Moreh

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Ties with Myanmar

As in 2021

Amava Bhattacharya, February 7, 2021: The Times of India

From: Amava Bhattacharya, February 7, 2021: The Times of India

From: Amava Bhattacharya, February 7, 2021: The Times of India

Why this Manipur town is keeping one eye on Myanmar

Decades-old trade ties between Moreh and the markets of Myanmar come under threat as the double whammy of Covid and coup seals borders

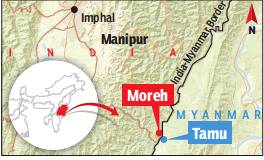

For years, the border town of Moreh, 107km from Imphal, has been the gateway to Myanmar. Literally, because all Indians have to do is hop across the India-Myanmar Friendship Gate without a passport and visa to get access to the bazaars of Tamu and Namphalong, both buying and selling goods and tying the two countries with the umbilical cord of commerce.

But the past 11 months have shut off this key gateway to their livelihood. In March, following the outbreak of Covid, the border was sealed. And on February 1, the day the Union Budget was announced, the Myanmar military staged a coup, which put paid to any chance of it reopening soon.

But Moreh’s multi-cultural mix of Kukis, Meiteis, Tamils, Biharis, Marwaris and Nepalis are nothing if not pragmatic. Far away from the diplomatic enclaves of New Delhi and Yangon, the people of Moreh and its Myanmarese counterpart Tamu feel that such is their dependence on each other that no coup can impact their business for long. “We have been doing business with Myanmar for decades, including when the junta was in power from 1962 to 2011. This latest coup should not affect our ties. Our only concern is the prolonged closure of the border. The Myanmarese side first said it would reopen on December 31, then January 31. Now with the situation changing in Yangon, it looks like the border will be shut for a while,” says Thilla Khan, Moreh resident and office-bearer of the local Tamil Sangam (association).

Khan belongs to the 3,000-strong Tamil community, which has, for long, controlled border trade. The Tamils who have settled in Moreh are descendants of refugees — mostly businessmen, traders, small shopkeepers — who fled Burma between 1948 and the 1960s, though most came after the first coup in 1962. Unable to adjust to life in Tamil Nadu where they first landed, a group of Tamil Chettiars made their way to Moreh in a bid to retur n to Bur ma. Stopped by the Burmese army, they chose to put down roots in this border town.

In the process, they’ve left their stamp on it, with a Tamil style shrine and a smattering of idli dosa stalls. Besides Tamil, most members of the community speak a cocktail of languages like Kuki, Burmese, Meitei, Hindi, and English and rely on cross-border trade for a living. Such was the draw of the ‘Burma trade’ that Khan, who was born in Ramanathapuram district of Tamil Nadu where his family had landed after their expulsion from Burma, migrated to Moreh against his family’s wishes.

The goods traded across the border are numerous, ranging from banians, lungis and sarees to food items like powdered milk and medicines. These are sold both in Myanmar’s Namphalong market, at walking distance from Moreh market, and in Tamu, further inside. Since Chinese and Thai goods are very easy to find in Namphalong, traders often bring back household items like rice cookers and mosquito bats for sale in Moreh and from there to other parts of India.

While traders are confident it will be business as usual even after the coup, general secretary of the Moreh Border Trade Chamber of Commerce, the Myanmar-born Surinder Singh Patheja, admits to being a bit apprehensive. “During civilian rule in Myanmar, the scope of India-Myanmar trade relations had expanded. Sixty-two items can now be traded duty-free, while for the rest, customs duty is required. We are already hearing of pro-democracy protests even in Tamu,” says Patheja, who arrived in Delhi from Burma in 1962 and then settled in Moreh ten years later. The Punjabi community in the town has declined from 40 families earlier to 13, but many still have relatives in Myanmar. Some have managed to go across and visit after 2018 when travel to Myanmar proper was allowed from Moreh with visa and passport.

It is the Myanmar military’s perceived proximity to China that has most worried traders like Khan. “It is difficult to compete with Chinese goods like electronics, mobiles, clothes, electrical parts and so on. They have flooded Namphalong market and affected our business. We have heard that the military in Myanmar is close to China. While they don’t interfere with local trade, it is better for India if there are democratic governments across the border,” he says.

E Bijoykumar Singh, professor of economics at Manipur University, confirms that the inflow of Chinese goods to Myanmar has increased over the years. “Some Chinese traders are said to be learning Manipuri to access the markets,” he says. However, even with the borders shut, Moreh’s ‘informal economy’ kept it going. Like every border town, there is an illegal flow of narcotics and gold. “Gold and drugs kept moving as usual, and will continue to do so, regardless of who is in power. However, it is important that the border reopens soon,” says Singh.

With the Modi government changing the ‘Look East’ policy to a reinvigorated ‘Act East’ policy, the strategically located town was hoping that it would be catapulted to an important trading post. The key to this transformation was the planned Trans Asian Highway, points out Ch Ibohal Meitei, director of Manipur Institute of Management Studies. “The Asian Highway (AH-1), part of the India-Myanmar-Thailand trilateral highway, is expected to connect Moreh to Mae Sot in Thailand, via Mandalay and Yangon in Myanmar. India has abolished ‘border trade’ in Moreh, and made way for ‘normal trade’. Now, large-scale infrastructure — warehouses, good roads and fewer security checkposts — are needed for Moreh to make the leap from informal border trade to a more transparent system of exchange of goods,” he says.

But till that happens, the Asian Highway remains a signboard on a rough road. And Moreh — existing between trades formal and informal, India and Myanmar, democracy and military — waits for its border to reopen.