchanged international recipes.

Who knew that their recipes when put together and spiral-bound would go on to bake Landour a better place? First published in 1930, the typescript of the recipes were updated, revised and published as The Landour Cookbook, through five editions.

Landour Bakehouse is a tribute to the ingenuity and effort of these pioneers. Many of its desserts and puddings have been borrowed from The Landour Cookbook . So what’s different? You might wonder. It’s the grandstand view of the Himalaya mixed with the scent of pine trees.

Landour’s milkmen have had a tradition of watering their milk. Norman Van Rooy, an old Woodstock alumnus, who grew up at Redburn Cottage in the 1960s, tells me: “My mother brought back a lactometer from America. The solid proof, shocked the milkmen though briefly. They soon learnt to add flour to increase the density of watered milk.” Nevertheless, we are grateful to our doodhwalas, for their milk of varying textures. Without their contribution, half these dishes would not have been possible.

Our local bakers were a common sight up until the 1970s, carrying tin-trunks full of breads and confectionery; fudge, stick jaw, marzipan and meringues, on their heads. Most of them came from Ghogas, a tiny village 40 miles from Tehri; their ancestors arrived in Garhwal with the refugee prince, Sulaiman Shikoh, Dara Shikoh’s son in the summer of 1658.

As I write, Abha, the lady-of-the-house, reminds me of the cookbook’s mysterious powers, especially its tips on baking: “For leavening with baking powder or soda at 6,500 feet, reduce from four tablespoons to one at sea level. Never reduce the sugar. Use the maximum amount of eggs and increase flour by one tablespoon for every increase of 1,500 feet.

Like me, you too will learn that if you are downie, eat a brownie! For life is too short! Eat all the cake you want and wash it down with the special coffee brewed at the Landour Bakehouse.

Tips for Landour’s Christmas Cake:

Ideally, the preparation for our traditional Christmas cakes start weeks before with cake mixing, where you soak plenty of finely-chopped dried fruits and spices in a variety of alcohol. For the less adventurous, you may substitute orange juice for a citrus flavour; pineapple for a tang of sunshine and apple juice for a tilt towards a neutral flavour. If you’re using fruit juice, you will have to microwave the soaked dried fruit. Remember to add a little diced orange peel rind to avoid a bland cake.

For a good batter, one must not use too much baking powder as a cake is no cake unless it’s fluffy.

To get that dark brown colour, use dark-brown sugar. For extra moistness, use both oil and butter. Beat it all up till it’s smooth.

Bake very slowly in a pre-heated oven. Usually, at 7,000 ft in the sky, this can take up to three-and-a half hours but the result is worth waiting for.