Kolhapur State

Contents |

Kolhapur State, 1908

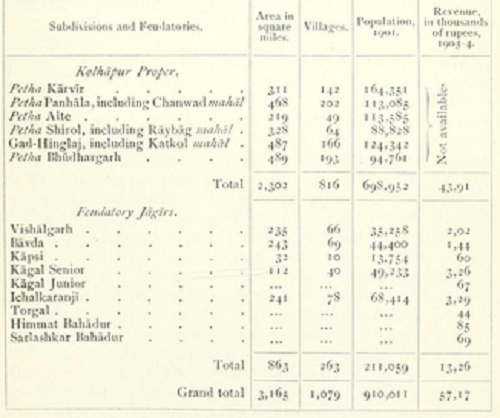

(or Karavira, or Karvir). — State in the Kolhapur and Southern Maratha. Political Agency, Bombay, lying between 15 degree 50' and 17 degree 11’ N. and 73 degree 43' and 74 degree 44' E. 1 , with an area of 3,165 square miles. It is bounded on the north by the river Varna, which separates it from the District of Sa.ta.ra ; on the north-east by the river Kistna, separating it from Sangli, Miraj, and Kurandvad ; on the east and south by the District of Belgaum ; and on the west by the Western Ghats, which divide it from Savantvadi on the south- west and Ratnagiri on the west. Kolhapur comprises portions of the two old Hindu divisions of Maharashtra and Carnatic, a distinction which is still marked in the language of the people, part of whom speak MarathI and the remainder Kanarese. Subordinate to Kolhapur are nine feudatories, of which the following five are important : Vishalgarh, Bavda, Kagal (senior), Kapsi, and Ichal- karanjl. The general statistics of all of these are shown in the table on the next page.

Physical aspects

Stretching from the heart of the Western Ghats eastwards into the plain of the Deccan, Kolhapur includes tracts of widely different cha- racter and appearance. In the west, along the spurs Of the main chain are situated wild and picturesque hill slopes and valleys, producing timber, myrabo- lams, &c, and covered with forests. The central belt, which is open

1 These spherical values do not include certain outlying tracts, like Torgal. and fertile in parts, is crossed by several lines of low hills running east and west at right angles to the main range. Farther east, the land becomes more open, and presents the unpicturesque uniformity of a well-cultivated and treeless plain, broken only by an occasional river. Among the western hills are perched the forts of Panhala, Vishalgarh, Bavda, Bhudhargarh, and Rangna, ancient strongholds of the Kolhapur chieftains. The State is watered by eight streams of considerable size ; but though navigable during the rainy months by trading boats of 2 tons, none is so large that it cannot be forded in the hot season. The only lake of any importance is that of Rankala, near the city of Kolhapur. It has lately been improved at a considerable cost. Its circumference is about 3 miles, and its mean depth 3$ feet. Except in the south, where there are some ridges of sandstone and quartzite belonging to the Kaladgi (Cuddapah) formation, Kolhapur comes within the area of the great Deccan trap fields.

The chief trees are the ain, nana, hirda, kinjal, jdmbul, and bava ; minor products are bamboos, myrabolams, and grass. Tigers and leopards are found in the hills. Bison, bears, and wild dogs are occasionally met with.

At an elevation of about 1,800 feet above the sea, Kolhapur enjoys on the whole a temperate climate. In the west, with its heavy rainfall and timber-covered hills and valleys, the air keeps cool throughout the year ; but in the dry tracts below the hills, suffocating easterly winds prevail from April to June. During the hot months the hill forts, rising about 1,000 feet above the plain, afford a pleasant retreat. The annual rainfall is heaviest at Bavda, where it reaches 207 inches, and least at Shirol, where it is only 21 inches. Kolhapur and Ajra record an average fall of 38 and 77 inches. Plague first appeared in the State in 1897, and caused more than 62,000 deaths by the end of 1903-4.

History

The members of a branch of the Silahara family, which was settled above the Western Ghats, possessed the territory lying round Kolhapur and in the north-west of Belgaum District from about the end of the tenth century to early in the thirteenth century. About 1212 the country passed to the Deogiri Yadavas. The ancient Hindu dynasty was subverted by the Bahmani kings of the Deccan, and the country afterwards came under the rule of Bijapur. In 1659 Sivaji obtained possession of the forts which, though taken and retaken many times, finally remained with the Marathas on the death of Aurangzeb.

The present Rajas of Kolhapur trace their descent from Raja Ram, a younger son of Sivaji, the founder of the Maratha power. After the death of Raja Ram in 1700, his widow placed her son Sivaji in power at Kolhapur. But in 1707, when Sha.hu, the son of Sambhajl, Sivaji's elder son, was released from captivity, he claimed the sovereignty over all the possessions of his grandfather and fixed his capital at Satara. Disputes between the two branches of the family continued for several years, till in 1730 a treaty was concluded, under the terms of which the younger branch agreed to yield precedence to Sha.hu, and to abandon all claims to the country north of the Varna and east of the Kistna, and Shahu of the elder branch recognized Kolhapur as an independent prin- cipality. On the death of Raja Ram's younger son in 1 760, the direct line of Sivaji became extinct ; and a member of the family of the Bhonslas was adopted under the name of Sivaji III. The prevalence of piracy from the Kolhapur port of Mai van compelled the Bombay Government to send expeditions against Kolhapur in 1765, and again in 1792, when the Raja, agreed to give compensation for the losses which British merchants had sustained since 1785, and to permit the establishment of factories at Malvan and Kolhapur. Internal dissen- sions and wars with the neighbouring States of the Patvardhans, Savantvadi, and Nipani, gradually weakened the power of Kolhapur. In 181 2 a treaty was concluded with the British Government, by which, in return for the cession of certain forts, the Kolhapur chief was guaranteed against the attacks of foreign powers ; while on his part he engaged to abstain from hostilities with other States, and to refer all disputes to the arbitration of the British Government.

During the war with the Peshwa in 1817, the Raja of Kolhapur sided with the British. In reward, the tracts of ( 'hikodi and Manoli, formerly wrested from him by the chief of Nipani, were restored. But these tracts did not long remain a part of the State. They were resumed by the British Government in 1829, owing to the serious misconduct of the Raja. Shahajl, alias Bava Sahib, who came to the throne in 1822, had proved a quarrelsome and profligate ruler ; and, in consequence of his aggressions between 1822 and 1829, the British were three times obliged to move a force against him. On his death in 1837 a council of regency was formed to govern during the minority of Sivaji IV. Quarrels arose among the members of this council, and the consequent anarchy led to the appointment by the British Government of a minister of its own. The efforts, however, which he made to reform the adminis- tration gave rise to a general rebellion, which extended to the neigh- bouring State of Sa.vantva.di. After the suppression of this rising, all the forts were dismantled, and the system of hereditary garrisons was abolished. The military force of the State was disbanded and replaced by a local corps. In 1862 a treaty was concluded with Sivaji IV, who was bound in all matters of importance to be guided by the advice of the British Government. In 1866, on his death-bed, Sivaji was allowed to adopt a successor in his sister's son, Raja Ram. In 1870 Raja Ram proceeded on a tour in Europe, and, while on his return journey to India, died at Florence on November 30, 1870. Sivaji Maharaja Chhatra- pati V succeeded Raja Ram by adoption. In 1882 he became insane, and Government was compelled to appoint a council of regency, headed by the chief of Kagal as regent. Sivaji V died on December 25, 1883, and having no issue, was succeeded by adoption by Jaswant Rao, alias Baba Sahib, under the name of Shahajl, who still rules. The Maharaja of Kolhapur holds a patent authorizing adoption, and succession follows the rule of primogeniture. He is entitled to a salute of 19 guns.

Population

The population of Kolhapur and its feudatories was 804,103 in 1872, 800,189 in 1881, 903,131 in 1891, and 910,011 in 1901, residing in 9 towns and 1,070 villages. The towns are Kolha- pur (population, 54,373), the capital, IchalkaranjI (12,920), Shirol (7,864), Kagal (7,688), Gad-Hinglaj (6,373), Wad- gaon (5,168), Hatkalangda (3,680), Katkol (4,562), and Malkapur (3,307). The density is 319 persons per square mile. About 90 per cent, are Hindus ; and of the remainder, 38,533 are Musalmans, 50,924 Jains, and 2,517 Christians. The chief Hindu castes are Brahmans (33,000), of whom two-thirds are Deshasths (22,000), while Konkanasths number 5,000. Marathas (432,000) form the majority of the Hindu population, and are largely cultivators, describing themselves as KunbTs. The Dhangar or shepherd caste numbers 36,000, mostly nomads. Lingayats, who are chiefly found in the south, number 79,000, largely traders and shopkeepers. Mahars (74,000), Mangs (17,000), and Sutars or carpenters (15,000) are the remaining castes of numerical importance. Kolhapur is remarkable for the large number of Jain cultivators (36,000), who are evidence of the former predo- minance of the Jain religion in the Southern Maratha country. They are a peaceable and industrious peasantry. The Musalmans chiefly describe themselves as Shaikhs (31,000). Native Christians numbered 2,462 in 1901 ; and of these 1,087 w ere Roman Catholics, 1,048 Pro- testants, and 100 Presbyterians. Nearly 71 per cent, of the total population are supported by agriculture, while 13 per cent, belong to the industrial classes.

Agriculture,&c.

The soil is of four kinds : namely, kali or black, tCunbdi or red, malt or malav, the alluvial land, and khciri or pandhari or white. Of these, the black and red soils are the most valuable. About one-third of the arable area is good soil yielding garden crops ; but the remainder is mediocre, or, in the hilly parts, poor. Of the 2,354 square miles of cultivable land, 2.019 square miles have been brought under cultivation. In 1903-4 the area actually cultivated was 1,591 square miles, the remaining 428 square miles being current fallows. Jowcir occupied 470 square miles, rice 262, ndclini 171, and bajra 108 square miles. Other crops are sugar-cane, tobacco, cotton, chillies, kusumba, and ground-nuts. A few coffee and cardamom plantations yield a small out-turn. Irrigation is rare, and is carried on chiefly from wells or pools dug in stream beds. The area of 'reserved' forest is 341 square miles, while 182 square miles are pro- tected ; the forest products are teak, sandal, black-wood, myrabolams, grass, and honey. The hollows of rocks and decayed trees contain the comb of thepova bee, which is highly esteemed.

Iron ore of three varieties is found in Kolhapur territory. It is most plentiful in Yishalgarh, Panhala, Bhudargarh, and Kolhapur proper, near the main range of the Western Ghats. In these places it is gene- rally found near the surface, in laterite. Formerly the smelting of iron was an industry of some importance; but, owing to the cost of manual labour, the increased price of fuel, and the low rates of freight from England, the Kolhapur metal cannot compete with that imported from Europe. Stone is the only other mineral product of the State. There are several good quarries, especially one in a place known as Jotiba's Hill, with a fine-grained basalt, that takes a polish like marble.

Trade and communications

Rosha oil is manufactured in the State. Other manufactures are pottery, hardware, coarse cotton, woollen cloth, felt, liquor, perfumes, and lae and glaSS ornaments - Coarse sugar, tobacco, cotton , and grain are the chief exports ; and refined sugar, spices, coco-nuts, piece-goods, silk, salt, and sulphur are the principal imports. The most noteworthy centres of local trade with permanent markets are Kolhapur city, Shahupur, Wadgaon, Ichalkaranji, and Kagal. 'The Southern Mahratta Railway passes through the State, being connected with Kolhapur city by a branch opened in 1891, the property of the State. Six principal lines of road pass through Kolhapur territory, the most important being that from Poona to Belgaum, which crosses the State from north to south. The total number of post offices is 42, of which 9 are situated in the

feudatory jagirs.

Famine

Kolhapur, with its good rainfall and rich land, is less liable to famine than the adjacent Deccan Districts. Distress occurred in the years 1876-7, 1 89 1-2, 1896-7, and 1 899-1 900, and relief measures were necessary on each occasion. the highest daily attendance of persons in receipt of relief was 164,344 in 1876-7, 6,200 in 1891-2, 61,616 in 1896-7, and 7,000 in 1899-1900. About 3 lakhs were spent on relief in 1876-7, Rs. 40,000 in 1 891-2, 7 lakhs in 1896-7, and Rs. 51,000 in 1899-1900.

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Administration

The nine feudatory estates are administered by their holders. Kolha- pur proper is divided into six pethas or talukas and three mahais, and is managed by the Maharaja with the advice of the Political Agent, Kolhapur and Southern Maratha Jagirs.

The Maharaja exercises full powers in criminal and civil matters, including the power of life and death ; but he cannot try British subjects for capital offences without the permission of the Political Agent. The State contains 64 criminal courts with varying powers from Sessions Judge to third-class magistrate. The feudatory chiefs have in most cases power to imprison up to seven years and the civil powers of a District Judge. During their minority, their karbharis exercise jurisdiction as magistrates and sub-judges. The commonest forms of crime are theft and hurt. There are municipalities at Kolhapur, Narsoba Vadi, Ichalkaranji, Wadgaon, Hatkalangda, Shirol, Gad-Hinglaj, Katkol, and Malkapur. The income of the Kolhapur municipality exceeds Rs. 60,000, while that of the remaining eight amounts in all to about Rs. 23,000. The Kolhapur municipality was suspended in 1904, owing to maladminis- tration.

The land revenue administration is controlled by an officer styled the Chief Revenue Officer, corresponding to the Commissioner of a British Division. The Kolhapur land tenures belong to three main classes : namely, alienated or inami, State or sheri, and personal or ryotwari. Of these, the alienated are subdivided into personal, religious, and political grants, and grants for non-military service, most of the aliena- tions having been made between 16 18 and 1838. State or sheri lands are the Maharaja's personal holdings, and are managed by the revenue officers, who let them to the highest bidder for a term of years. The chief varieties of the ryotwari tenure are : the mirdsi, under which the payment of a fixed rental prevented the holder from eviction ; the upri, under which land can be given to a fresh holder after one or two years ; the dial khand, under which the holder pays a little more or less than the fixed rate ; and the vataiii, under which hereditary village officers hold lands for less than the usual assessment. The survey settlement, first introduced in 1886, is at present under revision. The assessment rates per acre in force are : ' dry crop,' from R. 1 to Rs. 4-4 ; rice land,

from Rs. 5-1 to Rs. 10; garden land, from Rs. 8 to Rs. 10. The revision survey up to the end of 1903 enhanced the total assess- ment by Rs. 91,77 r, or rii per cent.

The Kolhapur State proper had in 1903-4 a revenue of 44 lakhs, chiefly derived from land (12 lakhs), excise (i| lakhs), and Local funds (ii lakhs). The expenditure amounted to 43 lakhs, of which nearly 3 lakhs was devoted to the Maharaja's private expenses, 3 lakhs was spent on public works, and 2 on the military department. The revenue of the jdgirs is given in the table on p. 381. Opium, excise, and salt are under the control of the State. Since 1839, when the Kolhapur mint was abolished, the British rupee has been the only current coin. The Maharaja maintains a military force of 710 men. The strength of the police is 873 men, maintained at a cost of Rs. 80,000. The Central jail at Kolhapur had an average daily population of 243 in 1903-4, the cost per prisoner being Rs. 74. There are seventeen subordinate jails.

Of the total population 4 per cent. (7-7 males and 0-2 females) could read and write in 1901. Excluding a few missionary institutions, there were 250 schools in 1903-4, including a college, a high school, and a technical school. The total number of pupils on the rolls was 8,823, and the expenditure on education was about i| lakhs. The State possesses 15 libraries, of which the largest is in Kolhapur city, and 8 local newspapers. It also contains a hospital and 15 dispensaries, which treated nearly 168,000 patients in 1903-4, a lunatic asylum with 18 patients, and a leper asylum with 93 inmates. In the same year 21, 000 persons were vaccinated.

History

Rajaram II of Kolhapur

A brief biography

Abhijeet Patil, August 3, 2025: The Times of India

Had he lived a full life, Rajaram II of Kolhapur would have transformed his princely state. But the boy who became king at 16 was a man of many firsts by the time he breathed his last — aged just 20, several thousands of kilometres from home in Italy’s Florence.

Not only was he the first Hindu monarch to have travelled to Europe, overcoming the thencommon taboo over overseas travel, but he was also the first person to be allowed to be cremated in Italy. The only person known to have been cremated in Florence until then was British poet P B Shelley, 50 years earlier. In between, he was also witness to tech history: he was there to witness the first ever telegram to be sent to Britain from India.

Fortunately, he was a journal-maker, who meticulously noted down all that he saw and experienced during the 150 days he spent abroad. It’s from his diary that we now know how his stay and interactions in Europe filled his mind with many forward-thinking ideas — English education for all, compulsory schooling for girls, the necessity of a modern judicial system, industries, museums, research centres and banks.

The account he kept of what he saw and experienced during his stay came to life over 150 years later, when a digitised version of a book, based on his diary — first published in 1872 as ‘The Diary of Late Rajah Of Kolhapoor, During His Visit To Europe in 1870’ — surfaced a few years ago.

Raghunath Kadakane, Shiva ji University, Kolhapur’s head of the English department, translated the book — edited by British official Edward West, who was in the prince’s retinue — into Marathi on the monarch’s 155th birth anniversary.

MODERN DREAMS

Despite a history of rebellion, Kolhapur’s royalty had allied with the British “for the people”, Kadakane says. “Rajaram II had vision and was eager to modernise his state after his return,” he says. “His dreams were fulfilled by Rajarshi Shahu Maharaj, several decades later. Shahu Maharaj opened schools, built dams and developed a pro-people administration.”

Shahu Chhatrapati, the current head of Kolhapur’s royal

family and a Congress MP, says they have the original diaries of Rajaram II, but it is in a private collection.

Born Nagojirao Patankar, Rajaram II was adopted by the royal family of Karvir (Kolhapur), the descendants of Chhatrapati Shiva ji Maharaj. He was 16 in 1866 when he was crowned king of Kolhapur.

As the raja was a minor, political agent Colonel G S Andersen deputed West to run the administration. “A Parsee graduate of Bombay University was selected to carry out tuition and a scheme of education was carefully drawn,” West wrote.

Even during schooling, Rajaram II was a keen observer of Western customs, by which he was surrounded. He was housed in a residency far from the Kolhapur palace, growing up among Europeans.

Before he left for Europe, the 20-year-old Rajaram II laid the foundation of an English medium school, later named Rajaram High School.

SEEDS OF A VOYAGE

When the Duke of Edinburgh visited Bombay in 1870, none of the native princes who flocked to meet him attracted more attention than — and created as favourable an impression — as Rajaram II, West wrote. It was here that the seeds of a Europe voyage were sown.

The boy king began his journey with West, the Parsi tutor, 10 sevaks (staffers) and a hakim. West chronicles that Rajaram II was the first Hindu reigning prince to visit Europe.

WITNESS TO HISTORY

On June 23, Rajaram II witnessed the first telegraphic message sent from India to Britain.

“The Prince of Wales, the Duke of Cambridge, and many ladies and gentlemen were present. I was struck at seeing that the Prince of Wales received the answer to his telegram from the Viceroy of India in five minutes,” Rajaram II noted.

The next day, Rajaram II met Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. It was the first of his two meetings with her. Rajaram II also witnessed East India Association debates over cotton from India being exported to Britain. Dadabhai Naoroji helped him with insights. His itinerary included visits to Royal Society, Oxford University, where he interacted with the vice-chancellor; the Royal Academy; the coach factory; the silk factory; the British Museum; cotton mills; the Royal Theatre and other places.

DEATH IN FLORENCE & A SHELLEY CONNECT

From Britain, Rajaram II travelled to Florence in Nov, where his rheumatic condition worsened because of the chill. West brought in top Italian physicians to treat him, but he passed away on Nov 30. The last entry in his diary was poignant: about snowfall, which he saw for the first time in his life.

A cremation was not allowed since Italy was a Catholic state and forbade it. The only exception had been made some 50 years ago for Shelley, who had drowned on July 8, 1822, off the coast of Italy, when his boat sank during a storm, West wrote, adding that the question of the disposal of the Rajah’s remains after his death in accordance with Hindu customs gave rise to some difficulties because Italian law forbade it.

A POST-MIDNIGHT CREMATION

British minister Augustus Paget pushed for Rajaram II’s body to be cremated. The mayor of Florence, Signor Peruzzi, presented the matter before the council of ministers and permission was granted for a post-midnight cremation.

Early on Dec 1, Rajaram II was cremated in Cascine Park, on the banks of the Arno, with the Mugnone stream passing by. The municipality expected only a few to attend, but West recorded that a huge crowd had gathered, and security had to be arranged for.

Permission for cremation was granted only because Rajaram II had made a lasting impression on people he met in Europe, Kadakane says.

Shahu Chhatrapati notes why Rajaram II was a pioneer of sorts: he had a good education and was fluent in English and Western customs. Before him, a study trip to Europe had not been attempted by anyone in the lineage, and even his death on foreign shores did not stop his heirs from following in his footsteps. All heads of the royal family made such trips, he says. “I have visited Florence to see his memorial, which is well maintained by the local administration,” Chhatrapati says. “A bridge across the Arno, too, bears his name.”

Two years after his death, a “Monumento all’Indiano”, or a “Monument to the Indian”, was erected with a bust of Rajaram II under a cenotaph ( chhatri ) built in the Indo-Saracenic style.

West published Rajaram II’s diary after returning to Britain in 1883. He died in Naples in Italy, a few hours’ journey from Florence, where the Rajah he served was cremated.

1942, the Polish connection

Abhijeet Patil, Dec 18, 2022: The Times of India

From: Abhijeet Patil, Dec 18, 2022: The Times of India

Watching Poland exit the Fifa World Cup 2022 when they had reached the knockout stage after 35 years broke the hearts of Rajesh Kashikar and his family in Kolhapur.

Football’s popularity in this old city runs deep.

Cutouts and banners of players crop up during every major international tournament, and fans root for Brazil, Argentina and other heavyweight teams and superstars. But the Kashikars were sad because they have a blood connection with Poland that goes back to World War II.

A War-Time Romance

Rajesh’s grandmother Wanda Nowicka came to India as a 14-year-old among 5,000 Polish refugees who arrived between 1942 and 1948, and settled in Valivade village, a few kilometres from Kolhapur.

Love blossomed between Wanda and Rajesh’s grandfather Vasant Kashikar, a medical student at the time. Rajesh said his grandfather had to give up studyingmedicine as punishment for loving a Polish refugee, but they overcame everything.

“My late grandmother changed her name to Malati. She was a wonderful person who picked up Marathi and learnt to cook Maharashtrian food. She raised their five sons and grandchildren despite her heart’s yearning for her motherland. She visited her relatives in Poland several times. A couple of years ago we visited her brother’s son in Poland,” he said. Royal Patronage To Game While Vasant and Malati cemented their vows, some of the other Polish arrivals forged strong ties with the local men through football.

Impressed by London’s football clubs, Kolhapur’s Prince Shiva ji – Rajarshi Shahu Maharaj’s younger son – had introduced the game to the city in the 1920s. It thrived when the local teams began playing with foreigners, first with the British in 1936, and then with the Poles. Polish refugees started playing in Kolhapur’s clubs when the patrons saw the flair and technical knowledge they brought to the game. On Prince Shiva ji’s demise his elder brother – the future king Rajaram Maharaj – supported the game for a long time. Rajaram did not have a son, so on his death an infant boy, also named Shiva ji, was proclaimed his successor. As the new king was a minor, the British took control of Kolhapur state’s affairs and their agent, Lieutenant-Colonel Cecil Walter Lewery Harvey, formed a football team of the immigrants residing in Valivade’s refugee camp. But the boy-king Shiva ji died young and then Rajaram’s sister Radhabai, the rani of Dewas, came back to Kolhapur with her son Vikramsinh, who ascended the throne as Shahaji II and continued to support football. A book published by Kolhapur’s Practice Club in 1984 records that Colonel Harvey had chosen a few players from the club to play in Valivade’s Polish team. It also says Shahaji II founded a football team named ‘Palace’ that had foreign players from Practice Club.

Barefoot Footballers

Laxman Pise, now 88, grew up watching games between the Poles and local clubs. He was the first footballer to represent University of Pune in 1955. He said Polish footballers came to Kolhapur on Sundays and played friendly matches with local teams, and they played differently. “We were mostly barefoot.

We learnt from them that shoes are mandatory for the game. They also taught us skills and technicalities. We didn’t have coaches and the experience was enriching,” Pise said. Kolhapur’s football clubs are run through wrestling training centres called ‘talim’. A century ago there was no money and the clubs ran on pure passion. “We would walk along the railway track to reach Miraj for matches. We stayed in public buildings and one of us would bring food,” Pise said. His father Gopalrao Pise was a first-generation footballer from Kolhapur, and father and son played against each other during the inter-club game between Baraimam Talim Sangh and Balgopal Talim Sangh in the 1950s.

Gajanan Ingawale, 84, who played as centre forward for Shiva ji Talim Mandal, recalled a match between the Polish team and Shiva ji Tarun Mandal in the 1940s.

“We won the match but the Polish ’keeper stole the show. He had lost half his right arm, probably in the World War, and the spectators cheered him the most. Our players knew little about the game and tactics. We played barefoot with cloth wrapped around our toes to avoid injuries. We used to believe those who shoot the ball high and long are great players. The Polish players improved our game,” he said.