Santhali language

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> Additional information ma...") |

Revision as of 12:12, 28 July 2025

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Digitising Santhali

As of 2025

Minati Singha, July 24, 2025: The Times of India

From: Minati Singha, July 24, 2025: The Times of India

From: Minati Singha, July 24, 2025: The Times of India

Bhubaneswar : Some of the comments underlined what many felt: the messages from President Droupadi Murmu and PM Narendra Modi were in a language they couldn’t identify. The occasion was the Santhali commemoration of Hul Johar, the 19th century rebellion of the community against their British overlords. The writing was in Ol Chiki, a script — its tireless advocates would say — whose time has come.

The greetings on June 30 from the President — herself a Santhali from Odisha — and the PM on X marked a defining moment for the tribal community and, more specifically, the band of language warriors striving to preserve Ol Chiki for future generations. Their efforts to rescue Santhali, one of India’s oldest tribal languages, from the margins of the linguistic mainstream have finally begun to bear fruit.

Once confined to oral traditions and scattered literature, Santhali was set on course for a digital makeover in 2014. It was a job that involved everybody from grassroots innovators, opensource contributors, translators and poets to coders and educators.

Away from debates and controversies regarding language formulas and linguistic chauvinism, it is a story of how people at the grassroots are harnessing the power of technology to preserve and promote an indigenous language in an age when ‘global’ languages dominate the internet and Gen Z is rapidly losing touch with local cultures and modes of expression.

A Language Electrified

Ol Chiki, the Santhali script, was devised in 1925 by Pandit Raghunath Murmu, an educator. But till a decade ago, typing in the script was nearly impossible on most devices. There was no proper Unicode support, no compatible keyboard, and minimal institutional recognition. There were attempts to create a digital presence, but those were not very effective until Ramjit Tudu decided to step in. A Santhali activist and technologist from Odisha’s Mayurbhanj, he noticed the lack of a digital Ol Chiki and took the initiative to develop language tools.

“It proved nearly impossible when I first tried typing in Ol Chiki on any device. That was 2014. There was no proper Unicode support for script on mobile phones or desktops. Hence, we couldn’t express the Santhali phonemes correctly. That frustrated me. I thought I can’t just sit back. I began researching and developed an Ol Chiki Unicode font and keyboard, which eventually led to the creation of Sohagee, a versatile Unicode font now widely used on mobile phones and desktops,” said Ramjit, a graduate in mechanical engineering. He currently serves as an assistant revenue inspector in Jashipur tehsil in Mayurbhanj.

While developing the digitial script, Ramjit also realised that he could not strengthen the presence of Santhali in the digital space single-handedly. So, he teamed up with other Santhali language activists.

Rising From Grassroots

Every day, after he finishes teaching at Kumbhir Mundi Primary School, situated in a remote village of Mayurbhanj district, Fagu Baskey travels 15km on his bike through hilly terrain to reach Bangiriposi. He needs to make that daily trip because that’s the only way he can get mobile connectivity. Once the network towers light up on his phone, the 33-year-old gets busy with his life’s mission — preserving his mother tongue, Santhali.

“Apart from teaching tribal children to read and write in Santhali in school, I am also working to digitise the language so that they never feel the need to abandon it simply because it is not available on the internet. Using technology, we are not just preserving Santhali words and the script, but keeping our identity, culture, and stories alive for posterity,” he said.

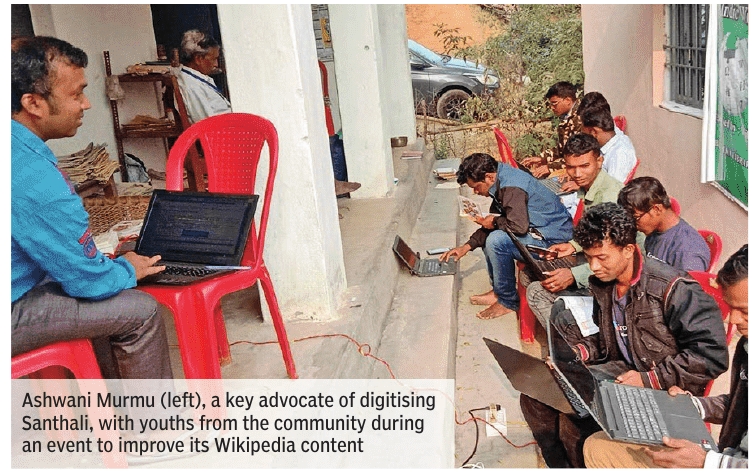

Baskey is one of the crusaders on the ground working to deepen the roots of Santhali language. But it was a movement that began with some people merely tinkering with technology. What brought structure to it was the birth of Olchikitech, a community-driven initiative co-founded by Ramjit, Ashwani Murmu and Bapi Murmu. Through this platform, the group provided technical solutions and resources for the Ol Chiki script and launched the blog ‘Olchikidr’, offering free downloads, user guides and video tutorials.

They also started Mission Ol Chiki, an outreach campaign in Santhali-speaking regions to create awareness and promote wider adoption of the technological tools powering digital Santhali.

The breakthrough moment for the language came in 2018, when Santali Wikipedia, written in Ol Chiki script, officially went live after years of dedicated editing and curation within the Wikimedia Incubator. Today, the platform hosts over 13,000 articles, making it one of the most extensive repositories of indigenous knowledge in Santhali. Dreams And Challenges Today, the Ol Chiki movement has gone beyond dictionary and encyclopaedia entries. The first online Santhali literary magazine, ‘Birmali’, now adds weight to its online presence, providing a unique platform for Santhali writers and readers from across the globe to access Ol Chiki content. “We wanted to take Santhali literature beyond print and make it accessible globally. Birmali has allowed us to connect generations, preserve oral traditions, and instil pride among Santhalispeaking youth,” said Baskey, whose poetry collection ‘Ala Saon Inj’ earned him the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar 2025. The movement has also been enriched by contributions from language activists like Prasanta Hembram, a postgraduate in life sciences, who has translated over 20 mobile and desktop apps into Santhali. He has also contributed over 6,000 bilingual sentences to the Totoeba Corpus project, strengthening AI and language learning models.

Contributors like Bijendra Hansdah and Sekhar Murmu of Jharkhand have enriched Santhali Wikipedia and Wikisource, while Bodi Baski and Ramu Hembram from Santiniketan have worked on dictionary-building projects and contributed to the launch of the Santali Wiktionary in 2025. Maina Tudu, a homemaker from Mayurbhanj, has started an online literary magazine for Santhali women. The collective contributions of the Santhali movement to Google Crowdsource, including translation, validation, and sentence collection, have led to the inclusion of Santhali in Google Translate.

“President Droupadi Murmu and Prime Minister Narendra Modi wished Santhali people in Ol Chiki script on X. The Santhali community is now printing wedding invitations in Ol Chiki script and chatting on WhatsApp using the script.

Santhali children are learning Ol Chiki beyond their medium of education and curriculum. This is the change technology has brought for the language to grow with time,” Maina said. Despite the achievements, challenges persist. “Many Santhali speakers live in areas with poor internet connectivity. Even now, lack of smartphones, digital literacy and institutional support limits our reach,” said Ramjit, whose efforts were appreciated by PM Modi in his Mann Ki Baat radio programme.

“All these tools and the presence in the digital space will be meaningless if Santhali-speaking people don’t use them in their daily life. Along with strengthening our digital presence, we are spreading awareness about the use of Santhali language and Ol Chiki in everyday work,” added Ashwani Murmu.

But what’s undeniable is that from online tutorials and open-source tools to literary forums and language corpora, the Santhali digitisation movement has come a long way. “This year, when we are celebrating the centenary of the Ol Chiki script, we are planning to launch text-tospeech and speech-to-text in the Santhali language,” Ramjit said.