Sanskrit in post-1947 India

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| + | =Literature= | ||

| + | ==1650 - 1800== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=18_10_2025_304_004_cap_TOI Naomi Canton, Oct 18, 2025: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | London : Whilst most people associate Sanskrit scholarship with the Vedas, new research by Cambridge scholars plans to show that between 1650 and 1800 a golden age of Sanskrit scholarship took place even when Britain was tightening its grip on India. Yet the erotic plays and poems, legal literature, and philosophy produced are barely known about, nor have they been translated. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The largely forgotten literary figures and their works are neglected treasures of India’s intellectual achievement, argues the research team, led by Dr Jonathan Duquette, scholar of South Asian religions at the University of Cambridge. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

“The assumption in the field was that by 1700 nothing interesting was happening in Sanskrit scholarship, but we are trying to prove that until the late 19th century, it was very vibrant, particularly in the Kaveri Delta region. For the sake of the research we had to limit our scope to those 150 years,” Duquette told TOI. | ||

| + |

Hundreds of pandits dispersed across the Indian countryside in Brahmin settlements (agrahara) and monasteries (matha) kept writing poems, plays, philosophy, theology, and legal texts in Sanskrit even when Britain tightened its grip on India.

In 1799, when the East India Company took control of the court of Thanjavur — the heart of Sanskrit patronage then — English-speaking schools began to spread. Gradually fewer Brahmin families aimed for their sons to become priests and instead sent them to the new, Western-influenced, schools.

“This could have suffocated Sanskrit scholarship very quickly but it survived partly because of these rural settlements,” Duquette said. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Awarded a five-year grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, they are leading the first extensive survey of sites in the Kaveri Delta, where the pandits were most concentrated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He and his research team, which includes Indian scholars, are particularly interested in the village of Thiruvisanallur on the banks of the river Kaveri, which Duquette has visited. This village was founded on land that had been donated by Maratha military leader Shahaji Bhonsle, father of Chhatrapati Shiva ji, to a group of 45 distinguished scholars.

Among them was revered Hindu saint Sridhara Venkatesa “Ayyaval”, a crucial early figure in the development of namasiddhanta (a spiritual doctrine that emphasises the chanting of the name of God). | ||

| + | |||

| + |

“For decades these scholars worked together and produced amazing Sanskrit scholarship. Some of the works have been printed in Sanskrit but most of these works exist only in a manuscript form. Some are in the Saraswathi Mahal Library in Thanjavur but are hard to access. Others are thought to be in local temple libraries, private libraries and with descendants of the pandits,” Duquette said.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Most Brahmins have moved away and many buildings have been sold, but some descendants remain. “We want to understand the importance of these sites and lives, and make this common knowledge,” he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The native tongues of these scholars was Tamil but they wrote in Sanskrit, so we are interested in the relationship between these Sanskrit works and Tamil works and Tamil institutions. We are not just translating words but will try to show that these villages were important centres of production of Sanskrit scholarship. There were literary geniuses among these men but many people in India don’t know them,” Duquette said. | ||

=Places where Sanskrit is spoken= | =Places where Sanskrit is spoken= | ||

| Line 137: | Line 157: | ||

SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA]] | SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA]] | ||

[[Category:Languages-Scripts|S SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA | [[Category:Languages-Scripts|S SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA | ||

| + | SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Education|S SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIASANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA | ||

| + | SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|S SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIASANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA | ||

| + | SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Languages-Scripts|S SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIASANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA | ||

SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA]] | SANSKRIT IN POST-1947 INDIA]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:12, 20 November 2025

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] Literature

[edit] 1650 - 1800

Naomi Canton, Oct 18, 2025: The Times of India

London : Whilst most people associate Sanskrit scholarship with the Vedas, new research by Cambridge scholars plans to show that between 1650 and 1800 a golden age of Sanskrit scholarship took place even when Britain was tightening its grip on India. Yet the erotic plays and poems, legal literature, and philosophy produced are barely known about, nor have they been translated.

The largely forgotten literary figures and their works are neglected treasures of India’s intellectual achievement, argues the research team, led by Dr Jonathan Duquette, scholar of South Asian religions at the University of Cambridge.

“The assumption in the field was that by 1700 nothing interesting was happening in Sanskrit scholarship, but we are trying to prove that until the late 19th century, it was very vibrant, particularly in the Kaveri Delta region. For the sake of the research we had to limit our scope to those 150 years,” Duquette told TOI. Hundreds of pandits dispersed across the Indian countryside in Brahmin settlements (agrahara) and monasteries (matha) kept writing poems, plays, philosophy, theology, and legal texts in Sanskrit even when Britain tightened its grip on India. In 1799, when the East India Company took control of the court of Thanjavur — the heart of Sanskrit patronage then — English-speaking schools began to spread. Gradually fewer Brahmin families aimed for their sons to become priests and instead sent them to the new, Western-influenced, schools. “This could have suffocated Sanskrit scholarship very quickly but it survived partly because of these rural settlements,” Duquette said.

Awarded a five-year grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, they are leading the first extensive survey of sites in the Kaveri Delta, where the pandits were most concentrated.

He and his research team, which includes Indian scholars, are particularly interested in the village of Thiruvisanallur on the banks of the river Kaveri, which Duquette has visited. This village was founded on land that had been donated by Maratha military leader Shahaji Bhonsle, father of Chhatrapati Shiva ji, to a group of 45 distinguished scholars. Among them was revered Hindu saint Sridhara Venkatesa “Ayyaval”, a crucial early figure in the development of namasiddhanta (a spiritual doctrine that emphasises the chanting of the name of God).

“For decades these scholars worked together and produced amazing Sanskrit scholarship. Some of the works have been printed in Sanskrit but most of these works exist only in a manuscript form. Some are in the Saraswathi Mahal Library in Thanjavur but are hard to access. Others are thought to be in local temple libraries, private libraries and with descendants of the pandits,” Duquette said.

Most Brahmins have moved away and many buildings have been sold, but some descendants remain. “We want to understand the importance of these sites and lives, and make this common knowledge,” he said. “The native tongues of these scholars was Tamil but they wrote in Sanskrit, so we are interested in the relationship between these Sanskrit works and Tamil works and Tamil institutions. We are not just translating words but will try to show that these villages were important centres of production of Sanskrit scholarship. There were literary geniuses among these men but many people in India don’t know them,” Duquette said.

[edit] Places where Sanskrit is spoken

[edit] Assam: Anipur Basti, Patiala Basti, 2024

Dhrubajyoti Malakar, Nov 10, 2024: The Times of India

Guwahati : “Ek kilo parimitam alookam dadatu,” requested Amalendu, a villager in Patiala Basti, asking for a kilogram of potatoes. Shopkeeper Akbar responded:“Astu dadami (take it).”

This exchange, a scene from daily life, is just one of many where Sanskrit has become an integral part of communication in Anipur Basti and Patiala Basti near the Bangladesh border in southern Assam’s Karimganj — a Muslim-majority district where the official language is Assamese and the native tongue is Bengali.

Here, the 5,000-year-old language is not just a subject in textbooks but a language spoken fluently in everyday li- fe. Villagers greet each other with a friendly “namaskaram” while callers exchange, “Bhavan katham asti (How are you)?” to which the reply is, “Samyak asmi(I am fine).”

Patiala is also witnessing a revival, with at least 50 residents fluent in Sanskrit.

Concentration levels of kids up since Sanskrit shift, say locals

Around 300 of the 400 residents of Anipur Basti converse comfortably in Sanskrit, conducting business and even personal calls in the ancient language.

Suman Kumar Nath, a local school teacher and resident of Anipur, i s proud of the village’s linguistic journey. “Being the oldest language of the country, Sanskrit is a very rich language and a reservoir of our ancient knowledge,” he said.

For Nath, Sanskrit is not only a way to honour heritage but a means of accessing the knowledge embedded in the language. Nath’s school, which educates 200 children, including 20 Muslim students, teaches all students to converse in Sanskrit. From Classes 1 to 10, every child learns Sanskrit.

The revival began about nine years ago, when villagers attended workshops and educational programmes aimed at reintegrating Sanskrit into daily life. The benefits of learning Sanskrit have been noticeable, particularly in education. Patiala Basti resident Dipan Nath said that adopting Sanskrit has positively impacted students’ performance. “Since using the language, the concentration level of the students has increased, and they have performed well in academics,” he explained.

He attributed this to Sanskrit’s extensive vocabulary, which allows villagers to answer questions concisely, often in a single word.

The resurgence has drawn the attention of academics and language experts. Dr Sudeshna Bhattacharya, head of Sanskrit department at Gauhati University, visited Patiala Basti and was amazed by what she saw. “Though many tend to label Sanskrit a ‘dead language’, the villagers, including those without formal education, have been doing commendable work by using it in their life,” she said. Bhattacharya recalled her visit to the village, where a woman without formal schooling welcomed her in fluent Sanskrit. “It was a powerful moment,” she said.

[edit] Sanskrit education

[edit] Muslim scholars, teachers/ 2019

Mohammed Wajihuddin, Nov 19, 2019: The Times of India

The students of Banaras Hindu University who are protesting against Dr Feroz Khan’s appointment as Sanskrit teacher because “a Muslim can’t teach Sanskrit” should meet Pandit Ghulam Dastagir Birajdar.

The 85-year-old Mumbaikar, former general secretary of Vishwa Sanskrit Pratisthan in Varanasi, and presently chairman of the committee to prepare school textbooks for Sanskrit in Maharashtra, has such command over the language that he is often asked by Hindus to solemnise marriages, preside over pujas or perform last rites. Even though he declines such requests, he has taught many Hindus to perform Hindu rituals.

“All my life I have promoted Sanskrit and taught it at different places, including at BHU where I have delivered many lectures. Nobody ever told me that Muslims should not teach it,” says a shocked Birajdar on telephone from Pune where he is attending a textbook committee meeting. “On the contrary, big scholars of Sanskrit admire and applaud me for my love for the ancient language.”

A certified pandit who also received a citation from former President Dr K R Narayanan, Birajdar is among several Muslims in India who have bucked the trend and studied and taught Sanskrit. To them, the Vedic principle ‘Ekam brahma dutia nasti’ (God is one and there is none except Him) is the truth also enshrined in the Quranic declaration of ‘La illaha illallah’ (there is no God but God). Bitten by the civil services bug, Dr Meraj Ahmed Khan had studied Sanskrit in college and university, topping Patna University in both BA and MA. Today, this son of a police inspector is an associate professor of Sanskrit at Kashmir University.

“What we teach in universities is modern Sanskrit which has nothing to do with religion,” says Khan, adding that he was never discriminated against for being a Muslim scholar of Sanskrit. “If they did, they wouldn’t award me a gold medal in MA.”

Some scholars say more and more Muslims are learning Sanskrit as they have an urge to understand Indian civilisation. “Since the original sources to understand India’s cultural heritage is in Sanskrit, many Muslims learn it. More than 50% of students in our department are Muslims. There has been no discrimination in appointment of teachers here,” says Dr Khalid Bin Yusuf, a former head of Sanskrit at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). “My Muslim students are teaching at different universities.”

AMU Sanskrit department’s chairman, Prof Mohammed Shareef, says Sanskrit is perceived as a “scoring” subject for UPSC exams and, hence, the interest. “If they don’t qualify in UPSC, there is always the chance to become a teacher,” says Shareef, one of the first Muslims to have received a DLitt in Sanskrit (from Allahabad University). “No one has a divine right on learning any language.”

Many Muslims also learn Sanskrit because they want to use the knowledge of it to bring Islam and Hinduism closer through comparative studies of the Quran and Hindu scriptures. Dr Mohammed Haneef Khan Shastri says former President Dr Shankar Dayal Sharma was so impressed with his Sanskrit that he gave him the title of Shastri. He retired as associate professor from Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan in Delhi in 2016.

Shastri says he wanted to find the commonalities between Sanatan Dharma’s books (Vedas, Upanishads, Bhagvad Gita) and the Quran and Hadith (sayings of Prophet Muhammad).

“If I had not studied Sanskrit, I would not have truly understood and appreciated the meaning of vasudhaiva kutumbkum (entire world is a family). The Prophet also said that there should be no discrimination among people on the basis of colour and creed,” says Khan, whose PhD is on the comparative study of the Quranic verse Surah Fateha and the Rig Veda’s revered Gayatri Mantra.

Shastri says it’s unfortunate that some think it’s their birthright to study Sanskrit. “It is the same mindset which is at work in the protest against Feroz Khan.”

[edit] 'I may be Muslim, but why can't I teach Sanskrit’

Nov 24, 2019: The Times of India

Firoz Khan's grandfather Gafur Khan in Rajasthan would sing bhajans to swaying Hindu crowds. His father Ramjan Khan studied Sanskrit would often preach on the need to look after cows in Jaipur's Bagru village.

"We had no problems then," said Khan. That's until he reached BHU as a professor to teach Sanskrit. Students from the department erupted in revolt. "A Muslim can't teach us Sanskrit," they said and sat in protest on November 7. "This isn't what Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya (who helped set up BHU) would have wanted," others raged as Khan was appointed assistant professor in the literature department of Sanskrit Vidya Dharm Vigyan.

The students remain adamant even after the administration made it clear that the selection committee had unanimously recommended the selection of Khan "on the basis of prescribed UGC guidelines and BHU Act".

“Since my childhood, till completion of my studies at Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan, I never faced any discrimination because of my religion," Khan told TOI recently. "But this is so disheartening. A group of students don't want me to teach them Sanskrit because I am not a Hindu.”

Ironically, the controversy has convulsed a city that has given at least two Muslim Sanskrit scholars who were honoured with the Padma awards in recent years -- Dr Mohammad Hanif Khan Shastri, who retired as professor at Varanasi's Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan, and Naheed Abidi of Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith.

Sriram Puranik, one of the students leading the tirade against Khan, said, "This appointment has been made as part of a conspiracy. The whole process, including the interview, was rigged ... Secondly, the stone inscription installed in BHU states very clearly that no non-Hindu can either study or teach in our department. Then why was a Muslim professor appointed?” BHU maintains there is no stone inscription on the campus that says non-Hindus can’t study or teach in the university.

[edit] In Gujarat, to Sanskrit with love

Nov 24, 2019: The Times of India

In the narrow by-lanes of minority-dominated Yakutpura area in Vadodara, several Muslim students chant Sanskrit shlokas in their classes every morning. Their teacher is 46-tear-old Aabid Saiyad who for the last 22 years has been teaching at the MES Boys’s High School. But unlike Firoz Khan, who is facing bitter protests over his appointment in BHU, Saiyed has never faced resistance - neither from Hindus nor his own community.

Saiyad firmly believes that religion and faith can’t be an impediment to imparting knowledge. “Knowledge can be imparted by anybody and who teaches is not important until it is imparted in the right way. A non-Muslim too should be able to teach Arabic and vice-versa. Language is to be taught as a language,” said Saiyad, an MA in Sanskrit and English from Vallabh Vidyanagar-based Sardar Patel University.

From a handful of pupils opting for the ancient language in 1998, he says there are 166 students in Class IX, almost all of them Muslims, who are learning Sanskrit. He urges youngsters to follow the moral teachings imbibed in the language to enrich their lives.

In fact, Saiyad’s daughter Izma Banu, a first-year student of MBBS at Baroda Medical College, had not only topped in her Class X exams in 2017, but also scored the highest in Sanskrit with 98% marks.

Prashant Rupera

[edit] Uttarakhand

[edit] 2nd official language but few students/ 2018

From: Prashant Jha, Why Sanskrit schools are dying in the land where it’s an official language, November 17, 2018: The Times of India

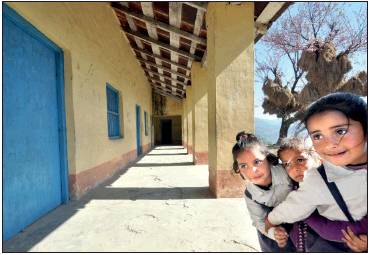

Mukhem is a small village in the picturesque Tehri Garhwal district of Uttarakhand that is famous for two things — an ancient Nagaraja temple dedicated to the king of snakes, and a Sanskrit school established by the erstwhile maharaja of Tehri almost 80 years ago that was subsequently taken over by the state government. While the biennial fair held to honour Nagaraja still attracts thousands of devotees, the Rajkiya Sanskrit Vidyalaya is in a shambles and has not seen students for almost a decade.

But that’s the story with Sanskrit schools everywhere in the state, the only one in India to have declared Sanskrit as its second official language. According to records surveyed by TOI, as many as 54 of these schools do not have principals and 13 are without a single teacher. Of the approximately 350 sanctioned posts for teachers in these schools, 189 have been vacant for years.

With 90 such institutions, Uttarakhand has one of the highest numbers of Sanskrit schools in the country. An official in the state education department blamed “lack of opportunities” for the poor state of Sanskrit education. “Students have little scope after they pass out. Either they become priests or teachers. The government is also not hiring Sanskrit teachers, so their future remains bleak.” Many question the intent of the government in not appointing teachers to fill the vacancies. “For almost a decade now, even an independent director of Sanskrit education has not been appointed,” said Manoj Sharma, a Sanskrit teacher.

Old-timers in Mukhem said the Sanskrit school was one of four set up by the maharaja to ensure that the language lived. “After the government took over the school, no teacher was appointed here for several years, resulting in students dropping out,” said Nagendra Dutt Semwal, 75, a former priest of Nagaraja temple.

Villagers said things took a downward turn after 2006, when the school’s Sanskrit teacher left. Two years later, said the school’s caretaker Dwarika Prasad, two Hindi teachers were appointed in his place. “How could Hindi teachers have taught Sanskrit?” one villagers asked.

The school at present has no teachers and no students. And, while the principal of a local college has been given additional charge of the school, according to caretaker Prasad, he has “not visited the school even once”.

Meanwhile, the state government continues to spend almost Rs 4 lakh on the school annually in terms of the caretaker’s salary and the school’s maintenance.

Despite the sorry state of affairs, the Uttarakhand government recently announced that it will open nine more Sanskrit schools, two of which will be run in association with yoga guru Ramdev’s Patanjali group. Whether associating with the yoga guru will in any way bolster the state of Sanskrit schools is something only time can tell.