Konark

(→=A 21st century overview) |

(→Konarak, 1908) |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

Internal Transport: Taxies, Auto Rickshaws and Cycle Rickshaws. | Internal Transport: Taxies, Auto Rickshaws and Cycle Rickshaws. | ||

| − | [ | + | =Jagamohan assembly hall= |

| − | + | ==2025== | |

| − | [[ | + | [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=09_12_2025_026_001_cap_TOI Diana.Sahu, December 9, 2025: ''The Times of India''] |

| − | + | ||

| − | [ | + | [[File: The Jagamohan assembly hall at Sun Temple in Konark.jpg|The Jagamohan assembly hall at Sun Temple in Konark <br/> From: [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=09_12_2025_026_001_cap_TOI Diana.Sahu, December 9, 2025: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] |

| − | + | ||

| + | Bhubaneswar: Drums once thundered beneath its vast stone roof. Priests moved through shafts of light. The Jagamohan — the grand assembly hall of the 13th-century Sun Temple in Konark — was built to hold the living pulse of a kingdom. Today, the same sacred chamber lies entombed in silence, its interior packed with tonnes of sand that kept the hall standing — and hidden — for 122 years. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

This weekend, Archaeological Survey of India pierced that silence. Engineers began drilling a narrow hole into the western wall of the Jagamohan — the first physical breach in the sand-filled chamber since the British packed it tight and sealed it shut in 1903. The drilling marks a decisive step in a long-debated plan to remove the sand and reveal what years of hidden damp and pressure may have done to one of India’s most celebrated works of sacred architecture — rising from the edge of the Bay of Bengal in Odisha’s Puri district. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The hole is being drilled between the first and second pidha — the stepped horizontal tiers — on the western wall. It is the exact point where colonial engineers once poured sand into the collapsing hall under orders from Sir John Woodburn, then lieutenant governor of Bengal, fearing the structure would otherwise crumble.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | The move comes five years after then Union culture minister Prahlad Singh Patel directed the agency to remove the sand to assess internal damage. Over that period, ASI built a special platform, designed to let experts extract sand without destabilising the monument. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

An ASI official said the current phase involves core drilling to test the hidden strength of the wall before any large-scale excavation begins. “The next step will be to create a pocket or a frame through which a tunnel will be dug out to remove the sand. This is a preliminary assessment of the wall because there are no records about its condition and stability,” the official said.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | The operation revisits fears that first surfaced nearly 70 years ago. In the mid-1950s, former ASI director general Dr Debala Mitra had carried out exploratory work inside the sealed hall. Her studies revealed that rainwater seeping into the closed interior had triggered the growth of harmful moss due to persistent dampness. That moisture was accelerating the decomposition of the khondalite stone that forms the backbone of the monument, she had said.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Those warnings were confirmed in 2019, when the Roorkee-based Central Building Research Institute examined the structure. Its report found that the sand inside the Jagamohan had settled by nearly 12ft, and that stone blocks from the upper portion of the hall were already dislodging and falling — a sign of invisible stress building within the sealed core.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Designed as a colossal stone chariot for the sun god, Surya, complete with 24 carved wheels and seven horses, the temple once served as a centre of ritual, astronomy and royal power. Over centuries, cyclones, salt-laden winds, shifting sands and rising coastal moisture linked to climate change have eaten into its surfaces, turning conservation into a perpetual race against time. | ||

| + |

What lies inside this Unesco World Heritage Site remains an open question: intact carvings preserved in darkness, or stone reduced to powder by decades of damp. | ||

[[Category:India|K KONARKKONARK | [[Category:India|K KONARKKONARK | ||

Latest revision as of 11:35, 21 December 2025

Additional information may please be sent as messages to the |

Contents |

[edit] Konarak, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Ruined temple in the head-quarters subdivision of Purl District, Bengal, situated in 19 degree 53' N. and 86° 6' E., about ii miles from the sea and 2 1 miles east of Purl town. The temple was built and dedicated to the Sun-god by Narasingha Deva I of the Ganga dynasty of Orissa, who ruled from 1238 to 1264. Konakona appears to have been the ancient name, and the modern name thus stands for Konarka, meaning ' the arka (Sun-god) at Kona.' It con- sisted of a tower, probably a little over 180 feet in height, and of a porch or mandap in front of it, about 140 feet high. The principal gate was to the east, and was flanked by the figures of two lions, mounted upon elephants. The northern and southern gates were sculptured with the figures of two elephants, each lifting up a man with his trunk, and of two horses, richly caparisoned and led by warriors. Each gate was faced by exquisite chlorite carvings, of which those of the eastern gate are still in perfect preservation. Above this gate was an enormous chlorite slab, bearing the figures of the nine planets, which is now lying a little distance from the temple and has become an object of local worship ; and above this slab there was originally a statue of the Sun- god, seated cross-legged in a niche.

Along the plinth are eight wheels

and seven horses, carved in the stone, the temple being represented as

the car of the Sun-god drawn by his seven chargers. East of the

mandafi, or porch, stands a fine square building with four pillars inside,

which evidently was used as a dancing-hall, as the carvings on its

walls all represent dancing-girls and musicians. The wall of the

courtyard measures about 500 by 300 feet ; and it originally contained

a number of smaller shrines and out-houses, of which only the remains

can now be traced. The entire courtyard till recently was filled with

sand ; but since 1902 Government has carried on systematic excava-

tions, which have brought to light many hidden parts of the temple

itself and of other structures.

The great tower of the temple collapsed long ago, and at the present day forms a huge heap of debris west of the porch ; but it is believed that about one-third of it will be found intact below the broken stones, as soon as they have been removed. In order to preserve the porch, it has been filled up with broken stones and sand, and is now entirely closed from view ; its interior was plain and of little interest. In spite of its ruinous state, the temple still forms one of the most glorious examples of Hindu architecture. Even the fact that many of the carvings around its walls are repulsive to European notions of decency cannot detract from the beauty of an edifice of which Abul Fazl said that ' even those whose judgement is critical and who are difficult to please, stood astonished at its sight.'

[Rajendralala Mitra, The Antiquities of Orissa (Calcutta, 1875, 1880); and the Reports of the Archaeological Survey of India for 1902-3 and 1903-4 (Calcutta, 1904, 1906).]

[edit] A 21st century overview

The magnificent Sun Temple at Konark is the culmination of Odishan temple architecture, and one of the most stunning monuments of religious architecture in the world. The poet Rabindranath Tagore said of Konark that 'here the language of stone surpasses the language of man', and it is true that the experience of Konark is impossible to translate into words.

The massive structure, now in ruins, sits in solitary splendour surrounded by drifting sand. Today it is located two kilometers from the sea, but originally the ocean came almost up to its base. Until fairly recent times, in fact, the temple was close enough to the shore to be used as a navigational point by European sailors, who referred to it as the 'Black Pagoda'.

Built by King Narasimhadeva in the thirteenth century, the entire temple was designed in the shape of a colossal chariot, carrying the sun god, Surya, across the heavens. Surya has been a popular deity in India since the Vedic period and the following passages occur in a prayer to him in the Rig Veda, the earliest of sacred religious text:

"Aloft his beams now bring the good, Who knows all creatures that are born, That all may look upon the Sun. The seven bay mares that draw thy car, Bring thee to us, far-seeing good, O Surya of the gleaming hair. Athwart in darkness gazing up, to him the higher light, we now Have soared to Surya, the god Among gods, the highest light."

So the image of the sun god traversing the heavens in his divine chariot, drawn by seven horses, is an ancient one. It is an image, in fact, which came to India with the Aryans, and its original Babylonian and Iranian source is echoed in the boots that Surya images, alone among Indian deities, always wear.

The idea of building an entire temple in the shape of a chariot, however, is not an ancient one, and, indeed, was a breathtakingly creative concept. Equally breathtaking was the scale of the temple which even today, in its ruined state, makes one gasp at first sight. Construction of the huge edifice is said to have taken 12 years revenues of the kingdom.

The main tower, which is now collapsed, originally followed the same general form as the towers of the Lingaraja and Jagannath temples. Its height, however, exceeded both of them, soaring to 227 feet. The jagmohana (porch) structure itself exceeded 120 feet in height. Both tower and porch are built on high platforms, around which are the 24 giant stone wheels of the chariot. The wheels are exquisite, and in themselves provide eloquent testimony to the genius of Odisha's sculptural tradition.

At the base of the collapsed tower were three subsidiary shrines, which had steps leading to the Surya images. The third major component of the temple complex was the detached natamandira (hall of dance), which remains in front of the temple. Of the 22 subsidiary temples which once stood within the enclosure, two remain (to the west of the tower): the Vaishnava Temple and the Mayadevi Temple. At either side of the main temple are colossal figures of royal elephants and royal horses.

Just why this amazing structure was built here is a mystery. Konark was an important port from early times, and was known to the geographer Ptolemy in the second century AD. A popular legend explains that one son of the god Krishna, the vain and handsome Samba, once ridiculed a holy, although ugly, sage. The sage took his revenge by luring Samba to a pool where Krishna's consorts were bathing. While Samba stared, the sage slipped away and summoned Krishna to the site. Enraged by his son's seeming impropriety with his stepmothers, Krishna cursed the boy with leprosy. Later he realized that Samba had been tricked, but it was too late to withdraw the curse. Samba then travelled to the seashore, where he performed 12 years penance to Surya who, pleased with his devotion, cured him of the dreaded disease. In thanksgiving, Samba erected a temple at the spot.

In India, history and legend are often intextricably mixed. Scholars however feel that Narasimhadeva, the historical builder of the temple, probably erected the temple as a victory monument, after a successful campaign against Muslim invaders.

In any case, the temple which Narasimhadeva left us is a chronicle in stone of the religious, military, social, and domestic aspects of his thirteenth century royal world. Every inch of the remaining portions of the temple is covered with sculpture of an unsurpassed beauty and grace, in tableaux and freestanding pieces ranging from the monumental to the miniature. The subject matter is fascinating. Thousands of images include deities, celestial and human musicians, dancers, lovers, and myriad scenes of courtly life, ranging from hunts and military battles to the pleasures of courtly relaxation. These are interspersed with birds, animals (close to two thousand charming and lively elephants march around the base of the main temple alone), mythological creatures, and a wealth of intricate botanical and geometrical decorative designs.

The famous jewel-like quality of Odishan art is evident throughout, as is a very human perspective which makes the sculpture extremely accessible. The temple is famous for its erotic sculptures, which can be found primarily on the second level of the porch structure. The possible meaning of these images has been discussed elsewhere in this book. It will become immediately apparent upon viewing them that the frank nature of their content is combined with an overwhelming tenderness and lyrical movement. This same kindly and indulgent view of life extends to almost all the other sculptures at Konark, where the thousands of human, animal, and divine personages are shown engaged in the full range of the 'carnival of life' with an overwhelming sense of appealing realism.

The only images, in fact, which do not share this relaxed air of accessibility are the three main images of Surya on the northern, western, and southern facades of the temple tower. Carved in an almost metallic green chlorite stone (in contrast to the soft weathered khondalite of the rest of the structure), these huge images stand in a formal frontal position which is often used to portray divinities in a state of spiritual equilibrium. Although their dignity sets them apart from the rest of the sculptures, it is, nevertheless, a benevolent dignity, and one which does not include any trace of the aloof or the cold. Konark has been called one of the last Indian temples in which a living tradition was at work, the 'brightest flame of a dying lamp'. As we gaze at these superb images of Surya benevolently reigning over his exquisite stone world, we cannot help but feel that the passing of the tradition has been nothing short of tragic.

[edit] How to Reach

By Air - Nearest Airport is Bhubaneswar- 65 kms.

By Rail - Nearest railway station is Bhubaneswar 65 kms. And Puri 35 kms.

By Road - Connected by National Hithway from Bhubaneswar – 65 kms. Via Pipili and Puri (35 kms.) on Marine Drive. There are frequent and regular bus service from Bhubaneswar and Puri in addition to conducted tour services by OTDC.

Internal Transport: Taxies, Auto Rickshaws and Cycle Rickshaws.

[edit] Jagamohan assembly hall

[edit] 2025

Diana.Sahu, December 9, 2025: The Times of India

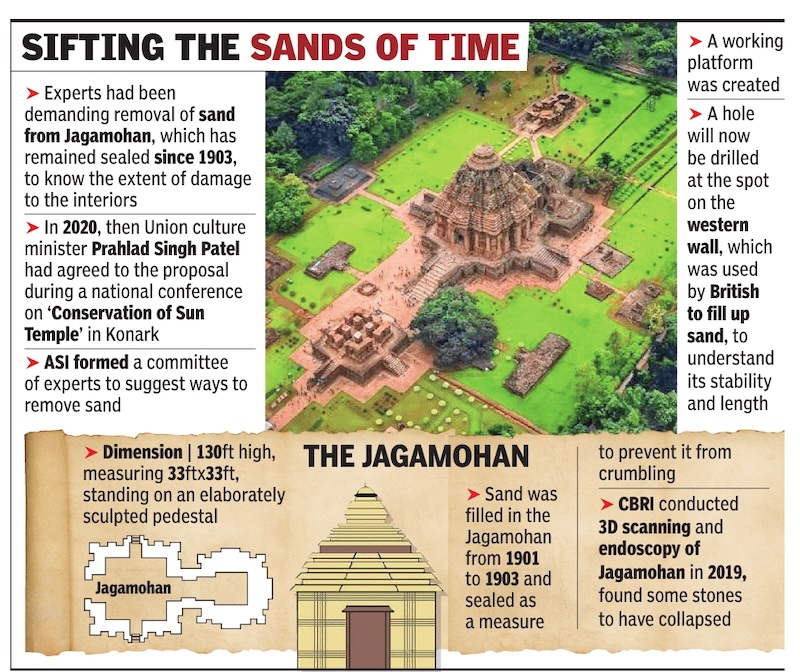

From: Diana.Sahu, December 9, 2025: The Times of India

Bhubaneswar: Drums once thundered beneath its vast stone roof. Priests moved through shafts of light. The Jagamohan — the grand assembly hall of the 13th-century Sun Temple in Konark — was built to hold the living pulse of a kingdom. Today, the same sacred chamber lies entombed in silence, its interior packed with tonnes of sand that kept the hall standing — and hidden — for 122 years.

This weekend, Archaeological Survey of India pierced that silence. Engineers began drilling a narrow hole into the western wall of the Jagamohan — the first physical breach in the sand-filled chamber since the British packed it tight and sealed it shut in 1903. The drilling marks a decisive step in a long-debated plan to remove the sand and reveal what years of hidden damp and pressure may have done to one of India’s most celebrated works of sacred architecture — rising from the edge of the Bay of Bengal in Odisha’s Puri district.

The hole is being drilled between the first and second pidha — the stepped horizontal tiers — on the western wall. It is the exact point where colonial engineers once poured sand into the collapsing hall under orders from Sir John Woodburn, then lieutenant governor of Bengal, fearing the structure would otherwise crumble.

The move comes five years after then Union culture minister Prahlad Singh Patel directed the agency to remove the sand to assess internal damage. Over that period, ASI built a special platform, designed to let experts extract sand without destabilising the monument.

An ASI official said the current phase involves core drilling to test the hidden strength of the wall before any large-scale excavation begins. “The next step will be to create a pocket or a frame through which a tunnel will be dug out to remove the sand. This is a preliminary assessment of the wall because there are no records about its condition and stability,” the official said.

The operation revisits fears that first surfaced nearly 70 years ago. In the mid-1950s, former ASI director general Dr Debala Mitra had carried out exploratory work inside the sealed hall. Her studies revealed that rainwater seeping into the closed interior had triggered the growth of harmful moss due to persistent dampness. That moisture was accelerating the decomposition of the khondalite stone that forms the backbone of the monument, she had said.

Those warnings were confirmed in 2019, when the Roorkee-based Central Building Research Institute examined the structure. Its report found that the sand inside the Jagamohan had settled by nearly 12ft, and that stone blocks from the upper portion of the hall were already dislodging and falling — a sign of invisible stress building within the sealed core.

Designed as a colossal stone chariot for the sun god, Surya, complete with 24 carved wheels and seven horses, the temple once served as a centre of ritual, astronomy and royal power. Over centuries, cyclones, salt-laden winds, shifting sands and rising coastal moisture linked to climate change have eaten into its surfaces, turning conservation into a perpetual race against time. What lies inside this Unesco World Heritage Site remains an open question: intact carvings preserved in darkness, or stone reduced to powder by decades of damp.

[edit] See also

Konark