World War I and India

(→Indian soldiers who defended Britain) |

|||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

Two other Indian pilots who saw action on the Western Front were ''' Lieutenant Srikrishna Welingkar ''' and ''' Lieutenant Eroll Chunder Sen. ''' Welingkar, like Roy, didn't survive, while Sen became a German PoW, released only after the war. Malik joined the Indian Civil Service and had a distinguished career. He became Independent India's first high commissioner to Canada, and Jawahalal Nehru is believed to have made him Indian ambassador to France to use his goodwill among the French to settle the return of French colonies to India. Britain, however, always remembered Malik as the "turbaned young fighter pilot who shot down Germans in the air". | Two other Indian pilots who saw action on the Western Front were ''' Lieutenant Srikrishna Welingkar ''' and ''' Lieutenant Eroll Chunder Sen. ''' Welingkar, like Roy, didn't survive, while Sen became a German PoW, released only after the war. Malik joined the Indian Civil Service and had a distinguished career. He became Independent India's first high commissioner to Canada, and Jawahalal Nehru is believed to have made him Indian ambassador to France to use his goodwill among the French to settle the return of French colonies to India. Britain, however, always remembered Malik as the "turbaned young fighter pilot who shot down Germans in the air". | ||

| − | =Indian soldiers | + | =Indian soldiers in France= |

[http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Faujis-Who-Defended-France-09122014014025''The Times of India''] | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Faujis-Who-Defended-France-09122014014025''The Times of India''] | ||

Revision as of 19:15, 15 December 2014

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

Contents |

India & The Great War

The First World War, or The Great War, as it was then known as, was reported extensively by the then British owned Times of India, with stark details of battles and other events. In particular, the valour of thousands of Indian troops fighting for the British found mention a number of times.

A TOI report dated June 4, 1915 said, “A few weeks ago some papers of the baser sort were hinting at what they were pleased to call the failure of the Indian troops at the front. The object of this was never clear, but it is obvious that the reports must have given enormous pleasure to the Germans who are always glad of an excuse to express their contempt and resentment at the employment of Indian troops against them. The nation which uses poisonous gases and which poisons wells can of course afford to be particular about such matters as the colour of the soldiers whom it fights. But whatever lies and base suggestions may have been circulated, the Germans long ago found out the quality of the men sent to fight them, and in today’s list of the recipients of the Order of British India and the Indian Order of Merit will be found a number of cases recorded in which Indians have shown the greatest gallantry under fire.”

The Suez Canal

The report goes on to describe an incident where Indian troops showed exemplary courage under fire.

“Havildar (now Jemadar) Suba Singh, 56th Punjabi Rifles Frontier Force, in command of a patrol o f nine men on the Suez Canal, surprised and engaged a strong raiding party of Turks estimated at 400 under German officers, and in the fight that ensued he showed a determined front and fought with great gallantry. Although severely wounded, Havildar Suba Singh continued to lead and encourage his men and extricated his patrol from a very difficult situation with a loss of two killed and three wounded, whilst the losses to the enemy were estimated at 12 killed and 15 wounded.”

German praise

Even the Germans had a word of praise for India’s soldiers. A December 5, 1914 report in TOI said: “The Frankfurter Zeitung publishes a letter from a German soldier showing that the Germans are beginning to realize the fighting qualities of the Indians. He says: — “We at first spoke with contempt of the Indians, but today we have learned to regard them in a different light, and they will certainly not be underrated. We lay for three days under shellfire, lacking the barest necessities, and then had a visit from the Indians”.

“The Devil knows what the English have put into those fellows. They stormed our lines as though they possessed an evil spirit, with fearful shouts, compared to which our hurrahs are like the whining of a baby. Thousands rushed at us suddenly as if they had been shot out of the fog.”

“We opened a destructive fire, mowing down hundreds, but others advanced, springing like cats and surmounting obstacles with marvelous agility. They entered our trenches in no time and fought with butt-ends, bayonets, swords and daggers. We had bitter hard work till reinforcements arrived.”

Another article describes Indian troops arriving in France as “a fascinating and mysterious invasion from the Arabian Nights”. The French writer even imagines “Gurkhas creeping at night through the mud towards the enemy’s patrols like tigers”.

Martyrs

A century on, World War I martyrs to be remembered

New Delhi

The Times of India Jul 29 2014

On July 28, 1914 Austria-Hungary fired the first shots to invade Serbia. Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination by a Serbian nationalist a month earlier had proved to be the final straw, even though tensions were escalating for quite some time. This set in motion a chain of events, with Britain declaring war on Germany on August 4, which triggered a conflagration the like of which the world had never witnessed till then. World War-I would last over four years, from 1914 to November 1918, with around nine million troops and many more civilians being killed.

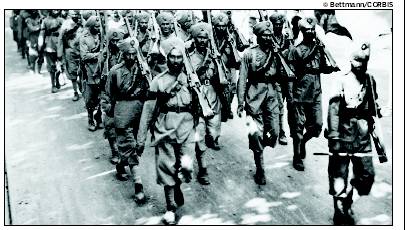

Around 62,000 of them were Indian troops, with another 67,000 being wounded in the trench-to-trench warfare-the norm then. Over a million Indian troops, each paid Rs 11 per month, under the British flag took active part in World War-I, from Sonne and Flanders in France to Gallipoli and Canakkale in Turkey.

“An Independent India may not choose to remember the soldiers who laid down their lives since they were fighting for the British Empire. A soldier is a soldier, whichever the political dispensation that directs him to go to war may be,” said a major-general.All of the 30 regiments or units that took part in the “Great War” and are still part of the Indian Army, from Skinner’s Horse and Madras Regiment to Gorkha and Garhwal Rifles, commemorate their own “Battle Honour Days” in their own unique way.

Indians who lorded over European skies in WWI

Manimugdha S Sharma,TNN | Oct 8, 2014 The Times of India

The First World War had 1.3 million Indians fighting in every theatre of the conflict. A handful of them fought in the air, and one of them became the first Indian fighter ace. Yet outside the Indian Air Force, which celebrated its 82nd anniversary on Wednesday, there seems to be little awareness about the role of India's air warriors in the Great War.

Gurdit Singh Malik

It all started with a Sikh student studying in Oxford expressing his wish to join the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in 1917, when the war had reached a crescendo. Sardar Gurdit Singh Malik was initially denied permission to join the force; he was instead asked to serve as an orderly in an Indian military hospital. "He had to overcome institutional racism to become a fighter pilot for the British before he took on the Germans," said Harbakhsh Grewal of UK Punjab Heritage Association, one of the organizers of the widely acclaimed 'Empire, Faith, War: The Sikhs and World War One' exhibition in Britain.

A disappointed Malik then went to France to help out the beleaguered French as an ambulance driver. There, too, he asked if he could volunteer in the air force. The French agreed. Malik then wrote to his tutor in Oxford about it, who then took it up with the chief of the RFC and said it would be an embarrassment if a British subject had to be employed by the French. "That's when I heard from General Henderson, chief of RFC, who asked me to see him. After that meeting, I was sent for training and got a commission in the RFC as a fighter pilot," Malik had said in a TV interview in the early 1980s. Malik became the first Indian fighter pilot of the RFC, which became the Royal Air Force during the war. With a precedent thus set, the RFC opened its doors to Indians.

Malik shot down six German fighters in those early days of aerial combat when fighter pilots tried to shoot each other down with pistols and rifles when they came too close to each other. The life expectancy of fighter pilots in those days was just 10 days in combat. Yet Malik survived the war despite being wounded in action.

Malik's squadron also duelled with Manfred von Richthofen, the famous 'Red Baron'. But despite his kills, Malik was officially credited with only two and missed out on the title of 'ace' (a pilot who downed five or more enemy aircraft). That credit went to another Indian pilot, Lieutenant Indra Lal "Laddie" Roy.

Lt Indra Lal Roy

Roy was studying in London and had just turned 18 when he volunteered for the RFC. He got a commission and was placed with no. 56 squadron first before being transferred to no. 40 squadron. In just 170 hours of flying, Roy shot down 10 enemy aircraft, thus becoming a full ace. Roy didn't survive the war. He was shot down in July 1918, aged just 19. He was awarded with a Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously.

Two other Indian pilots who saw action on the Western Front were Lieutenant Srikrishna Welingkar and Lieutenant Eroll Chunder Sen. Welingkar, like Roy, didn't survive, while Sen became a German PoW, released only after the war. Malik joined the Indian Civil Service and had a distinguished career. He became Independent India's first high commissioner to Canada, and Jawahalal Nehru is believed to have made him Indian ambassador to France to use his goodwill among the French to settle the return of French colonies to India. Britain, however, always remembered Malik as the "turbaned young fighter pilot who shot down Germans in the air".

Indian soldiers in France

Shashi Tharoor, December 09 2014

Little is known of Indian soldiers who fought World War I, in the war's centenary.

Exactly 100 years after the “guns of August” boomed across the European continent, the world has been extensively commemorating that seminal event. The Great War, as it was called then, was described at the time as “the war to end all wars“. But while the war took the flower of Europe's youth to their premature graves, snuffing out the lives of a generation of talented poets, artists, cricketers and others whose genius bled into the trenches, it also involved soldiers from faraway lands that had little to do with Europe's bitter traditional hatreds. Of the 1.3 million Indian troops who served in the conflict, however, you hear very little.

The most painful experiences were those of soldiers fighting in the trenches of Europe. Letters sent by Indian soldiers in France and Belgium to their family members in their villages back home speak an evocative language of cultural dislocation and tragedy. “The shells are pouring like rain in the monsoon,“ declared one. “The corpses cover the country like sheaves of harvested corn,“ wrote another.

The British raised men and money from India, as well as large supplies of food, cash and ammunition, collected both by British taxation of Indians and from the nominally autonomous princely states. In return, the British had insincerely promised to deliver progressive self-rule to India at the end of the war.

Mahatma Gandhi, who returned to his homeland for good from South Africa in January 1915, supported the war, as he had supported the British in the Boer War. The great Nobel prize-winning poet, Rabindranath Tagore, was somewhat more sardonic about nationalism: “We, the famished, ragged ragamuffins of the East are to win freedom for all humanity!“ he wrote during the war. “We have no word for `Nation' in our language.“

India's absence from the commemo rations, and its failure to honour the dead, were not a major surprise: the general feeling was that India was ashamed of its soldiers' participation in a colonial war and saw nothing to celebrate.

But the centenary is finally forcing a rethink. Remarkable photographs have been unearthed of Indian soldiers in Europe and the Middle East, and these are enjoying a new lease of life online.Looking at them, i find it impossible not to be moved: these young men, visibly so alien to their surroundings, some about to head off for battle, others nursing terrible wounds.

My favourite picture is of a bearded and turbaned Indian soldier on horseback in Mesopotamia in 1918, leaning over in his saddle to give his rations to a starving local peasant girl. This spirit of compassion has been repeatedly expressed by Indian peacekeeping units in UN operations since, from helping Lebanese civilians in the Indian battalion's field hospital to treating the camels of Somali nomads. It embodies the ethos the Indian solider brings to soldiering, whether at home or abroad.

For many Indians, curiosity has overcome the fading colonial-era resentments of British exploitation. We are beginning to see the soldiers of World War I as human beings, who took the spirit of their country to battlefields abroad. The Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research in Delhi is painstakingly working to retrieve memorabilia of that era and reconstruct the forgotten story of the 1.3 million Indian soldiers who had served in World War I. Some of the letters are unbearably poignant, especially those urging relatives back home not to commit the folly of enlisting in this futile cause. Others hint at delights officialdom frowned upon; some Indian soldiers' appreciative comments about the receptivity of Frenchwomen to their attentions, for instance.

Astonishingly , almost no fiction has emerged from or about the perspective of the Indian troops. But Indian literature touched the war experience in one tragic tale. When the great British poet Wilfred Owen (author of the greatest anti-war poem in the English language, `Dulce et Decorum est') was to return to the front to give his life in the futile World War I, he recited Tagore's `Parting Words' to his mother as his last goodbye. When he was so tragically and pointlessly killed, Owen's mother found Tagore's poem copied out in her son's hand in his diary .

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintains war cemeteries in India, mostly commemorating World War II. The most famous epitaph of them all is inscribed at the Kohima war cemetery in northeast India. It reads, “When you go home, tell them of us and say For your tomorrow, we gave our today .“

The Indian soldiers who died in World War I could make no such claim.They gave their “todays“ for someone else's “yesterdays“. They left behind orphans, but history has orphaned them as well. As Imperialism has bitten the dust, it is recalled increasingly for its repression and racism, and its soldiers, when not reviled, are largely regarded as having served an unworthy cause.

But they were men who did their duty, as they saw it. And they were Indians. It is a matter of quiet satisfaction that their overdue rehabilitation has now begun.