President’s rule: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

President’s rule in India

1951-2025 Feb

Anjishnu Das, Aug 29, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Anjishnu Das, Aug 29, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Anjishnu Das, Aug 29, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Anjishnu Das, Aug 29, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Anjishnu Das, Aug 29, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Anjishnu Das, Aug 29, 2023: The Indian Express

Punjab has experienced long durations under President’s Rule in the past, including 302 days when it was used the first time ever in 1951, after infighting in the Congress led to the state government’s collapse.

After President’s Rule has been imposed, both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha must ratify it by a simple majority within two months. The Constitution requires President’s Rule to be renewed every six months by Parliament, and it can be revoked by the President at any time.

Here’s a look at the history of President’s Rule in numbers.

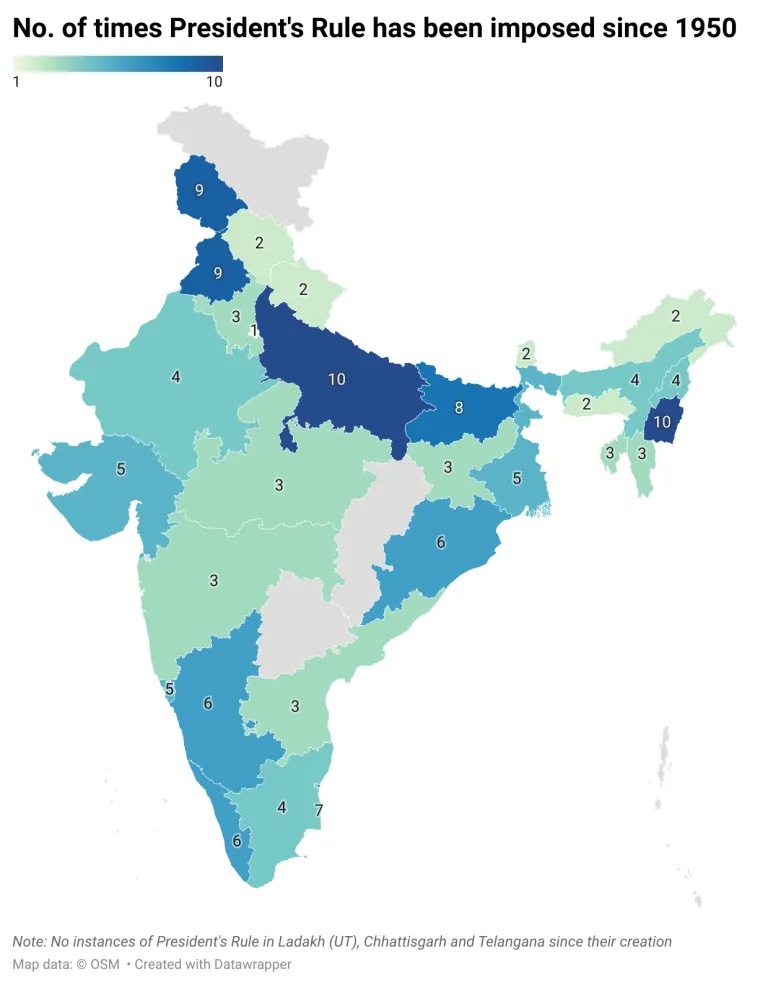

Manipur, UP saw President’s Rule most frequently

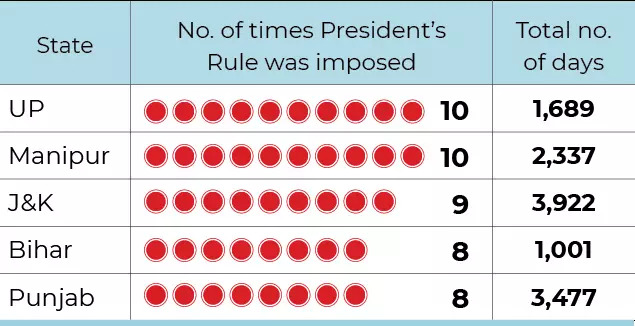

Incidentally, Manipur and Punjab have seen among the most instances of President’s Rule since Article 356 was enshrined in the Constitution in 1950, according to data published by the Lok Sabha Secretariat. Manipur is tied with Uttar Pradesh for the most frequent imposition of President’s Rule, at 10 each. Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir follow with 9 each. Since 1950, President’s Rule has been imposed a total of 134 times across 29 states and UTs.

In 1977 alone, there were 14 impositions of President’s Rule following a two-year period of Emergency under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. After the Morarji Desai-led Janata Party government defeated the incumbent Congress to win a majority in the 1977 Lok Sabha elections, it dissolved 9 state assemblies citing the electorate’s “lack of confidence” in the state governments. Following the general elections in 1980, in which Indira Gandhi returned to power, she, too, dissolved state Assemblies and imposed President’s Rule in the same 9 states, after claiming the state governments no longer represented the electorate.

The next highest instances of President’s Rule came in 1992 at 6, of which 4 occurred in UP, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh due to communal violence following the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, UP.

Since 1950, President’s Rule has been imposed at least once a year in 53 out of 74 years. The 1960s and 1970s saw the most frequent use of President’s Rule. The provision has been applied considerably less frequently since then.

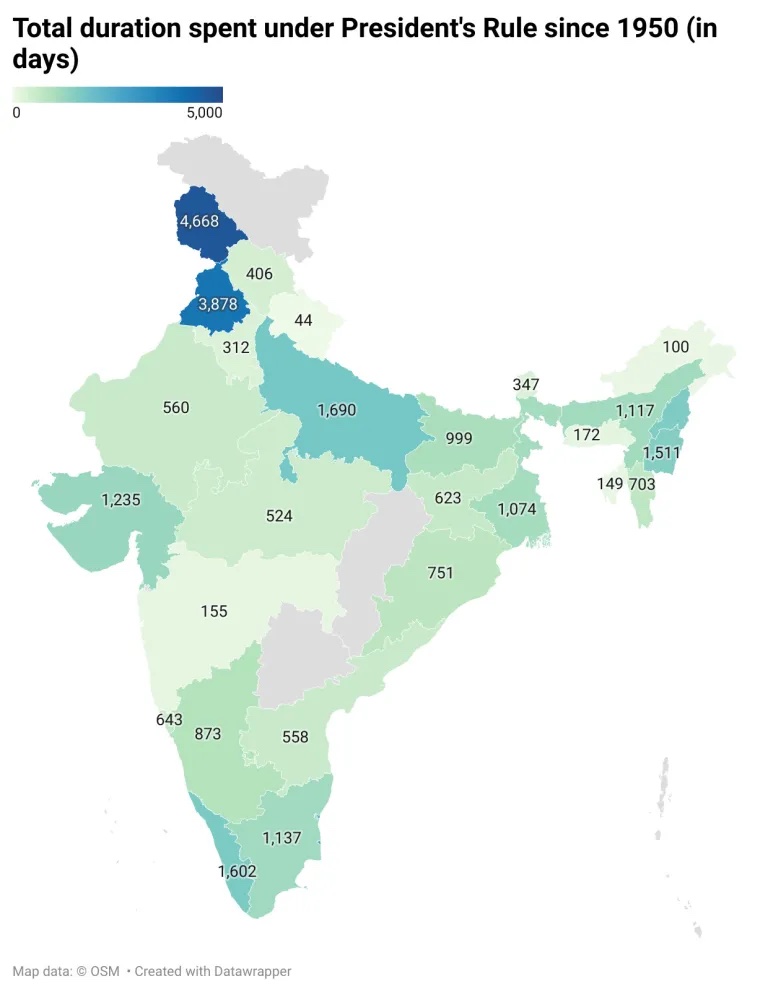

Nearly 13 years of President’s Rule in J&K, over 10 in Punjab

Jammu and Kashmir and Punjab have seen the longest durations spent under President’s Rule, at 4,668 days (12 years, 9 months) and 3,878 days (10 years, 7 months), respectively, owing to the recurring spells of militant and separatist activity, and unstable law and order situations in both regions.

Puducherry, at 2,739 days or 7.5 years, saw the third longest duration of President’s Rule. The UT saw repeated cases of governments losing support in the Assembly due to infighting among coalition partners or defections. The most recent instance of President’s Rule was also in Puducherry in 2021, after the Congress-led government lost power in a vote of confidence.

Despite experiencing the highest number of separate instances of President’s Rule, UP and Manipur saw shorter durations, at 1,690 days (4 years, 7 months) and 1,511 days (4 years, 1 month), respectively. Only 8 states and UTs have seen less than a year of President’s Rule in total. Uttarakhand, a relatively new state, has spent just 44 days under President’s Rule, in 2016.

States and UTs have cumulatively seen 30,478 days under President’s Rule. On average, each instance of President’s Rule in India lasted 228 days (or more than 7 months).

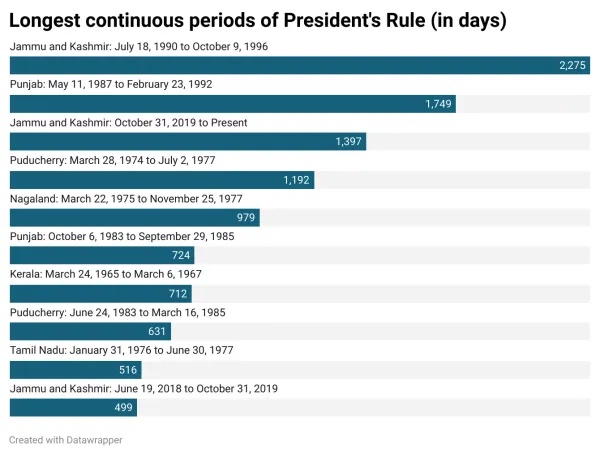

At more than six years, J&K saw the longest single period under President’s Rule between 1990 and 1996, when heightened militancy led to communal violence and the mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits. The next longest President’s Rule was in Punjab for almost five years between 1987 and 1992 amid increased terrorist activity. The third longest – at 1,397 days – and the only currently active President’s Rule is in J&K, which has been without an elected government since 2019 after its special status was revoked and it was bifurcated into two new UTs.

At that point, J&K had already been under Governor’s Rule since June 2018 after the BJP withdrew its support to the Peoples Democratic Party-led government. Under the now-scrapped special provisions for J&K, on imposition of Article 356, the state went under Governor’s Rule (with the assent of the President), which could last up to six months, followed by President’s Rule.

The shortest duration of a President’s Rule has been 7 days, occurring on three occasions – in West Bengal (1962) after the death of CM Bidhan Chandra Roy, in Karnataka (1990) when communal violence led to the dissolution of the Assembly, and in Bihar (1995) to enable the passage of a vote-on-account for government expenditure until the results of Assembly polls were announced.

President’s Rule used 88 times under Congress, 51 times under Indira Gandhi alone

Since 1950, across the tenures of all six Congress Prime Ministers, President’s Rule has been imposed 88 times for a cumulative duration of 22,037 days. Congress governments imposed President’s Rule at a rate of just over three times every two years with an average duration of 250 days for each instance. In comparison, the Janata Dal and its offshoots imposed the longest average President’s Rule, at 347 days, despite the party being in office for just over three years. The BJP, during the nearly 16 years it has been in power at the Centre, has imposed President’s Rule at a rate about once per year, with an average duration of 180 days.

Barring I K Gujral, each of India’s 14 Prime Ministers has imposed President’s Rule during their tenures at least once. Indira Gandhi’s nearly 16 years in office saw President’s Rule implemented 51 times for a cumulative 12,943 days across states and UTs – the highest figures among all PMs. Though Jawaharlal Nehru was the longest-serving PM, for nearly 17 years, under him, President’s Rule was implemented just seven times. Despite their tenures lasting less than a year, the Janata Party’s Charan Singh (1979-1980) and the Janata Dal’s Chandra Shekhar (1990-1991) saw President’s Rule implemented five times each, the same number as Atal Bihari Vajpayee in his total of six years as the PM.

1976-1996

From: January 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Jan 12, 2022: The Times of India

See graphics:

The longest and shortest single spell of President's rule, 1976-1996

No. of times President's Rule was imposed, state-wise

The impact on the politics of the state concerned

As of 2025

ANJISHNU DAS, Sep 21, 2025: The Indian Express

An analysis shows that since Independence, President’s Rule has been invoked 135 times, starting with 1953, and that after its revocation, the party in power before its imposition was dethroned 87 times. Of these, 69 times followed fresh elections. In other words, nearly two-third of the time, a new party came to power after revocation of President’s Rule.

Punjab (including when parts of it were known as the Patiala and East Punjab States Union or PEPSU) has seen the most instances of the state government changing hands after President’s Rule was revoked, at seven. From the early 1970s to the late 1980s, power mostly alternated in the state between the Congress and Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), which had the BJP as its ally, then, as they were the two dominant parties before the rise of the Aam Aadmi Party.

While Punjab saw relatively short stints of President’s Rule early on owing to political instability, it saw the longest spells in the 1980s and 1990s during the peak of militancy. Altogether, Punjab has been under President’s Rule nine times, for a total of 3,878 days, second only to J&K at 4,668 days.

In terms of the total number of times, Manipur has seen the most stints of President’s Rule, at 11, followed by Uttar Pradesh at 10. While Punjab, J&K and Manipur all fought periods of militancy, in UP, it was political instability that led to President’s Rule.

After Punjab, it is Manipur that has seen the most political shifts after periods of President’s Rule, at six times. The Congress came to power four of those times, replacing the previous ruling party or coalition. All four of these times, the previous governments fell due to resignations or defections, leading to a loss of majority in the Assembly. The other parties that came to power in this manner in Manipur were the Janata Party and the Manipur People’s Party.

President’s Rule and government changes

President’s Rule was first imposed in Manipur in 1967, ahead of elections to the then Union Territory’s first-ever Assembly. The Congress came to power with a narrow majority of one, with 16 seats in the 30-member House. Then the Speaker belonging to the Congress resigned, leaving no party with a majority. After the government collapsed, the Assembly was kept in suspended animation. By 1968, the Congress was able to form the government again without fresh elections, bringing an end to President’s Rule.

In 1972, President’s Rule was imposed for the third time in Manipur after a statehood movement turned violent. Manipur became a full-fledged state that year and in the ensuing Assembly elections, the former Congress government was ousted by a Manipur People’s Party-led coalition.

In 1977, in the post-Emergency elections where the Congress was swept out of power, the Janata Party also came to power in Manipur, after a series of defections in the Congress led to a collapse of the government and the imposition of President’s Rule. Several Congress-ruled Houses across the country were similarly dissolved by the Janata Party government.

In 1979, the Janata Party government in Manipur fell amid rising discontent within the party and corruption charges, and President’s Rule returned. In the ensuing 1980 Assembly polls, the Congress returned to power.

Uttar Pradesh and Puducherry have seen governments change six times each after President’s Rule, while Gujarat and J&K have seen such a change five times each, and Bihar, Karnataka and Kerala four times each.

Kerala was also the first state to get a non-Congress government in 1957, after the E M S Namboodiripad-led CPI came to power dethroning the Congress after a period of President’s Rule.

In 25 instances when the Assembly was dissolved despite the ruling party or coalition holding a majority, the party in power got replaced after President’s Rule. Ten such instances came in 1977, when the Janata Party government at the Centre dismissed several state governments after the Congress lost power. In 1980, when the Congress returned to power, it in turn dismissed eight state governments despite the fact that they held majorities in the Assembly.

Of the 10 states in which it dismissed state governments in 1977, the Janata Party came to power in eight, with regional parties forming the government in two. The Congress came to power in all the eight states where it dissolved the Assemblies in 1980.

In 10 cases where a different party came to power after President’s Rule was revoked, the previous governments had been dismissed owing to violence or a breakdown of law and order.

For instance, in 1992, the governments of UP, Himachal Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh were dissolved in the wake of the demolition of the Babri Masjid. In each of these states, the BJP lost power in the elections held after President’s Rule was revoked. Similarly, Manipur, Assam, Punjab and Nagaland, where President’s Rule was imposed over violent insurgencies, saw change of government after it was lifted.

Supreme Court rulings

1959-2005

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Dec 2, 2019 The Times of India

The BJP-led Centre’s ridiculous midnight shenanigans through a pliant governor in BS Koshyari to prevent the Shiv Sena-NCP-Congress alliance from forming government in Maharashtra failed, thanks to CJI SA Bobde’s prompt action to list their petition and an expeditious direction for floor test by a Supreme Court bench led by Justice NV Ramana. A “murder of democracy” was prevented. It exposed the hollowness of BJP’s almost proprietorial claim over the political moral high ground.

Congress protested the loudest and rightly berated BJP for the mess. But it was a Congress government headed by Jawaharlal Nehru which misused the power under Article 356 of the Constitution to sow the “murder of democracy” seed in Kerala in 1959. The seed has grown into a thick weed, chocking the ethical exercise of Article 356.

The EMS Namboodiripad government in Kerala was guillotined in 1959 by the Centre at the behest of then governor B Ramakrishna Rao. Since then, it has been repeated umpteen times. The most sinister one happened on August 15, 1984. The Indira Gandhi government, through governor Ram Lal, dismissed the TDP government in Andhra Pradesh headed by NT Rama Rao, when he was away in the US for coronary bypass surgery.

On his return, Rao herded his MLAs and sent them to Bengaluru in luxury buses, a practice now adopted by many political parties. Then he went to the people’s court riding his ‘Chaitanya Ratham’. Public outcry forced the Centre to reinstate NTR.

The Janata Party government headed by SR Bommai was dismissed by Rajiv Gandhi on April 21, 1989, through governor Pendekanti Venkatasubbaiah, who rejected Bommai’s written request for test of strength in the assembly. He moved the SC and its judgment has become the touchstone for testing the validity of Centre’s actions, through governor, to ‘murder democracy’.

Prior to Bommai, the Centre’s might under Article 356 to ruthlessly dismiss non-Congress governments was taken as inevitable, attracting muffled criticism from political analysts, who in general leaned towards Congress’s hereditary right to be in government.

The Bommai judgment [1994(3) SCC 1] severely truncated gubernatorial discretion to recommend dismissal of state governments and lain down that ‘floor test’ was the sole mechanism to determine who enjoyed majority support. But the nine-judge ruling has not been able to curb the tendency of political parties in power to ‘murder democracy’. Two such brazen ‘murders’ took place in 2005 in Bihar and Jharkhand under the UPA government led by Manmohan Singh.

While arguing Maharashtra’s case, senior advocate and Congress leader AM

Singhvi said “democracy is a game of numbers”, a reiteration of the 25-year-old Bommai judgment. Yet, governments at the Centre continue to contemptuously disregard numbers and perpetrate ‘murder of democracy’.

Through a midnight operation in 2005, the Centre aided by governor Buta Singh dissolved the Bihar assembly to prevent the NDA, which was on the brink of cobbling a majority in a hung House, from staking claim to form government. The governor’s May 22, 2005, report recommending dissolution of assembly was accepted by the Union cabinet at 11 pm. Then President APJ Abdul Kalam was away in Moscow. The decision was faxed to him in Moscow at 1.52 am on May 23. The President’s approval was faxed back at 3.50 am. The SC had criticised the manoeuvres of the Centre and the governor and had declared imposition of President’s rule unconstitutional [Rameshwar Prasad case, 2006 (2) SCC 1].

The actions of Koshyari and the Modi government in Maharashtra mirror the dark deeds of the Manomohan Singh government and governor Buta Singh in Bihar in 2005. That year, Jharkhand governor Syed Sibtey Razi, on the Centre’s instructions, installed JMM leader Shibu Soren as CM despite the NDA claiming support of 41 MLAs in the 80-member House. SC followed the Bommai judgment and ordered floor test. Soren lost. NDA’s Arjun Munda became CM.

In all these and many more instances, governors have always adopted a ‘more loyal than the king’ approach despite a 40year-old SC judgment telling them to act independently [Hargovind Pant vs Dr Raghukul Tilak, 1979 (3) SCC 458]. “It is no doubt true that the governor is appointed by the President which means in effect and substance by the government of India, but that is only a mode of appointment and it does not make the governor an employee or servant of the government of India,” the SC had said.

A person’s political stripes seldom vanish. Governors, most of whom are politicians in the sunset of their careers but with unflinching loyalty towards the party in power, have never questioned the Centre’s instructions seeking recommendations for dismissal of state governments.

BR Ambedkar had reposed blind trust in constitutional morality of governors and presidents. A trust that made him brush aside Constituent Assembly members’ grave apprehensions about misuse of Article 356.

He had said, “Proper thing we ought to expect is that such Articles (like 356) will never be called into operation and that they would remain a dead letter. If at all they are brought into operation, I hope the President, who is endowed with these powers, will take proper precaution before actually suspending administration of the province.” Ironically, Ambedkar had also said that a good constitution could turn bad and a bad constitution could turn good, depending on the character and morality of people entrusted with its implementation.

1977-2016

The Times of India, Apr 22 2016

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Showing increasing intolerance towards Centre's use of Article 356 to dismiss state governments, the SC has clarified in several judgments that Central rule was no substitute to testing a democratically elected government's strength on the floor of the assembly .

In 1977, then Janata Party government asked CMs of nine Congressruled states to resign or face dismissal through Article 356. This was challenged in the SC, which took a lenient view of the political manoeuvring. It said judicial review of presidential proclamation was on a limited ground and couldn't touch political aspects.

But the judiciary started taking a stern view of Article 356's misuse after overturning the Centre dismissed S R Bommai in Karnataka and the Meghalaya government in 1989 and 1991. By the time the court took up the challenges to Central rule in Karnataka and Meghalaya, the Centre had dismissed the governments of UP , MP and Rajasthan in 1993 after the Babri masjid demolition.

All these cases were taken together and the Bommai case ruling of 1994 became the guiding light for constitutional courts. Here, the court said floor test was the best method to judge an elected government's majority . It said, “The SC or HC can strike down the proclamation if it is found mala fide or based on ir relevant or extraneous grounds. When called upon, the Union of India has to produce the material on the basis of which action was taken. It cannot refuse to do so, if it seeks to defend the action.“

The SC also said: “The court won't go into correctness of the material or its adequacy . Its enquiry is limited to see whether the material was relevant to the action. Even if part of the material is irrelevant, the court cannot interfere so long as there's some material relevant to the action taken.“ It struck down imposition of central rule in Karnataka and Meghalaya, but upheld it under Article 356 to dismiss UP, MP and Rajasthan governments saying a state couldn't profess any religion when secularism was the cardinal constitutional principle for governance. But lessons from reversal in constitutional courts have seldom deterred political one-upmanship. To prevent Nitish Kumar from coming to office in 2005, Central rule was imposed in Bihar. SC struck it down. Before the Uttarakhand HC decision, the Congress challenged Article 356's use to dismiss Nabam Tuki in Arunachal. SC's ruling in the case is awaited.