Pigeons: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Feeding pigeons

The consequences

Jasjeev Gandhiok & Paras Singh, Oct 14, 2019: The Times of India

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok & Paras Singh, Oct 14, 2019: The Times of India

For years untold, the common pigeon — also known as blue rock pigeon — has been seen as a symbol of love. And while feeding them at traffic islands may be some people’s way of seeking a staircase to heaven, the practice has become a major safety hazard in more ways than one.

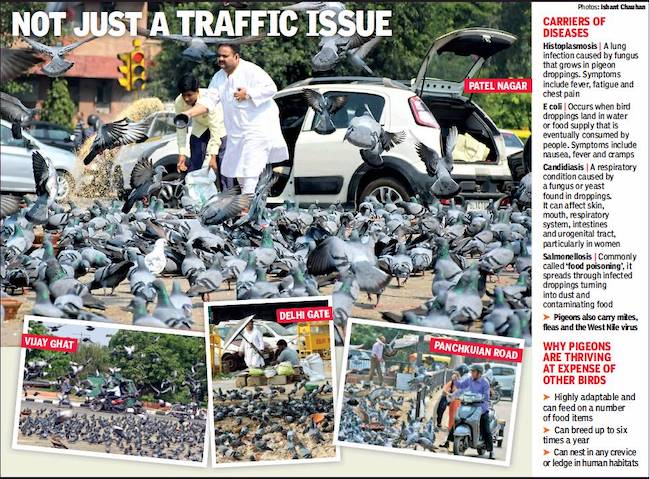

Last week, a woman was killed and her husband and daughter injured on Lajpat Nagar flyover when their scooter was hit by a BSF bus while they were overtaking a parked car whose driver had stopped there to feed pigeons. The incident illustrated how the flock of birds at these islands not only causes a nuisance, but also poses a threat to bikers who try to manoeuvre their way to avoid being hit by them. People stopping by to feed these birds, too, risk their own lives in doing so. At places where railings and fences have been installed to stop this practice, seeds are still dropped from the sides, as TOI noticed when it visited some of these popular haunts.

Birders say this practice of feeding the pigeons is not only destroying their instinct to hunt, but also creating food security to help them breed. Their proliferation is to the detriment of other species, once common such as the house sparrow and the Brahminy mynah. To add to such worries of ornithologists, health experts also say that pigeon droppings and feathers are associated with respiratory disorders. “Similar to monkeys, pigeons have become a pest and this is bad news for other birds. At places where fences have been put, people are still feeding them. Diseases can easily spread to people without them even realising it,” said birder Nikhil Devasar.

“There are a lot of foraging points across the city that are helping pigeons grow in numbers,” said Faiyaz Khudsar, scientist in charge at Yamuna Biodiversity Park. “They can feed on many types of grain and are very flexible about nesting. They also congregate in many areas, which means there is less space available for sparrows or smaller birds to nest in.”

Khudsar added that people should realise that feeding pigeons did not guarantee them a spot in heaven, but actually left them at risk of respiratory disorders. “People regularly present in areas where pigeons feed can contract diseases through their droppings and feathers,” he said. Studies have that found bird droppings and feathers can lead to diseases, such as histoplasmosis, candidiasis and cryptococcosis, which can be fatal in some cases. The birds are also carriers of ectoparasites, including bed bugs and yellow mealworms. Pigeons are considered an invasive species. They are quick breeders, hatching chicks up to six times a year.

Zoologist Surya Prakash feels “human interference” has added to the problem of proliferation. “Not only are birds very adaptable, but they also need to find food. The fact that humans are providing the pigeons food is disturbing the natural balance,” said Prakash. The increase in pigeons has seen an accompanying depletion in sparrow populations. Devasar feels the pigeons’ capacity to adapt has allowed them to nest and breed in spaces where other birds cannot. “Be it under a window AC, in crevices or on shelves, pigeons can nest anywhere,” Devasar pointed out. “Therefore, they have easily taken over spaces where once only sparrows could be found. Naturally sparrows are now rare in urban areas.”

A senior public health official from south corporation acknowledged the challenge. “The Delhi Municipal Corporation Act grants us powers to act in case a certain animal population starts causing a public health crisis. With no check on them by other predatory birds, the pigeon population is assuming gigantic proportions. They can soon be categorised as urban bird pests,” an official said. He added: “Each pigeon is estimated to create 11.5kg of excreta every year. Since this excreta is acidic in nature, it damages buildings and monuments. It also spreads salmonella germs.”

When TOI contacted the corporations on the issue, officials said specialised posts and non-lethal methods could be used to control the pigeon count. “Earlier, control of animal causing diseases used to come under the public health department, but the task was later shifted to the veterinary department. We had specialised posts like red gang coolies who would keep a tab on rodent population, but over the years, such posts have been phased out,” an official said.

Another SDMC official suggested that department use non-chemical, non-lethal techniques like netting and trapping. “But the best way is to control the rampant feeding on the roadsides. Police should not allow these feeding islands to prosper,” the official said. A senior veterinary department official asserted that pigeons were covered under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, and managing such “wild animals” and their habitat was the mandate of forest departments and not the local bodies.

Kabootarbaazi

As of 2025

ShoebKhan, Oct 26, 2025: The Times of India

Every evening, the rooftops of Khadim Mohalla in Ajmer come alive with anticipation. Children lean over parapets, while elders pull a stool closer to sit and cradle their glasses of evening tea, waiting for the moment when a sharp whistle slices through the descending twilight.

In a heartbeat, hundreds of pigeons burst into the pale sky. Their silver-grey-black wings beat like a living storm. These are no ordinary birds but the prized performers of ‘kabootarbaazi’, a centuries-old sport where ustads (experts) guide flocks through coded signals — bamboo taps, soft whistles, quick claps — creating sky patterns only the birds understand.

The flock first circles low, then stretches into a perfect V, U and S. Below, spotters spread across the terraces track their kilometre-long sweep, eyes fixed on the moving cloud and wary of ‘ chidimaars ’ — eagles and vultures that prey on the pigeons.

Mughal Legacy With Modern Wings

Kabootarbaazi was first chronicled in Babur’s memoir, Tuzuk-e-Baburi, as a royal pastime. From the Mughal courts, it travelled along caravan routes of faith and trade, finding a home around Sufi shrines and Muslim centres.

Today, it primarily thrives in Ajmer, Tonk and Jaipur’s old quarters — especially the sprawling Labbaik House terrace in Silawat Mohalla of Ajmer, set against the Dargah’s minarets. Here, tradition meets technology — pigeon lofts now have CCTV cameras, and dramatic flights are streamed live on Instagram, drawing fresh audiences.

At the heart of it all stands 32-year-old Syed Sohail Chishty, alias Golu Ustad, a hereditary priest at the Ajmer Dargah and an ustad of rare skill. With many khalifas (masters) and shagirds (apprentices) under him, he is preparing for a 2,021-pigeon mega race this winter — “the biggest of my life,” he says.

Sohail’s 2,500 birds collected over a decade have already cost him Rs 25 lakh in total. Some came at Rs 10,000 each while Rs 25,000-35,000 is spent every month on training and feed. The prized breeds — Kalapankhi, Lakka, Pari and Mookhee — are sleek, precise and bred for endurance. They can live for 15-20 years, fly for as long as 10 hours without a break and are known for memorising their ustad’s terrace signals and voice.

They carry the legacy of a sport once celebrated in royal courts, now kept alive more by passion than patronage. These high-flying athletes live like royalty. Their daily menu is a tonic of almonds and raisins ( badam munakka ), coriander seeds, mirchi charu , melon seeds ( magaz ), akal khera and mulethi , all mixed with bajra to build strength and stamina for flights that can last the entire day.

Rules Of The Sky

Two rival teams — Sohail’s and a club of 20 pigeon fanciers — have signed a stamp-paper agreement. Pigeons will be released from two terraces and allowed to mingle in the open sky. Each side uses only familiar calls and permitted symbols like bamboo sticks to lure the opponent’s birds. Victory belongs to whoever attracts the most rivals to their terrace by day’s end.

“I’m giving everything to this competition,” Sohail says. “My entire flock will bear a yellow mark on the neck and a seal on their wings. They will be released on Jan 10, between 1pm and 2pm, along with the competing party from the terrace close by. Trained to circle the rival flocks, they (pigeons) will try to lure/force the opponent’s birds down to my terrace.” The prize is not cash, but a winner’s shield and a community feast in the victor’s honour. Under Mughal tradition, the victorious ustad even claimed the defeated team’s khalifas and shagirds.

But competition isn’t the only risk — the chidimaars hover above, ready to snatch pigeons mid-flight, adding a wild, unpredictable twist to the spectacle.

Even though the race is four months away, Sohail’s day begins at dawn, training 200-300 pigeons in batches, fine-tuning their flying height, call recognition, and diet. “This is the last generation for kabootarbaazi,” Sohail laments. He calls himself the last ustad from his Ahle-Khandan (extended family), citing rising costs and waning interest.

Yet, despite challenges, rivalries still ignite the skies of Ajmer, Tonk, and Jaipur — keeping alive a Mughal sport that once thrilled emperors and is now finding new wings on Instagram. Tonk’s Sky Kings

About 160km from Ajmer, in Tonk — the old city of the nawabs — municipal councillor and master kabootarbaaz Yaseen Khan is busy sending out invitations to fanciers from Makrana, Ajmer, Bhilwara and Jaipur.

Yaseen lives in a palatial haveli in Gulzar Bagh, its wide terrace surrounded by tightly packed houses where residents gather every evening to watch his pigeons take flight. Together with his brother Mohsin, he keeps nearly 4,000 pigeons — among the largest private flocks in India — sourced from Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan and Gujarat. A fourth-generation kabootarbaaz, he spends Rs 20,000-Rs 30,000 a month on their care, most of it on a special, energy-rich diet.

Unlike Sohail’s dramatic capture matches, Yaseen specialises in “strength contests”. Here, birds from rival teams are released together, and the winner is the one that circles the sky the longest within sight of the terrace — often 10 hours or more.

“This is a pure test of stamina,” Yaseen says. “Like Formula 1 drivers who shed weight after a race, our pigeons also lose weight after these lengthy flights. The moment they land, we give them quick therapy and two full days of rest.”

Breathing New Life

Although rising costs and dwindling public interest worry him, Yaseen believes social media is breathing new life into the sport. “Instagram and live streaming have given kabootarbaazi a second life,” he says. “People who had never heard of it are now watching our races in real time. This new audience has brought recognition and a wave of young followers eager to learn the art.” Both Yaseen and Sohail now run dedicated Instagram accounts, posting race highlights and issuing friendly challenges to attract new fans and keep this centuries-old tradition alive. Local historian Syed Sadiq Ali recalls that the nawabs introduced kabootarbaazi in the 17th century, gifting prized birds to royal houses in Jhalawar, Kota, Jaipur and Karauli. “When cricket first arrived,” Ali says, “people even compared it to kabootarbaazi — both are day-long spectacles.”

Lost Patronage

About 100km from Tonk, in Jaipur, pigeon races once drew the same excitement as kite-flying. Inside the narrow lanes of Babu Ka Tibba in Ramganj, within the Walled City, Suleman Khan, now in his mid-40s, watches what he calls the sport’s last days. “Five years ago, I had nearly 200 birds. Last year it came down to 100, and now my tally is barely 50 pigeons,” he says. Unlike Sohail or Yaseen, Suleman does not compete in races because his birds lack the required strength. But he still flies them every evening for the love of tradition. “People now dismiss it as faltu logon ka kaam (idlers’ occupation),” Khan says, adding that in his childhood, families and friends would call him and other ustads with pride. “Now they only make fun of us.”

Fight For Survival

The numbers have dwindled for many reasons: the soaring cost of feed and medicines, a lack of young enthusiasts, and the falling social prestige that once crowned every ustad. Modern entertainment and changing lifestyles have pulled people away, leaving the sport to a handful of loyalists.

Rashmi Jain, the head of the sociology department of Rajasthan University, says the decline reflects a larger cultural shift. “Every tradition needs patronage,” she says. “Neither the royals nor the govt supports it anymore. Historically, it was a sport of the nobles. Common people were spectators only — that exclusivity is one reason new entrants have stopped,” Jain adds. For today’s bird fanciers, the slight motivation that remains often comes from their social media audiences, whose likes and comments help sustain their passion even when families question the time and expense.

Pigeon races

Kolkata, 2025

Sudipto Das, March 3, 2025: The Times of India

Kolkata : Kolkata was once the feather in the pigeon-racing cap, with several city clubs vying for coveted trophies. However, only a couple of them remains, and a handful of pigeon fanciers continue with their passion. The city has also relinquished the honour of being the capital of the racer Homer breed in India to Chennai.

The number of serious racing pigeon fanciers in Kolkata has dwindled to less than 50 from around 500 in the 80s. From the early 50s until the mid-90s, Chinese-origin residents of Kolkata dominated pigeon-racing contests in India. Still active, Calcutta Racing Pigeon Club (CRPC) — the oldest such club in India — was founded by PS Lee, a Chinese, in 1953. CRPC’s current president, YS Chen, is also of Chinese origin.

During peak racing times, a Homer pigeon would travel to its city’s loft after completing a race within a day from Allahabad to Kolkata (814km), faster than any express train. It is still a mystery how these pigeons found their way home over such long distances. Studies say the compass mechanism of a homing pigeon likely relies upon the Sun. Some researchers believe it uses magnetoreception, which involves relying on Earth’s magnetic fields for guidance. In 1993, KK Lee’s bird “Mischievous” returned from Allahabad to Kolkata in a record time of just 9 hours 30 minutes. It started at 7am and reached Kolkata the same day by 4:30pm. In 1983, YS Chen’s pigeon “Snow Ball” became Delhi champion with a record timing of 23 hours 37 min from Delhi to Kolkata. In 1988, William Ku’s “Foreign Currency” shattered the record and finished the race in just 18 hours 17 minutes. The average speed of a Homer pigeon is 60-80 kmph. Debjit Mullick, a third-generation pigeon fancier and a CRPC member, still has more than 120 Homer pigeons at his century-old house’s rooftop. “The cost of a certain bloodline of a Homer pigeon can go up to a lakh. Due to my job, I have been unable to participate in long-distance racing over the last few years,” Mullick said. Others pointed to various factors that have clipped pigeon-racing’s wings. “The city highrises and ever-increasing costs of upkeeping a Homer pigeon, followed by impediments of rail booking for transporting pigeons and recent stringent law on aviculture, are taking a toll on the century-old hobby,” said Pratip Nandy, president of Calcutta Racing Pigeon Organisation (CRPO. The member strength of CRPO has shrunk to 7 from 50 and CRPC’s to 28.

Sanjoy Das, organising secretary of CRPC, explained training schedules. “The training for young pigeons usually starts in late Nov by short-distance releases of birds from Dankuni (on the city’s fringes) to Kolkata, followed by Galsi and Tarakeshwar,” said Das. Long-distance individual races start usually from mid-Dec until scorching summer sets in. The races are usually conducted with both young and old birds from Kolkata to Asansol (200km), Hazaribag (333km), Gaya (458km), Mughalsarai (661km) and finally Allahabad. “Our birds are trained in such a way that during daytime long-distance flying, they hardly halt, except for rare water breaks,” said Shyamal Das, secretary of CRPO.

Such clubs stopped extreme long-distance races (1,000 km and above) like Kolkata to Kanpur (1107 km) and finally Delhi (1441 km) for old birds because these pigeons need an overnight halt after sundown. “The pigeons are unable to navigate in the dark and often fall prey to owls at night, which leads to many injuries and the missing of the highly expensive Homer pigeon,” said Ashim Mondal, another fancier. It is likely the British first brought this special breed of domestic pigeon to Calcutta for its unique ability to find its way home over extremely long distances. It used to carry messages and was referred to as a “pigeon post”, and the particular breed was used during wars.

Nurtured by zamindar families during World War II, the British Army seized all the homing pigeons for their use. This resulted in the discontinuation of the racing events. Abani Das, a descendant of Rani Rashmoni, managed to hide some he had imported from England. Later, P SLee, the Chinese shoe businessman, bought four such pigeons from Das and established CRPC at Bentinck Street.