Coastline, beaches: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Cleanliness

2019: all- India; Kerala

U Tejonmayam, Nov 20, 2019: The Times of India

From: U Tejonmayam, Nov 20, 2019: The Times of India

From: U Tejonmayam, Nov 20, 2019: The Times of India

From: U Tejonmayam, Nov 20, 2019: The Times of India

From: U Tejonmayam, Nov 20, 2019: The Times of India

See graphics:

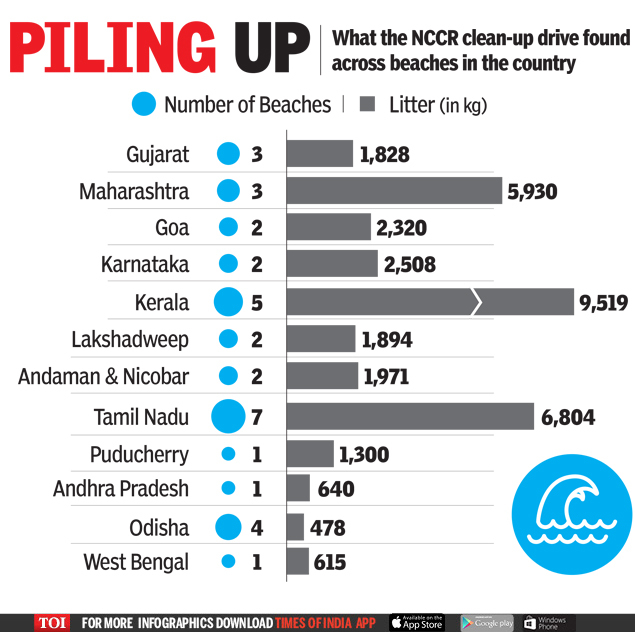

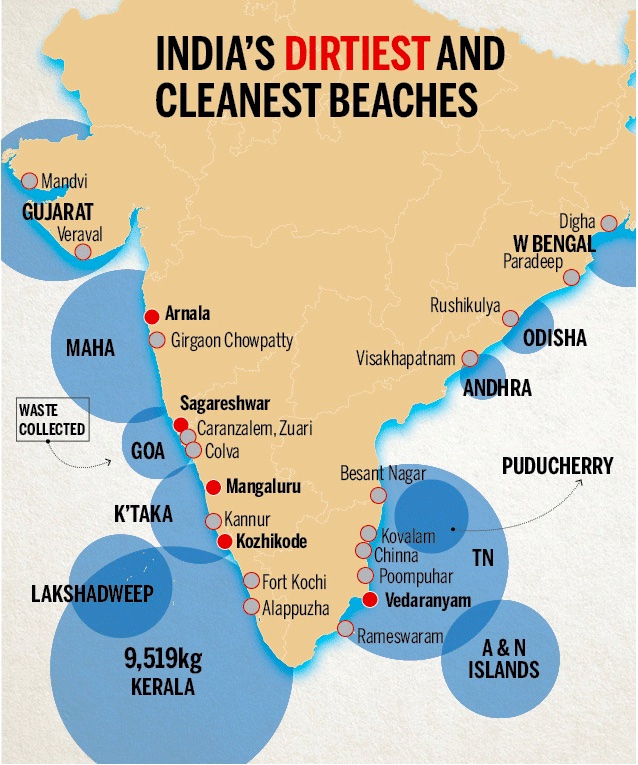

Litter on India’s beaches during a sample period in 2019.

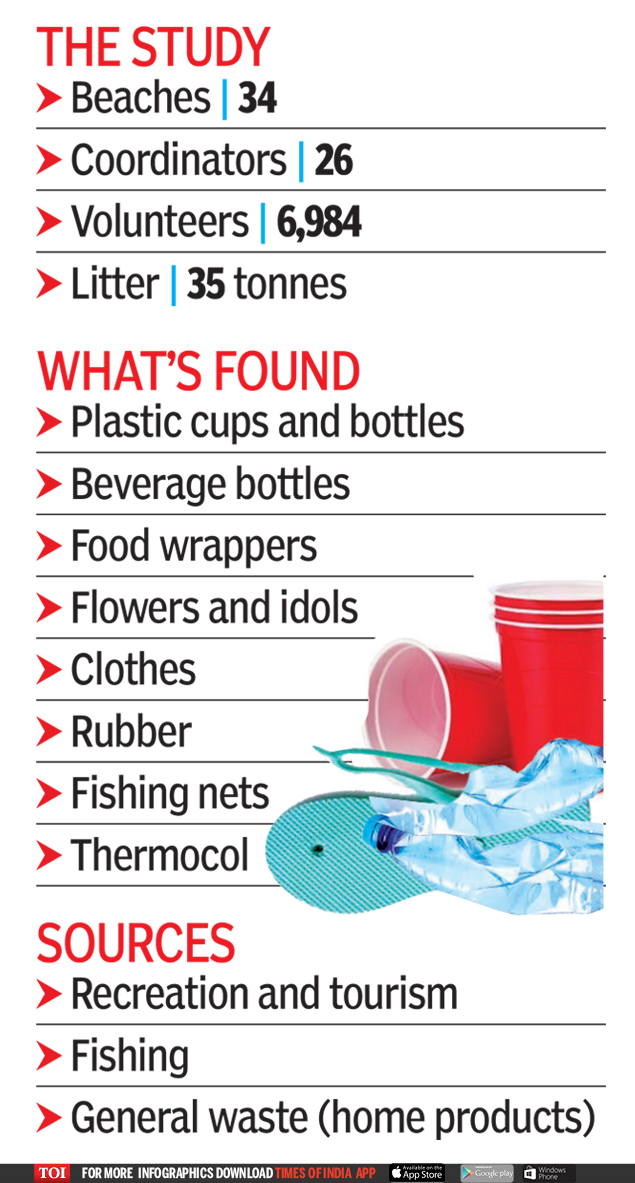

The 2019 NCCR study

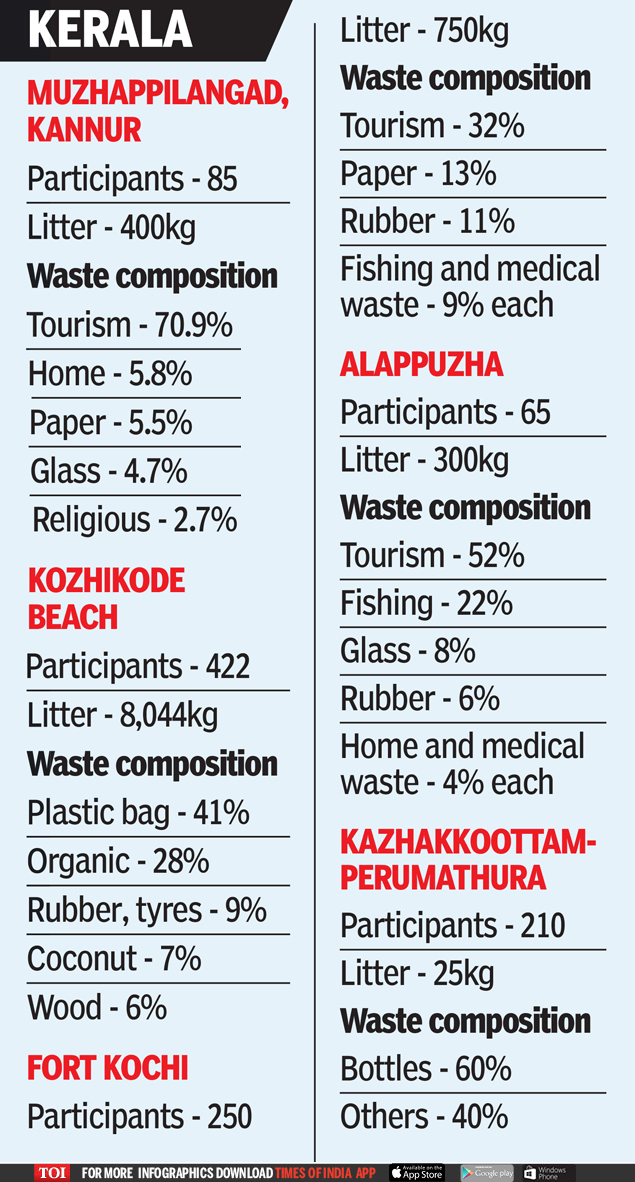

Litter on Kerala’s beaches during a sample period in 2019

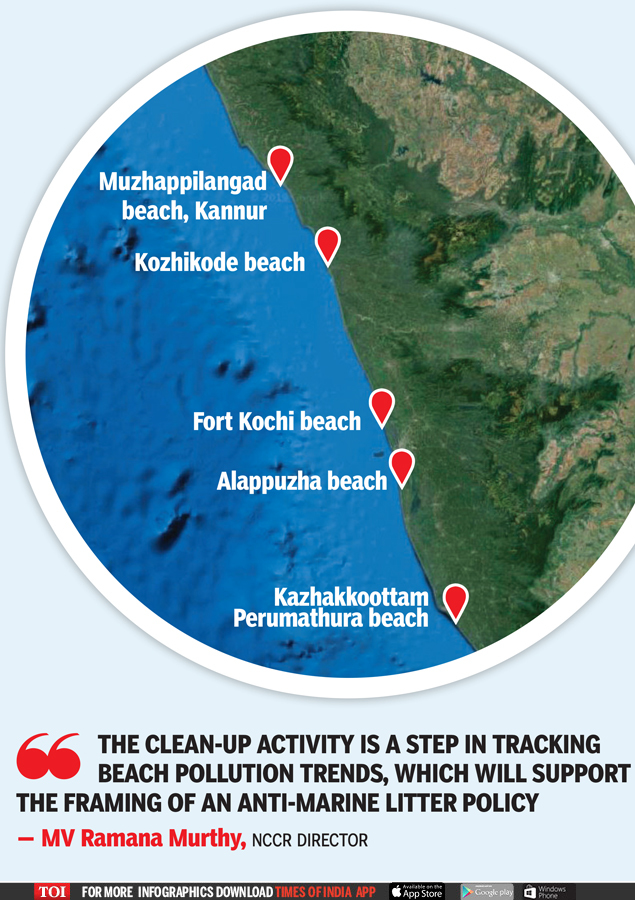

The beaches surveyed in Kerala

CHENNAI: Kerala’s sandy beaches and calm backwaters might be reeling under the pressure of too much tourism as 9,519kg of litter was collected from five beaches in just two hours during a coastal clean-up activity, making the coast the mostpolluted one in the country.

Volunteers, who were part of the activity conducted by MoES lab National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR) in September, collected 35 tonnes (2.39 lakh pieces of waste) across 34 beaches in India. Around 6,804kg of litter was collected from seven beaches in Tamil Nadu and 5,930kg from three beaches in Maharashtra. Odisha, where 478.2kg of garbage was collected from four beaches, had the leastpolluted coastline.

NCCR researchers said half of the litter collected was plastic, mostly dropped by beach-goers, while a portion of it was washed ashore. While the rest was waste from fishing activity along the coast and household items disposed in waterbodies linking the sea, around 20% was glass bottles.

“The major source of litter at 22 beaches is tourism and recreational activities. Plastic and glass were the major type. Plastic waste were cups and bottles, bags, bottle caps and food wrapper,” said the NCCR report. Plastic items may break down to microplastics (less than 5mm) during the weathering process. When this is swept into the sea, microplastics enter the marine food chain, settling in the gut and tissues of fish that are eventually consumed by humans.

“Other types of litter were glass bottles, footwear, tyres, gloves, organic waste, clothes, flowers and coconuts used for religious purposes,” said the report.

NCCR director MV Ramana Murthy said the clean-up activity was a step in tracking beach pollution trends which will support the framing of an anti-marine litter policy. It includes studying the type and quantity of litter generated on land, the quantity going to the coast and washed ashore and its impact on the ecosystem. “We will repeat this activity across the coast to collect more data that will equip us to speak about coastal pollution quantitatively,” he said. Of the 9.5tonnes collected in Kerala, around 8,044kg was picked up in Kozhikode south beach, which included 3,300kg of plastic bags. While tourism is a major source of litter, researchers said, the beach is polluted as streams join the sea. Wastes disposed in these streams reach the sea and some get pushed to the coast.

In Maharashtra, the main source of pollution was untreated sewage, industrial effluents and wastes from fish landing centres. “Beaches in big cities with larger population have more garbage. While there are regular cleaning efforts in Goa, beaches in states like Odisha are least polluted,” it said.

For researchers, the study also gave a glimpse of human behaviour. For instance, glass bottles, which could be liquor bottles, were picked up in several beaches. Around 60% of the 25kg waste (the least among the 34 beaches) collected at Kazhakkoottams Perumathura beach was liquor bottles.

Researchers said the study had several unanswered questions which they plan to pursue in future.

Part 2

U Tejonmayam, January 4, 2020: The Times of India

From: U Tejonmayam, January 4, 2020: The Times of India

From: U Tejonmayam, January 4, 2020: The Times of India

Thirty-four Indian beaches have together produced 35 tonnes of waste in a coastal cleanup operation conducted by professionals towards the end of last year. The litter recovered mostly comprised plastic and glass, paper, rubber and general waste left behind by tourists and local populace.

Table-topper Kerala’s sandy beaches and pristine backwaters are probably reeling under the weight of hectic tourism activity, as 9,519kg of litter, the highest in the country, was collected across its five beaches in two hours by volunteers, making it the most polluted coast in the country.

Volunteers, who were part of the operation conducted by Ministry of Earth Sciences lab National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR) in September 2019, picked up 35 tonnes or 2.39 lakh pieces of litter across 34 beaches. Around 6,804kg of litter was collected on six beaches of Tamil Nadu, the runner-up, while 5,930kg of waste came from three beaches of Maharashtra. Odisha, where 478kg of litter was collected on four beaches, has the least polluted coastline.

NCCR researchers said about half of the 35-tonne litter was plastic dumped by beach-goers looking for a whiff of fresh air. While the remaining trash comprised leavings of fishing activity and household items disposed in the sea, 20% of the waste was glass bottles.

“The major source of litter on 22 beaches is tourism and recreational activity. Plastic waste such as cups, bottles, bags, bottle caps and food wrappers were found,” said the NCCR report. Plastic items left on the beach generally break down into microplastics (less than 5mm) during the weathering process. When this is swept out to sea, microplastics enter the marine food chain and settle in the gut of fish eventually consumed by humans. “Other types of litter picked up were glass bottles, footwear, tyres, gloves, organic waste, clothes, and items such as flowers and coconuts used for religious purposes,” the report added.

NCCR director M V Ramana Murthy said the cleanup activity was a step in tracking beach pollution trends which will support framing an anti-marine litter policy. It includes studying the type and quantity of trash generated on land, the quantity reaching the coast, and its impact on the ecosystem. “We will repeat this coastal cleanup activity to collect more data to equip us to speak about coastal pollution quantitatively,” he said.

Of the 9.5tonnes collected in Kerala, around 8,044kg was picked up from Kozhikode south beach, which included 3,300kg of plastic bags. While tourism is a major source of litter, researchers said the beach in Kozhikode is polluted as small streams are directly linked to the sea.

In Maharashtra, the main sources of pollution were untreated sewage, industrial effluents and fish waste generated at fish landing centres. “Big cities with large populations have more garbage on their beaches... beaches in Odisha are the least polluted,” the report said.

For researchers, besides pollution, the study provided a glimpse of human behaviour. For instance, glass bottles, which could be liquor bottles, were picked up in several beaches including Tamil Nadu’s temple town Rameswaram. About 60% of the 25kg waste, the least among the 34 beaches, collected in Kerala at Kazhakuttom Perumathura beach was liquor bottles. “Glass bottles were found in Gujarat beaches too,” an NCCR researcher said. “In our ongoing study on fish, we have found pieces that disintegrated from fishing nets.”

Researchers said the study has left several unanswered questions which they have planned to pursue in future studies.

Garbage on Indian beaches: the extent of the problem, and types of waste

Coastal regulation zone (CRZ)

HC on shacks on beaches/ 2019

Murari Shetye , Oct 14, 2019: The Times of India

Resolving an over two-decade-old issue concerning the validity of shacks on beaches after the coastal regulation zone (CRZ) notification was enforced in the state, the high court of Bombay at Goa has held that temporary erections comprising bamboo and palm leaves are not constructions. As such, no ecological damage is caused due to beach shacks, it has noted, thereby ending the ongoing debate in the state whether a shack is a construction.

The order will have a significant impact on scores of cases filed before adjudicating authorities, seeking that shacks, which were claimed to be constructions on beaches, be demolished.

Specifying the meaning of construction, a division bench comprising Chief Justice Pradeep Nandrajog and Justice Mahesh Sonak on October 10 noted that the law prohibiting construction spoke of cement, brick and mortar structures having permanency, and that it could not embrace temporary erections using bamboo and palm leaves. “Generically, a construction is a cement, mortar and brick structure having permanency. Shacks are not constructed but are erected,” the HC observed.

The case pertains to a petition filed by members of the Anjuna village panchayat, who stated that 40 shops had been constructed within 200 metres of the high tide line (HTL) in a nodevelopment zone (NDZ) of the village. The Goa government will issue new licences for erecting shacks through a lottery system from October 17 onwards.

Coastal waters

Quality state-wise

From: Oct 18, 2024: The Times of India

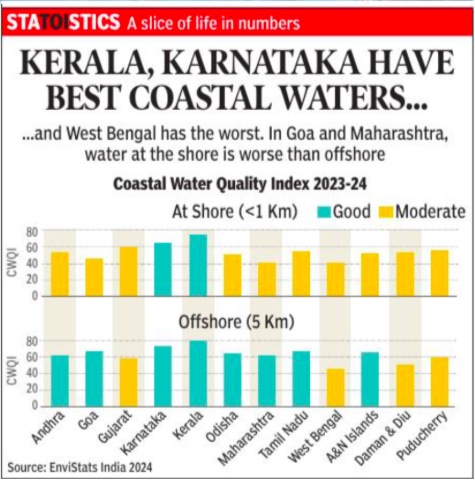

See graphic:

The Quality of Coastal waters, state-wise, 2023-24

Erosion

2024

From: Oct 19, 2024: The Times of India

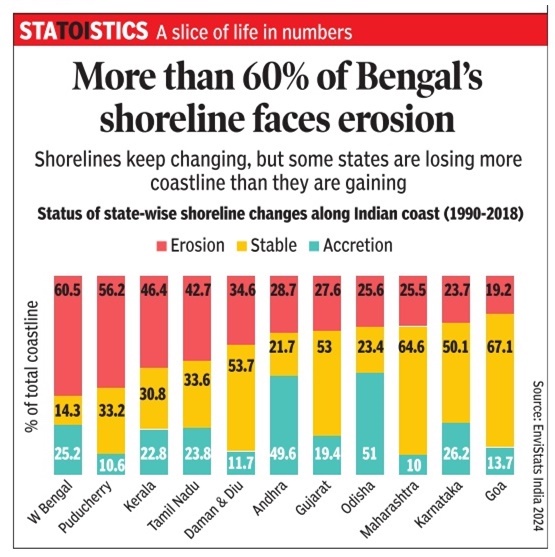

See graphic:

Erosion of the coastline in Indian states, as of 2024

State-wise

Kerala, 2024

Sudha Nambudiri, January 16, 2025: The Times of India

Beachcombing was synonymous with Sujith’s childhood in the sun-kissed shores of Shankumugham in Thiruvananthapuram. The beach was a magnet for family gatherings for shindigs on a sprawling stretch of ochre sand. The Indian Coffee House was an added bonus.

The lapping of waves against Kerala’s sandy shores once promised timeless beauty, often the backdrop of postcards and a favoured retreat for travellers. Fast forward to 2025, and the state’s idyllic be- aches are under siege, with Shankumugham shrinking to a mere patch in 30 years since Sujith’s playtime days.

Today, these shores tell a tale of relentless erosion, rising sea levels, the ravages of sand mining, and communities struggling to hold onto their seafront homes. Over 55% of Kerala’s 590km coastline is now “vulnerable to erosion”.

The affected beaches

Erosion threatens livelihoods and homes of more than 9.3m across 9 Kerala coastal dists

Two major studies in recent years, one by the National Centre for Coastal Research and another by the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services (INCOIS), have painted a stark picture of Kerala’s coastal future.

According to INCOIS, more than 300km of the state’s coastline fall into high and medium vulnerability categories, with some areas experiencing erosion at rates as high as six metres a year. This rapid erosion threatens not only the natural landscape but the livelihoods and homes of more than 9.3 million people spread across nine coastal districts.

In regions like Kannur, Kochi, Alappuzha, and Kasaragod, the encroaching sea is a daily reminder of vulnerability. Beaches in Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam, Malappuram, and parts of Thrissur have already vanished or are in the process of disappearing.

This accelerating loss is exacerbated by the warming Arabian Sea, which has led to an increase in cyclonic events and sea surges, particularly from May to Aug, with a peak in June and July.

PARADISE TO PERIL

The human cost of this environmental crisis is immense. Many coastal communities have been displaced, their homes swallowed by the sea, leaving behind a trail of economic and emotional distress.

For as long as anyone can remember, fishing communities along Alappuzha’s coast have lived by the saying “Kadalamma chatikkilla” — the sea mother won’t deceive. But as the shoreline erodes, that ancient faith is faltering. Sand mining, the silent thief, has stripped the beaches, forcing many to abandon their ances- tral homes. Over 600 houses have crumbled into the sea’s maw, and poverty grips the fisherfolk tighter each day.

“I know no life but fishing,” said Kalesh, a fisherman from near Thottappally harbour, watching the sea that once nurtured his community now gnaw at it. His parents live next door in a house built after the 2004 tsunami swept away their old one, but even this home bears the scars of erosion. “The catch has dwindled,” Kalesh’s mother Sura said. “And there’s no beach left to haul our boat ashore.” Their blue boat rests awkwardly in their yard, a silent testament to the changing tides.

K C Sreekumar from Alappad recalled a time when the coastal stretch from Azheekkal to Vellanathuruth spanned 89sq km in 1955. By 2004, it had shrunk to a mere 7sq km. The once thriving Alappad market, where small ships anchored, is now a shadow of its former self, as the sea continues its relentless advance. Many families have been forced to relocate, some never returning to their original homes. Others, constrained by financial limitations or fear of starting anew elsewhere, have chosen to stay, clinging to what remains of their lives along the coast.

Businesses dependent on tourism are struggling to stay afloat. Aneesh, who runs Jeevan Beach Resort in Kovalam, said: “Earlier, the beach had a width of 30m. Now, it is only 10m and hasn’t been restored fully for the past two years. It affected the inflow of tourists, especially foreigners. Now, they come and check out the very next day. Earlier, they used to stay here for three months. Kovalam has lost its glory.” The waves have “swallowed the walkway” and tourists are vanishing, leav- ing local business owners like Senthil K, Jose Franklyn and Biju to struggle with plummeting sales. “My sales have dropped by 70%,” souvenir shop owner Senthil said. The once “vibrant spot” is now deserted, prompting desperate calls for urgent govt action to “ save the beach and our businesses”.

COASTAL CRISIS DEEPENS

Kerala University of Fisheries and Ocean Studies (KUFOS) recently highlighted the scale of the crisis. From 2012 to 2021, the state experienced 223 sea surge events, with Alappuzha facing the highest number at 105, followed by Ernakulam (64) and Thrissur (54).

Central Kerala, the hub of marine trade and tourism, is particularly vulnerable, experiencing an average of 12 hazard events for every 10km. Areas such as Eriyad, Azhikode, Chellanam, Ambalappuzha, Purakkad, Kuzhupilly, and Vadanapilly are now categorised as high-hazard zones due to a combination of sea surge inundation, sea-level rise, and severe erosion.

“South and central Kerala are more susceptible because of their sandy coasts, unlike the rocky shores in the north,” said Girish Gopinath, head of climate variability and aquatic ecosystems at KUFOS.

The primary reasons cited for these changes are inadequate scientific planning of coastal infrastructure and the effects of climate change.

More than 50% of Kerala’s coastline is lined with artificial structures such as groynes, various types of seawalls and fishing harbours, in addition to ports. Groynes typically consist of wooden or concrete barriers, built perpendicular to a shoreline to prevent erosion, trap sand, and protect beach- es from the impact of waves and tides.

However, such structures have proved counter-productive, particularly in the south, where sediments are often washed away by littoral currents that flow parallel to a shoreline. According to Gopinath, this structural interference with natural sediment flows has intensified erosion, leaving areas like Cherthala and Ponnani exposed to the sea’s relentless encroachment.

“There is a phenomenon where seawater overtops into the shore, bringing with it large amounts of sediment. Unfortunately, due to choked and encroached canals, there is no way for the water and mud to flow back, exacerbating the problem,” he said.

Kerala University geology professor E Shaji pointed to the acute shortage of sediment supply from rivers, exacerbated by dredging, sand mining and sediment trapping by dams, as a major contributor to the problem. “It would take at least five years to revive a beach,” he said.

As Kerala battles against nature and neglect, experts agree that an aggressive coastal management plan is critical. Without swift and coordinated action, the state’s once-pristine beaches could be lost to history. Senior scientist K K Ramachandran emphasised the need for precise and up-to-date data to guide coastal development and conservation, ensuring that interventions are based on accurate tracking of erosion and accretion. “Only a handful of projects use the latest data. We require a year’s worth of data before proceeding with building any structures,” said consultant at National Centre for Earth Science Studies. (Inputs from M K Sunil Kumar, T C Sreemol, Jaikrishnan Nair, Krishnachand K)

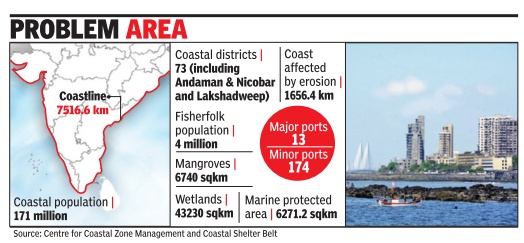

Indian coastline under threat

The Times of India, Aug 05 2015

Subodh Varma

Cash-strapped authorities put coastline under threat

Construction, erosion top worries: Panel

India's 7500 km long coast line, home to over 171 mil lion people, is under threat and the government machinery meant to manage it is in disarray . The coastal zone management authorities (CZMA 's) at the national and state level are orphaned bodies with no financial support, except what they raise by charging fees from those wanting project clearance. They are packed with ex-officio bureaucrats from various departments with limited expertise.Their meetings are spent in discussing project applications. They clear 80% of projects but never go back to monitor or check violations. They don't have maps with requisite details. They have not even marked out the high tide line.

These are the shocking findings of a report prepared by a group of environmental activists cum experts from the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi and the Namati Environmental Justice Program. The authors interviewed sitting and ex-members of the CZMAs, analysed minutes of 350 meetings of the CZMAs and looked at high court and National Green Tribunal cases over the years.

By a 1991 government notification, the coast is divided into four zones -one stretches over the water while three stretch landwards going up to 500 meters from high tide level. Multiple, contesting us es are vying for a piece of the coastindustries, real estate, tourism, livelihoods, mining and conservation, says Meenakshi Kapoor, one of the researchers.

“There are threats from unregulated construction, discharge of untreated effluents and sewage, destruction of mangroves, deterioration of critical ecosystems such as estuaries, saltpans, coral reefs, etc and coastal erosion,“ she said.

In most coastal Indian cities, poorer sections are forced to live in slums on the coast. Municipal authorities allow destruction of natural drainage and wetlands, as in Mumbai, causing flooding.Over 90% of sewage pouring into the sea from 87 big cities is untreated.

It was to regulate and monitor these threats that the coastal zones were notified and CZMAs were set up. On paper there are strict rules about where you can build a hotel or an ice factory , and where you can have fish processing units or net mending yards. And, the CZMAs are supposed to keep a tight watch. But the reality is reverse.

The report narrates in harrowing detail their analysis of 350 meeting minutes of national and state CZMAs. The NCZMA discussed 157 agenda items between 2003 and 2013 of which 73 related to reclassifying a piece of the coast so that it can be used differently . Just 12 cases of violations and just one case of reviewing what the state CZMAs were doing was discussed.

The state CZMAs were initially given Rs 5 lakh each by the central environment ministry . After that they have been left to their own de vices till 2011 when state governments were asked to fund them. Meanwhile each state CZMA has hammered out its own way of raising funds.

In Goa, if you want to set up a commercial institution, you apply to the Goa CZMA and pay Rs 10,000 fees. For setting up anything worth upto Rs 5 crore, you pay processing fees of Rs 25,000 in Gujarat, Rs 1 lakh in Maharashtra or just Rs 10,000 in West Bengal. Since the money is coming from project proposals, maximum time is spent by the state bodies discussing them. In Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Odisha, over 90% of the agenda items were project proposals.

In other states, this frequency was between 60 to 80%, with only Goa having 46% frequency , according to analysis of meeting minutes between 2010 and 2013.

The report recommends an overhaul with better definition of roles and powers, more resources, participatory planning, bringing in transparency , and improving monitoring and compliance. Otherwise, this bureaucratic mess will be unable to save India's coasts.

Average sea level rise of 1.7mm/year

Vishwa Mohan, Nov 20, 2019: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, Nov 20, 2019: The Times of India

Sea levels along the Indian coast have risen by 8.5 cm during the past 50 years with an average increase of 1.7 mm per year, said the government in Rajya Sabha as it shared data from 10 major ports across the country in response to a Parliament question.

Compared to global data, the annual average seal level rise along Indian coast is almost half at present. UN’s latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report shows that sea level globally is rising at the rate of 3.6 mm per year and “accelerating”.

The data, collected at 10 Indian ports, indicates sea levels at Diamond Harbour in West Bengal recorded highest annual average increase (5.16 mm/year) followed by Kandla (3.18m/year) in Gujarat, Haldia (2.89 mm/year) in West Bengal, Port Blair (2.2 mm/year) in Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Okha (1.5 mm/year) in Gujarat. These annual average figures were not taken during the same period or for same duration at all ports. Even though the data may not be exactly comparable, but experts say they give a fair idea of sea level rise as figures were recorded over a longer period ranging from 28 years to 128 years.

The government in its response, said the rate of increase of sea level can’t be attributed to climate change “with certainty” as no long term data on land subsidence or emergence are available for these locations. Junior environment minister, Babul Supriyo, told Rajya Sabha that the highest rise of sea level increase at Diamond Harbour was also due to large-scale land subsidence seen happening there. The same may apply to Kandla, Haldia and Port Blair, he said. The figures, cited by him, were taken from ministry of earth sciences.

Soil erosion

Ashis Senapati, May 23, 2021: The Times of India

COASTLINES LOST DUE TO SOIL EROSION

Almost one-third of India’s 6,632km coastline was lost to soil erosion between 1990 and 2016

In the past three decades, east coast was the worst affected due to cyclonic activities from Bay of Bengal

West Bengal (63%), Puducherry (57%), Kerala (45%), Tamil Nadu (41%) most suspectible to erosion

Source: National Assessment of Shoreline Changes along Indian coast

Length of coastline

State-wise

Oct 16, 2024: The Times of India

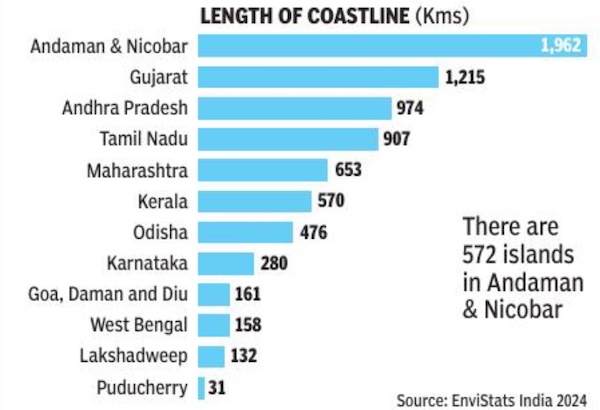

Andaman & Nicobar coastline is 60% more than Gujarat’s, the state with second highest access to sea

From: Oct 16, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

The length of the coastlines of Indian states

As of 2025

Umamaheswara Rao, January 4, 2024: The Times of India

Visakhapatnam : India’s coastline expanded by 47.6% in just over five decades — from 7,516km in 1970 to 11,098km in 2023-24 — with states like West Bengal, Gujarat and Goa adding significantly to their shoreline, according to an MHA report based on new terms of reference for measuring coastal accretion and erosion.

Gujarat’s recalculated coastline contributed the most to this growth — from 1,214km in 1970 to 2,340km in the past 53 years. West Bengal’s was the highest rise in percentage terms — up 357% to 721km.

Experts: Refined method gives correct idea of coastline length

This upward revision of coastline length across nine states and UTs is attributed primarily to using a new methodology to measure India’s maritime parameter, as established by National Maritime Security Coordinator. Unlike older methods that relied on straight-line distances, the scientifically updated approach incorporates the measurement of complex coastal formations such as bays, estuaries, inlets, and other geomorphological features. According to experts, this refined methodology provides a more precise representation of the true length of the coastline, capturing its dynamic and heterogeneous characteristics. Coastline data from 1970, as reported by National Hydrographic Office and Survey of India, was based on the measurement techniques and technologies available at the time.

While Gujarat retains its position as the state with longest coastline, Tamil Nadu, with a revised length of 1,068km (previously 906km), has overtaken Andhra Pradesh (1,053km), based on new survey.

Puducherry’s coastline — including Karaikal, Yanam, and Mahe — contracted by 4.9km, marking a departure from the upward revision elsewhere. Kerala reported the smallest increase, adding 30km (5%) to its coastline.

The data cited in the MHA report are still under review. India’s coastline spans the mainland and several islands, bordered by the Bay of Bengal to the east, the Indian Ocean to the south, and the Arabian Sea to the west. Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, TN, AP, Odisha, and Bengal, and four UTs — Daman & Diu, Lakshadweep, Puducherry, and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands — constitute the country’s maritime economy and biodiversity. AP has been developing new ports such as Ramayapatnam, Krishnapatnam, and Kakinada Gateway, all of which are expected to boost economic activity, employment, logistics, industrialisation, and urbanisation.