Corruption: India

(→The Global Corruption Barometer, 2013) |

(→Transparency International, 2014) |

||

| Line 186: | Line 186: | ||

We could celebrate the fact that India's rank and score have improved in the 2014 rankings over the 2013 ones, but the improvement is too little and from too low a base to warrant such a reaction. India's current score of 38 is way below the 92 that the least corrupt countries like Denmark have achieved and its rank of joint 85th among 175 countries means it is in the middle of the range. If the country is to realize its full economic potential, the situation will have to improve dramatically and soon. The government has a major role to play in ensuring this happens by reducing discretionary powers and making processes more transparent, but civil society too must play its part in the form of anti-corruption movements and constant vigil. | We could celebrate the fact that India's rank and score have improved in the 2014 rankings over the 2013 ones, but the improvement is too little and from too low a base to warrant such a reaction. India's current score of 38 is way below the 92 that the least corrupt countries like Denmark have achieved and its rank of joint 85th among 175 countries means it is in the middle of the range. If the country is to realize its full economic potential, the situation will have to improve dramatically and soon. The government has a major role to play in ensuring this happens by reducing discretionary powers and making processes more transparent, but civil society too must play its part in the form of anti-corruption movements and constant vigil. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =2014: Delhi most corrupt UT= | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Delhi-led-UTs-in-corruption-cases-20082015004029 ''The Times of India''], Aug 20 2015 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Delhi led UTs in corruption cases ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nitisha Kashyap | ||

| + | |||

| + | Delhi Police had to deal with many cases of corruption by government officials in 2014. While the city's ranking was quite low when compared with other states, it topped among other Union Territories in registering corruption complaints. | ||

| + | According to the NCRB data, 64 cases were registered during the year--highest among Union Territories. The city is ranked 15th among other states and Union Territories in registering cases under the Prevention of Corruption Act and IPC against police personnel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While 4,246 cases were registered across the country in 2013, a total of 4,966 cases were registered in 2014. Maximum cases were registered under sections 7 (Public servant tak ing gratification other than legal remuneration in respect of an official act) and 13 (criminal misconduct by a public servant) of Prevention of Corruption Act. Investigation was pending in 163 cases from the previous year. In 2014, only 22 cases were investigated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Only two cases were transferred to local police last year.There were just six cases in which chargesheets were not laid but final reports were submitted. A total of 207 cases are pending for probe, while in 63.6% of cases chargesheet has been registered. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 2014, complaints against police in cases other than corruption decreased. While in 2013, 12,427 complaints were registered, it decreased to 11,902 in 2014. Department inquiry was initiated in only 540 cases, while no case was sent for regular department action. | ||

| + | |||

=Chief Ministers= | =Chief Ministers= | ||

Revision as of 16:09, 21 August 2015

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

The origins and causes of corruption

Time to Rock the Vote

Prem Shankar Jha Tehelka.com, 10 Sep 2011

Paying for running a democracy

Despite 15 parliamentary and over 300 state elections [till 2011], democracy has not empowered the people of India. Instead, it has created a predatory ruling class that has preyed upon them.

Dissatisfaction with democracy is not new. The Nehru years were undoubtedly years of empowerment: the government was honest; it drew up grand plans for ending poverty, and the people believed in them. But the euphoria did not last. Disillusionment first revealed itself in the so-called protest vote — a clear pattern seen in the 1967 General Elections and Congress defeats in state legislatures being associated with a sharp rise in the voter turnout.

Dissatisfaction became endemic in the 1980s. Voters threw out incumbent governments so regularly that this came to be known as the ‘anti-incumbency factor’ — a classic case of calling a symptom a disease. ==Origins: Two flaws in the Constitution CORRUPTION, EXTORTION, criminalisation, the black trishool that has poisoned the heart of the Indian State, can only be eradicated if its roots are fully exposed. The origins of all three can be traced to two deep flaws in the Constitution India adopted in 1950. The first is the omission of a system for meeting the cost of running a democracy, i.e. the entire process of selecting and then electing the peoples’ representatives. The second is the failure to enact provisions that would convert a bureaucracy that had been schooled over a century into believing that its function was to rule the people into its servants.

Meeting the cost of running a democracy

The first arose from an unthinking emulation of the British practice. What the members of the Constituent Assembly forgot was that whereas the average British constituency was 375 sq km in size, and today has an electorate of 60,000, the average parliamentary constituency in India is 6,000 sq km in size and has 1.2 million voters. In Britain, a candidate for Parliament can therefore get into his car every morning, visit two or three towns and villages, and return home every night. But in its Indian counterpart, the typical constituency has more than a thousand villages. To man its 1,000-1,200 polling booths, every serious candidate has to employ at least 8,000 persons on polling day. The cost is, quite simply, enormous. The failure of the Constituent Assembly to understand how this difference in size made it impossible to copy the British model in India was surprising, to say the least.

The oversight could have been remedied with a constitutional amendment at a later date, but instead, in 1967, Indira Gandhi took the country in the opposite direction and choked off the only legitimate source of funds that had sprung up in the intervening years. This was the donations from corporations that all parties, except the Communists, had begun to depend upon.

Gandhi took this decision weeks after the Congress party came close to defeat in the General Election of 1967. Not only did its tally in the Lok Sabha fall from 353 to 282 — only 10 more than what it needed for a majority — but for the first time, it also lost the Assembly elections in six major states. It first repealed the tax concessions on donations to political parties and followed it up three years later with a complete ban on company donations to political parties. But while choking the political system’s main source of funds, she deliberately did not create an alternative.

She did this because her purpose was not, as her party claimed, to reduce the influence of big business on policy-making. The second Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956 had already done this. It was to cripple a rising threat from the right by depriving it of funds. In 1967, the pro-market Swatantra Party, formed by C Rajagopalachari in 1961, and the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) had fought the elections jointly and become a serious threat to the Congress in three states. These were Madhya Pradesh, where the BJS won 78 out of the 296 seats, Gujarat, where the Swatantra Party won 66 out of 168 seats, and Rajasthan, where, by winning 72 seats, they succeeded in reducing the Congress to a minority.

Indira Gandhi’s decision to ban corporate donations to political parties in 1967 took the country in the opposite direction from the one it had taken under Nehru

More than their share of the seats, the Congress feared their much larger share of the vote, for this threatened to turn them into a magnet for the then numerous smaller parties and independents. A two-party, or at least two-coalition, political system, therefore, seemed on the point of being born, but the threat that a second national party could pose to the Congress was too much for its leaders to stomach. It therefore, knowingly, passed a law designed to starve the Opposition of funds that only it, by virtue of being in power, could flout with impunity.

Birth Of The Predator State

The ban on company donations closed the only honest, open and transparent avenue for raising funds to fight elections, which had come into being since Independence. Like Solomon Bandaranaike’s Sinhala-only language policy of 1956, it was entirely opportunistic. And as in Sri Lanka, the harm it has done is beyond measure. For it has deprived all political parties, including the Congress, of the option of remaining honest. It therefore, opened the gates for the entry of crime and black money into politics.

Over almost half a century, we have become familiar with the corruption and extortion that this has bred. But few understand the deadly impact that it has had on Indian politics. Its immediate effect was to all but destroy the centrist Opposition in Indian politics, and strengthen its ideological extremes. The Swatantra, being the most dependent on funds from the corporate sector, simply threw in the towel: most of its members merged with the Jana Sangh. The two socialist parties, the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) and the Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP), weakened rapidly, merged, then joined the Janata Party in 1977 and finally, disappeared altogether. Their place was taken by a host of caste and ethnicity-based political parties that we are familiar with today.

Only the Jana Sangh and the two Communist parties survived relatively unscathed. By the late ’70s, therefore, the dream that India would one day develop a bipolar political system similar to that of Britain had vanished.

A second, more serious effect, has been to stifle intra-party democracy. The ban on company donations made it harder even for the Congress to raise funds, for its managers had to replace a relatively small and stable cadre of large donors with a much larger number of widely dispersed donors, who were prepared to contribute small sums in cash. Over time, the sheer difficulty of doing this every few years has made them extremely reluctant to disturb a financing network once it had been established. In 80 percent of the constituencies, these networks are inevitably local. All the favour-swapping that has to be made to establish them centres on gaining the favour of not only the party in power, but more specifically, the candidate who represents it in the legislature. This is the origin of clientelist politics.

The actual deals are struck by self-appointed lieutenants, who give candidates the elbow room necessary to modify, or get out of, conflicting commitments. Once a network is established, and especially once it has succeeded in getting its candidate elected, the lieutenants have the most powerful of interests in making sure that it is not threatened by a rival. New entrants into politics determined to change things stand little chance of breaking these clientelist networks. Thus, the more Indian democracy has matured, the more it has succeeded in shutting new people out of politics unless they too are prepared to become a part of the existing clientelist networks.

Princelings

A corollary to this has been the rise of the so-called ‘princelings’ — a second generation of leaders in Indian politics who have inherited and not earned their constituencies. In western democracies, when a long-term member of Parliament, National Assembly or Congress dies, the party almost always chooses a successor on the basis of his or her standing in the constituency. In India, by contrast, the death of a senior politician triggers a rush by the operators of his clientelist network (who have all been inducted into the party by then) to Delhi or the state capital to make sure that there is no contest for the vacant seat, and that the dead leader’s wife, son or daughter is nominated to take the parent’s place. They do this because, sentiment apart, this is the one way of making sure that the clientelist network will not be disturbed. While some ‘princelings’ regularly capture headlines, they make up only a small visible fringe of the tribe. A study by Patrick French of the composition of the 2009 Lok Sabha showed 156 MPs (28.5 percent), including 78 from the Congress (37.5 percent), were selected as candidates because of their family connections. What is still more significant is the preponderance of princelings in the younger members. What is more, French found that “nearly half of all MPs aged 50 or under, are hereditary — selected to contest a seat primarily because they are the children of politicians. Thirty-three of the youngest 38 MPs and every Congress MP under the age of 35 entered Parliament because of their birth.

These figures are disturbing not because of their character and ability, which is much higher than the average, but because, as French concluded: “If you do not come from an established ruling family, you have almost no chance of progressing in national politics, unless you join an ideological party such as the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) or the Communist Party of India (Marxist), where lineage is not important.”

Weakening of national leaderships

A third, unforeseen consequence has been the weakening of national leaderships of the main, non-ideological parties. In this too, the Congress was the first sufferer. When donations were legal, the money used to come directly to the president or treasurer of the political party. This ensured that the reins of financial power remained in the hands of its leaders whom the public recognised and could hold accountable for the way it was collected and spent. But once money began to be raised clandestinely, financial power slipped into the hands of anonymous, unaccountable and, more often than not, unsavoury characters. What is more, control over these new money collectors passed more and more out of the hands of the central party leaders into those of the leaders in the states.

Over time, the price that fundraisers demanded kept growing and, with it, the power of the elected leaders to choose candidates or determine policy, declined. One of the first victims of the change was Indira Gandhi herself. Scholars have severely criticised the way in which she concentrated power within the Congress in her own hands during the Emergency, but in reality, this was a defensive action to stem a weakening of her control over the party that only she fully sensed. For by the mid ’70s, she had all but lost control of several charismatic Congress chief ministers, including HN Bahuguna in UP and VP Naik in Maharashtra. Both were able administrators, and Bahuguna in particular, had restored efficient governance in UP after a lapse of several years. The main reason why Gandhi felt obliged to withdraw her trust from them was that they were no longer obeying the Centre’s directives. In all, Gandhi changed the chief ministers in the Congress-ruled states no fewer than 15 times between 1975 and 1977. That she did this during the 21 months of the Emergency, when, in theory, she was at the peak of her powers, shows how much the Centre had been weakened by the changes that had occurred within the party.

The weakening of the central leadership of the Congress has reduced the capacity of the national leaders to take hard decisions in national interest. In 1967, Gandhi was able to overcome the resistance of a powerful regional chief minister in Assam, BP Chaliha, and separate Meghalaya from Assam. Sixteen years later, her inability to control the Punjab Congress precipitated the Khalistan insurgency in the state. Not only was the Punjab Congress responsible for the rise of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, whom it actively fostered in an attempt to break the Akali Party, but three meetings between Gandhi and Sant Longowal in 1983 failed to produce an agreement over four long-standing demands that, if conceded, would have stemmed the rise of separatism in Punjab. This was because she was unable to persuade the state Congress party’s leaders in Punjab (and Haryana), to endorse anything that would give the Akalis an edge over them in the next election. The country paid the price for her failure with 10 years of insurgency and 61,000 civilian lives. Two thirds of the victims were Sikhs.

Criminals in politics: India

The fourth consequence is the entry of criminals into politics. Members of the current Parliament (29 percent) are facing serious criminal charges including murder, arson, rape, kidnapping, dacoity and illegal possession of arms. In the current Bihar legislature, the ratio is 44 percent and in the recently elected West Bengal Assembly, it is 35.1 percent. To think that West Bengal is one of the most law-abiding states in the country!

The final act in the cementing together of the clientelist State and denying access to power to ‘outsiders’ was the establishment of the MPs and MLAs’ Local Area Development Scheme (MPLADS and MLALADS) under which they are allotted plan funds to spend on development projects in their constituencies at their discretion. On paper, this power is hedged with elaborate safeguards to prevent misuse, but in practice there is no effective monitoring of how much of the allocated money is spent on projects and how much finds its way back into the MP or MLA’s pocket. This scheme has completed the conversion of constituencies into zamindaris. But when the allocations for it was raised from Rs 2 crore to Rs 5 crore a year for each MP and from Rs 1 crore to Rs 2 crore for each MLA in the middle of the 2G scam furore, no one, not even Team Anna, voiced a single murmur of protest.

Economic Consequences

The economic consequences of the total denial of honest funding to political parties has been, if anything, even more devastating, for it has transformed what was intended to be a developmental State into a predatory one. This has taken place in four stages.

29 percent of the current MPs are facing serious criminal charges. The ratio is 44 percent in the Bihar legislature. In West Bengal, it is 35.1 percent

In the immediate aftermath of the ban on company donations, the Congress party’s fund managers also found themselves at a loss for where to raise the money to fight elections. In the 1971 Lok Sabha and 1972 Assembly elections, they therefore went back to the same companies and trade organisations from whom they used to accept tax-deductible cheques in the past, and demanded cash. Although most of them complied, they did so unwillingly. Raising money to meet electoral and administrative expenses therefore became more difficult than it had been before. But the gap was filled by owner-managers of small and medium-sized enterprises, traders and shopkeepers, moneylenders, and others in the informal sector with cash to exchange for entitlements and allocations from the government. This was the base of the shift of power from the central to state units of the Congress described earlier.

But small enterprises needed space to grow and rich farmers needed subsidies. The former played a significant role in providing the rationale for Gandhi’s second round of ‘socialist’ controls on ‘big’ business enacted between 1970 and 1973. The latter converted support prices in agriculture that were designed to protect farmers from loss into ‘procurement prices’ that regularly elevated the market price of cereals and ensured a steady and rising stream of profits for rich farmers. The political power of this ‘intermediate class’ not only caused a further fall in the GDP growth rate from 3.7 percent between 1956 and 1967 to 3.1 percent from 1967 to 1975, but prolonged the life of the command economy by another 15 years till 1991.

The defeat of the Congress in the ‘post-Emergency’ 1977 elections triggered something close to a financial collapse in the central Congress party, but left more than half of its state units relatively unaffected. This triggered the second phase of the development of the predatory state, for when the Congress returned to power in 1980, restoring the financial autonomy and pre-eminence of the central command of the party became one of Gandhi’s first preoccupations. It did this by institutionalising a system of commissions and kickbacks on foreign contracts, notably in infrastructure and defence.

Loss to the nation: opportunities foregone

Over four decades, the cost borne by the people, in terms of opportunities foregone, has been astronomical. Two examples, highlighted in the media at the time when they occurred, show how it has been paid. In the late ’70s, the Janata government had obtained World Bank financing for the first of a new generation of fertiliser plants based upon the natural gas from Bombay High to be set up at Thal-Vaishet, south of Mumbai. Based upon international bidding, the consultants employed by the World Bank had recommended that the contract be given to an American firm, CF Braun. But when the Congress returned to power in 1980, it began to negotiate independently with several firms, including Toyo Engineering of Japan and Haldor Topsoe of Denmark, a subsidiary of the state-owned Italian engineering giant, Snamprogetti. When the World Bank refused to reopen the bid, and pulled out of the project, the government went ahead nonetheless, beating the nationalist drum against foreign dictation, hinting at the World Bank’s subservience to the US government, and hence, partiality to CF Braun, proclaiming that it would finance the plant from its own (non-existent) foreign exchange resources.

Eventually, it awarded the contract not only for the Thal-Vaishet plant, but for four others, to Haldor Topsoe. At the time, it was common knowledge that the government had given the contract to Haldor Topsoe in exchange for a handsome kickback. Only later did the public come to know how much the country had to pay for that deal.

CF Braun had been chosen because of all the bidders, it had by far the most energy efficient technology and lowest overall manufacturing cost. Had the original project been implemented with all the safeguards of the World Bank, it would have set the benchmark for the entire future generation of gas-based plants. But it would, unfortunately, have made kickbacks on future projects much harder to obtain.

The award of a single contract for five plants without any international bidding led to an inflation of the capital costs of all the plants. To make matters worse, Haldor Topsoe’s ammonia making technology used 15 percent more energy per tonne of output. These two disadvantages ensured that these plants would never be able to produce urea at internationally competitive prices. The Thal-Vaishet project therefore created a much higher benchmark for capital costs in later plants. These and its higher energy costs had to be offset by subsidies. Since subsidies were designed to ensure a minimum return on capital invested, it ensured that the cost of all future plants would be ‘gold-plated’. Indian taxpayers have been paying the resulting, inflated, subsidies till this day.

Even while the Thal-Vaishet project was being renegotiated, the Ministry of Defence had begun a similar renegotiation of major defence contracts entered into by the Janata government. Two that were eventually reinstated at immensely higher prices (and much higher kickbacks) were the purchase of groundhugging long-range Jaguar fighter bombers for the Indian Air Force, and the Harrier vertical/short take-off aircraft for the Indian Navy from British companies.

Defence purchases

BUT THE country had to wait another five years to gain its first unequivocal understanding of the direction in which the political system had evolved. It got this from an exposé in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter in 1987 of what came to be known as ‘The Bofors Deal’. And in much the same way as is happening now, the details only came to light because of then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi’s determination to clean up the system he had inherited. The investigations that followed the Swedish exposé revealed no fewer than three layers of kickbacks, totalling a mammoth 17 percent of the $1.3 billion contract. So great was public indignation over the deal and its aftermath that the revelation of yet another massive kickback, of 6 percent on the purchase of submarines from the German firm Howalds Deutsche-Werke, went virtually unnoticed.

The loss of money is, however, the least part of the harm that the institutionalisation of kickbacks has done. Kickbacks take time to negotiate. This has meant escalations in cost and a loss of valuable time. The last is unforgivable in defence contracts because it has left the country vulnerable for long periods while kickbacks are being struck. For instance, both Pakistan and India decided to equip their armies with 155 mm Howitzers at more or less the same time in the late ’70s. The Pakistan Army got its guns by the early ’80s. The Bofors deal was only finalised in 1985.

The need to arrange the kickbacks has led to an unhealthy centralisation of even routine procurement in the hands of the civilian staff of the Ministry of Defence. Today, senior armed forces officers openly lament that it takes an average three years for their requisitions to be met.

The institutionalisation of kickbacks has also meant that contracts have often not gone to the most qualified bidders because these have the least need to pay kickbacks in order to secure orders. This was the probable cause of the cancellation of the agreement with CF Braun.

But by far, its biggest effect has been to put the State up for sale. And in doing so, align it with the predators in society. For once it takes a bribe from a bidder, it makes itself a party to whatever the bribe-giver has to do to recover his ‘costs’. The State, thus, ceases to be the people’s watchdog.

The tendering system

This is the source of all the abuses that have crept into the tendering system — the omission of time schedules, the obfuscation of penalty clauses and, once the deal has been struck, the repeated modification of tenders to ensure that only the pre-determined bidder secures the contract. In addition, since the presence of independent consultants makes deal-making more difficult and fraught with risks, government departments have been found to be shy of employing them to plan and execute projects and have insisted on doing so themselves. This has not only removed the last remaining safeguard against graft but contributed to it.

State governments in particular, have taken advantage of this by developing a stratagem for extracting money from projects that only Indian ingenuity could have dreamt up: they chop up large projects into numerous smaller parts in the name of preserving competition, and invite separate tenders for each part. This allows ministers and bureaucrats to award contracts to small companies without the capital base, equipment or track record required to qualify for large projects, but willing to offer almost anything in return for getting a piece of the cake. Highway projects, and more recently a rash of tiny solar power projects, are the most obvious examples of such parsing for profit. The cost in terms of delays, inflation and shoddy work can be judged from the fact that the Golden Quadrilateral highway project, to link Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai — started by former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 1999 with the express purpose of providing a fiscal stimulus to the Indian economy after two years of recession — intended to be completed by 2004, is not even half complete in 2011. What is more, it is incomplete because there were unfinished portions in each and every section of the four highways! By contrast, Chinese companies have built 1,000 km of four-lane highways that measure up to European specifications in Kenya, and another 500 km of high-grade two-lane roads in just three years.

In the three decades or more, since kickbacks became the norm for financing political parties, these practices have spread to every corner of the country and every level of its government. Today, there is hardly a contract from the purchase of a new generation of Main Battle Tank to the construction of a rural road, which is not being preyed upon to extract money. Over the years, bureaucrats at every level, from the secretariats in New Delhi to Block Development Offices in each sub-division, have learnt that they can do with even greater impunity for themselves what their political bosses want them to do for their parties.

Ban on company donations lifted: 2003

Economic liberalisation in 1991 ushered in the third phase of development of the predator-clientelist State. The ban on company donations was finally lifted in 2003, but by then the need for funds far outstripped what industrialists, in the new, fiercely competitive economy, with its vastly reduced scope for favour-swapping, were prepared to pay.

According to a recent study by Indira Rajaraman in 2009-10, corporates, large and small, donated only Rs 130 crore to political parties. But industrialists have found more direct ways of influencing government decisions: they now just buy the concerned decision-makers. This is what the spate of scams in the 1990s and 2000s has shown.

The fourth and final stage of development of the mature clientelist State occurred when coalition rule at the Centre became the rule. Look at all the five governments formed since 1996 and you will find that while the ‘national’ party, be it the Congress or the BJP, has retained the ‘power’ portfolios — defence, home, external affairs and the prime ministerships, all but a few of the ‘money’ portfolios have been taken by its regional coalition partners. That is the root of the 2G scam. But the 2G scam is only an extreme case of what is now everyday, routine ‘business’.

[We are] indulging in wishful thinking if it believed that even the Lokpal of [our] dreams will make more than a dent in this awesome edifice of corrupt power. Nothing will change till political parties are once more freed from the need to break the law to stay in business and given the option to be honest once again. The only way to do this is to start a very large State fund for financing the electoral expenses of recognised political parties. This requires a much-strengthened Election Commission with a powerful auditing wing, and the adoption of strict and transparent criteria for awarding recognition to political parties. Other reforms can be built upon this foundation. But without it, all the rest will fail.

Mr Prem Shankar Jha, as a top-rung journalist, has had a ringside view of Indian governance.

premjha@airtelmail.in

Corruption: a ‘fact of life’ in India-US embassy

From the archives of The Times of India

New Delhi: The US embassy in July 1976 said corruption in India was a “cultural/political/economic fact of life”, and that it was not a Western import but historically a local phenomenon. It called the Congress party India's "united givers fund”. “It is impossible in any single message to give a description of the extent and modalities of corruption in India. Entire books have been written on this subject and there is little doubt but that these only dealt with the tip of the iceberg. It should be added that corruption is not a phenomenon which was brought to India by the West. Kautilya, the ancient philosopher, in his treaties Arthasastra refers to various kinds of corruption and prescribes corresponding punishments.” The cable said corruption was not confined to the business or political world. “Hindu and other religious shrines in India have long been known for their corrupt practices,” the cable said.

The Global Corruption Barometer, 2013

Graft in India twice the global average

Kounteya Sinha TNN 2013/07/10

London: Corruption in India has reached an all-time high with rates being exactly double of the global prevalence. Globally, 27% people say they paid bribes when accessing public services and institutions in the last year.

In India, however, the number of people who did the same was 54%. Political parties have been found to be the most corrupt institution in India with a corruption rate as high as 4.4 on a scale of 5 (1 being the least corrupt and 5 highest).

The highest amount of bribe however was collected by the police — 62% followed by to those involved in registry and permit (61%), educational institutions (48%), land services (38%). India’s judiciary has also been found guilty — 36% involved in bribes. Cynicism about a corruption free future is widespread among Indians with 45% saying they don’t think common man can make a difference.

On the other hand, around 34% people (1 in 3) said they wouldn’t report corruption if they face it. These are the findings of the Global Corruption Barometer 2013 — a survey of 1.14 lakh people in 107 countries released on Tuesday.

The index found that corruption is widespread globally, with 27% of respondents (1 in 4 people) having paid a bribe when accessing public services and institutions in the last 12 months, revealing no improvement from previous surveys. More than one person in two thinks corruption has worsened in the last two years. The police and the judiciary were seen as the two most bribery prone globally.

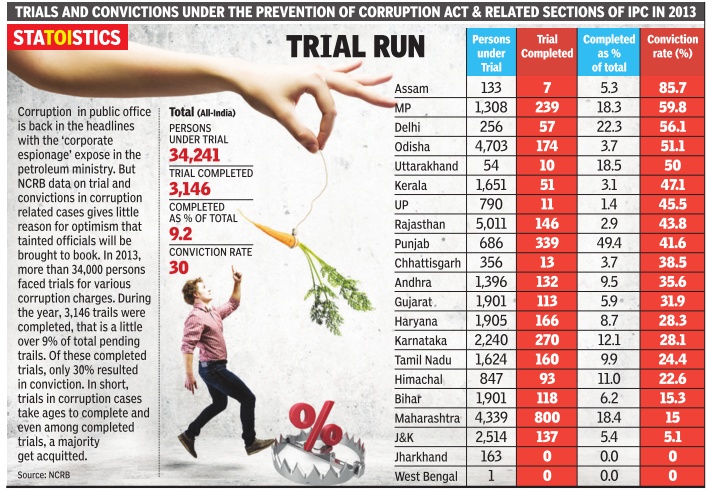

Number of complaints: 2013-14

The Times of India, Aug 04 2015

`82% rise in graft plaints in a yr'

Grievances up 64k in 2014 as compared to 35k in 2013: CVC

The Central Vigilance Commission received an unprecedented 64,000 corruption complaints last year--a jump of 82% from the preceding year. In its annual report for 2014 laid before Parliament, the CVC said the maximum number of complaints about alleged corruption was received against railways employees. Despite the manifold increase in the volume of work being handled by the commission, there has been no increase in the staff strength.“It is for the first time that the commission had received such a high number of corruption complaints,“ a senior CVC official said. Of the total complaints received, 36,115 were vague or unverifiable, 758 were anonymous or pseudonymous and 24,012 were for officials not under CVC. There were 1,214 verifiable complaints which were sent for inquiry or investigation to chief vigilance officers (CVOs) who act as a distant arm of the CVC and CBI.

About 45,713 complaints of corruption were received by the CVOs against government employees. Of these, 32,054 were disposed and 13,659 were pending. A total of 6,499 complaints were pending for more than six months, it said.

A total of 3,378 corruption complaints were received against officials working in the ministry of petroleum and natural gas, 2,917 against employees working under urban development, 1,494 against those in steel ministry and 1,303 against department of telecommunications employees, the annual report said. There was a vacancy of 58 employees, as against the sanctioned strength of 296 in CVC, the annual report said. The CVC tendered advices in 5,867 cases during 2014.

Transparency International, 2014

India less corrupt than China: Study TIMES NEWS NETWORK The Times of India Dec 04 2014

But Still Ranks With Burkina Faso, Benin

For the first time in 18 years, India ranks as less corrupt than China in the annual corruption survey by global watchdog Transparency International.

In its annual survey of 175 countries, India ranks an otherwise depressing 85th, but has improved in the index, jumping 10 places.

China, on the other hand, has fallen 20 places to rank 100th despite Chinese president Xi Jinping unleashing a massive campaign against corruption, arresting a number of high profile political and military leaders. While India and China were at more or less similar levels in 2006-07, this is the first time since the rankings started in 1996 that India is perceived to be less corrupt than China. The Corruption Perception Index is compiled by experts like banking institutions, big companies and other organizations based on their view of corruption in the public sector. Transparency International's annual report measures perceptions of corruption using a scale where 100 is cleanest and 0 most corrupt. India's score moved up to 38 from 36. Despite a slightly better showing by India, its contemporaries on the index are countries like Burkina Faso and Benin, nothing to write home about.

The Berlin-based organi zation published its 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index of 175 countries on Wednesday .Turkey and China showed the greatest drops in the index.

India's perception improvement is attributed to a heightened awareness and public antipathy to corruption from the time Anna Hazare began his agitation in 2012. This was succeeded by the first ever Lokpal Bill being passed in parliament. India's reputation has also been burnished somewhat by the pending anti-corruption bills wending their way through Parliament. Corruption was a major plank in the election campaign in the recently concluded general elections, a central part of BJP's pitch. Even Arvind Kejriwal's short-lived government in Delhi was premised on an anti-graft platform.

The top performer is Denmark at 92. In a statement, Transparency International said it is campaigning for countries to adopt a procedure called Unmask the Corrupt, urging the EU, US and G20 countries to follow Denmark's lead and create public registers that would make clear who really controls, or is the beneficial owner, of every company .

Times View

We could celebrate the fact that India's rank and score have improved in the 2014 rankings over the 2013 ones, but the improvement is too little and from too low a base to warrant such a reaction. India's current score of 38 is way below the 92 that the least corrupt countries like Denmark have achieved and its rank of joint 85th among 175 countries means it is in the middle of the range. If the country is to realize its full economic potential, the situation will have to improve dramatically and soon. The government has a major role to play in ensuring this happens by reducing discretionary powers and making processes more transparent, but civil society too must play its part in the form of anti-corruption movements and constant vigil.

2014: Delhi most corrupt UT

The Times of India, Aug 20 2015

Delhi led UTs in corruption cases

Nitisha Kashyap

Delhi Police had to deal with many cases of corruption by government officials in 2014. While the city's ranking was quite low when compared with other states, it topped among other Union Territories in registering corruption complaints. According to the NCRB data, 64 cases were registered during the year--highest among Union Territories. The city is ranked 15th among other states and Union Territories in registering cases under the Prevention of Corruption Act and IPC against police personnel.

While 4,246 cases were registered across the country in 2013, a total of 4,966 cases were registered in 2014. Maximum cases were registered under sections 7 (Public servant tak ing gratification other than legal remuneration in respect of an official act) and 13 (criminal misconduct by a public servant) of Prevention of Corruption Act. Investigation was pending in 163 cases from the previous year. In 2014, only 22 cases were investigated.

Only two cases were transferred to local police last year.There were just six cases in which chargesheets were not laid but final reports were submitted. A total of 207 cases are pending for probe, while in 63.6% of cases chargesheet has been registered.

In 2014, complaints against police in cases other than corruption decreased. While in 2013, 12,427 complaints were registered, it decreased to 11,902 in 2014. Department inquiry was initiated in only 540 cases, while no case was sent for regular department action.

Chief Ministers

Jaya first CM in office to be convicted

The Times of India TIMES NEWS NETWORK Sep 28 2014

Several Indian politicians, including former and serving CMs, have been imprisoned for political reasons and a handful have been jailed on corruption charges. But J Jayalalithaa is the first CM in office to go to jail on the charges of amassing illegal wealth.

Former CMs jailed for corruption are Lalu Prasad, Madhu Koda, B S Yeddyurappa, O P Chautala and Jagannath Mishra.

Lalu Prasad was the first former CM to be imprisoned in a corruption case. He was first jailed in July 1997 in one of the fodder scam cases. He was finally convicted in September last year. Three-time CM of Bihar Jagannath Mishra was first jailed in 1997.He too was convicted in September 2013.

Jharkhand ex-CM Madhu Koda, was sent to jail in November 2009, facing charges of having accepted bribes for allotting mining contracts in the state. Karnataka ex-CM B S Yeddyurappa was charged with favouring his sons in land allotments.

Om Prakash Chautala, the former CM of Haryana, was charged with taking bribes for recruiting 3,000 teachers and sentenced to 10 years in jail.

CISF’s cash limit upheld

HC okays CISF rule that staff on duty can have only Rs 20

Rosy Sequeira

Mumbai:

The Times of India Nov 05 2014

The Bombay high court has upheld a 2007 circular of the Central Industrial Security Force allowing its personnel to keep only up to Rs 20 with them while on duty .

A division bench of Justices N H Patil and R V Ghuge agreed that the measure was a step towards curbing illegal gratification and possible security breach at various sensitive locations. The court said the office ordercircular of August 23, 2007, cannot be a substitute to a rule or service condition but “keeping in view the object and purpose for which the CISF has been brought into existence, we are of the opinion that the office order needs to be given due importance“.

The ruling came on a plea by constable Ram Tiwari, who was found on August 3, 2008, with Rs 500 while on duty at JNPT, Navi Mumbai. On April 10, 2009, constable Ram Tiwari was held guilty of illegal gratification and removed from service. On September 8, 2009, “keeping in mind his unblemished service record of 16 years“, CISF authorities replaced the punishment with “compulsory retirement“ with full pension. The chargesheet said an inspector saw Tiwari counting money and directed a sub-inspector to frisk him. While removing Tiwari's belt, notes worth Rs 500 fell near his leg. Tiwari denied the money belonged to him and claimed the inspector implicated him due to an animosity .

CISF advocate Vinod Joshi argued that the Rs 500 found on Tiwari could only have come by way of bribes as he had declared before duty he had only Rs 20. The possibility of CISF personnel indulging in illegal gratification from container drivers cannot be ruled out and to curb such acts the circular allowed “CISF personnel on duty to keep only Rs 20 on their person as pocket money“. Joshi said if the punishment is set aside, it will send a wrong signal and “seriously affect the discipline maintained in the CISF“.

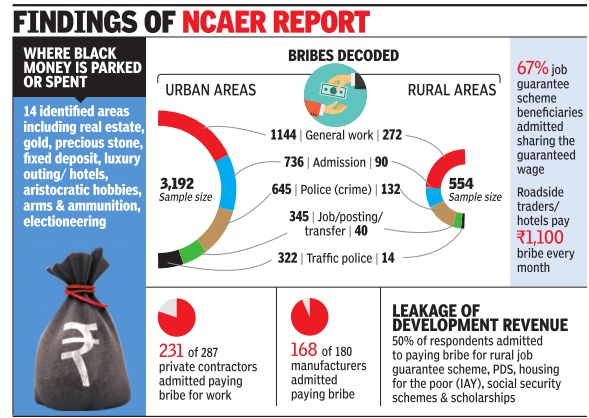

2015: Survey by National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER)

The Times of India May 24 2015

Dipak Dash

Govt survey pegs bribe at Rs 4,400yr per family

An average urban household in India pays around Rs 4,400 annually as bribe while rural households shell out Rs 2,900, a government-commissioned study on unaccounted wealth has revealed. Individuals in Lucknow, Patna, Bhubaneswar, Chennai, Hyderabad, Pune and rural areas paid maximum amount of bribe for general work, admission and to police personnel, the survey by National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) showed.

In the cities, an average Rs 18,000 was paid for securing jobs and transfers, while bribes to traffic police personnel totalled Rs 600 a year. The survey was conducted between September and December 2012. Surveys showed that black money is generated through bribes and pay-offs to bureaucrats and politicians, which could range from award of contracts to leakages from development schemes, mining, sale of oil products and settlement of non-performing loans by banks.

The National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), along with the National Institute of Public Finance & Policy and National Institute of Financial Management, had been tasked by the Centre to provide black money estimates, following an observation by the parliamentary standing committee on finance. While the reports were submitted to the finance ministry in 2013 and 2014, it is only now that they have been circulated for comments from other departments.

Pointing out that bribe is rampant in rural areas, the NCAER survey report has revealed how half the beneficiaries of government schemes, including MNREGS, public distribution system, Indira Aawas Yojna, social security programmes and scholarships had to offer money to get their entitlement. This finding is based on a survey of 359 households in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra. Despite government claims, the report estimates that leakages are more common under MNREGS.

It also highlights the extent of corruption, which ultimately generates black money , so far as public sector investment is concerned. Based on interviews of retired government officials, the report suggested that public sector investment is an easy source of illegal funds for politicians and bureaucrats. The unaccounted money earned could be 2-10% of the project cost and it could cross 20% due to delays. The report estimated that 5-10% of the additional cost in siphoned off.

Based on a survey of private contractors in 15 states, including Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, the report says on an average 9% of the project cost is paid as bribe. About 80% of contractors interviewed have admitted of paying bribe for works. It is no different so far as manufacturing sector is concerned. According to the report, 91% of the respondents admitted to have paid bribe.

The report has also brought to light how on an average people running roadside vends and eateries pay approximately Rs 1,100 per month. These findings are based on a survey in Delhi, Noida, Lucknow, Patna and Hyderabad. The report says about 13% of the earnings are given as bribe.