Santal Parganas

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Santal Parganas

Southern District of the Bhagalpur Division, Bengal, lying between 23 48' and 25 18' N. and 86 28' and 87 57' E., with an area of 5,470 square miles. It is bounded on the north by the Districts of Bhagalpur and Purnea; on the east by Malda, Murshid- 1 V. A. Smith, in \ht Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1898, p. 508, note. abad, and Birbhum ; on the south by Burdwan and Manbhum ; and on the west by Hazaribagh, Monghyr, and Bhagalpur.

Physical aspects

The general aspect of the District is undulating or hilly; to the north-east, however, it abuts on the Gangetic plain, and a narrow strip of alluvial land about 650 square miles in area thus falls within it. The RAJMAHAL HILLS, which cover 1,366 square miles, here rise steeply from the plain, but are nowhere higher than 2,000 feet above the level of the sea, their average elevation being considerably less. Among the highest ridges are Mori and Sendgarsa. The major portion of these hills falls within the Daman-i-koh Government estate, which has an- area of 1,351 square miles. Among the highest ridges outside the Daman-i-koh are the Num, Sankara, Ramgarh, Kulanga, Sarbar, Sundardihi, Laksh- manpur, and Sapchala hills. East and south of these hilly tracts the country falls away in undulations, broken by isolated hills and ridges of gneiss of sharp and fantastic outline. The Ganges forms the northern and part of the eastern boundary, and all the rivers of the District eventually flow either into it or into the Bhaglrathi. The chief of these are the Gumani, the Maral, the Bansloi, the Brahman!, the Mor or Morakhi with its tributary the Naubil, the Ajay, and the Bara- kar.

None of them is navigable throughout the year. Archaean gneiss and Gondwana rocks constitute the greater portion of the Santal Parganas, the latter represented principally by the vol- canic rocks of the Rajmahal Hills, which occupy an elevated stiip of land along the eastern border, while to the west the undulating area that constitutes the greater part of the District consists of Bengal gneiss, which is remarkable for the great variety of crystalline rocks which it contains. The Gondwana division consists of the Talcher, Damodar, Dubrajpur, and Rajmahal groups. The Talcher and Damo- dar belong to the Lower Gondwanas, and the other two groups to the Upper. The volcanic rocks of the Rajmahal group are the predomi- nant member of the series, and they constitute the greatest portion of the hills of that name. They are basic lavas resembling those of the Deccan trap, and vary in their coarser types from a dolerite to a compact basalt in the finer-grained varieties. A trachytic intrusion situated in the Hura coal-field, about 22 miles south-east of Colgong, although petrologically quite different from the basic basalts and dole- rites, may nevertheless belong to the same volcanic series. Sedimen- tary beds, consisting principally of hard white shales, sometimes also of hard quartzose grits or carbonaceous black shales, occur frequently intercalated between successive flows ; and these are of great interest on account of the beautifully preserved fossil plants which they contain.

They are mostly cycadaceous plants together with some ferns and conifers, and are identical with those found in the Upper Gondwana at Jubbulpore, in Cutch and various other places, and have been of great assistance to geologists in determining the age of the series. In the Rajmahal Hills, the Gondwana groups underlying the volcanic group are found principally along the western border of the range. The outcrops are very discontinuous, owing partly to the faulted nature of the western boundary, and partly to the overlaps between the different members, which in the case of the Barakars, Dubrajpur, and Rajmahal amount to a well-marked unconformity. The Talchers are very poorly represented. They consist of the usual greenish silts and sandstones, with only a local development of the well-known boulder bed. These rocks are supposed to be of glacial origin.

The next group is the most important from an economic point of view, as it contains the coal-measures. Along the western border of the hills, it constitutes several coal-fields, which, enumerated from north to south, are: the Hura coal-field, a tract about 15 miles long from north to south, commencing about 13 miles south-east of Colgong; the Chu- parbhita coal-field, about 10 miles farther south in the valley of the Gumani ; the Pachwara field, in the Bansloi valley ; and the Brahman! coal-field, in the valley of the river from which it is named. In the three southern fields the Damodar rocks are lithologically similar to the Barakar beds of the Ramganj coal-field, consisting of alternations of grit, sandstone, and shale, with occasional beds of inferior coal. The coal-measures of the Hura field are lithologically different ; they consist of friable felspathic grits and soft white shales, with a few thick seams of inferior coal, and correspond possibly with the Ram- ganj group of the Damodar coal-fields. The Dubrajpur group, which either intervenes between the Damodar and volcanic rocks or rests directly on the gneiss, to be overlapped in its turn by the volcanic rocks themselves, consists of coarse grits and conglomerates, often ferruginous, containing quartz and gneiss pebbles, with occasionally hard and dark ferruginous bands.

The south-western portion of the District contains the small Deogarh coal-fields and the northern edge of the Ranlganj coal-field. The Talcher and Barakar are the groups represented. The boundaries of these coal-fields are often faulted. There are numerous dikes and intrusive masses of mica peridotite and augite dolerite, the underground representatives of the Rajmahal flows. These intrusions occur in pro- fusion in the surrounding gneiss. The coal in the Deogarh fields is neither plentiful nor of good quality. In the north of the District the rocks disappear beneath the Gangetic alluvium 1 .

The narrower valleys are often terraced for rice cultivation, and the

1 Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vols. vii and xiii, pt. ii, and Records t Geological Survey of India, vol. xxvii, pt ii. The above account was contributed by Mr. E. Vredenburg, Deputy-Superintendent, Geological Survey of India* rice-fields and their margins abound in marsh and water plants, The surface of the plateau land between the valleys, where level, is often bare and rocky, but where undulating, is usually clothed with a dense scrub jungle, in which Dendrocalamus strictus is prominent. Through- out the District the principal tree is the sal (Shorea robusta)^ but all trees characteristic of rough and rocky soil are found in the jungles. Such are the palds (Bittea frondosd), tun ( Cedrela Toond)^ asan ( Ter- minalia tomentosa)^ baherd (Terminalia Chebuld), haritakl (Terminalia belerica), arjnn (Terminalia Arjund], Phyllanthus EmbUca^ jdmun (Eugenia Jambolana), babul (Acacia arabica), khair (Acacia Catechu}, mahitd (Bassia latifolia\ bakul (Mimusops Elengi\ Mallotus philip- pinensis, kdntdl (Artocarpus vttegrifolta), Artocarpus Lakoocha, Lager- stroemia parviflora, Anogeissus latifolia, gamkdr (Gmelina arborea\ kusum (Schleichera trtjuga), and dbnus (Diospyros melanoxyloti),

Outside the Government estates, where forest is protected, the jungle is being gradually destroyed and big game has almost disappeared. The last elephant was shot in 1893; a ^ ew bears, leopards, hyenas, and spotted deer survive, but the Santal is as destructive of game as of jungle. Wild duck, snipe, and quail abound in the alluvial tract. Partridges are also fairly common, and partridge taming is a favourite amusement of the Santals. Peafowl and jungle-fowl are still to be found in the Dcaman-i-koh and in the hills to the south and east of Dumka.

The alluvial strip of country above alluded to has the damp heat and moist soil characteristic of Bengal, while the undulating and hilly portions of the District are swept by the hot westerly winds of Bihar, and resemble in their rapid drainage and dry subsoil the lower plateau of Chota Nagpur. In this undulating country the winter months are very cool and the rains not oppressive, but the heat from the end of March to the middle of June is great. Mean temperature rises from 64 in December and January to 88 in April and May. The mean maximum is highest (100) in April; but after May it drops rapidly, chiefly owing to the fall in night temperature, and from July to October remains almost constant at 88 and 89. The mean minimum is lowest (51) in December and January. The annual rainfall averages 52 inches, of which 8-8 inches fall in June, 13-2 in July, 11-4 in August, and 9-2 in September.

Owing to the completeness of the natural drainage and the custom of accumulating excess rain-water by dams, floods seldom cause much damage. The only destructive flood within recent years occurred on the night of September 23, 1899, in the north-west of the Godda sub- division. The storm began in the afternoon, and by 8 a.m. next morning io- 1 inches of rain had been registered at Godda. The natural water- courses were insufficient to carry away the water, and a disastrous inundation ensued. It was estimated that 88 1 lives were lost, while

upwards of 6,000 cattle perished and 12,000 houses were destroyed. The villages in the submerged area were afterwards visited by a some- what severe epidemic of cholera, probably due to the contamination of the water-supply.

History

Until the formation of the District in 1855, the northern half formed part of Bhagalpur, while the southern and western portions belonged to Blrbhum. The Rajmahal Hills lay within Bhagal- is ory. p ur c j oge to t ^ e ii ne O f communication between Bengal and Bihar, and the Paharias ('hilhnen') who inhabited them lived by outlawry and soon forced themselves on the attention of the East India Company. The Muhammadan rulers had attempted to confine the Paharias within a ring fence by granting zamlndaris and jdglrs for the maintenance of a local police to repel incursions into the plains j but little control was exercised, and in the political unrest of the middle of the eighteenth century these defensive arrangements broke down. Repressive measures were at first attempted with little effect, but between 1779 and 1784 Augustus Clevland succeeded by gentler means in winning the confidence of the Paharias and reducing them to order. He allotted stipends to the tribal headmen, established a corps of hill-rangers recruited among the Paharias, and founded special tribunals presided over by tribal chiefs his rules were eventually incorporated in Regulation I of 1796. To pacify the country, Govern- ment had to take practical possession of the Paharia hills to the ex- clusion of the zammddrs who had previously been their nominal owners.

The tract was therefore not dealt with at the Permanent Settlement ; and finally m 1823 Government asserted its rights over the hills and the fringe of uncultivated country, the Darnan-i-koh or 'skirts of the hills,' lying at their feet. An officer was appointed to demarcate the limits of the Government possessions, and the rights of the jagirdars over the central valley of Manjhua were finally resumed in 1837. A Superintendent of the Daman was appointed in 1835; an d he encouraged the Santals, who had begun to enter the country about 1820, to clear the jungle and bring the valleys under cultivation. The Paharias, pacified and in receipt of stipends from Government, clung to the tops and slopes of the hills, where they practised shifting culti- vation. The valleys offered a virgin jungle to the axes of the Santals who swarmed in from Hazaribagh and Manbhurn. On the heels of the Santals came the Bihari and the Bengali mahdjans (money-lenders).

The Santal was simple and improvident, the mahdjan extortionate. The Santals found the lands which they had recently reclaimed passing into the hands of others owing to the action of law courts; and in 1855, starting with the desire to revenge themselves on the Hindu money-lenders, they found themselves arrayed in arms against the British Government. The insurrection was not repressed without bloodshed, but on its conclusion a careful inquiry was held into the grievances of the Santals and a new form of administration was intro- duced. Regulation XXXVII of 1855 removed the area of the present District from the operation of the general Regulations and placed the administration in the hands of special officers under the control of the Lieutenant-Governor.

The jurisdiction of the ordinary courts was suspended, and the regular police were removed. Five districts (col- lectively named the Santal Parganas) were formed and placed under the control of a Deputy and four Assistant Commissioners, each of whom had a sub-assistant and was posted with his sub-assistant at a central point of his district. These ten officers were intended simply for the purpose of doing justice to the common people, and tried civil and criminal cases and did police work \ revenue work and the trial of civil suits valued above Rs. 1,000 were carried on by the District staff of Birbhum and Bhagalpur.

Under this system the Deputy-Commissioner lived at Bhagalpur, and of the officers left in the districts, three were on the loop and three on the chord line of rail, while only two were posted in the important districts of Dumka and Godda, which contained nearly half the population of the Parganas. In course of time, however, the Santal Parganas were more or less brought under the ordinary law and procedure of the ' regulation ' Districts, and the Deputy-Commissioner was practically transformed into a Judge, Accordingly, when in 1872 an agitation again began among the Santals, directed chiefly against the oppression of the zaminddrs^ and attended by acts of violence, it was felt that this tract required a simpler form of administration than other parts of Bengal, and a special Regulation (III of 1872) was passed for the peace and good government of the Santal Parganas. Under its provisions, a revenue ' non-regulation 7 District was formed ; the Deputy-Commissioner was appointed to be the District officer, with head-quarters at Dumka instead of Bhagalpur, and the three tracts of Deogarh, Rajmahal, and Godda were reduced to the status of subdivisions. The areas now composing the subdivisions of Pakaur and Jamtara were at the same time attached as outposts to Dumka, and that part of the police district of Deogarh which is included in the Jamtara subdivision and in the Tasaria and Gumro taluks was withdrawn from the jurisdiction of the regular police and included in the non-police area. These changes completed the autonomy of the District.

Population

Population increased from 1,259,185 in 1872 to 1,567,966 in 1881, to 1,753,775 in 1891, and to 1,809,737 in 1901 : the increases in 1881 and 1891 were largely due to greater accuracy in Poptl i at i olj enumeration. The District is on the whole healthy, but malarial fever prevails in the low-lying country bordering on the Ganges, and also in parts of the hills.

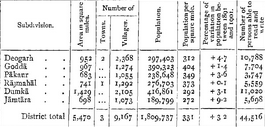

The principal statistics of the Census of 1901 are shown below:

The three towns are MADHUPUR, DEOGARH, and SABIBGANJ; DUMKA, the District head-quarters, was constituted a municipality in 1903. The population is most dense in the low and level country on the north-east and north-west; the Daman-i-koh in the centre of the District is a typical part of Chota Nagpur and is sparsely inhabited, and the popu- lation is stationary or decadent, except in the Rajmahal subdivision, where the collection of sabai grass (Ischoemum angustifoliimi) for the paper-mills gives profitable employment. Elsewhere emigration has been busily at work, especially among the Santals, who chafe under the restrictions imposed by the Forest department on the indiscriminate felling of timber. Outside the Daman-i-koh the only tracts that show a decline are Rajmahal, Sahibganj, and Poreya.

In the tract first mentioned the decrease is due to migration across the Ganges, while in Sahibganj it is attributed to an outbreak of plague at the time of the Census. Poreya is a poor and barren tract and, like the Daman-i-koh, has lost by emigration. The smallness of the net increase for the whole District during the decade ending 1901 is due to the large scale on which emigration is taking place. It is, in fact, estimated that about 182,000 persons must have left the District during that period, and that the natural increase of the population was at least 10 per cent. The most striking features of the migration are: firstly, its great volume ; and secondly, the strong tendency of the people to move eastwards.

There is a large influx from all the adjoining Districts west of a line drawn approximately north and south through the centre of the District, i.e. from Bhagalpur, Monghyr, Hazaribagh, and Man- bhum ; but the movement is still stronger in the direction of the Dis- tricts east of this line, i. e. Purnea, Malda, Murshidabad, Birbhum, and Burdwan. The immigrants from the west exceed 83,000, while the emigrants to the east number close on 117,000. The great migration of the Santals to this District from the south and west took place during the middle part of the nineteenth century, and many of the immigrants enumerated in the last Census are probably the survivors of those who took part in the movement.

The tribe is still spreading east and north and the full effect of the movement is not exhausted in the Districts that adjoin the Santal Parganas, but makes itself felt even farther away in those parts of Dinajpur, Rajshahi, and Bogra which share with Malda the elevated tract of quasi-laterite known as the Barind. Of emigration to more distant places the most noticeable feature is the exodus to the Assam tea gardens, where more than 31,000 natives of this District were enumerated in 1901, and to Jalpaigurl, where they numbered more than 10,000. A large variety of dialects are used in the District Bengali, spoken by 13-5 per cent, of the population, includes the Rarhi &?//, or classical Western Bengali, and Malpaharia or the broken Bengali spoken by converted aborigines in the centre of the District. Biharl is spoken by 46 per cent. ; the main dialect is Mai thill, which includes a sub-dialect known as Chhika Chikki bolt, but a dialect of Magadhi, which has been affected by its contact with Bengali, is also largely used ; this is called by Dr. Grierson Eastern Magadhi, and is locally known as Karmall or Khotta or even as Khotta Bangala. Santall itself, which is spoken by 649,000 persons, is a dialect of the Munda family, while Malto belongs to the Dravidian group. Hindus constitute 56-1 per cent, of the total population, Animists 34-9 per cent., and Muhammadans 8-4 per cent.

The Santals are now the distinctive caste of the District, and in 1901 numbered 663,000, of whom 74,000 were returned as Hindus and 589,000 as Animists. They are a typical race of aboriginal stock, and are akin to the Bhumijs, Hos, and Mundas. Their complexion varies from very dark brown to an almost charcoal black, and their features are negritic. The original habitat of the race is not known, but there is no doubt that from a comparatively remote period they have been settled on the Hazaribagh table-land ; and it is noticeable that the Damodar river, by which its southern face is drained, is the terrestrial object most venerated by them. Within the last few cen- turies they have worked eastwards, and are numerous in the eastern half of the Chota Nagpur plateau and in Midnapore ; and, as has been already related, they are now emigrating to North Bengal and Assam. They worship various deities, of which the chief is the Marang Buru^ who is credited with far-reaching power, in virtue of which he associates both with the gods and with demons. Each Santal family has also two special gods of its own, the Orak bonga or household god and the Abjebonga or secret god. Their principal festival is the Sohrai or harvest festival, celebrated after the chief rice crop of the year has been reaped. Public sacrifices of fowls are offered by the priest in the sacred grove; pigs, goats, and fowls are sacrificed by private families, and a general saturnalia of drunkenness and sexual licence prevails. Chastity is in abeyance for the time, and all unmarried persons may indulge in promiscuous intercourse. Next in importance is the Bahapuja, held in Phalgun (February-March) when the sal tree comes into flower, Tribal and family sacrifices are held, many victims are slain and eaten by the worshippers, every one entertains his friends, and dancing goes on day and night.

The communal organization of the Santals is singularly complete. The whole number of villages comprising a local settlement of the tribe is divided into certain large groups, each under the superin- tendence of a parganait or circle headman. This official is the head of the social system of the inhabitants of his circle ; his permission has to be obtained for every marriage, and, in consultation with a panchdyat of village headmen, he expels or fines persons who infringe the tribal standard of propriety. He is remunerated by a commission on the fines levied, and by a tribute in kind of one leg of the goat or animal cooked at the dinner which the culprits are obliged to give. Each village has, or is supposed to have, an establishment of officials holding rent-free land. The chief of these is the man/hi or headman, who is usually also ijaradar where the village is held on lease under a zamindar; he collects rents, and allots land among the ryots, being paid for this by the proceeds of the man land which he holds free of rent. He receives R. i at each wedding, giving in return a full bowl of rice-beer. The pramanik, or assistant headman, also holds some man land. The jog-manjhi and the jog-pramanik are executive officers of the manjhi and the pramanik, who, as the Santals describe it, 'sit and give orders' which the jog-manjhi and jog-prdmdnik carry out. The naiki is the village priest of the aboriginal deities, and the kudam naiki is the assistant priest, whose peculiar function it is to propitiate the spirits (bhuts) of the hills and jungles by scratching his arms till they bleed, mixing the blood with rice, and placing it in spots frequented by the bhuts. The gorait or village messenger holds man land and acts as peon to the headman, and is also to some extent a servant of the zamindar- His chief duty within the village is to bring to the manjhi 2^ pramanik any ryot they want. Girls are married as adults mostly to men of their own choice. Sexual intercourse before marriage is tacitly recognized, it being understood that if the girl becomes pregnant the young man is bound to marry her. Should he attempt to evade this obligation, he is severely beaten by the jog-manjhi^ and, in addition to this, his father is required to pay a heavy fine.

Other castes are Bhuiyas (119,000), identified by Mr. Oldham with the Mais, whom in many respects they closely resemble ; Musahars (28,000), whom Mr. Risley considers to be akin to the Bhuiyas ; Male Sauria Paharias (47,000) and Mai Paharias (26,000), two Dravidian tribes of the Rajmahal Hills, the former of whom are closely akin to the Oraons. The Muhammadans are chiefly Shaikhs (77,000) and Jolahas (63,000). Agriculture supports 8r per cent, of the population, industries 7 per cent., commerce 0-6 per cent., and the professions 0-8 per cent.

Christians number 9,875, of whom 9,463 are natives, including 7,064 Santals. The largest numbers are to be found in the head-quarters subdivision, where the Scandinavian Lutheran Mission, called the Indian Home Mission, has been at work for over forty years and maintains 29 mission stations and 9 schools; it has also a colony in Assam, where it owns a tea garden. The Church Missionary Society, which works in the Godda and Rajmahal subdivisions, has similarly established an emigrating colony for its converts in the Western Duars. Several Baptist missionaries work in the Jamtara subdivision, one of whom has established two branches of his mission in the head-quarters subdivision. Other missions are the Christian Women's Board of Missions and the Methodist Episcopalian Mission, the latter of which works chiefly among Hindus and Muhammadans } it maintains a boarding-school, with an industrial branch in which boys and girls are taught poultry-keeping, gardening, fruit-farming, and carpentry.

Agriculture

The soil varies with the nature of the surrounding hills : where basalt or felspar or red gneiss prevails, the soil is rich ; but where the hills are of grey gneiss or of granite in which a .quartz prevails, it is comparatively barren. The pro- ductiveness of the land is mainly dependent on its situation and its capability of retaining moisture. Where the surface is level and capable of retaining water coming from a higher elevation, it is not affected even by shortness or early cessation of rainfall, and good crops of rice are obtained. If, however, the slope is too steep, the rush of water often brings with it drifts of sand, which spoil the fields for rice cultivation and damage the growing crops. In the alluvial tract the system of cultivation differs in no way from that in vogue throughout the plains of Bihar. On the hill-sides level terraces are cut for rice cultivation, and these are flooded as soon as possible after the rains set in, small banks being left round the edge of each plot to hold in the water. Shifting cultivation is now restricted to the Saurias of the hills in the Rajmahal and Godda subdivisions, and to certain defined areas in Pakaur. Land under cultivation is divided into two main classes, ban or high land forming about 53 per cent, of the cultivated area, and jamin or rice-fields the rest. The former, being uneven and wanting in organic matter, is ordinarily ill-suited for cultivation ; but in the immediate vicinity of villages, where the surface is fairly level and rich in organic matter, ban land produces valuable crops such as maize, mustard, the larger variety of cotton (barkapas), tobacco, castor, and Irinjdh and other vegetables.

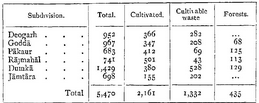

The chief agricultural statistics for 1903-4 are shown below, areas being in square miles :

Rice, which covers 1,213 square miles, forms the staple food-grain, winter rice being the principal crop. It is largely grown in the alluvial strip along the eastern boundary and the lower slopes of the ridges ; the undulating parts of the District, as well as the swampy ground between these ridges, are also sown with rice. Among the other crops are maize (262 square miles), various pulses (437 square miles), oil- seeds (360 square miles), millets, wheat and barley, sugar-cane, and cotton. Indigo was grown till recently on a small scale, but its cultiva- tion is now extinct.

Settlement figures show that within twenty years cultivation has extended by about 30 per cent, in the Daman-i-koh and by about 60 per cent, in the rest of the District, There is much waste land still available for cultivation, and rents are light. For several years past efforts have been made to stimulate the improvement of means of irrigation by loans under the Land Improvement Loans Act, and in 1901-2 Rs. 12,000 was thus advanced. Rs. 15,000 was also advanced under the Agriculturists' Loans Act at the close of the famine of 1896-7, and Rs. 6,000 in consequence of the disastrous floods of 1899-1900.

There is scarcity of fodder in the dry months, and the cattle are generally poor; animals of a better quality are, however, found in the Godda subdivision, and good milking cattle are imported from Bhagalpur. Pigs are largely kept for food by Santals, Paharias,'and low-caste Hindus.

Besides the methods of supplying water to the rice crop which have been already described, the system of irrigation as practised in the Godda subdivision consists in the construction of water channels leading from reservoirs made by throwing embankments across streams. These channels frequently pass through several villages, each village assisting in their construction and sharing in the benefits derived from a network of distributaries. There is but little irrigation from wells ; kackchd wells are sometimes dug for only one season to irrigate the sugar-cane crop from February to May, and tobacco is also grown in small patches by the aid of well-water.

Forests

At the beginning of the nineteenth century the District was mostly covered with jungle. About 1820 the Santals began to flock into it and betook themselves to the congenial occupation of jungle clearing ; while the construction of the loop res S '

railway in 1854 and of the chord-line in 1866 hastened the process. In 1875 Government instituted inquiries with a view to bringing under scientific management the Government forests in the Darnan-i-koh, and in 1876 an area of 35 square miles was set aside for special reservation. This area was formally constituted a 'reserved 3 forest, and the forest lands in the southern half of the Darnan-i-koh were constituted ' open ' forests, the management being left in the hands of the Deputy-Com- missioner. In 1894 all Government land which had not been settled with cultivators was constituted 'protected' forests under the Indian Forest Act (VII of 1878), and in 1895 the forests were placed in charge of the Forest department. The departmental system of management was, however, found not to be sufficiently elastic; and in December, 1900, the forests in the Rajmahal subdivision and part of those in the Godda subdivision were restored to the control of the Deputy- Commissioner. The hills in this tract are inhabited by Male Sauria Paharias, who are allowed the right of shifting cultivation, which renders scientific forestry impossible.

The chief tree is the sal (Shorea robustd], and its distribution is general throughout the District, except where the forest has been destroyed, as is largely the case in the north of the Daman-i-koh, by shifting cultivation and the cultivation of sabai grass. In the plains and valleys the forest is usually of pure sdl t the other principal trees being piar (Buchanania latifolia\ Semecarpus anacardium^ and dsan (Terminalia tomentosa}. On the lower slopes of the hills other species appear in considerable variety; among these are Zizyphus xylopyra^ Anogeissus latifolia, Diospyros> Stereospermum, and Bauhinia. As the hills are ascended, different species are met with, such as bamboos (Dendrocalamus strictus\ bljdsal (Pterocarpics Marsupium\ sitsdl (Dal- bergia latifolia\ gamhdr (Gmelina arbor ed) ^ Kydia calydna^ and Grewia Httaefolia^ the proportion of sal gradually getting less, till on the upper plateau it almost disappears, and on the old cleared lands gives place to a dense growth of shrubby trees, chief among which are Nyctanthes Arbor-tristiS) Wendlandia^ Gardenia^ Flacourtia^ Woodfordia^ and Ano- geissus. At present most of the sal trees are mere shoots from stumps 2 to 3 feet high, which, when they grow to a large size, are always unsound at the base. Cultivating tenants of Government are allowed to remove free of charge all timber of the unreserved species and such minor products as are required for their domestic consumption.

The area under the Forest department is 292 square miles; and in 1903-4 the revenue under its control was Rs. 42,000. Besides this, 143 square miles are managed by the Deputy-Commissioner. The chief sources of revenue are timber, bamboos, and sdbai grass, while minor items are fuel, coal, stone, and tasar silk cocoons. Other jungle products are lac, found on the palas (Butea frondosa), ber (Zizyphus Jujubd), and plpal (Ficus religiosa) trees ; beeswax, catechu, honey, konjtu Kb&jombar (two creepers used for making rope), and also a variety of edible products. The use of jungle products as a means of subsistence is confined for the most part to Paharias, Santals, and Bhuiyas.

Minerals

Stone is quarried on the hills bordering the loop-line of the East Indian Railway from Murarai to Sahibganj ; the stone quarried is for the most part supplied as ballast to the railway, the Calcutta municipality, and certain District boards. In 1903 coal-mines were worked at Bhalkl, Domanpur, Ghatchora, and Sarsabad in the Dumka subdivision, and at Sultanpur and Palasthol mines in the Jamtara subdivision. The average daily number of persons employed was 79, and the output of coal was 2,361 tons. The Jamtara mines, which lie in the Damodar coal-field, produce good coal, but are only worked on a small scale for want of access to the railway ; elsewhere the coal is limited in extent and inferior in quality, and is generally fit only for brick-burning. Hand labour is employed as a rule in digging out the coal, the wages paid being Rs. 1-4 to Rs. 1-8 per 100 cubic feet of coal lifted. Copper ores exist at BeherakI in the Deogarh subdivision, and lead ores (principally argentiferous galena) occur in the Sankara hills and at Turipahar, Beheraklj and Panchpahar. At BeherakI 29 02. 8 dwt. of silver have been obtained per ton of lead, and at Lakshmipur near Naya Dumka 50 oz. 3 grs. of silver per ton of lead. A considerable area, especially in the Rajmahal Hills, is occupied by laterite, often constituting an excellent iron ore. Siliceous white clays belonging to the coal- measures at Lohandia in the Hura coal-field are suitable for the pottery.

Trade and Communication

The arts and manufactures are of a primitive character and of little importance. The manufacture of mattocks, picks, ploughs, hooks, knives, axes, spears, arrows, and shields is carried commutations. on as a villa e industr Y- The iron was formerly smelted from native ore by Kol settlers ; but with the destruction of jungle and the greater facility that now exists for obtaining old scrap-iron cheap from Deogarh and Rampur Hat, the Marayeahs or blacksmiths of the District no longer use locally smelted iron or steel, Bais or measuring cups of a pretty though stereotyped pattern are made on a limited scale by Thatheris and Jadapetias (braziers). Mochis and Chamars carry on a fairly extensive industry in tanning leather and making shoes ; Doms, Haris, and Santals cure skins for exportation; Mahlis make baskets, bamboo mats, and screens; Tatwas and Jolahas weave coarse cotton cloths ; and Kumhars make tiles, pots, and pans. The manufacture of ghi, oil (inahua, sarguja, and mustard), and gur or coarse sugar is carried on as a domestic industry. Tasar cocoons are grown throughout the District, and spinning and weaving are also carried on. The lac insect is reared on palas trees on a fairly large scale ; a Marwari at Dumka manufactures about 700 maunds of shellac per annum for export, and there are other factories in the neighbourhood of Dumka and at Pakaur, while lacquered bangles are manufactured at Nunihat and a few other places. Village carpenters are numerous, and wood-carving is carried on to a very small extent. Silver and pewter ornaments are also made.

Indigo was till recently manufactured in a few European and native factories, but the industry is now extinct. Brick-making on European methods has been carried on at Maharajpur for the last few years. The chief imports are rice, gunny-bags, raw cotton, sugar refined and unrefined, molasses, European and Bombay piece-goods, salt, kerosene oil, coal and coke. The chief exports are food-grains, linseed and mustard seed, sabai grass, road-metal, hides, raw fibres, and tobacco.

Trade is carried on at markets, and is almost exclusively in the hands of traders from Bihar and Marwari merchants. The principal entrepot is Sahibganj. About 200,000 maunds of sabai grass are exported to the paper-mills near Calcutta, the approximate value of the export being 4 lakhs. Road-metal is exported chiefly to Calcutta, Hooghly, and Burdwan. The trade in hides is chiefly carried on in the head- quarters and Pakaur subdivisions.

Famine

The District is traversed on the east by the loop-line and on the west by the chord-line of the East Indian Railway. The Giridih branch leaves the chord-line at Madhupur within the District, and there is also a short branch connecting Rajmahal on the Ganges with the loop-line. A small branch line from Baidyanath junction to Deogarh is worked by a private company. The construction of a line from Bhagalpur to Hansdiha by a private syndicate was sanctioned, but the concession lapsed before the necessary capital was raised. There are also projects for the construction of lines from Bhagalpur to Deogarh, from Ahmadpur to Baidyanath, and from Mangalpur via Suri to Dumka. The District possesses good roads by which its produce is carted to the railway; 848 J miles being maintained by the District road committee, in addition to village roads and roads in Government estates. The chief roads are the Bhagalpur-Suri road passing through

Dumka, the Suri-Monghyr road passing through Deogarh, the roads from Dumka to Rampur Hat and to the different subdivisional head- quarters, the road from Murshidabad along the Ganges through Rajmahal and Sahibganj to Bhagalpur, as well as several connecting cross-roads and feeder roads to the railway stations. The Ganges, which skirts the north-east of the District, forms an important channel of communication, but the other streams of the District are of no commercial importance.

The District has thrice suffered from famine within the last fifty years. On occasions of scarcity the mahua and the mango trees afford food for large numbers ; but in 1865-6, when there was great scarcity and distress, the people were compelled by hunger to eat the mangoes while still unripe, and thou- sands of deaths from cholera resulted. In 1874 relief was afforded by Government on a lavish scale, the fruit was allowed to ripen before being plucked, and there was no outbreak of disease. In 1896-7 part of the Jamtara subdivision and the whole of the Deogarh subdivision were declared affected. Relief works were opened in Jamtara and in Deogarh ; but the highest average daily attendance in Jamtara was only 3,258, in the third week of May, 1897, and in Deogarh 1,647, towards the end of June. The works were finally closed on August 15, after an expenditure of Rs. 29,000 on works and Rs. 25,000 on gratuitous relief.

Administration

For administrative purposes the District is divided into six sub- divisions, with head-quarters at DUMKA, DEOGARH, GODDA, RAJ- MAHAL, PAKAUR, and JAMTARA. A Joint-Magistrate or Deputy-Magistrate-Collector is usually in charge of the Rajmahal subdivision, and a Deputy-Magistrate-Collector of each of the other subdivisions ; in addition, three Deputy-Magistrate- Collectors and a Sub-Deputy-Magistrate-Collector are stationed at Dumka, and one Deputy-Magistrate-Collector and one Sub-Deputy- Magistrate-Collector at Rajmahal, Deogarh, and Godda, and one Sub -Deputy -Magistrate -Collector at Jamtara and Pakaur. These officers have civil and criminal jurisdiction as detailed in the follow- ing paragraph. The Deputy-Commissioner is vested ex offido with the powers of a Settlement officer under the Santal Parganas Regulation III of 1872, and is also Conservator of forests. An Assistant Con- servator of forests is stationed in the District.

The civil and criminal courts are constituted under Regulation V of 1893, as amended by Regulation III of 1899. The Sessions Judge of Birbhum is Sessions Judge of the Santal Parganas and holds his court at Dumka. Appeals against his decisions lie to the High Court of Calcutta. The Deputy-Commissioner exercises powers under sec- tion 34 of the Criminal Procedure Code and also hears appeals from all Deputy-Magistrates. In all criminal matters, except in regard to cases committed to the Court of Sessions and proceedings against Euro- pean British subjects, the Commissioner of Bhagalpur exercises the powers of a High Court. Suits of a value exceeding Rs. 1,000 are tried by the Deputy-Commissioner as District Judge, or by subdivi- sional officers vested with powers as Subordinate Judges. These courts are established under Act XII of 1887, and are subordinate to the High Court of Calcutta. Suits valued at less than Rs. 500 are tried by Deputy- and Sub-Deputy-Collectors sitting as courts under Act XXXVII of 1855, an appeal lying to the subdivisional officer.

That officer can try all suits cognizable by courts established under Act XXXVII of 1855, and an appeal against his decision lies to the Deputy-Commissioner. There is no second appeal where the appellate court has upheld the original decree ; if, however, the decree has been reversed, a second appeal lies to the Commissioner of the Division. The Deputy-Commissioner and Commissioner have powers of revision. These courts follow a special procedure, thirty-eight simple rules re- placing the Code of Civil Procedure. A decree is barred after three years ; imprisonment for debt is not allowed ; compound interest may not be decreed, nor may interest be decreed to an amount exceeding the principal debt. When any area is brought under settlement, the juris- diction of the courts under Act XII of 1887 is ousted in regard to all suits connected with land, and such suits are tried by the Settle- ment officer and his assistants or by the courts established under Act XXXVII of 1855 ; the findings of a Settlement court have the force of a decree. The District is peaceful, and riots are almost unknown. Persons suspected of witchcraft are sometimes murdered ; cattle-theft is perhaps the most common form of serious crime.

The current land revenue demand in 1903-4 was 3-84 lakhs, of which t-i6 lakhs was payable by 449 permanently settled estates, Rs. i, 600 by 5 temporarily settled estates, and 2-66 lakhs by 9 estates held under direct management by Government. Of the latter class, the DAMAN-I-KOH is the most important.

Under Regulation III of 1872 a Settlement officer made a settle- ment of the whole District between the years 1873 and 1879, defining and recording the rights and duties of landlord and tenants, and where necessary fixing fair rents. One of the results of this settlement was to preserve the Santal village community system, under which the village community as a whole holds the village lands and has collective rights over the village waste ; these rights, which have failed to secure recog- nition elsewhere in Bengal, were recorded and saved from encroach- ment. As regards villages not held by a community, the custom prevailed of leasing them to mustajirs, a system which led to great abuses, and there was also a tendency for the zammdar to treat the Santal manjhi as though he were but a lessee or mustajir. By the

VOL. XXII. F police rules of 1856 a mandal or headman was elected for each village where the zamindar's mustajir was not approved by the Magistrate and villagers, his duties consisting of the free performance of police and other public duties. As, however, it was unsatisfactory to have two heads to a village, the zemindar's mustajir and the ryot mandal gradually merged into one, with the result that a mustajir, when appointed, had to secure the approval of the Magistrate, mmlndars, and villagers. The position of the headman thus developed was denned at the settlement : he has duties towards the mmindar, the ryots, and the Magistrate; he may be dismissed by the last-named personage on his own motion or on the complaint of the mmlndar or ryots ; and the stability of tenure secured by Regulation III of 1872 prevents the mmlndar from ousting him. The rights of a head- man are not usually transferable, but in the Deogarh subdivision some headmen known as w#/-ryots are allowed to sell their interest in a vil- lage. In 1887 Government passed orders to prevent the sale of ryots' holdings being recognized by the courts in areas in which no custom of sale had been proved. In 1888 the revision of the settlement of 1873-9 m certain estates was undertaken, and the work is being gradually extended throughout the District.

Prominent among the unusual tenures of the District are the ghdt- walis of tap fa Sarath Deogarh, which cover almost the whole Deogarh subdivision and are also found in Jamtara and Dumka. These are police tenures, originally established by the Muhammadan government to protect the frontier of Bengal against the Marathas.

Cultivable land is divided geneially into five classes : three kinds of dkani or rice land, and two kinds of bari or high land. Dhani lands are classified according to the degree by which they are protected from drought, and the average rates or rent may be said to be for the first class Rs. 3, for the second Rs. 2, and for the third R. i. First-class bari land is the well-manured land near the homesteads, averaging R. i ; while second-class bari lands include the remainder of the cul- tivation on the dry uplands, and average 4 annas, Rates vary widely and the averages are only an approximation. In the recent settlement, the average rent for dhani land over 600 acres of typical zamtndari country was Rs. i-i r per acre, and for bari land 6 annas, and the corresponding figures for the Daman-i-koh were Rs. 1-9 and R. 0-5-4. Ryots have, however, been allowed abatements in the settlement actually concluded, and the settled rents do not average more than Rs. 1-8 an acre for dhani lands, and 8 annas for bari land. In the Daman-i-koh the average holding of a cultivator is 9-| acres, of which 4| acres are dhani land ; the total average rent rate is Rs. 8-14, but the average rent settled is only Rs. 6-r per holding. In private settled estates the rents payable are somewhat higher.

The following table shows the collections of land revenue and of total revenue (principal heads only), in thousands of rupees, for a series of years :

Until 1901 the roads were managed by a Government grant adminis- tered by the Deputy-Commissioner; but in that year the Cess Act was introduced and a road cess committee was constituted, with the Deputy-Commissioner as chairman, which maintains the roads outside the municipal areas of Dumka, Deogarh, and Sahibganj.

The drainage of a marsh near Rajmahal was undertaken in 1898 under the provisions of the Drainage Act, and the work is now nearly completed,

The District contains 13 police stations or thanas and 5 outposts. The District Superintendent has jurisdiction in Dumka town, the Deogarh subdivision, and the parts of Pakaur, Rajmahal, and Godda outside the Daman-i-koh. The force subordinate to him in 1903 consisted of 6 inspectors, 28 sub-inspectors, 33 head constables, and 335 constables. In addition to these, a company of military police, 100 strong, is stationed at Dumka. The remainder of the District is excluded from the jurisdiction of the regular police j and police duties are performed under the police rules of 1856 by the village headman, a number of villages being grouped together under a parganait> ghat- wa/ t or sardar, who corresponds to a thana officer. The parganait is the Santal tribal chief, the ghdtwal a police service-tenure holder, and the sardar a Paharia tribal chief. As these indigenous police officials did not satisfactorily cover the whole non-police area, Regulation III of 1900 was passed, under which stipendiary sardars are appointed to groups of villages, where there is no existing and properly remuner- ated officer, and are paid by a cess on the villagers. There are in the Daman-i-koh 33 parganaits and 20 hill sardars. Excluding these, there are in the Dumka subdivision 55 stipendiary sardars ; 4 ghat sardars remunerated by holdings of land, and 819 chaukldars -, and in the Jamtara subdivision 2 ghatwals t 27 sardars ', and 523 chaukldars. In all, chaukldars number 3,965. A District jail at Dumka has accom- modation for 140 prisoners, and subsidiary jails at Deogarh, Godda, Rajmahal, Jamtara, and Pakaur for 116.

Education is very backward, only 2-5 per cent, of the population (4-7 males and 0-2 females) being able to read and write in 1901 ; but progress has been made since 1891, when only 2-8 per cent, of the males were literate. The number of pupils under instruction increased

F 2 from about 17,000 in 1883 to 18,650 in 1892-3, to 22,755 in 1900-1, and to 27,284 in 1903-4, of whom 1,314 were females. In that year, 9-3 per cent, of the boys and 0-95 per cent, of the girls of school- going age were at school. The educational institutions consisted of 26 secondary, 912 primary, and 90 special schools, among which may be mentioned a training school for gurus at Taljhari under the Church Missionary Society, a training school at Benagaria under the Lutheran Mission, and the Madhupur industrial school maintained by the East Indian Railway Company. A special grant of Rs. 9,500 is annually made by Government to encourage primary education among the Santals, and 5,555 aborigines were at school in 1900. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was i*8r lakhs, of which Rs. 78,000 was contributed from Provincial revenues, Rs. 1,100 from municipal funds, and Rs, 45,000 from fees.

In 1903 the District contained 10 dispensaries, of which 7 had accommodation for 89 in-patients. The cases of 60,000 out-patients and 800 in-patients were treated, and 2,686 operations were performed.

The expenditure was Rs. 15,000, of which Rs. 5,000 was met from Government contributions, Rs. 1,000 from Local and Rs. 2,300 from municipal funds, and Rs. 6,000 from subscriptions. Two of the dis- pensaries in the Daman-i-koh are maintained by an annual subscrip- tion among the Santals of an anna per house, Government providing the services of a civil Hospital Assistant. In addition, the various missionary societies all maintain private dispensaries. The Raj Kumari Leper asylum, a well-endowed institution with substantial buildings, is managed by a committee of which the Deputy-Commis- sioner is chairman.

Vaccination is compulsory only in municipal areas. In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 76,000, or 42-5 per 1,000.

[Sir W. W. Hunter, Statistical Account of Bengal, vol. xv (1877), and Annals of Rural Bengal (1868) ; W. B. Oldham, Santdl Parganas Manual (Calcutta, 1898); H. H. Heard, Ghatwali and Mul-ryoti Tenures as found in Deogarh (Calcutta, 1900); F. B. Bradley-Birt, The Story of an Indian Upland (1905).]