Sex Ratio: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Child sex ratio

Child sex ratio in nine states worsens

Rema Nagarajan TIG

In many of India’s least developed states, girls are disappearing not so much from foeticide as from infanticide or just plain neglect of the girl child leading to more number of girls dying. This is revealed in the latest Annual Health Survey data of the census office, which shows a substantial fall in the sex ratio in the 0-4 years age group in several districts spread across nine states. Since many of these are the most populous states, this fall would account for lakhs of missing girls.

In fact, in four of the nine states, it is not just specific districts but the entire state that has seen a worsening of the 0-4 sex ratio. What is also worrying about this trend is that most of these states have traditionally had better sex ratios than the national average. The malaise, it appears, is growing even where it wasn’t much in evidence in the past. In a majority of the districts in these states, the sex ratio at birth has actually improved.

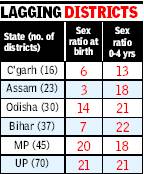

Child sex ratio: J’khand, Raj show maximum improvement

But about 84 of the 284 districts recorded a fall, even if in 31 of them the fall was marginal. The fall in sex ratio in the 0-4 age group is more widespread, with 127 districts exhibiting this trend,46 of them showing a significant drop. The census office has been conducting an annual health survey in nine states – Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand and Assam. A baseline survey conducted in 2007-09 has been followed up by similar ones in 2010 and 2011. Jharkhand, which had a relatively better sex ratio to begin with, and Rajasthan, which figured at the bottom of the pile, have shown the greatest improvement in both sex ratio at birth (SRB) and the 0-4 sex ratio.

States that started off with high sex ratio in both categories,such as Chhattisgarh and Assam, have recorded the biggest declines in 0-4 category along with Bihar and Odisha.

In UP, 30% of the districts recorded a fall in the 0-4 age group.In Chhattisgarh,the ratio fell in 13 out of 16 districts. As a result, the state’s 0-4 sex ratio fell from 978 to 965.

In Bihar, 21 of 37 districts registered a decline in 0-4 sex ratio.In Orissa,the0-4sex ratio declined in 21 outof 30districts. Uttarakhand had the worst sex ratio among these nine states to start with and despite showing some improvement, it continues to be the worst.

Sex ratio at birth (SRB):1999-2010

Born Unequal? '

The Times of India Oct 27 2014

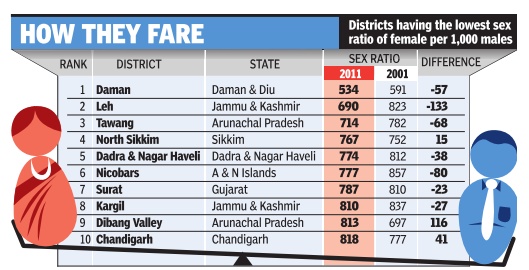

The child sex ratio (CSR), which is the number of girls aged 0 to 6 for every 1,000 boys of the same age, indicates the combined effect of extent of pre and post-birth gender discrimination. But it is the sex ratio at birth (SRB) that gives an indication of pre-birth discrimination or female feticide. The Census office has estimated SRB by back calculations from the actual observed population to arrive at what is called the implied SRB in the period 1999-2000 and 2004-10. It was found that half the states in the country, barring J&K, for which comparisons aren't available, have seen the ISRB drop by between 3 points and 33 points, Uttarakhand registering the worst decline.

2007- 2013: Some improvements

Jan 02 2015

More girls are being born, but fewer surviving

Subodh Varma

There is good news and bad news on one of the key problems that haunts India -survival of the girl child. Sex ratio at birth, that is, number of girls born for every 1,000 boys born, has inched up from 906 to 909 between 2007 and 2013. This suggests that female feticide, the monstrous practice of killing off the girl baby in the mothers' womb has been somewhat checked.That's the good news.

The bad news is that the child sex ratio, that is, number of girls in the 0-4 year age group for every 1,000 boys in the same age group, has declined from 914 to 909 in the same period.

Information on sex ratios is made available by the Census office based on their sample registration system (SRS) annual surveys over the years.

Experts and activists say that the slight increase in sex ratio at birth is not very significant though it is a welcome trend. They feel that laws prohibiting sex selection are not very effective.

“Perhaps, in cities, there is some prevention of sex selection due to laws but there is spread of this heinous practice in rural areas and in regions where earlier it was not there,“ argues Kirti Singh, lawyer and women's rights activist.

Ravinder Kaur, professor at IIT Delhi who has studied sex ratios and related family issues also said that laws and campaigns have not contrib uted much in controlling sex selection. “Sex determination services are still available for those who seek them. The change is due more to complex social changes happening including fertility decline, improvements in socio-eco nomic circumstances, etc.“

But the slight uptick in sex ratio at birth is negated by what happens to girls who are born and survive. Neglect, discrimination and in extreme cases even killing of very young girls is behind dipping child sex ratio. “There is a tendency to give the girl less food, or not treat her sickness with the same urgency as a boy's. There are many court cases on deaths of small girls.All this points to deep discrimination against girls,“ Kirti Singh said.

The increases and decreases are small at the country level but at the state level sharper trends are visible. Again, these are good and bad.

The good news is that Delhi, Haryana, Punjab and Rajasthan, which were the worst four states in terms of sex ratios both at birth and at the 0-4 age group, are the only states in the country where sex ratios at both levels are improving. Clearly , social outrage backed by better regulation has had some effect.In all four states, sex ratios are still below 900, pointing to the long road ahead.

But in six states -Assam, Jharkhand, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal -sex ratio both at birth and in the 0-4 age group are going down.

This is worrisome because these are states which had better sex ratios and now appear to be heading the way some of the north Indian states went earlier.

Apart from the six states above, sex ratio at birth has also declined in Andhra Pradesh (pre-division), Bihar, Chhattisgarh, and Himachal Pradesh. Child sex ratio has declined in Gujarat, Jammu & Kashmir, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh, besides the six states.

“There is no common explanation for the decline in some of the eastern and southern states; again a mix of fertility shifts, rise of son preference due to spread of dowry in some of these states etc. are decisive factors,“ Ravinder Kaur said.

Haryana: villages where girls outnumber boys

Rainwali does Haryana proud — 2,750 girls for 1,000 boys

Sukhbir Siwach,TNN | Aug 11, 2014 The Times of India

Rainwali

According to latest figures of the state health department, child sex ratio in the hamlet, Rainwali, is 2,750 girls against 1,000 boys, something unheard of in Haryana.

Haryana, known for its dubious distinction of having the worst child sex ratio in the country, has reasons to cheer about a small village in Fatehabad district.

According to latest figures of the state health department, child sex ratio in the hamlet, Rainwali, is 2,750 girls against 1,000 boys, something unheard of in Haryana. As per 2011 census, Haryana's child sex ratio was just 834 girls for 1,000 boys in 0-6 age group -- worst in the country.

Rainwali, located near Punjab border, has around 1,800 inhabitants, with a significant number of residents belonging to dalit backward classes.

Village sarpanch Gurkirat Singh, who is unaware of the development, gives credit to authorities for improvement in sex ratio. "No doctor here wants to take risk...They are very careful about the ultrasound tests also. They conduct ultrasound test only after getting the application counter-signed by village sarpanch," he said.

"We love our daughters like our sons," said Singh, who has won all elections for village sarpanch post since 1982, barring one.

Khan Mohammad

Another small village, Khan Mohammad, dominated by people of backward classes, has secured second place in the district where the child sex ratio is 2,000 girls for 1,000 boys.

They have formed special teams to check ultrasound centres to avoid sex determination," he added.

Top ten villages of Haryana

Name of Village/ Number of girls for 1000 boys

Rainwali (Fatehabad) -- 2750*

Khan Mohammad (Fatehabad) - 2000

Lotni (Kurukshetra) - 1909

Chuharpur (Yamunanagar) - 1818

Ajijpur Kalan (Yamunanagar)-1750

Samlehri (Ambala) - 1444

Muradpur Takena (Rohtak) -1428

Kot (Palwal) -1424

Dhos (Kaithal) - 1400

Baroli (Faridabad) - 1375

2011: Older mothers and the sex ratio

Mar 03 2015

Rema Nagarajan

Child sex selection seems to go up with the age of a mother, fresh data from Census 2011 shows. The sex ratio among children born to young mothers in the 15-19 age group was the highest, after which there was a steady decline till the 45-49 age group.This pattern held true across the country with no exception seen in any state, whether in rural or urban areas. The latest Census data on births that happened in the year preceding the survey showed that the ratio of number of girls to 1,000 boys, born to mothers in the 15-19 age group, was 938, way higher than the sex ratio of 899 for all children born during the year.

About 2.08 crore children were born in the year before the survey . The data showed that the sex ratio declined as the age of the mothers increased, falling from 927 and 897 in the 20-24 and the 25-29 age groups, respectively , to just 856 and 824 in the 40-44 and 45-49 age groups.

Since natural causes cannot explain this pattern, it appears this could be because, in the younger age group, where many of the children would be first-borns, there would be greater tolerance for girls. But, with advancing birth order and age of the mother, the pressure to produce a son would increase.

Interestingly, even in states with the best sex ratios, this pattern of a steep decline in the ratio with increasing age of the mother held true.

Salem: Tamil Nadu

India Today, June 15, 2015

Kavitha Muralidharan

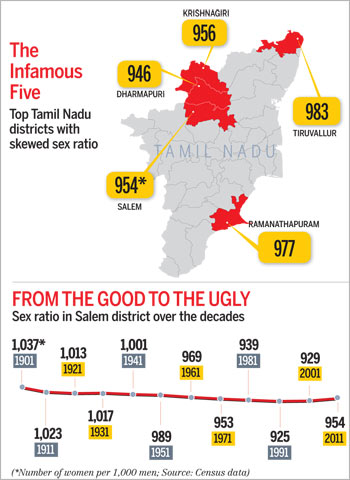

A major industrial zone, Salem is a Haryana inside Tamil Nadu with its skewed sex ratio. Pinning hopes on astrology for sex-selective abortions makes it stranger still.

A dilemma to choose between an unborn girl or boy that has become a part of life for a large percentage of women in Salem, the second worst district in the highly educated state of Tamil Nadu in terms of skewed sex ratio-954 women per 1,000 men as per the 2011 Census. Driven by a cultural preference for the male child, and anxiety over dowry and inheritance of family property in the case of daughters, there is an irony in this unwanted equality: sex-selective abortion cuts across caste, communities (practised by both the poor and the dominant communities of Gounders and Vanniyars, among others, lest their riches go to another household), and the rural-urban divide.

Although illegal diagnostic centres operate on the sly in state capital Chennai, or Dharmapuri-at 946 women per 1,000 men, the district with the worst sex ratio in Tamil Nadu- what makes Salem unique is the wide- spread use of astrology to identify sex.

In Salem, the astrological 'predictions' lead to many first-trimester abortions. In 2012-13, the district had reported more than 3,000 medically terminated pregnancies within 12 weeks of pregnancy, and more than 300 between 12 and 20 weeks. These are completely above board. What's not known is the number of illegal abortions that are done in the second trimester, or between the fourth and sixth month of pregnancy.

There has been no crackdown because astrology is extremely popular in the state, with many heavyweight politicians relying on it. It is also difficult to bring these 'astrologers' to book merely for making predictions.

Good and bad of clampdown

Shadowing the overall picture in the state, Salem has a markedly skewed child sex ratio of 917 girl children against every 1,000 boys in the 0-6 year age bracket compared to the overall sex ratio of 954, as per the 2011 Census-the respective figures for Tamil Nadu are 943 and 996. What this means is simple, and worrisome: the sex ratio will just get worse as these infants grow up. More so for Salem, Tamil Nadu's fifth most populous and a fast developing district, where the figure of 954 is certain to dip by the time the 917 infant girls grow up.

There's a bright tale even in this otherwise morose climate. According to Census figures, the child sex ratio in Salem is up from 851 in 2001. How did this come about? The answer is both simple and complicated. Until even a decade ago, Salem was notorious for infanticide. When an alarmed state government clamped down, people switched to foeticide, says V. Sumathi, who runs the NGO Green Foundation of India in Omalur, near Salem city.

So the clampdown addressed infanticide but energised foeticide. In 1992, J. Jayalalithaa, the then chief minister, announced the Cradle Baby Scheme. It was meant to tackle infanticide.

As part of the scheme, parents could drop unwanted babies-primarily girls-in cradles provided at government homes instead of killing them. Launched in Salem, the scheme was later extended to other districts. To a large extent, this initiative is believed to have helped the jump in child sex ratio in Salem in the decade to 2011.

A. Devaki, a child protection officer in Salem district, says more than 4,000 babies have been saved across the state under the Cradle Baby Scheme, nearly 3,600 of them girls. "Most of them are in school, many studying medicine and engineering," she says. Not that the scheme does not have critics. "How can the government encourage an initiative that allows people to abandon girl children?" asks Chennai-based activist Sheelu Francis. But Devaki has a defence to that: "Imagine, more than 4,000 children could have been killed but for our cradles."

As for the sex-determination tests done illegally, six centres found doing this were closed in Salem last year, say Health Department officials. "We strictly implement the PNDT Act, and give approval for (licence) renewal only when all conditions are met," says Joint Director of Health Services, Salem, N. Vijayalakshmi. But more than a dozen such centres are estimated to be still operating.

Tied in knots

The sex ratio may be getting healthier, albeit too gradually to make much impact, but the effects of the female infanticide and foeticide practised for at least three decades are showing. As a result, even men from the close-knit Gounder community, with a deep-rooted caste pride, have begun looking for brides outside the community-something that would have been frowned upon till recently. To stem the rot, Kongunadu Makkal Desia Katchi (KMDK), a caste-based party in western Tamil Nadu, has begun an awareness campaign. But it will take another decade for the efforts to pay off, admits E.R. Eswaran, KMDK general secretary. Devaraj exudes hope that the next generation of Gounder men can get married within the community.

For that, a bigger movement is required to change social mores. To not only amend the way the men think but to make someone such as Kalairani, from Kadayampatti, wipe out the feeling that it is an insult to give birth to a girl child.

Progressive Haryana Khaps

India Today, April 20, 2015

Asit Jolly

Haryana's patriarchal hinterland is witnessing the beginnings of a social transformation-the emergence of khap panchayats with a conscience that value women

A rapt audience of women-recently betrothed daughters, young housewives, mothers clutching infants, mothers-in-law, many grandmothers-nodding in unison as a young, recently commissioned woman police officer tells them why it is imperative to send girls to school; why they must resist any attempts to restrict women; why daughters and daughters-in-law must be honoured equally; why honour killings are a thing of the dark ages.

It's not an unusual setting, except that this is happening deep inside the intensely patriarchal Haryanvi hinterland.

The February 19 congregation in Bibipur village, 10 km along the highway from Jind to Bhiwani, was special in many ways. Besides the incredulously astute bunch of women, the menfolk were there too. Alongside Anita Kundu, a young woman from a landless, middle-class family of Uklana in Hisar who landed a job as sub-inspector in Haryana Police after she scaled Mount Everest in May 2012, Captain Mahavir Lohan, chief of Hisar's all-powerful Satrol khap-a caste council speaking for 44 villages-was there, equally vehement against the scourge of female foeticide and 'killing to preserve family honour'. On the day, the fringes of the quaint gathering at Bibipur's rather unique mahila choupal (women's village gathering) were crowded over with young and old members of the Nogama (nine villages) khap, each avidly voluntarily giving up his chair as more and more women walked in.

Located in the centre of Haryana's khapland, the events in Bibipur are significant and very possibly the earliest signs of what could potentially snowball into significant social transformation-khap panchayats with a conscience.

It started back on July 14, 2012 when Bibipur's young sarpanch Sunil Jaglan, 32, the proud father of two daughters, convened a mahapanchayat of 112 khaps representing rural communities across Haryana, Rajasthan, Western Uttar Pradesh and Delhi and inspired them to unanimously endorse a joint resolution demanding capital punishment for female foeticide.

"It wasn't easy," says Ritu, the sarpanch's 29-year-old sister recalling the "discomfiture" of the elders. "They were simply not used to women talking down to them," she recalls. "Jab mai bolne uthi to charcha ka vishey ban gaya (When I got up to address them, it became a topic of discussion)."

But not for long, Jaglan remembers the day: "Women participated without restraint, questioning senior khap leaders, for the first time, without fear." The unshakeable pradhans (leaders) capitulated. Years after the laws of the land proscribed sex-selection, khap elders unanimously concurred to demand that foeticide be equated with murder.

Jaglan says the khap leaders' willingness to endorse a resolution against the age-old preference for male progeny across Jat-predominant communities in northern India was driven by a growing awareness and heightening concern over dangerously skewed adult sex ratios that are set to become even sharper given highly distressing SRB (sex ratio at birth) being reported from scores of villages. Haryana for instance has an average statewide sex ratio of 879 women per 1000 men according to the 2011 Census. But there is a horrific story currently unfolding in the villages.

Data available with the state health department exposes the shocking truth and is perhaps why Prime Minister Narendra Modi chose to launch his flagship 'Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao' campaign from Haryana on January 24, when he fervently exhorted its people "not to kill daughters".

More than half-3,974 out of 7,363 -of the villages in the state reported an SRB (0 to 1 year) below 500 in 2013. These include Gajarpur in Mewat district, Kharal in Jind, Bopur in Kaithal and Suri village in Panchkula where the ratio stood abysmally low between 76 and 143 females per 1000 male births. There are some 2,400 villages including a few small hamlets that failed to report the birth of even a single girl child in 2013.

Ram Niwas, Haryana's additional chief secretary in charge of the state health department, says increasingly skewed sex ratios reflect the hard truth and can no longer be wished away. "It is true. More and more girls are being killed in the womb," he says, warning that the situation, already critical, could in time result in a "virtual collapse of rural Haryanvi society".

Niwas points to the presence of scores of bachelors simply unable to find brides in almost every village. The telling dearth of women consequent to the prevalent practice of foeticide, younger members of the Nogama and Satrol khaps say, becomes even more acute with the gotra or kinship codes enforced strictly by most khap panchayats. According to him the landmark 2005 amendment to the Hindu Succession Act giving daughters an equal share as sons in the inheritance of ancestral property and the consequent familial disputes have only refuelled the preference for male children.

Anil Kumar and Suneel Lamba, young farmers in their mid-20s from Jind, don't see themselves settling down anytime soon. They say "it is almost as difficult finding a bride as it is getting a government job in Haryana". Both men actively participate in khap meetings with the singular aim of nudging more tradition-bound elders into slackening restrictions on marital alliances.

Evidently alive to the problem and encouraged by younger members to ring in change, on April 20, 2014, the Satrol khap voted unanimously to reverse a 650-year-old tradition. For the first time in centuries, the khap leaders proclaimed that they would endorse and support inter-village marriages as well as weddings between castes.

Jaglan, who attended the Satrol panchayat in Hisar as a special invitee, sees the decision as "historic and revolutionary". Significantly, the sarpanch says, "they (leaders of the Satrol khap) also decided to recognise love marriages." According to Lohan, the khap now offers a cash incentive of Rs 21,000 for every inter-caste marriage solemnised within its area. Also responding to long-standing criticism, women are now actively encouraged to participate and speak in khap meetings.

Interestingly, khap leaders are employing historical precedent to demolish what has been viewed as inviolable tradition: Lohan cites an early 1960s instance when Ghasiram Malik, then head of the Malik clan, publicly blessed a marriage between a couple sharing the same gotra. He recalls how the old khap chief had proclaimed that the couple's child would be an "asli Malik". Lohan also narrates a past instance when an old Zaildar of the Satrol khap had openly questioned the practice of marrying daughters in barren and un-irrigated areas outside the highly fertile 44-village collective.

Just weeks after the Satrol khap announced its changes last April, Bhiwani's most prominent Sangwan khap too proclaimed it would bless both inter-caste as well as inter-religion marriages.

But many activists and scholars remain sceptical. D.R. Chaudhry, formerly a teacher at Delhi University, says the changes are "cosmetic and driven essentially by the compulsion of circumstances". "Inka dimaag their basic-anti-lower caste and misogynistic-mindset is unchanged," he says. Even if a trifle grudgingly, Chaudhry however acknowledges the efforts by Jaglan and his colleagues in Bibipur.

Besides the role he played in instigating change in Satrol and other khaps, Sunil Jaglan, who was elected sarpanch of Bibipur in June 2010, has single-mindedly pursued an agenda to include the womenfolk of his village. His move to involve the khaps and get them to endorse a resolution against female foeticide in July 2012 may not have paid off significantly in inspiring wider relaxations on questions of inter-caste and inter-gotra marriages but it is a vital beginning.

At the rural congregation on February 19, incidentally the 50th such event since January 24, 2012, Bibipur's womenfolk were decidedly more vocal than the men. Santosh Devi, whose only estimate of her own age is the memory that she "was already bearing children when Pakistan was formed", cheered the loudest when Jaiwanti Sheokand, one of the speakers and a former IAS officer, declared that "a girl can never go 'bad' by going to school and reading books".

Bibipur's women, many of them casting off the traditional ghunghat (veil), were happily at home with sub-inspector Anita Kundu in her hip-hugging jeans, sneakers and closely cropped hair. "I wish I too had a daughter like you," a woman said to her. Kundu smiled and told her: "Your girl will be exactly like me, just make sure she goes to school."

Statistics on women's education in Haryana are almost as damning as the data on missing girl children. Jaglan says "barely 20 per cent of the school-going girls make it to colleges simply because their parents fear they will be sexually targeted going to or coming back from institutions that are invariably some distance away in cities". The panchayat is currently campaigning hard for the state government to provide 'secure last-mile connectivity' for rural girl students.

In 2014, the Bibipur panchayat adopted a formal resolution giving women complete control over 50 per cent of all cash awards and one-time grants to the village. Jaglan and his friends (the village women included) hope that progressively more and more khap leaders will pay heed and break with dubious traditions.

In the meantime though, this happy hamlet is swimming against the tide in celebrating its women: a gate at the entrance to the village makes a point of welcoming visitors to "Bibipur-the Women's World".