Sonali Dasgupta

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

Contents |

The real woman

Sonali Dasgupta, the real woman behind the scandal

Malini Nair, The Times of India TNN | Jun 8, 2014

Sonali lived a full life in Rome, a feisty, independent and successful businesswoman who ran an India-inspired boutique - probably the first such in Rome of the early 60s — and remained an integral part of the city's social and cultural circuit. Her clothes, jewellery, furnishings and handicrafts sold at Sonali, her store, were much sought after and her clientele included the film fraternity of Itlay and Hollywood. And she certainly remained in touch with her family back home.

The only people who have the right to be betrayed/outraged by her decision to walk out on her first marriage, her siblings and children, have long put it behind them. A talk with them is enough to debunk the media myth of the miserable recluse. "As her family, we are all tired of reading the same old story of her and Rossellini," says her niece Sukanya Wignarajan, a psychotherapist based in Tokyo.

Sonali was closest to her youngest and only brother, Karun Senroy, an engineer who now lives in Ventabren, close to Aix-en-Provence, in southern France. He laughs away the stories about her insular existence. "She was close to all her siblings, one in Oxford and another in Kolkata. She travelled with her daughter, Raffaella, to India to visit our parents in Lucknow. She was not 'cut off' as it has been written about her. Her son, Gil, used to travel to India on a regular basis on business. He made it a point to visit his grandmother (my mother) in India," he says.

In an interview to Calcutta Times, her grandson Birsa Dasgupta, says this of the very dramatic episode in the family's history. "There's never been a hush-hush about it because we, Dasguptas and Rossellinis, don't treat it as a scandal... The first person in the family who made me aware of why my thamma doesnt live with us was my dadon Harisadhan. He made me understand that there's a part of our family in Rome which thamma has to run and take care of so between the two of them they have decided to split to take up separate responsibilities."

By all accounts, Sonali was an extremely reserved person, and became more so in the aftermath of the scandal and howls of outrage that followed her flight to Rome. But she was far from being a reclusive wreck. Nor was she Rossellini's social shadow. She was a celebrity in the cinema circuits thanks to him but she was very much her own person as well. Even after her relationship with him crumbled, she remained a known and respected name in her city.

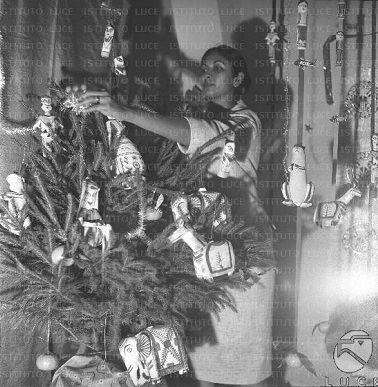

In the early 60s when Indian handlooms and crafts was barely the craze it is now in Europe she set up Varuna, a shop on Via Borgognona, a fashionable street in Rome. Initially she worked with a partner but then took charge of it on her own. According to Senroy, she juggled home and work with skill, running the store single-handedly. And making several trips to India to find the cottons and silks she needed for her designs.

"She was very involved with her work, engaged with every aspect of it. She was very, very happy at her store," says Senroy.

Sonali's engagement with design started early as a student of art and music at Shantiniketan. She came from a family of Bengalis settled in Benares for four generations by the time of her birth. Her father was a civil surgeon and the four siblings travelled around the small towns of Uttar Pradesh.

Sonali married early and became a mother in her early 20s, with little time to engage in a career. She was passionate about Indian handlooms. Wignarajan talks of her incredible collection of Indian silks and cottons from Odissa and south India. And the pride she took in each of them. "They meant a lot to her," she says.

The eye for design translated into her work at Sonali, as she renamed her store. Wignarajann remembers the sketchbook of daywear and formal wear her aunt showed her as a child. In sepia tinted photographs of the time you can see her at the store in Rome, shod in the most elegant Indian silks and woollens, a walking advertisement for her work.

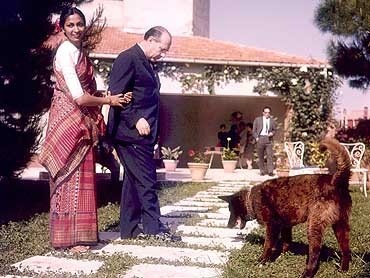

"She always wore saris, always. My uncle who went to meet her in Rome off and on recalls that in the Rome of the 60s she drew attention — 5'8", slender and elegant in beautiful silks," says her niece.

She didn't live a life of disgraced exile from her roots. "She remained an Indian, always. Very much so. She visited for business, kept in touch with her associates, family. Till illness forced her shut her business some years ago. Then she would spend time collecting, reading, writing," says her brother. "A lot of stuff written about her was worthless."

If you [see] a photograph of her at her storefront with a young man. There are Indian artifacts on display and she is looking at them. There is pride in her face and excitement. This certainly was no life led in the perpetual shadow of scandal.

End of the Roman holiday

Dileep Padgaonkar

The Times of India Jun 08 2014

It was the scandal of the '50s: a doe-eyed Bengali beauty leaves husband, child to elope with celebrated Italian filmmaker Roberto Rossellini. But for Sonali Dasgupta, who died in Rome on Jun 07 2014, the love story didn't have a happy ending

Except for a few months in 1957, when she was thrown in the vortex of a scandal that made headlines in the yellow press across the world, Sonali Dasgupta lived her life behind a thick veil of anonymity. Before the scandal erupted, she led the humdrum existence of a housewife, resigned, unhappily no doubt, to playing second fiddle to her husband, Harisadhan Dasgupta, a gregarious, ambitious and talented documentary filmmaker.

She had studied at Shantiniketan and took a lively interest in Indian culture.

But no opportunity came her way to turn that interest into a vocation. Her lot was to bask in the reflected glory of Harisadhan – first in Kolkata, where he had founded a film society along with Satyajit Ray and Chidananda Dasgupta, and later in Mumbai, where he directed documentaries for the Films Division and for major business houses.

His success allowed him to socialise with Mumbai’s commercial film industry circles, including, especially, with fellow Bengalis like Bimal Roy who happened to be a relation as well. It is at a film party, held in December 1956, that he learnt of the imminent arrival in Mumbai of Roberto Rossellini, the great Italian film director, to direct, at the behest of Jawaharlal Nehru, several documentaries, and perhaps also a feature film, to mark ten years of India’s independence. All that mattered to him now was a chance to serve as an assistant to Rossellini. That would be another feather in his cap.

But that was not to be since he was in the midst of shooting a film for a corporate house. So he tried another tack: persuade Rossellini to hire Sonali to help him write the scripts for his films even though she had no experience in script-writing.

Nor did she fancy herself in that role.

Not that Rossellini, whose marriage to Ingrid Bergman was on the rocks, needed much persuasion. The very first time that he set his eyes on Sonali he was seized by a mighty passion to seduce her.

In his eyes, her beauty, intelligence, grace and, not least, her wondrous enigma incarnated the very soul of India.

Discomfited yet flattered by the attention Rossellini lavished on her, Sonali succumbed to the charms of the Italian.

Her chagrined and outraged husband threw her out of the conjugal home. Soon two scandal sheets – RK Karanjia’s Blitz and Baburao Patel’s Filmindia – ran a series of salacious and concocted reports for weeks on end. That prompted Hollywood gossip columnists to join the fray.

Pressure mounted on the government to cancel Rossellini’s visa. It was Nehru who saved the day. He had known Sonali whom he affectionately called Monkey.

She was given a passport and arrangements were made to dispatch her to Paris along with her younger son – then a mere toddler. Rossellini joined her a few weeks later.

Not long afterwards they shifted to Italy where she gave birth to a daughter, opened a fashion boutique that boasted of a high-end clientele, helped Rossellini in his novel film ventures and got along famously with his children from his two previous wives. But the idyll didn’t last long.

One tragedy after another marked her final years: Rossellini, estranged from her, succumbed to a heart attack; Harisadhan, wasted by drink, died in appalling penury; Gil, her younger son, passed away after a freak accident. Her daughter, who trained in the theatre, reportedly embraced a rigid form of Islam and migrated to the Middle East.

Padgaonkar met Sonali two days running in Rome while doing research on Rossellini’s sojourn in India. She was poised, serene, stoic. She spoke little. But the little she spoke was singularly free of bitterness, remorse or chagrin. She had fulsome praise for Rossellini’s accomplishments as a filmmaker. But at the end of Padgaonkar’s last conversation with her she also said with just a hint of irony: “Ask me what it means to live with a genius.”

Showcasing India in Rome

Malini Nair TNN

The Rossellini affair so overwhelmed Sonali Dasgupta’s story that it eclipsed every other facet of her life. But the truth is that decades before Indian crafts became big business in Europe, she set up a successful boutique in Rome in the early ’60s which specialized in westernwear crafted from Indian textiles.

The eponymous ‘Sonali’ was located on Via Borgognona, a fashion street in Rome, and sold Indian jewellery, clothes and handicrafts till age forced her to shut it down. Far from being a shadow of Rossellini, she was a feisty businesswoman whose client list included the Italian film fraternity and Hollywood actor John Malkovich.

“She was an independent, self-made woman,” says her brother Karun Senroy over the phone from Ventabren, France. “She managed the store on her own even as she raised her children.” Senroy was the only one of her three siblings who Sonali remained in touch with after her flight to Rome.

Sukanya Wignarajan, her niece, recalls that she took great pride in her collection of handloom saris. Now a Tokyo-based psychotherapist, Wignarajan remembers as a child being shown a design sketchbook by her aunt featuring her sartorial ideas. Sonali, an important part of the city’s social circuit, was perhaps the best advertisement for her store. “In the ’60s, she cut this really uncommon figure in Rome. She was 5’8”, slender, dressed entirely in saris and very elegant. My uncle who worked in Milan said she always drew a lot of attention,” says Wignarajan.

In the last few years, she busied herself with writing. “She was always a reserved person, unless you goaded her to talk,” says Senroy. “But she was always Indian, very, very much so.”

Jean Herman’s recollections

Shedding light on Rossellini-Sonali Dasgupta affair

Dileep Padgaonkar The Times of India Jun 18 2015

In June 1955, an affair between the great Italian film director, Roberto Rossellini, then married to Ingrid Bergman, and a young Bengali woman, Sonali Dasgupta, wife of the filmmaker Harisadhan Dasgupta, made headlines in the yellow press in India and in Britain and America.

One individual who witnessed the scandal from its genesis to its denouement -a young Frenchman called Jean Herman, later renowned as a prolific and much acclaimed novelist, filmmaker and screen-play writer under the name Jean Vautrin --passed away at his home in village near Bordeaux in south-west France in June 2015 .

Dileep Padgaonkar was privileged to get his account of what had transpired during those turbulent months in the course of an extended conversation in a cafe located right across the Montparnasse railway station a conversation that subse quently figured in his book on Rossellini's passage to India.The film director, hailed for his `neo-realist' films made in Italy in the wake of the Second World War, had arrived in Mumbai in December 1956 at the invitation of Jawaharlal Nehru to produce a series of documentaries as well as a feature-length film in four episodes that would showcase the country a decade after it won its independence from British rule.

Rossellini has first asked Francois Truffaut, then an enfant terrible among French film critics who went on to become one of the leading lights of the French New Wave Cinema, to work as his assistant in India. But Truffaut had other fish to fry. He therefore suggested the name of his friend Jean Herman, a dropout from the French Institute of Higher Cinematographic Institute and a lecturer in French literature at the Wilson College in Mumbai, as his replacement.

Herman had married a fellow student at the Institute, Lila, an Indian, done the French sub-titles of Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali and published articles on cinema in the Illustrated Weekly of India. This periodical, then a highly-valued brand of the Times of India Group, also carried the photographs he had shot during his travels across India.

No sooner had Rossellini offered him the post of assistant director than he resigned from his lecturer's job to follow, as he told me, in the footsteps of the new Messiah. The two walked the streets in Mumbai from dawn to dusk.Rossellini, Herman noted, was in thrall of the sights, sounds and smells of the city .The details that caught his attention would find their way in some form or the other in the scripts he dictated for the films: diversity of communities, clothes, headgears, languages, diversity of trades and professions, diversity of places of worship, diversity of musicians, hawkers, holy men and rituals.

Herman was present when Sonali, who agreed, at her husband's behest, to join the script sessions at the Taj. Rossellini seldom looked at her, Herman said, but there was not the slightest doubt that he sought to mesmerise her with his effusion of eloquence, intelligence and charm. He wanted her to be part of the shooting unit. When she refused, Herman said, he would send her one telegram after another. And when the telegrams went unanswered, he would chase her whether she was in Mumbai, Kolkata or Jamshedpur. Eventually , left to fend for herself by her husband and to face her angry and distraught relatives, she moved in with Rossellini.

Herman told me that for Rossellini India was much like Italy: a country in a permanent state of frenzy and delirium. Like the Italians, he believed, Indians were both emotional and highly pragmatic. Both belonged to the civilisation of `draped clothes' rather than to the civilisation of `stitched' ones.

Where did Sonali figure in all this? This is what Herman told me: “ Roberto always need to merge the vicissitudes of the cinema with the vicissitudes of his life. It was a romantic and liberating need.You can almost say which woman mattered to him in each of his films. It was no different in India.“

He added: “Roberto fell in love with Sonali instantly . To him she personified the nobil ity, beauty and intelligence of India. He was a compulsive talker. She, on the other hand, hardly said a word. Her silences were a mystery to him. And the only way he could unveil the mystery was t to seduce her.“

All of this the heat and dust of the scandal had been relegated to the past. What re mained, Herman told me, was the serenity and courage with which Sonali faced the hostility of the relatives and the yellow press and the way she adapted to her life in Italy. That was no easy task. As Sonali herself once confided to me: “ Ask me what it means to live with a genius.“ But Herman took what seems to me to be a lucid take on Rossellini's Indian in terlude: “ He had made up his mind that he would use his In dian experience to profoundly change his life, the way he shot his films and indeed his very ideas about the cinema.“ And . that is what he did in his subse quent documentaries: they de light but do not dazzle. The death of Jean Herman -alias Jean Vautrin brings to a close one of the most fasci nating footnotes in the history of cinema.