Multan District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Multan District

Physical aspects

District in the Multan Division of the Punjab, lying between 29° 22' and 30° 45' N. and 71° 2' and 72° 52' E., with an area of 6,107 square miles. It consists of an obtuse wedge of land, enclosed by the confluent streams of the Chenab and the Sutlej, which unite at its south-western extremity. The irregular triangle thus cut off lies wholly within the Bari Doab ; but the District boundaries have been artificially prolonged across the Ravi in the north, so as to include a small portion of the Rechna Doab. It is bounded on the east by Montgomery and on the north by Jhang ; while beyond the Chenab on the west lies Muzaffargarh, and beyond the Sutlej on the south the State of Bahawalpur. The past or present courses of four of the great rivers of the Punjab determine the conformation of the Multan plain. At present the Sutlej forms its southern and the Chenab its north-western boundary, while the Ravi intersects its extreme northern angle. Along the banks of these three streams extend fringes of alluvial riverain, flooded in aspects

the summer months, and rising into a low plateau watered by the inundation canals. Midway between the boundary rivers, a high dorsal ridge enters the District from Montgomery, forming a part of the sterile region known as the Bar. It dips into the lower plateau on either side by abrupt banks, which mark the ancient beds of the Ravi and Beas. These two rivers once flowed for a much greater distance southward before joining the Chenab and the Sutlej than is now the case ; and their original courses may still be distinctly traced, not only by the signs of former fluvial action, but also by the existence of dried-up canals. The Ravi still clings to its ancient watercourse, as observed by General Cunningham, and in seasons of high flood finds its way as far as Multan by the abandoned bed. During the winter months, however, it lies almost dry. It is chiefly interesting for the extraordinary reach known as the Sidhnai, a cutting which extends in a perfectly straight line for 10 or 12 miles, as to whose origin nothing can be said with certainty. The Chenab and Sutlej, on the other hand, are imposing rivers, the former never fordable except in exceptionally dry winters, the latter only at a few places. Near their confluence the land is regularly flooded during the summer months.

The District contains nothing of geological interest, as the soil is entirely alluvial. The flora combines species characteristic of the Western Punjab, the trans-Indus country, Sind, and Rajputana, but has been much changed, since Edgeworth's Flonila Alallka was written, by extension of canal-irrigation. The date-palm is largely cultivated, and dates are exported. A variety of mango is also grown, with a smaller and more acid fruit than the sorts reared in Hindustan and the submontane Punjab.

Wolves are not uncommon, while jackals and foxes are numerous. The antelope most frequently met with is the 'ravine deer' (Indian gazelle), but nilgai are also seen.

The heat and dust of Multan are proverbial ; but on the whole the cHmate is not so bad as it is sometimes painted, and, as else- where in the Punjab, the cold season is delightful. The hot season is long : and, during the months in which high temperatures are recorded, Multan is only one or two degrees below Jacobabad. Though elsewhere the mean temperature may be higher, there is no place in India, except Jacobabad, where the thermometer remains high so consistently as at Multan. The nights, however, are com- paratively cool in May, the difference between the maximum and minimum temperatures sometimes exceeding 40". The general dry- ness of the climate makes the District healthy on the whole, though the tracts liable to flood are malarious. The rainfall is scanty in the extreme, the average varying from 4 inches at Mailsi to 7 at Multan.

The greatest fall recorded during the twenty years ending 1903 was i9'9 inches at Multan in 1892-3, and the least 1-3 inches at Lodhran in 1887-8. Severe floods occurred in 1893-4 and 1905.

History

The history of Multan is unintelligible without some reference to its physical history, as affected by the changes in course of the great rivers ^ Up to the end of the fourteenth century the Ravi seems to have flowed by Multan, entering the Chenab to the south of the city. The Beas flowed through the middle of the District, falling into the Chenab, a course it appears to have held until the end of the eighteenth century; while possibly as late as 1245 the Chenab flowed to the east of Multan. It has also been held that in early times the Sutlej flowed in the present dry bed of the Hakra, some 40 miles south of its present course. ^^' hen the District was thus intersected by four mighty rivers, the whole wedge of land, except the dorsal ridge of the Bar, could obtain irrigation from one or other of their streams. Numerous villages then dotted its whole surface ; and Al Masudi, in the tenth century, describes Multan, with Oriental exaggeration, as surrounded by 120,000 hamlets.

In the earliest times the city now known as Multan probably bore the name of Kasyapapura, derived from Kasyapa, father of the Adityas and Daityas, the sun-gods and Titans of Hindu mythology. Under the various Hellenic forms of this ancient designation, Multan figures in the works of Hecataeus, Herodotus, and Ptolemy. General Cunning- ham believes that the Kaspeiraea of the last-named author, being the capital of the Kaspeiraei, whose dominions extended from Kashmir to Muttra, must have been the principal city in the Punjab towards the second century of the Christian era. Five hundred years earlier Multan perhaps appears in the history of Alexander's invasion as the chief seat of the Malli, whom the Macedonian conqueror utterly subdued after a desperate resistance. He left Philippus here as Satrap ; but it seems probable that the Hellenic power in this distant quarter soon came to an end, as the country appears shortly afterwards to have passed under the rule of the Maurya dynasty of Magadha. At a later period Greek influence may once more have extended to Multan under the Bactrian kings, whose coins are occasionally found in the District. In the seventh century a, n. Multan was the capital of an important province in the kingdom of Sind, ruled by a line of Hindu kings known as the Rais, the last of whom died in 631. The throne was

' A. runningham, Geography of India, pp. 221-2; Kavcity '\n Journal. AstatiL Society, Bciv^aL vol. ixi, itiyJ ; and Olclliam, Calcutta Kcview, vul. lix, ib74. iheii usurped b)' a Brahman named Chaeh, who was in power when the Arabs first appeared in the valley of the Indus. During his reign, in 641, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, Hiuen Tsiang, visited Multan, where he found a golden image of the Sun. This idol is repeatedly mentioned by the Arab historians, and from it General Cunningham derives the modern name of the city, though other authorities connect it rather with that of the Malli.

In 664 the Arab inroads penetrated as far as Multan : but it was not until 712 that the district fell, with the rest of the kingdom of Sind, before Muhammad bin Kasim, who conquered it for the Khalifas. For three centuries Multan remained the outpost of Islam : but the occupation was in the main military, and there was no general settle- ment of Muhammadan invaders or conversion of Hindu inhabitants till the Ghaznivid period. It was twice again captured by the Arabs, and in 871 the Lower Indus valley fell into the hands of Yakub bin Lais.

Shortly afterwards two independent Muhammadan kingdoms sprang up with their capitals at Mansura and Multan. Multan was visited in 915-6 by the geographer Masudi, who says that 'Multan' is a corruption of Miilasthanapura, by which name it was known in the Buddhist period. He found it a strong Muhammadan frontier town under a king of the tribe of Koresh, and the centre of a fertile and thickly populated district. In 980 the Karmatians took Multan, and converted to their heres\- the family of LodI Pathans, who had by that time possessed themselves of the frontier from Peshawar to Multan. when Mahmiid of Ghazni took Bhatia (probably Uch), Abul Fateh, the Lodi governor of Multan, allied himself with Anand Pal, but sub- mitted in 1006. He again re\olted, and in loio was deported by Mahmud, who made his son Masud governor. Masud released Abul Fateh, who had apparently abandoned the Karmatian tenets : for a letter of 1033, which has been preserved by the Druses, addressed to the Unitarians of Sind and Multan, and in particular to Shaikh bin Sumar of Multan, exhorts them to bring him back into the true faith.

For the next three centuries the history of Multan, as the frontier province of the empire, is practically the history of the Mongol invasions. Owing to the difficulties of the Khyber route and the hostility of the Gakhars, the majority of the invading hordes took the Multan road to Hindustan, until the drying up of the country all along llie Ghaggar made this route impracticable. Between 122 1 and 1528 ten invasions swept through the l^istrict, commencing with the cele- brated flight of Jalal-ud-din Khwarizm and ending with the peaceful transfer of the province to Babar in 1528, while the city suffered sacks and sieges too numerous to detail. During this period Multan was for the most part subject to Delhi, but twice it was a separate and independent kingdom.

On the death of Kutb-ud-din, Nasir-ud-dm Kubacha seized Multan, with Sind and Seistan (1210), and ruled independently till 1227. After successfully resisting a Mongol siege in 1221, Multan was reduced in 1228 by the governor of Lahore under Altamsh, and again became a fief of the Delhi empire. On that emperor's death, its feudatory Izz-ud-din Kabir Khan-i-Ayaz joined in the conspiracy to put Razia on the throne (1236); but though he received the fief of Lahore from her, he again rebelled (1238), and was made to exchange it for Multan, where he proclaimed his independence, and was suc- ceeded by his son Taj-ud-din Abu-Bakr-i-Ayaz (i24i\ who repelled several Karlugh attacks from the gates of the city.

Saif-ud-din Hasan, the Karlugh, unsuccessfully attacked Multan (1236). After his death the Mongols heki the city to ransom (1246), and at last it fell into the hands of the Karlughs, from whom it was in the same year (1249) wrested by Sher Khan, the great viceroy of the Punjab. Izz-ud-dm Balban-i-Kashlu Khan endeavoured to recover Uch and Multan (1252), and succeeded in 1254. Mahmud Shah I bestowed them on Arsalan Khan Sanjar-i-Chast, but Izz-ud-din was reinstated in 1255. He rebelled against the minister Ghiyas-ud-dln Balban (1257), and being deserted by his troops fled to Hulaku in Irak, whence he brought back a Mongol intendant to Multan and joined a Mongol force which descended on the province, and dis- mantled the walls of the city, which only escaped massacre by a ransom paid by the saint Bahawal Hakk (Baha-ud-din Zakariya).

For two centuries the post of governor was held by distinguished soldiers, often related to the ruling family of Delhi, among whom may be mentioned Ghazi Malik, afterwards Ghiyas-ud dm Tughlak. In 1395 Khizr Khan, the governor, a Saiyid, quarrelled with Sarang Khan, governor of Dipalpur, and, being taken prisoner, escaped to join Timur on his invading the Punjab. After being compelled to raise the siege of Uch, Timur's grandson defeated Sarang Khan's forces on the Beas, and invested Multan, which surrendered after a siege (1398), and Khizr Khan was reinstated in his governorship.

After a series of victories over the Delhi generals, Khizr Khan took Delhi and founded the Saiyid dynasty. Some years later Bahlol LodI held the province before seizing the throne of Delhi. In r437 the Langahs, a Pathan tribe recently settled in the District, began to make their power felt ; and in 1445 Rai Sahra Langah expelled Shaikh Yiisuf, a ruler chosen by the people and his own son-in-law, and established the Langah dynasty, which ruled independently of Delhi for nearly 100 years, the Ravi being recognized in 1502 as the boundary between the two kingdoms. Finally, however, the Arghun Turks incited by Babar took Multan in 1527, and in the following year handed it over to him.

Under the Mughal emperors Multan enjoyed a period of peace and prosperity, only disturbed by the rebellion of the Mirzas, who were defeated at Talamba in 1573, and by the flight of Dara Shikoh through the province. The town became the head-quarters of a Subah covering the whole of the South- West Punjab and at times including Sind. Even when the Mughal power began to wane Multan no longer felt the first shock of invasion, the route through Multan and Bhatinda being now too dry to give passage to an army. In 1748 a battle was fought near Multan between Kaura Mai, deputy of Mir Mannu, the governor of the Punjab, and Shahnawaz, who had received a grant of the province from the late emperor Muhammad Shah. Kaura Mai was victorious, but fell later fighting against xVhmad Shah Durrani. Multan in 1752 became a province of the kings of Kabul, ruled for the most part by Pathan governors, chiefly Sadozais, who ultimately founded a virtually independent kingdom. Their rule, however, extended over only half the present District, the southern portion being under the Nawabs of Bahawalpur.

The Marathas overran the province in 1758, but the chief feature of this period was the continual warfare with the Sikhs. From 177 1-9 the Bhangi confederacy held the north and centre of the District, but they were expelled by Timur Shah, and from 1779 to 1818 Nawab Muzaffar Khan Sadozai was in power in Multan. His relations with the Bahawalpur State were strained, and he had to face unassisted the repeated onslaughts of the Sikhs, which culminated in the capture and sack of Multan by RanjTt Singh in 181 8.

After passing through the hands of two or three Sikh governors, Multan was in 182 1 made over to the famous Diwan Sawan Mai. The whole country had almost assumed the aspect of a desert from frequent warfare and spoliation ; but Sawan Mai induced new inhabitants to settle in his province, excavated numerous canals, favoured commerce, and restored prosperity to the desolated tract. After the death of Ranjit Singh, however, quarrels took place between Sawan Mai and Raja Gulab Singh ; and in 1844 the former was fatally shot in the breast by a soldier. His son Mulraj succeeded to his governorship, and also to his quarrel with the authorities at Lahore, till their constant exactions induced him to tender his resignation. After the establish- ment of the Council of Regency at Lahore, as one of the results of the first Sikh War, difficulties arose between Diwan Mulraj and the British officials, which culminated in the murder of two British officers, and finally led to the Multan rebellion. That episode, together with the second Sikh War, belongs rather to imperial than to local history. It ended in the capture of Multan and the annexation of the whole of the Punjab by the British. The city offered a resolute defence, but, being stormed on January 2, 1849, fell after severe fighting ; and though the fort held out for a short time longer, it was surrendered at discretion by Mulraj on January 22. Mulraj was put upon his trial for the murder of the officers, and, being found guilty, was sentenced to death ; but this penalty was afterwards commuted for that of transportation. The District at once passed under direct British rule. In 1857 the demeanour of the native regiments stationed at Multan made their disarmament necessary, and, doubtless owing to this precaution, no outbreak took place.

The principal remains of archaeological interest are described in the articles on Atari, Jalalpur, Kahror, Multan, and Talamba.

Population

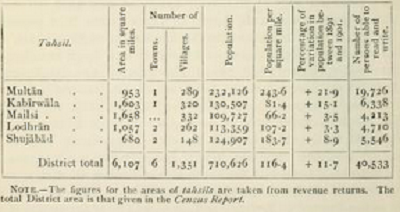

The District contains 6 towns and 1,351 villages. The population at each of the last three enumerations was : (1881) 556,557, (1891) 635,726, and (1901) 710,626. During the last decade opuation. .^ increased by 11-7 per cent., the increase being greatest in the Multan tahsil and least in Lodhran. The increase was largely due to immigration, for which the attractions of the city are partly responsible, and to some extent to the colonization of the Sidhnai Canal tract between 1886 and 1896. The District is divided into five tahsils, Multan, Shujabad, Lodhran, Mailsi, and KabTr- wala, the head-quarters of each being at the place from which it is named. The chief towns are the municipalities of Multan, the administrative head-quarters of the District, Shujabad, Kahror, Talamba, and Jalalpur. The following table shows the chief statistics of population in 1901 : —

Muhammadans number 570,254, or over 80 per cent, of the total; Hindus, 133,560 ; and Sikhs, 4,662. The density of population is very low, but is comparatively high if the cultivated area only be taken into account. The language of the people, often called Multanl, is a form of Western Punjabi.

The most numerous tribe is that of the agricultural Jats, who number 140,000, or 20 per cent, of the total population. Next to them come the Rajputs (92,000), and after them Arains (32,000), cultivators and market-gardeners. Then come the Baloch (24,000), Khokhars (12,00c), and Pathans (8,000). The Saiyids number 11,000, and Kureshis 8,000. Of the commercial classes, the Aroras, who are found in larger numbers in Multan than in any other District of the Province, number 89,000; the Khattrls, who are largely immigrants from the Punjab proper, only 11,000. The Muhammadan Khojas, more numerous here than in any other District in the Punjab except Montgomery and La- hore, number 10,000.

The Bhatias (3,000), though small in num- bers, also deserve mention as a commercial caste. Of the artisan classes, the Julahas (weavers, 27,000), Mochis (shoemakers and leather-^ workers, 24,000), Kumhars (potters, 19,000), and Tarkhans (carpenters, 17,000) are the most important ; and of the menial classes, the sweepers (38,000), who are mostly known in this District as Kutanas, Dhobis (washermen, 15,000, known as Charhoas), Machhis (fishermen, bakers, and water-carriers, 12,000), and Nais (barbers, 8,000). The Mlrasis, village minstrels and bards, number 11,000. Other castes worth men- tion are the Mahtams (5,900), of whom the Muhammadan section are generally cultivators, while the Hindus make a living by clearing jungle or hunting game ; Ods (4,000), a wandering caste living by earthwork ; Jhabels (3,000), a fishing and hunting tribe of vagrant habits, living on the banks of the Sutlej ; and Marths (700), also a vagrant tribe found only in this District. About 40 per cent, of the population are supported by agriculture, and 28 per cent, by industries.

The Church Missionary Society began its operations at Multan city in 1855, and the mission school, the oldest in the District, was established there in the following year. The mission also maintains a church, a female hospital, and a branch of the Punjab Religious Book Depot. The American Methodist Episcopal Mission began work at Multan in 1893. The District contained 198 native Christians in 1901.

Agriculture

The soil is of a uniform alluvial composition, with sand everywhere at a greater or less depth from the surface ; and the chief distinction of soils depends on the proportions in which the sand . . , and clay are mtermixed, though there are also some tracts of salt-impregnated earth. From an agricultural point of view, however, all distinctions of soil are insignificant compared with that between irrigated and unirrigated land, and the agricultural conditions depend almost entirely on the quality and quantity of irrigation.

The District is held chiefly by small peasant proprietors, but large estates cover 627 square miles and lands held under temporary leases from Government about 533 square miles. The area for which details are available from the revenue records of 1903-4 is 5,952 square miles, as shown in the table on the next page.

Wheat is the chief crop of the spring harvest, covering 555 square miles in 1903-4. Gram and barley covered only 40 and 21 square miles respectively. The great and spiked millets {jowdr and bdjra) are the principal staples of the autumn harvest, covering 94 and 58 square miles ; and pulses occupied 69 square miles. There were 26 square miles under indigo, 20 under rice, and 102 under cotton. Very little sugar or maize is grown.

The area under cultivation varies enormously with the character of the season, but the average area sown increased by about 30 per cent, in the twenty years ending 1 901-2, owing to the extension of canal- and well-irrigation. I>oans for the construction of wells are taken readily, and more than 3 lakhs was advanced under the Land Improvement Loans Act during the five years ending 1903-4.

Four breeds of cattle are recognized : the Bhagnari (from Sind), the IMassuwah and Dajal (from Dera Ghazi Khan), and the local breed, which is mostly of an inferior description. Cow buffaloes are kept for milk. Camels are very largely bred, and sheep and goats are common in all parts. Horses and ponies are numerous, but the District is only a moderately good one for horse-breeding. The Army Remount department maintains six horse and eleven donkey stallions, and the District board one donkey and three pony stallions.

Of the total area cultivated in 1903-4, 1,310 square miles, or 85 per cent., were classed as irrigated. Of this area, 123 square miles v/ere supplied from wells, 758 from wells and canals, 417 from canals, and 12 from channels and tanks. In addition, 276 square miles, or 18 per cent, of the cultivated area, are subject to inundation from the Chenab, Sutlej, and Ravi. Three great canal systems irrigate the District : the Sidhnai taking off from the Ravi, the Lower Sutlej Inundation Canals, and the Chenab Inundation Canals. As these canals flow only while the rivers are in flood, they generally require to be supplemented by wells. The District possesses 21,6x5 wells, all worked by Persian wheels, and 3,744 unbricked wells, lever wells, and water-lifts. The latter are largely used for lifting water from river channels.

The District contains 157 square miles of 'reserved' and 2,323 of ' protected ' forests, under the Deputy-Conservator of the Multan Forest division. These forests are chiefly waste land covered with scrub and scattered trees. Avenues of shlsham {Dalbergia Sissoo) are found along the roads and canals, and the date-palm is grown largely, considerable quantities of the fruit being exported. The revenue from forests under the Forest department in 1903-4 was 1-2 lakhs.

Trade and communication

Saltpetre is manufactured to some extent, and a little katikar is found. Impure carbonate of soda is also made from the ashes of Haloxylon recurvum, which grows wild in considerable quantities.

The industrial products for which the city of Multan is noted are glazed pottery, enamelling on silver, silver ornaments, cotton and woollen carpets, silk fabrics, mixed textures of cotton and silk, cotton printing, metal-work, and ivory- turning. The glazed pottery work, which used to be confined to the manufacture of tiles, now largely takes the form of ornamental vases, plaques, &:c., and the enamelling industry is on the increase. The manufacture of carpets has greatly fallen off. ISIultan is second only to Amritsar in the manufacture of silk, and over 40,000 yards of silk fabrics and 200,000 of silk and cotton mixtures are produced annually. A large number of ivory bangles are turned. The metal-work consists chiefly of the manufacture of dispatch boxes and uniform cases, which is a rapidly growang industry. Cotton cloth is woven, and a once flourishing paper manufacture still lingers. Multan city has a railway workshop, with 315 employes in 1904; and 10 cotton-ginning and 3 cotton-pressing factories, with a total of 657 hands. At Shujabad a ginning factory employs 21 hands, and at Rashida on the North-Western Railway a ginning factory and cotton- press employs 150.

The District exports wheat, cotton, indigo, bones, hides, and car- bonate of soda ; and imports rice, oilseeds, oil, sugar, ght, iron, and piece-goods. The imports of raw wool exceed the exports, but cleaned wool is a staple of export. The chief items of European trade are wheat, cotton, and wool. Multan city is the only commercial place of importance, and has long been an important centre of the wheat trade.

The District is traversed by the North-Western Railway main line from Lahore to Karachi, which is joined by the Rechna Doab branch from Wazlrabad and Lyallpur at Khanewal. After reaching Multan city the line gives off the branch running through Muzaffargarh, along the Indus valley, which leaves the District by a bridge over the Chenab. It then turns south, and enters Bahawalpur by a bridge over the Sutlej. The total length of metalled roads is 31 miles and of unmetalled roads 1,199 miles ; of these, 13 miles of metalled roads are under the Public Works department, and the rest are maintained by the District board. There is practically no wheeled traffic, goods being carried by camels, donkeys, or pack-bullocks. The Chenab is crossed by ten ferries, the Sutlej by thirty-one, and the Ravi by twelve. There is but little traffic on these rivers.

Famine

Before British rule cultivation was confined to the area commanded by wells, and though drought might contract the cultivated area and cause great loss of cattle, real famine could never occur. the extension or cultivation that has taken place since annexation has followed the development of irrigation by wells and canals; and though considerable loss of cattle is still incurred in times of drought, the District is secure from famine, and exports wheat in the worst years. The area of crops matured in the famine year 1899-1900 amounted to 75 per cent, of the normal.

Administration

The District is in charge of a Deputy-Commissioner, aided by two Assistant or Extra-Assistant Commissioners and two Revenue Assistant .Commissioners, of whom one is in charge of the District treasury. It is divided for general administrative purposes into the five tahsil of MuIultan, Shujabad, Lodhran, Mahsi, and KabIrwala, each under a tahs'ildar assisted by two naib-tahsildars. Multan city is the head-quarters of a Superintending Engineer and two Executive Engineers of the Canal department, and of an Extra- Assistant Conservator of Forests.

The Deputy-Commissioner as District Magistrate is responsible for criminal justice. Civil judicial work is under a District Judge; and both officers are supervised by the Divisional Judge of the Multan Civil Division, who is also Sessions Judge. There are two Munsifs, both at head-quarters. Cattle-theft is the principal crime of the District, but burglary is also becoming common. Cattle-lifting is regarded as a pastime rather than a crime, and proficiency in it is highly esteemed.

The greater part of the District was administered for twenty-three years by Diwan Sawan Mai. He adopted the system usual with native rulers of taking a share of one-third, one-fourth, or one-sixth of the produce, or else a cash assessment based on these proportions but generally calculated a little higher than the market rate. Cash rates per acre were levied on the more valuable crops. Another form of assessment was the lease or paffa, under which a plot of 15 to 20 acres, generally round a well, paid a lump annual sum of Rs. 12 or more. In addition, many cesses and extra dues were imposed, until the uttermost farthing had in some way or other been taken from the cultivator.

On annexation, the first summary settlement was made at cash rates fixed on the average receipt of the preceding four years. Prices, however, had fallen ; and the fixity of the assessment, added to the payment in cash, pressed hardly on the people, and the assessment broke down. The second summary settlement made in 1853-4, despite reductions and attempts to introduce elasticity in collections, did not work well. In 1857-60 a regular settlement was undertaken.

A fixed sum was levied in canal areas, amounting to 16 per cent, below the previous assessment, to allow for varying conditions. It was estimated that about 54 per cent, of the revenue might require to be remitted in bad years. In point of fact remissions were not given, but the assess- ment was so light that this was not felt. In 1873 a revised settlement was begun. The new revenue was 86 per cent, of the half ' net assets,' and an increase of 40 per cent, on the last demand. A fluctuating system, which made the assessments depend largely on actual cul- tivation, was definitely adopted in riverain tracts, and the system of remission proposed at the regular settlement was extended in the canal areas.

The current settlement, completed between 1897 and 1901, was a new departure in British assessments, though the resemblance to Sawan Mai's system is notable. On every existing well is imposed a lump assessment, which is classed as fixed revenue, and paid irre- s])ective of the area from time to time irrigated by the well ; if, however, the well falls out of use for any cause, the demand is remitted. All cultivation other than that dependent entirely on well-water pays at fluctuating rates, assessed on the area matured in each harvest. Thus, although the revenue is approximately 92 per cent, of the half 'net assets,' and the demand of the former settlement has been more than doubled, there is no fear of revenue being exacted from lands which have no produce to pay it with. The crop rates vary from Rs. 3-5 per acre on wheat, tobacco, &c., to Rs. 2-2 on inferior crops. The demand, including cesses, was 17-5 lakhs in 1903-4. The average size of a proprietary holding is 8-3 acres.

The collections of land revenue alone and of total revenue are shown below, in thousands of rupees : — These figures are for the financial year ending March .^i, 1904. The demand figures given above (17-5 lakhs, incJuding cesses) are for the agricultural year, and include the revenue demand for the spring harvest of 1904, wliich was \ery much higher than that for the corresponding harvest of 1903.

The District contains five municipalities, Multan, Shujabab, Kah- KOR, Talamba, and Jalalpur ; and one ' notified area,' Dunyapur. Outside these, local affairs are managed by the District board. The expenditure of the board in 1903-4 was i-i lakhs, education being the largest individual item. Its income, which is mainly derived from a local rate, slightly exceeded the expenditure.

The regular police force consists of 804 of all ranks, including 41 cantonment and 252 municipal police, under a Superintendent, who usually has one Assistant Superintendent and 5 inspectors under him. The village watchmen number 943. The District is divided into 18 police circles, with 5 outposts and 9 road-posts. The District jail at head-quarters has accommodation for 743 prisoners. It receives pri- soners sentenced to terms not exceeding three years from the Districts of Multan and Muzaffargarh, and in the hot season from Mianwali. The Central jail, situated 4 miles outside the city, is designed to hold 1,197 prisoners. Convalescents from all jails in the Punjab are sent here.

Multan stands third among the twenty-eight Districts of the Province in respect of the literacy of its population. In 1901, 5-7 per cent, of the population (lo-i males and 0-4 females) could read and write. The high proportion of literate persons is chiefly due to the Hindus, among whom education is not, as elsewhere, practically denied to the lower castes. The number of people under instruction was 3,684 in 1880-1, 7,355 in 1890-1, 8,156 in 1900-1, and 8,881 in 1903-4. In the last year the District had one training, one special, 13 secondary and 82 primary (public) schools, and 26 advanced and 141 elementary (private) schools, with 296 girls in the public and 166 in the private schools. The chief institutions are a Government normal school and three high schools at Multan city. The District also possesses five zaniinddri schools, where special concessions are made for the purpose of extending education to the agricultural classes. There is a school of music (unaided) for boys at Multan. The expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 89,000, of which fees contributed Rs. 25,000, municipalities Rs. 16,000, the District fund Rs. 19,000, and Provincial revenues Rs. 22,000, the rest coming from subscriptions and en- dowments.

Besides the civil hospital, two city branch dispensaries, and the Victoria Jubilee Hospital for women in Multan city, the District pos- sesses eight outlying dispensaries. At these institutions, 119,044 out- patients and 2,510 in-patients were treated in 1904, and 6,153 operations were performed. The Church Missionary Society also maintains a female hospital at Multan. The total expenditure in 1904 was Rs, 27,000, Rs. 16,000 being contributed by District and municipal funds in equal shares.

The number of persons vaccinated in 1903-4 was 27,700, repre- senting 39 per 1,000 of the population. Vaccination is compulsory in Multan city.

[E. D. Maclagan, District Gazetteer (190 1-2); Settlement Report (1901) ; and ' Abul Fazl's Account of the Multan languages Journal As. Soc. of Bengal {1901), p. i; Saiyid Mwhdimma.d'Latif , Early History of Multan (1891); C. A. Roe, Customary Law of the Mtiltdti District (revised edition, 1901); Yj. 0'^ne.x\, Glossary of the Miiltdnl Language, revised edition, by J. Wilson and Pandit Hari Kishan Kaul (1903).]