Dilip Kumar: a biography

August 2017: This page is being expanded regularly and will keep getting expanded till it reaches the end of Dilip Kumar's career and autobiography. You can keep coming back for more after every few days

If you wish to contribute photographs and/ or biographical details about Dilip Kumar (or any other subject), please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name. |

Profile

Dilip Kumar was born on December 11, 1922 in the city of Peshawar in present-day Pakistan. His childhood name was Mohammad Yousuf Khan (Muhammad Yusuf Khan). His father, Lala Ghulam Sarwar used to sell fruit to feed his family.

Early life

His family migrated to Bombay during the Partition of India. He passed his early life in difficult conditions. The losses in the trade of his father made Dilip work in a canteen in Pune. That was where Devika Rani first sighted him, and it was from there that she made an actor of Dilip Kumar. Dilip Kumar was the new name that he assumed.

Bhojpuri As a youngster, he spent many years in the hill town of Deolali in Maharashtra. Once, squatting in the kitchen of their gardener he heard a dialect of Hindi which, he says, fascinated him. This was Bhojpuri, though he didn't know that at the time. "It sounded fascinating and there was a vivid expressiveness about it while conveying raw emotions," he recalls. His Gunga Jumna is noted for its authentic use of Bhojpuri and the actor says the film came from his long ambition to work the magic of the dialect into a story on screen.

In 1947, when he was twenty-five years old, Dilip Kumar was the star of what, according to most sources, was the no.1 hit of the year. He tasted superstardom as early as that. His position at the top was cemented the next year. He was rapidly accepted as the country's number one actor.

Dilip Kumar’s autobiography: excerpts

Excerpted from Dilip Kumar | The Substance and the Shadow, an autobiography |As narrated to Udayatara Nayar |©2014 Dilip Kumar | Hay House Publishers

Childhood in Peshawar

[On the day of the] grand arrival of the fourth child of Mohammad Sarwar Khan and Ayesha Bibi [a] blizzard was raging outside and, what was worse, the Goldsmiths’ Lane was in flames, blocking normal transport. 11 December 1922. I suspect the date is mentioned somewhere in some chronicle of Peshawar’s history not because I was born on that dramatic day but because fire had gutted the gold- smiths’ workshops.

One ordinary day, when I was playing in the front room of our house, a fakir came to the door seeking food and some money.He fixed his stare on my face and told Dadi: ‘This child is made for great fame and unparalleled achievements. Take good care of the boy, protect him from the world’s evil eye, he will be handsome even in old age if you protect him and keep him untouched by the evil eye. Disfigure him with black soot if you must because if you don’t you may lose him prematurely. The Noor [light] of Allah will light up his face always.’

Dadi took it upon herself to protect me from the evil eye of the world. She had my head shaven and every day, when I started for school, she made a streak on my forehead with soot to make me look ugly. Amma tried hard to convince her not to make her child so ugly that other children would poke fun and give him a complex.

Aghaji [as Dilip Kumar called his father] tried to reason with his stubborn mother about the consequences of what she was doing to me. But Dadi wouldn’t budge. Her love and protectiveness towards me were too overwhelming for her to accept their pleadings.

Needless to say, I was a spectacle when I arrived in the school every morning. The murmurs and sniggers that greeted me on the first day amplified in my subconscious and made me find reasons not to go to school the next day. I gave vent to my unhappiness and narrated the derision I faced from my classmates and older boys of the school who were always ready to seize occasions to have fun at the expense of any junior who was easy prey to their pranks and jokes. It was the pain I endured as the alienated child in school that surfaced from my subconscious when I was playing the early tragic roles in my career and I had to express the deep mental agony of those characters.

Yet another pastime I indulged in solitude was imitating the ladies and men who came visiting my parents. Amma caught me at it one day and chided me gently, saying it was not good to make fun of elders. I was mimicking Khala [aunt] Mariam when she came in unexpectedly and saw what I was up to. I did not tell Amma that I was not making fun of Khala Mariam but I was trying to be Khala Mariam for a few moments because she was such an intriguing character.

Aghaji [DK's father] had many Hindu friends and one of them was Basheshwarnathji, who held an important job in the civil services. His elder son came to our house with him a few times and he stunned the ladies with his handsome appearance. That was Raj Kapoor’s father Prithviraj Kapoor. Basheshwarnathji was very friendly with Aghaji and I often heard them discuss an impending war (the Second World War) and what was in store for the inhabitants of Peshawar.I listened to their talk intently but I could not fathom what they were talking about. They were talking about a city called Bombay where business opportunities were many. Then one day I heard Aghaji tell Dada that he was going to Bombay to explore such opportunities and he intended to go alone first. The war was inevitable and it was bound to impact the fruit business as transportation of marketable produce from the orchards in Peshawar to markets elsewhere would become difficult. Before I knew it he was off to Bombay one morning.

The mid-1930s: The family shifts to Bombay

Though Dadi didn’t quite agree with her son’s move to shift the family to Bombay, for once Dada stood firm on his decision to give his daughter-in-law the right to live with her husband.

I think it was some time in the mid-1930s. The apartment rented out by Aghaji was in a four-storeyed structure called Abdullah Building on Nagdevi Street, near the bustling Crawford Market, where he had set up his fruit business on a wholesale basis at first.Aghaji seemed satisfied with his fruit business, which was prospering. He didn’t have to go to the fruit stall at Crawford Market every day as he had employed men to receive the consignments and deliver them at the market besides managing the daily sales.

In Bombay I was enrolled at the Anjuman Islam High School and there was no more shaving of my pate. I now wore my skull cap over a thick growth of black hair, which elicited compliments from all the ladies who visited Amma.

Deolali

As [DK’s brother] Ayub Sahab grew up, he developed a respiratory disorder, which necessitated our moving to Deolali (a hill station in Maharashtra, located about 180 km from Bombay). The fresh air in Deolali and the availability of medical care there made it the ideal location for his treatment and recovery.

Being an army station, Deolali had good educational institutions, and one of them was Barnes School where I was admitted.Deolali is of significance in my life in more than one respect. First, it was at Deolali that I learned the English language and became quite proficient in it. Secondly, it was during our stay in Deolali that I began to take keen interest in soccer.

There was an English poem that I learned in school, which I recited before Aghaji one day and he was so happy that he made me recite it before all his distinguished English-speaking friends. Each time I completed the recitation there would be encores. There would be cries of ‘shabash [well done] Yousuf’. Each time I had to start all over again. The encores came again and I would straighten myself, take a deep breath and begin reciting the same poem once again.

I think Destiny had already begun to chart out the life I had to lead.I think I was stimulated to perform by the applause and encores I received. It was as if I could see a door, a wall and a ceiling when I recited. I had my first brush with the make-believe world into which I was to make my fateful entry years later.

At Deolali, Ayub Sahab had no option but to spend his waking hours reading whatever Urdu literature he could lay his hands on. He always liked to read the latest novels and he devoured newspaper articles and short stories with great delight. To make him happy, as I grew up and progressed in my study of English, I read the short stories (in translation) of the nineteenth-century French writer, Guy de Maupassant, and narrated them to him. That was my first introduction to published literature from abroad and I was fascinated by the plot structure and storytelling ability of the author. In a latent sort of way, I was developing a keen narrative skill by reading the works of English and other European authors that I found in the library of Barnes School.

The climate was perfect and we had flowers and fruits in the trees in our garden, which was tended to by a jovial maali and his wife who spoke a UP (then known as United Provinces and later called Uttar Pradesh) dialect, which fascinated me. Many years later, when I began to work on the dialogues of the film Gunga Jumna (released in 1961), it was this dialect that came to my mind and ears repeatedly.

Deolali, as a picturesque place, figured prominently in my imagination when we got down to de- tailing locations in the screenplay of Gunga Jumna. The hills, the plains and the thick groves made up of all varieties of woodland trees lining the banks of the winding streams, sprang up before my eyes when I pictured the locations for Gunga Jumna in my mind. In retrospect, I feel Deolali provided as much impetus to my creative thoughts when I sketched the rugged setting of Gunga Jumna’s core conflicts and dramatic scenes. I am inclined to subscribe to the belief that childhood images cling to the subconscious surreptitiously Poona gave me a sense of self-assurance and the initial opportunity to develop my character.

When the doctors felt Ayub Sahab was doing better, Aghaji shifted us back to BombayIt was not just for my education that Aghaji had to find resources. All my younger brothers and sisters had to be educated as well. The recession was setting in as I began attending high school and then Khalsa College at Matunga (a locality in central Bombay). For some reason Aghaji had great dreams for me. He wanted me to pursue my education and acquire impressive degrees.I overheard him chiding my Amma once. ‘He should not be selling fruits. He should be studying law. He must go abroad and study there. He has the potential to become somebody.’

Friendship with Raj Kapoor

I was shy and reserved by nature but I made friends easily with select college mates. At the Khalsa College I met Raj Kapoor after years. Raj’s grandfather, Dewan Basheshwarnath Kapoor, used to visit us in Peshawar. The joy of speaking the same language, Pushtu, was itself something special for the two families.I envied Raj Raj was always at ease with the girls in the college and his extrovert nature and natural charm earned him considerable popularity. If there was anything impressive about me at that stage, it was my performance in sports and my acquaintance with English and Urdu literature.

On the field, while playing football or hockey, I was completely at ease and focused to the point of forgetting everything else.Raj Kapoor became a close pal and he used to take me to his house in Matunga where his father Prithvirajji and his demure wife kept the doors of the house open all the time I felt completely relaxed with Raj’s family. The liberal and infectiously friendly Kapoors had no hesitation whatsoever in sharing their heartiness with whoever was willing to absorb it.Raj’s younger brothers, Shammi and Shashi, were in school then. Raj had only that much interest in soccer as most others in the college. The majority of my college friends were interested in cricket and Raj, too, was more a keen cricket player than a soccer playerI remember an occasion when Raj tested my guts by telling me that a beautiful girl studying in the college wanted to be introduced to me and he pointed to one standing some distance away. He urged me to go and speak to her. There were quite a few boys and girls around us and Raj kept on urging me to walk up to her. I was extremely embarrassed and I told him I could not do that with so many eyes staring at me. He then said: ‘Okay, let us go to the canteen.’ He signalled to the girl to come to the canteen and, to my dismay, she was right there at the table that Raj was leading me to. I had to speak to her and I think she realized she would be wasting her time if she chose me to be her friend. She just got up and left after a few minutes.

Raj was determined to rid me of my shyness. One evening he came over to my house and insisted on going to Colaba for a walk on the promenade opposite the Taj Mahal Hotel. I readily agreed. When we alighted from the bus near the Gateway of India, he said: ‘Let us take a tonga ride.’ I agreed. We boarded a tonga and just when the tongawala was about to prod the horse to get going, Raj stopped him. He noticed two Parsi girls standing on the footpath. They were wearing short frocks and giggling about something. Raj craned his neck and addressed them in the Gujarati that the Parsis speak. The girls turned to him. Very chivalrously and politely he asked them if he could drop them somewhere.

They must have thought he was a Parsi, his fair complexion and good looks being such. They said they would appreciate a lift to the nearby Radio Club. He asked them to hop in. I was holding my breath in suspense not knowing what he was up to. The two girls got in and one of them sat next to Raj while the other sat next to me in the opposite seat. I made ample space for the girl to sit comfortably while Raj did nothing of the sort. He had the girl sitting very close to him and, after a minute, they were talking like long-lost friends. Raj had his hand around the girl’s shoulder and she was not in the least bothered. While I began to squirm with embarrassment, Raj was chatting away merrily.

They alighted at the Radio Club and I heaved a sigh of relief. It was Raj’s way of getting me to feel relaxed in the company of women. As Prithvirajji’s son he had an aura around him and was popular in the college campus. He knew he was heading for a profession in which there was no room for reticence or shyness. I did not have a clue about what was in store for me. All I wanted then was to become the country’s best soccer player.

The Poona interlude

The Second World War was raging and the family was going through a crisis caused by diminishing income from the fruit business, which was becoming difficult to maintain as the supply from the North West Frontier had dwindled due to strict wartime curbs on trade and transport of non-essential com- modities.I wished to be of some help to Aghaji by generating substantial income but I had no idea how I could do so.I could see that Aghaji was carrying the burden of an uncertain future in his mind and I should have not behaved the way I did on that morning. I left home with just forty rupees in my pocket, boarding a train to Poona from Bori Bunder station. I found myself seated amidst all sorts of men and women in a crowded third-class compartment. I had never before travelled third class and I hoped no one known to Aghaji had seen me at the railway terminal boarding that compartment because he was always one to give his sons the best in everything and all of us had first-class passes for our local travel.I was determined to prove to Aghaji that I could survive away from the se- curity of our home and the easy life he had provided us with. In Poona, I went first to an Iranian café, where I ordered tea and crisp khari (salty) biscuits.I spoke to the Iranian owner of the café in Persian, which made him very happy. I gingerly asked him if he knew anybody who wanted a shop assistant or something. He told me to go to a restaurant that was not far from his café and meet the owners, an Anglo-Indian couple.

It was my habit to walk briskly, so I reached the restaurant in no time. It was a quaint restaurant with its doors open for people who came there regularly, I guessed, for a good English breakfast.I spotted the couple having an animated conversation at the cash counter.I quickly introduced myself without revealing much. I referred to the Iranian café owner who had directed me to them. The lady was plump and matronly. She smiled hesitatingly through the dimples in her freckled cheeks and nudged her tall sturdy husband saying: ‘The boy speaks good English. Send him to the canteen contractor.’

Mr Welsely, as I understood his name was, looked at me carefully, paying scant attention to his wife’s recommendation, and asked me if I hailed from the North West Frontier Province. When I mur- mured in the affirmative, he told me that he knew the army canteen contractor who was a native of Peshawar and had settled down in Poona and was a much respected person. This was something I was dreading. Anyone from Peshawar would know Aghaji and that would lead to trouble for me as the news would reach him about my job hunting in Poona. Brushing aside all the wild thoughts crowding my mind, I told Mr Welsely I would be grateful if he could put in a word for me. He agreed and the next thing on my agenda was to find a place to stay, a room may be in a hotel that could give me decent comforts like a clean bed and a bathroom with hot water. I asked Mr Welsely if he could suggest such a hotel. He sent me to one that had the amenities I had mentioned.

The canteen contractor Taj Mohammad Khan had the usual awe-inspiring bearing of a Pathan and he did not ask me any questions. He gave me a sheet of paper and a pen and dictated a letter to the canteen manager request- ing him to employ me as his assistant. I took the dictation obediently and corrected the English, which betrayed his not having much familiarity with the language. He was impressed but he did not want to show it to a rank outsider, I surmised.

There was no talk of wages but I presumed it would be decent and suffi- cient to sustain myself. My job entailed several responsibilities bundled together under the head: general management.There was something fishy going on between the vendors and the manager about which I came to know by and by when I rejected some of the stuff that was of lesser quality but was being purchased at a higher price. The beer in the barrels was being mixed with buck- ets of ice and cold water to augment the quantity and I brought the matter to the manager’s attention dutifully. He advised me to overlook itI think he appreciated my feigned ignorance of his doings and, in return, he was extremely nice to me.I was extremely conscious of my hairy body, especially the hair on my hands, which would fall limp on one side when water fell over them and so would all the hair on the rest of my body. Hence, I never liked the idea of exposing my body. It is for this very reason that I have had a preference for long-sleeved shirts.

So in all fairness to the aesthetic senses of whoever might set eyes on my ape-like ap- pearance in a swimming pool, I had sensibly decided not to ever descend into one. An idea occurred to me one day when the regular chef was absent and the manager asked me if I could come up with something as a major general was having a few important guests for tea. I told him I could make sandwiches with reasonable success.Fortunately, the sandwiches were a hit. The guests of the major general praised the manager, who received the compliments smiling broadly. That was when the idea occurred to me to request him to get sanction from the contractor and the club’s office bearers to let me set up a sandwich counter at the club in the evenings.

My sandwich business opened very successfully. All the sandwiches were sold out in no timeOn the second day, I brought out a large table and covered it with white, starched cloth and laid out fresh fruits that I had selected carefully from the market along with sandwiches and chilled lemonade. The second day was a bigger success and, in less than a week’s time, I was counting the rewards When I began making money from the sandwich business, I found the courage to send a telegram to my brother Ayub Sahab informing him that I was in Poona and he may please tell Amma that ‘I am well and working in the British Army canteen’.

My telegram must have given Amma much relief.

Jailed for nationalistic views

It was wartime and there used to be discussions among the senior officers about India’s neutral stand in the war. One evening an officer asked me to give my opinion on this topic and as to why we were fighting for independence from British rule so relentlessly while we chose to stay unaligned in the war. I gave him what I thought was a good reply and he asked me if I would make a speech before the club members the next evening when the attendance would be full. I agreed and spent the night preparing my speech. I had studied the British Constitution as a student at Anjuman Islam School and put that knowledge to good use in preparing a speech that outlined our superiority as a nation of hard-working, truthful and non-violent people.

While making my speech in the club, I emphasized that our struggle for freedom was a legitimate one and it was they, the British administrators, who were consciously misrepresenting the civil laws of their Constitution and creating the consequences.

My speech evoked genuine applause and I felt elated but the enjoyment of my success was short- lived. To my surprise, a bunch of police officers arrived on the scene and handcuffed me, saying I had to be arrested for my anti-British views. I was taken away to the Yerawada Jail and locked up in a cell with some very decent-looking men, who I was told, were satyagrahis (followers of Mahatma Gandhi who offered passive resistance). On my arrival, the jailor referred to me as a ‘Gandhiwala’

In the morning, the major had come to release me and take me back. He was a good chap with whom I had played badminton when I could find time

Back to Bombay

AS THE WAR SITUATION WORSENED, SOME INEVITABLE CHANGES occurred. The office bearers of the club changed and the contractor, Taj Mohammad Khan, was replace dBy that time, I had earned a bundle of currency notes, which I counted for the first time. I had a good five thou- sand rupees, which was a great deal of money those days. I thought it was time to return to Bombay and seek a job that Aghaji would approve of or assist him in the running of the fruit business.

I was also toying with the idea of taking up a completely new line of business: feather pillows. I had made contact with a man who was ready to make me a partner and give me a substantial commission for selling such pillows to the gentry. I accepted his offer and deposited the earnest money.

After losing some money, I found out soon enough that the business of selling pillows wasn’t up my alley

Aghaji was talking to me about an apple orchard in Nainital that was on sale. He wanted me to go there and see if I could negotiate and close the deal I went there and met the owner of the orchard, a kind man who respected Aghaji and was keen to sell his land and trees to us. I could see that more than half the orchard had been destroyed by locusts and what remained was hardly worth buying. I told him we would have to negotiate the price. He said: ‘Of course, I understand.’ I had no idea what price to quote and sensing my inexperience in the business, he told me: ‘Son, I will take a rupee from you as token and we will close the deal. After you go back Khan Sahab can offer me whatever he deems good for the property.’ I returned home with the rupee and told Aghaji about the property. He was very pleased.

1942: How DK became an actor

THE TURNING POINT

ONE MORNING, I WAS WAITING AT THE CHURCHGATE STATION from where I was to take a local train to Dadar (in central Bombay) to meet somebody who had a business offer to make to me. It had something to do with wooden cots to be supplied to army cantonments. There, I spotted Dr Masani, a psychologist who had once come to Wilson College, where I had been a student for a year. Dr Masani had then given a lecture on vocational choices for arts students. At Churchgate, I went up to him and introduced myself.

He knew me well since he was one of Aghaji’s acquaintances. ‘What are you doing here Yousuf?’ he asked me. I told him I was in search of a job but since there was none in sight, I was trying to do some business. He said he was going to Malad (in the western suburbs) to meet the owners of Bombay Talkies (a movie studio) and it would not be a bad idea if I went with him and met them. ‘They may have a job for you,’ he mentioned casually. I pondered for an instant and then I joined him, giving up the idea of going to Dadar.

Though Bombay Talkies was not very far from the Malad station, he, nevertheless, took a cab to the studio since it was almost lunchtime and he was afraid that Mrs Devika Rani, the boss of Bombay Talkies, may go home for lunch. When Dr Masani entered [the office], there was warm recognition from Devika Rani who offered him a seat and looked at me wonderingly while I waited to be introduced. She was a picture of elegance, and, when Dr Masani introduced me, she greeted me with a namaste and asked me to pull up a chair and be seated, her gaze fixed on me as if she had a thought running in her mind about me. She introduced us to Amiya Chakraborthy (a famous director, as I later came to know), who was seated on a sofa. She asked me if I had sufficient knowledge of Urdu. I replied in the affirmative

She turned to me and, with a beautiful smile, asked me the question that was to change the course of my life completely and unexpectedly. She asked me whether I would become an actor and accept employment by the studio for a monthly salary of Rs 1250.So I returned her charming smile and told her that it was indeed kind of her to consider me for the job of an actor but I had no experience and knew nothing about the art. What’s more, I had seen only one film, which was a war documentary screened for the army personnel in Deolali.On reaching home I told Ayub Sahab about the offer. He found it hard to believe that Devika Rani had offered me Rs 1250 per month. He said it must be the amount she would pay annually. He said he knew that Raj Kapoor was getting a monthly salary of Rs 170. I felt Ayub was right.

The year was 1942 the prospect of earning the four-digit figure, had drawn me to a profession I knew my father had little respect for. On more than one occasion I had heard him tell Raj Kapoor’s grandfather, Dewan Basheshwarnath Kapoor, jokingly that it was a pity his son and grandsons couldn’t find anything other than nautanki as their profession.

The next day Devika Rani welcomed me and took me personally to the floor where preparation for a shoot- ing was going on. She led me up to a man who was very well dressed and looked distinguished. He looked familiar and I recalled having seen the handsome countenance on posters and hoardings near Crawford Market. His dark hair was combed back and he smiled through his eyes at me. Devika Rani introduced me, saying I had just joined as an actor. He held my hand in a warm handshake that marked the beginning of a friendship that was to last an entire lifetime between us. He was Ashok Kumar, who soon became Ashok Bhaiyya (brother) to me.Raj Kapoorwas justly shocked to see me there.‘Does your father know?’ he asked me mischievously.

I did not reply because both Ashok Bhaiyya and Devika Rani were standing by our side and they were pleasantly surprised to learn that Raj and I knew each other. Raj gave a short account of our football days at Khalsa CollegeRaj was talking con- tenuously I thought he would give away the secret that I had joined the studio without Aghaji’s knowledge.

There was no doubt that Raj was happy to see me and welcome me into the profession.

Learning the ropes

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION!

For the first two months, Devika Rani made sure that I was present at all the shootings. Ashok Bhaiyya soon introduced me to (producer) Shashadhar Mukherjee Sahab(popularly known as S. Mukherjee), who was his brother-in-law. When he saw me, he came up to me and began talking informally as if we had known each other for years. He said he knew why I was there. ‘It is all very simple,’ he continued, as he walked with me to the door and stepped into the open area outside the studio floor. He called for chairs and the studio hands came hurriedly to attend to him.

He went on: ‘You are a handsome man and I can see that you are eager to learn. It’s very simple. You just do what you would do in the situation if you were really in it. If you act it will be acting and it will look very silly.’

There was genuine warmth in his laughter and his words gradually began to make sense to me.It was a period of transition for Bom- bay Talkies as Devika Rani, who had been managing the studio after the death of her husband and co-founder of the studio, Himanshu Rai (on 16 May 1940), was planning to marry the famous Soviet painter Svetoslav Roerich and leave the management of the studio in the hands of S. Mukherjee Sahab and Amiya Chakraborthy.

S. Mukherjee Sahab said he wanted me to meet all the writers, especially those from Bengal. ‘I want you to be there at all our story meetings and be a part of our writing teams. You have the grasp of the language that is wanting in our Bengali writers,’ he pointed out.

I thought it would be awkward for me to be participating in the discussions pertaining to the dia- logues for the stories written by such eminent directors as Amiya Chakraborthy and Gyan Mukherjee.

However, it wasn’t so. At least S. Mukherjee Sahab had made it both easy and friendly for them and me in his own genial way. My regular witnessing of shootings and my interactions with Ashok Bhaiyya were prepar- ing me for my debut. I had begun to observe Ashok Bhaiyya closely when he would be rehearsing or facing the camera. I noticed that he had made calculated movements before the camera, which he had worked out all by himself. When I got a chance to speak to S. Mukherjee Sahab alone, I mentioned my observation to him and he suggested that I go and view as many feature films as I could so that I could observe how different actors attained their levels of competence before the camera in rendering long-winded and difficult scenes.it was difficult to go straight from the studio to a cinema theatre and watch a film and go home late in the night. Besides, if someone saw me going to a theatre and reported it to Aghaji, it would raise questions in his mind because he knew I had no interest in the amusement offered by films

How Yousuf Khan became Dilip Kumar

One morning, as I entered the studio I was given the message that Devika Rani wanted to see me in her office.. She said, quite matter-of-factly: ‘Yousuf, I was thinking about your launch soon as an actor and I felt it would not be a bad idea if you adopted a screen name. You know, a name you would be known by and which will be very appropriate for your audience to relate to and one that will be in tune with the romantic image you are bound to acquire through your screen presence. I thought Dilip Kumar was a nice name. It just popped up in my mind when I was thinking about a suitable name for you. How does it sound to you?’

I was speechless for a moment, being totally unprepared for the new identity she was proposing to me. I said it sounded nice but asked her whether it was really necessary. She gave her sweet smile and told me that it would be prudent to do soWith her customary authority, she went on to tell me that she foresaw a long and successful career for me in films and it made good sense to have a screen identity that would stand up by itself and have a secular appeal.

S. Mukherjee Sahab noticed that I was rather contemplative that afternoon as we ordered lunch he asked me if there was something disturbing me and if I could share with him. I told S. Mukherjee Sahab about the suggestion that had come from Devika Rani. He reflected for a second and, looking me straight in the eye, said: ‘I think she has a point. It will be in your interest to take the name she has suggested for the screen. It is a very nice name, though I will always know you by the name Yousuf like all your brothers and sisters and your parents.’

(I later came to know that Ashok Kumar was the screen name of Kumudlal Kunjilal Ganguly.)

I was touched and it was a validation that cleared my thoughts then and there. I decided not to speak about the new name to anyone, not even to Ayub Sahab.

1944: DK’s first film

Ashok Bhaiyya was a superstar now and he was delighted that I was going to be launched with a film titled Jwar Bhata to be directed by Amiya Chakraborthy.

A strange truth was that I was not even slightly nervous or excited about the fact that I was going to face the camera for the first time when the D-day arrived for my first shot. I was given a simple pant and shirt to wearDevika Raniwas a great expert in make-up and knew what exactly suited the lighting of the set and the nature of the scene to be shot. She checked the light strokes of make-up given to me and asked where the camera would be placed.

She was quite satisfied with everything except my bushy eyebrows. She asked me to sit down on a chair and she called for tweezers from the make-up man and very deftly pulled off some unruly growth of straggling hair from my eyebrows to give them a proper shape while I held my breath and endured the pain it was causing. She smiled when she saw the tears brimming in my eyes as a result of the tweezing and very jovially suggested that I take a look at my face while the make-up man quickly applied some cream to ease the painful sensations on my poor eyebrows. She left after wishing me luck.

My first shot was explained to me by Amiya Chakraborthy. He made a mark on the ground and told me: ‘You will take your position here and you will run when I say “ACTION”. I will first say “START CAMERA” but that is not for you. “ACTION” is for you to start running and you will stop running when I say “CUT”.’ I asked him very politely if I may know why I was running. He replied I was run- ning to save the life of the heroine who was going to commit suicide.It was an outdoor scene and the camera was somewhere in the distance.I had been an athlete at college consistently winning 200-metre races

The shot was ready and the minute I heard ‘ACTION’, I took off like lightning and I heard the dir- ector scream: ‘CUT, CUT, CUT.’I saw him gesticulating and trying to tell me something I couldn’t figure out. I stood rooted to the spot I had reached in a flash and Amiya Chakraborthy ambled over, looking highly displeased. He told me that I ran so fast that it was a blur that the camera had captured.

It was a bit perplexing for me when he told me at first to slow my pace because I thought it was important for me to run as fast as I could and save the girl who was going to end her life. However, when Amiya Chakraborthy explained the action as something that should register on the film in the camera, which would move at a particular pace, I understood in no uncertain terms that I faced a big challenge and the business of acting was anything but simple. The shot was okayed after three or four calls for ‘CUT’.

I am often asked what I thought of my first performance and my first film, which was released in 1944.

Honestly, the whole experience passed by without much impact on me.To express love to someone completely unknown and unattached to one in reality was, at that age and time, a tough demand. I think Amiya Chakraborthy understood my predicament but he was persuasive enough to get a reasonably good output from me in the romantic scenes. When I saw myself on the screen, I asked myself: ‘Is this how I am going to perform in the films that may follow if the studio wishes to continue my services?!’ My response was: ‘No.’ I realized that this was a difficult job and, if I had to continue, I would have to find my own way of doing it. And the critical question was: HOW?

New aspirations, new experiences

I BEGAN TO VIEW MOVIES REGULARLY, BRAVING THE POSSIBILITY of being caught by someone known to my family. I must confess that the new identity as Dilip Kumar had a liberating impact on me. I told myself Yousuf had no need to see or study films but Dilip surely needed to accumulate observations of how actors reproduced the emotions, speech and behaviour of fictitious characters in front of a camera.I started getting the hang of it as I watched Hollywood actors and actresses like James Stewart, Paul Muni, Ingrid Bergman and Clark Gable but it did not take long for me to realize the essence, which was that an actor should not imitate or copy another actor if he can help it because the actor who im- presses you has consciously and even painstakingly moulded an overt personality and laid down his own ground rules to bring that personality effectively on the screen. I understood very early on, while I was at Bombay Talkies itself, following such films as Milan (1946), that I had to be my own inspiration and teacher and it was imperative to evolve with the passage of time.

It was also wonderful to be in the company of Raj Kapoor again after our Khalsa College days. Raj was happy to know I had seriously entered the profession of film acting. ‘I told you, didn’t I?’ he said, hugging me like a little, excited boy when I was ready for my debut. When we were at Khalsa he used to tell me in Punjabi: ‘Tusi actor ban jao. Tusi ho bade handsome.’ (You should become an actor. You are very handsome.)

As 1945 rolled by, the Second World War was coming to an end and the freedom movement was gain- ing momentum in the country. At the studio every day, Ashok Bhaiyya and S. Mukherjee Sahab would engage in discussions about what they had heard or read. They would seriously discuss Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s speeches and ask me for my opinion. Having had a ‘memorable’ experience when I spoke my mind at the Wellington Soldiers Club in Poona, I thought it best to maintain a discreet silence. By the time I finished my work in Jugnu, our country was heading for its emancipation from British rule. I remember the day – 15 August 1947 – vividly when independence was won for us by the great men and women who fought for it tenaciously and relentlessly for decades. I was walking on the pave- ment near the Churchgate station, quite unnoticed despite having acted in three films – Jwar Bhata (1944), Pratima (1945) and Milan (1946) – when I noticed people were rushing homewards with joy- ous expressions on their faces. It was only when I reached home and I saw the whole family together for a change with every face shining with happiness that I realized it was independence day.

1947: Aghaji discovers his son’s secret profession

Jugnu was released in late 1947.

The film became a hit and the hoardings were put up in many places, including a site near Crawford Market. One morning while Aghaji was supervising the unloading of a consignment of apples at his wholesale shop in the market, Raj’s grandfather, Basheshwarnathji, walked in and the two greeted each other warmly as always.

That morning Basheshwarnathji had a naughty smile playing beneath his moustache. He twirled his moustache and told Aghaji he had something to show him: something that would take his breath away. Aghaji must have wondered what it could be. Basheshwarnathji took him out of the market and showed him the large hoarding of Jugnu right across the road. He then said: ‘That’s your son Yousuf.’

Aghaji told me later on that he could not believe his eyes for a moment but there was no mistaking me for someone else because the face he knew so well was printed large and the blurb on the hoarding was hailing the arrival of a bright new star on the silver screen. The name was not Yousuf. It was Dilip Kumar.

He described to me much later, after he accepted my choice of career, the awful feeling of disappointment that overwhelmed him at that moment. He was naturally very angry. Aghaji did not reveal his anger and hurt pride through harsh words or any other form of resentment.

He was very quiet for some days and did not speak to me. Even at other times, when we spoke to each other in monosyllables, I did not dare to look him in the eye. Soon, the situation became awkward and I did not know what to do.

The thick layer of ice had to be broken somehow. I confided in Raj and he said he knew this was going to happen and the best person to mediate was Prithvirajji. And he was right. Prithvirajji paid a casu- al visit to our home one day. Amma told me when I got home in the evening that the powwow with Prithvirajji had done considerable good and she noticed that Aghaji was a lot more relaxed and cheerful.

Filmistan and Shaheed (1948)

BETWEEN THE PERSONAL AND THE PROFESSIONAL

My contract with Bombay Talkies was coming to an end and there were changes taking place in the stu- dio management. Ashok Bhaiyya had moved out and so had S. Mukherjee Sahab to form Filmistan. As we were no longer fettered by foreign rule, there was a surge of creative activity and spirited unravelling of the communicative powers of the medium. Movies were being made with a sense of introspection, patriotism and social purpose by many talented and dedicated film makers.

I did not hesitate to accept S. Mukherjee Sahab’s invitation to work in the pictures to be made at Filmistan. The beneficial aspect was that he did not talk about a contract or agreement restricting me to work only in his pictures. As it was, the studio employment system was inevitably being replaced by managements seeking services of actors and technicians on a freelance basis with varying remuner- ations commensurate with experience, expertise and track record.

There were many producers who had noticed me then and had called me over to talk about the films they were proposing to make with me in the male lead. S. Mukherjee Sahab was aware of this development and he respected my decision to work in his venture at Filmistan. The film was Shaheed (released in 1948).The subject fired my imagination and I felt it was a wise decision to make a patriotic film .

I was completely in synch with the character in Shaheed because of the social and political climate prevailing at that time and my own patriotic senti- ments were seeking an outlet, which was there for the asking in the well-written scenes and dialogues.

Though the film was directed by Ramesh Saigal, it was the inspiration we got from S. Mukherjee Sa- hab that fleshed out the performances and added momentum to the movement of the narrative.

Kamini Kaushal

Kamini Kaushal had a noticeable fluency in speaking English, which was unusual those days for an act- ress and that delighted S. Mukherjee Sahab who generally preferred to talk in that language. In fact, after a day’s intense work on scenes that called for serious emoting, we formed a small circle for some nice light-hearted conversation, in which occasionally Ashok Bhaiyya also joined. Ramesh Saigal was a good conversationalist and he was the first one to address Kamini Kaushal by her real name Uma (Kashyap) and all of us followed suit.

Shaheed met with deserving success at the box office. My pairing with Kamini Kaushal in that film got an encore from the audiences and Filmistan had us teaming up in Nadiya Ke Paar (released later in 1948) and Shabnam (1949), which became even bigger successes. As far back as the 1940s, the gimmick of pleasing the mass audience by bringing together artistes [in this case Dilip Kumar and Kamini Kaushal] who were believed to share an attraction for each other in the life they lived outside their work environment was as common as it is today.

Stardom bothered me more than it pleased me and I guess I was drawn more intellectually than emotionally to Uma, with whom I could talk about matters and topics that interested me outside the purview of our working relationship. If that was love, may be it was. Yes, circumstances called for us to discontinue working together and it was just as well because, after a few films together, star pairings generally tend to pall on viewers, which is bad for business.

A question I have often been asked is the somewhat intrusive one whether it makes a difference to the potency of the emotions drawn from within oneself in an intimate love scene if the actors are emotion- ally involved in their real lives. My honest answer is both yes and no.

Shifting home to Pali Mala, Bandra

It became imperative now for us to shift our residence to a suburb that was closer to Goregaon (in western Bombay), where many film studios were (and are) situated.Aghaji agreed to shift to Bandra (also in western Bombay). We took a bungalow at Pali Mala in the midst of a cluster of dwellings owned by Goan Christian settlers.

I bought a Fiat car (sometime in the late 1940s) not so much because I needed it but more because my sisters required a vehicle to go out. My first drive was to the Brabourne Stadium. A cricket match was going onI picked up Dr Masani and we reached the stadium in time to be ushered to the enclosure meant for special inviteesI found myself seated beside an impressive looking man wearing an unbuttoned jacket over his shirt. He was talking to a lean man seated on his right, tilting his broad frame to hear what the lean man was trying to tell him on seeing me. I took my seat and since both of them smiled at me I thought it fit to greet them. They were ob- viously my co-religionists because they were in the Muslims’ enclosure, so I said ‘Salaam Alaikum’ (peace be upon you), and they returned my greeting warmly.

After the match started and progressed, the impressive looking man felt he should speak to me. He introduced himself as Mehboob Khan and introduced his friend as Naushad Miyan. It was the begin- ning of two enduring friendships and professional relationships in my life and career. Naushad Miyan (basically a music composer) had written the story of what became the film Mela and he invited me to meet him and the director, S. U. Sunny, the following week. Both Naushad Miyan and Mehboob Khan had seen Shaheed.

My meeting with Naushad Miyan took place in Sunny’s small office where he narrated to me briefly the story of Mela. He also told me that they had recorded the title song with which they would like to start the shooting. It was a bit awkward for me to ask questions about the details of the story but I thought it would be a risk if I did not know enough to be in a position to accept the film.

DK’s ground rules as an actor

I must mention here that my work choices from the very beginning were not governed by the remu- neration I was offered.

This was something I learned from Nitin Bose and Devika Rani who were my first and most influential teachers. While working with Nitin Bose during the making of Milan (1946), I understood how vital it is for an actor to get so close to the character that the thin line between the actor’s own personality and the imagined personality of the character gets ruthlessly rubbed off for the time when you are involved in the shooting. To get that close to the character it is very important to know everything about the character and his mind and emotions.

While I was deeply involved with Milan, one day Nitinda asked me whether I had seriously read the novel Nauka Dubi (written in Bengali by the Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore). I told him that I had read the translation given to me and, of course, the script, which was very detailed. We were pre- paring to shoot the scene in which the character named Ramesh has travelled all night by train and has reached Varanasi (now in Uttar Pradesh), where he has to immerse the mortal remains of his mother in the Ganga. He performs his duty with a heavy heart, tired and weather-beaten as he is bound to be after the overnight journey. Nitinda asked me if I had given sufficient thought to the state of Ramesh’s mind and his feelings during the journey by train sitting up all night holding the urn securely so that the last remains from it did not spill out. Nitinda also asked me to think over the scene, imagining the disturbed state of Ramesh’s mind as he sat looking at the urn and remembering his mother who used to talk to him affectionately and serve him food and wake him up in the mornings with a cup of hot tea.

He finally asked me: ‘Don’t you think Ramesh would have thought to himself, this is my mother who has been reduced to ashes, my mother who had such soft hands and such gentle eyes?’ I told Nitinda frankly that I had not thought so deeply because such depth was not in the script. Nitinda of course understood but he gave me a valuable lesson that has stood me in good stead. He made me write four to five pages expressing my feelings as Ramesh during the journey. I sat up half the night and wrote and rewrote until I was overcome by sleep.

The next day the scene was to be shot at a location in Ghodbunder in Bombay. When the camera started to roll I was into the scene emotionally and the ex- perience was satisfying for me and Nitinda.

That was how Nitinda groomed me. He explained that a good script always helped an actor to per- form effectively but there were areas beyond what was given to him in the script that were waiting to be explored by one who wished to rise above the given areas in his performance.Devika Rani had advised me and all the actors she employed at Bombay Talkies that it was important to re- hearse till a level of competence to perform was achieved. In the early years, it was a necessity for me to rehearse, but, even in the later years, her advice stayed with me when I had to match a benchmark I had mentally set for myself.In fact, I am aware that I am known for the number of rehearsals I do for even what seems to be a simple scene.

Let me give an example. There was a situation in Nitin Bose’s Deedar (1951), in which Ashok Bhaiyya and I had lines to deliver and the cue for his lines had to be taken from my lines. In our re- hearsals we had mutually decided that the word ‘mulayam’ (meaning soft) in my dialogue would be his cue to speak and turn his face towards me. Being a Bombay Talkies man, Ashok Bhaiyya had as much of a fetish for rehearsals as I had and so we had already had almost eight to ten rehearsals. The director told us to be ready for the take and he called for action. When I spoke my dialogue, quite in- advertently, I replaced the word ‘mulayam’ with ‘narm’ (also meaning soft) and Ashok Bhaiyya was thrown off track. I don’t know what went wrong with me that day. The director called: ‘CUT’; and I need not tell you what followed. Though not one to lose his temper, Ashok Bhaiyya gave me a piece of his mind and said gruffly: ‘OK, now we will stick to “narm”.’

Mela (1948)

GETTING BACK TO MELA (RELEASED IN 1948), I REMEMBER driving to Filmistan Studios with S. U. Sunny, discussing the story on the way. When we reached the studio and walked on to the stage, the title song was being played. The description I got from the director of the proposed picturization was absolutely flat. I suggested changes in the situation and the picturization, which were appreciated by the director and Naushad Miyan, the music composer.

Mela was the first film Aghaji watched in a cinema house because Naushad Miyan persuaded him to view itwith Chacha Ummer.Aghaji looked at me and his expressive eyes showed his concern for something that was going on in his mind. He then said: ‘Look if you really want to marry that girl, I can talk to her parents. Just tell me who she is. You don’t have to be so unhappy.’

For a moment, I failed to fathom what was being spoken by both of them. Then it dawned on me that they were speaking about Nargis,* the heroine in Mela, carried away as they were by the story and the performances. I could clearly see their inability, as first-time viewers of a feature film, to accept and enjoy it all as make-believe.The picture was memorable for the enduring friendship that began between me and Naush- ad Miyan and between me and Nargis.

With Nargis it was a no-holds-barred friendship. It was as though we were of the same gender because she was not at all hesitant to join the menfolk in their talks and was not one to be shocked if a bawdy remark was made in front of her.Nargishad improved vastly when we were cast in Mehboob Khan’s Andaz (1949). It was a delightful ex- perience doing Andaz because Raj Kapoor was there in the film and it was like the times we spent at Khalsa College when we played soccer.Raj and Nargis shared a chemistry that made a good equation for their scenes together. With Nargis, in front of the camera, I shared a different equation, and I felt all through the making of Andaz that she was there and yet not there when we emoted scenes that had to have a certain temperature

I was able to attain that ease with Madhubala in Tarana (1951), which has remained, for many reasons, one of the films I would count among the memorable ones I have done in the early years of my career.

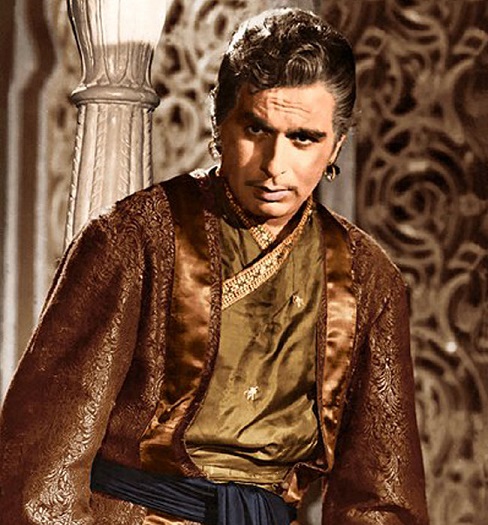

Aan

Mehboob Sahab was known for the offbeat casting in his films. He had cast me in a swashbuckling villager’s role in Aan (1952), in total contrast to my public image at that time of a tragedian.Aan was a worldwide hit and he felt triumphant that he had made India’s first film [with prints by] Technicolor.

The psychiatrist recommends comedy

We held meetings in Mehboob Sahab’s house or at Naushad Miyan’s residence and it was in one such meeting (I think in the early 1950s) that I disclosed my intention of switching over to comedy since I had been clinically advised to do so by one Dr W. D. Nichols who had been introduced to me by Dame Margret Rutherford and Dame Sybil Thorndike with whom I had long discussions when I had met them through a drama coach in London.

Dr Nichols was kind enough to spend a good one hour with me when I called on him. I shared my fears with the eminent psychiatrist and he assuaged me saying it was not a cause for worry since many of his celebrity patients from the acting profession had come to him with the same fears and he had told them what he was going to tell me. He suggested a quick change of the genre of films I was do- ing. He explained to me that most actors who repeatedly worked in the same genre of films found it difficult to overcome the dichotomy that confronted them between the two lives they were leading.

The unreal sometimes, or rather most times, became so overpowering that the real called for protection from caving in and getting submerged. I had been playing characters who were ill-fated and a morbid outlook had seized me as a result of my extreme involvement and my living the character beyond the working hours.

Dr Nichols said ‘My dear young man, Spend more time in leisure that you enjoy or with friends you feel happy to be with.’

I understood what he meant. Indeed, I had got so involved in the work I was doing that I had unin- tentionally distanced myself from my brothers and sisters, seeing them only for a short time on return- ing home every night and I had almost stopped playing football and cricket with my friends.

Mehboob Sahab and Naushad Sahab just stared at me. They were unable to grasp my dilemma They thought I was crazy to go and seek advice from psychiatrists and drama coaches in England. They named other actors who were sticking to the same genre and had no problems whatsoever. I went home somewhat distraught.

Azaad (1955)

The next day I went over to meet S. Mukherjee Sahab and I told him I had seen a Tamil film [Malaikallan (1954), featuring M. G. Ramachandran (MGR) as the hero], which a producer from Madras (now Chennai) had arranged for me to see. The producer Sriramulu Naidu wanted to make it in Hindi and it meant a complete change of screen image if I chose to do it. K. Asif also happened to be presentand, smiling provocatively, he said: ‘Karke dikhaiye.’ (Let’s see you do it.) Asif’s look was like a gauntlet thrown down for me. Mukherjee Sahab had no second thoughts about the decision I was waiting to take. He said: ‘Go ahead and do it.’

Azaad (released in 1955), in many ways, was the first film that gave me the much-needed confiden- ce to forge ahead with a feeling of emancipation and sense of achievement.I was woken up by V. V. Purie Sahab [then a film financier, was the father of Aroon Purie of India Today fame] at midnight and he was calling from Delhi to tell me the great news that the film was a hit.The delirious caller to wake me up early next morning was Sriramulu Naidu and I felt ever so happy for him because he had such confidence in me that he gave me absolute freedom to incorporate whatever ideas occurred to me to make the script and screenplay entertaining. It was also a pleasant experience working with Meena Kumari, for whom the film offered a welcome switchover to light- hearted acting from the serious acting she came to be known forNaidu and I hit it off quite unexpectedly from the very first day of shooting.I discovered a latent flair in me to assimilate both Tamil and Telugu as speedily as I had learned Bengali

Madhubala: Mughal-e-Azam is announced

It amused me when Sakina Aapa [elder sister] asked me one evening whether I knew what was going on between Raj and Nargis. I told her that she should ask Raj who used to drop in unexpectedly and make his presence felt in our quiet house by talking to everyone and demanding the aromatic milkless tea that Aapa made specially for him.

Did it happen with me? Was I in love with Madhubala as the newspapers and magazines reported at that time? As an answer to this oft-repeated question straight from the horse’s mouth, I must admit that I was attracted to her both as a fine co-star and as a person who had some of the attributes I hoped to find in a woman at that age and time. We had viewers admiring our pairing in Tarana and our work- ing relationship was warm and cordial.She filled a void that was cry- ing out to be filled – not by an intellectually sharp woman but a spirited woman whose liveliness and charm were the ideal panacea for the wound that was taking its own time to heal.

The announcement of our pairing in Mughal-e-Azam made sensational news in the early 1950s be- cause of the rumours about our emotional involvement. In fact, K. Asif (the film’s director) was ec- static with the wide publicity and trade enquiries he got from the announcement. It was not anticip- ated or planned that it would be in production for such a long period as it was and Asif was aware of Madhu’s feelings for me because she had confided in him during one of their intimate talks.As was his wont, he took it upon himself to act as the catalyst and went to the extent of en- couraging her in vain to pin me down somehow. He went on to advise her that the best way to draw a commitment from an honourable and principled Pathan, brought up on old-world values, was to draw him into physical intimacy.

He did what any selfish director would have done for his own gain of creating riveting screen chemistry between actors who are known to be emotionally involved. Also, I sensed Asif was seriously trying to mend the situation for her when matters began to sour between us, thanks to her father’s attempt to make the proposed marriage a business venture.

The outcome was that half way through the production of Mughal-e-Azam, we were not even talking to each other. The classic scene with the feather coming between our lips, which set a million imaginations on fire, was shot when we had completely stopped even greeting each other.

It should, in all fairness, go down in the

annals of film history as a tribute to the artistry of two professionally committed actors who kept aside

personal differences and fulfilled the director’s vision of a sensitive, arresting and sensuous screen

moment to perfection.

Interestingly, Asif had wanted me to play Prince Salim in a project he had started way back when I was working in Nadiya Ke Paar (1948). He had invited me over to his house and introduced me to his wife, the Kathak danseuse Sitara Devi, with whom an instant rapport developed as we talked about classical Hindustani music and dance forms.Asifsaid he liked everything about me but he felt I was rather too young to play Prince Salim at that juncture.

He remarked: ‘You have the royal bearing of a prince but I want an older look.’ I told him he was right. Rather prophetically, he then declared that in the future he would make a film relating the love story of Salim and Anarkali on a scale that would inspire awe and he would cast me as the romantic prince.

He announced the film shortly with Sapruji (D. K. Sapru. who later became a character actor) in the lead but due to financial curbs he could not go beyond a few reels.

So when he approached me years later with the proposal of Mughal-e-Azam, it was like a dream come true for him. I had by then moved up the echelons of stardom I worked on Salim’s personality by fine-tuning my instincts appropriately to create a screen persona who closely matched the descriptions I read in some fine books I got hold of in the Anjuman Islam school library. I could always depend on my friend Mohammad Umar Mukri (a short-statured charac- ter actor) to help me out on such occasions. He rummaged through bookshops and got me whatever he could lay his hands on.

To cut the story short, I think I more or less succeeded in approximating my get-up and screen persona of Prince Salim to the picture I had formed in my mind. I knew at the very start of the project that I was not going to get much help from Asif. He had numerous concerns to deal with as the director and in his typical manner he laughed away my worries saying: ‘Just be yourself. You are Prince Yousuf.’

Madhubala: a marriage is contemplated

MADHUBALA WAS NO DOUBT THE RIGHT CHOICE FOR THE ROLE of Anarkali. She grasped the essence of the character in no time with her agile intelligence. Yes, there was talk of our marriage while the shoot- ing of Mughal-e-Azam was in progress in the 1950s. Contrary to popular notions, her father, Ataullah Khan, was not opposed to her marrying me. He had his own production company and he was only too glad to have two stars under the same roof.

Had I not seen the whole business from my own point of view, it would have been just what he wanted, that is, Dilip Kumar and Madhubala holding hands and singing duets in his productions till the end of our careers. When I learned about his plans from Madhu, I explained to both of them that I had my own way of functioning and selecting projects and I would not show any laxity even if it were my own production house. It must have tilted the apple cart for him and he successfully convinced Madhu that I was being rude and presumptuous. I told her in all sincerity and honesty that I did not mean any offence and it was in her interest and mine as artistes to keep our professional options away from any personal considerations. She was naturally inclined to agree with her father and she persisted in trying to convince me that it would all be sorted out once we married.

My instincts, however, predicted a situation in which I would be trapped and all the hard work and dedica- tion I had invested in my career would be blown away by a hapless surrender to someone else’s dictates and strategies. I had many upfront discussions with her father and she, not surprisingly, remained neut- ral and unmoved by my dilemma.The scenario was not very pleasant and it was heading inevitably to a dead end.I was truly relieved when we parted because I had also begun to get an inkling that it was all very well to be working together as artistes but in marriage it is important for a woman to be ready to give more than receive. I had grown up seeing Amma’s steadfast devotion to the family and her flawless character as a woman. I was now increasingly seized with the feeling that I was letting myself into a relationship more on the rebound than out of a genuine need for a permanent companion.

What’s more, I did not want to share a lifetime with someone whose priorities were different from mine. Besides, she certainly would have been drawn to other colleagues in the profession, as I found out, and they to her but that wasn’t an issue because I was myself surfacing from an emotional upheaval at that point of time.

Amma was ailing with an acute respiratory disorderAwidespread canard was that the break-up between Madhu and me caused the heart condition that finally claimed her life.The heart condition that was diagnosed was congenital in her

Madhubala’s father, in a bid to show me his authority, got her entangled in a lawsuit with producer-director B. R. Chopra by suddenly making a fuss about the long outdoor work scheduled for Naya Daur (eventually released in 1957) giving her heart condition as a reason for her withdrawal from the film. He came up with an excuse about his daughter’s inability to work at the outdoor locations in Bhopal and Poona for the film after some reels were canned.

Chopra Sahab was upset and very angry because it was made clear at the very outset, when the script narration was given to the artistes, that it was an outdoor film. Chopra Sahab, who held a bachelor’s degree in law before he took to journalism in Lahore in the pre-independence period, took legal steps to challenge the whimsicality on Madhu’s part. As a fellow artiste, I could do little but fall in line with the producer’s decision to replace Madhu with Vyjayantimala, when all sincere and genuine efforts on my part to negotiate an easy compromise without making the issue public became futile.

I did feel sorry for Madhu and wished she had the will to protect her interests at least on the professional front without thoughtlessly bowing to her father’s wishes all the time. Such submission had an adverse impact not only on her professional reputation but also on her health needlessly. Vyjayantimala and I had worked with a fair measure of respect and understanding in Bimal Roy’s Devdas (1955) and Chopra Sahab had liked her work.I was made to appear as if I had got Madhu out of the film while the truth was that her father pulled her out of the project to demonstrate his authority.

Devdas, Naya Daur and beyond

Bimal Royapproached me sometime in 1954 with the idea of play- ing the title role in the film DevdasIt troubled me initially to experiment with the rendering of a character who carried a heavy measure of pain and despondency under the skin and could mislead the more vulnerable youth to be- lieve that alcoholism offered the best escape from the pain of losing in love.

Bimalda knew from his own sources that I was a stickler for making the writing base of a film strong. So he made it comfortable for me to participate in the writing work along with his formid- able team comprising Nabendu Ghosh and Rajinder Singh Bedi, among others.

Vyjayantimala

Vyjayanti and I carried forward the professional understanding and bonhomie we had developed dur- ing Devdas to the six films we worked in thereafter. She emerged as a capable artiste and a quick learner.

After Devdas, when we came together for Madhumati (released in 1958), she had made con- siderable progress in her rendering of scenes and dialogue. She was diligent and took pains to grasp the pace and complexity of the situations, especially when the surrealistic and metaphysical scenes and situations were given to her for study before we went before the cameras to film Madhumati.All the three films, Devdas, Madhumati and Yahudi (1958) that I did under Bimalda’s direction gave me the pleasure of knowing a man who believed in perfection and hard workIn Madhumati the incentive was the construction of the narrative and the layers of unpredictability in it.There was the latent fear that the audience may just not identify with a reincarnation concept.People who tried to find fodder for gossip mills were actively seeking a liaison between me and Vyjayanti when I selected her to play Dhanno in Gunga Jumna (released in 1961) after working together in four well-received films prior to it. (The fourth film was S. S. Vasan’s Paigham, 1959.)

The reality was that I had been observing her painstaking efforts to raise the scale and temperature of the emotions demanded by the challenging scenes she had to do with me for Devdas.I would particularly mention the scenes in which Devdas is deeply troubled and mortified by the irresistible attraction he feels for her and she, knowing it all with her feminine sixth sense, makes no bones about boldly unravelling her bruised feelings as the woman he needs but does not want to love.As a co-star, she was very well mannered and spoke respectfully to the senior actors and unit mem- bers.

She came to the sets with her grandmother (Yadugiri Devi) who doted on her and made sure she got star treatment from her producers. Following her grandmother’s instructions, no doubt, to assert her star status, she hardly lingered on the sets after the shooting and preferred to remain undisturbed in the make-up room and enjoy the vegetarian cuisine she brought along.

We were unable to fathom, though, how she used the litres and litres of milk her grandmother ordered each day first thing on her arrival at the shooting venue. Did she wallow and bathe in it like Cleopatra? My brother Nasir, who liked to play pranks, once brought a milk-laden buffalo, while we were shooting outdoors for Gunga Jumna, and he wanted to tie it to a pole outside the special makeshift make-up room we had put up for Vyjay- anti. I got to know of it in good time and I rebuked and stopped him

Paigham, 1959

On one occasion, when we were filming Paigham in Madras I was travelling with [SS Vasan Sahab]by train to Madurai, he told me he was unsure of the development of the scene we were to shoot the next day for Paigham as it was a tricky one where the heroine would muster up all her feminine guile to find out the hero’s feelings for her. He said he had been applying his mind to create a humorous situation but it was just not happening.

I told him I had seen a foreign film in which the hero and heroine meet on the terrace of a building where they hope to share some quiet moments. The heroine asks the hero if he had dated any girls or desired anyone before he met and befriended her. He tells her he will not reveal all that because it will upset her. She tells him don’t be silly, we are grown-ups and there is no question of my getting up- set. Her hair keeps falling over her face and he leans forward and moves the hair back to see her face clearly. Then he begins to tell her about a girl .... He sees the colour recede on her face and her eyes betray her anxiety. Finally he tells her: ‘See, I told you ....’ She is almost in tears. He then tells her that the girl he was describing and talking about was none other than the girl sitting in front of him.

I suggested to Vasan Sahab we could do the scene a bit differently. The hero would do all the talking and the heroine would respond with expressions. He would go on telling her about the woman he is in love with and arouse her envy and curiosity. She would try hard to hide her reactions but the audience can see that she is getting edgy and jealous from the expressions that flit across her face involuntarily.

The next day in the studioI told Vasan Sahab: ‘Let’s do some rehearsals’. He was surprised that I had my lines ready. I told him that I had the lines in my mind in the train itself when we had discussed the scene and fi- nalized it. The scene turned out to be one of the highlights in the film. It was during the making of Naya Daur that I noticed Vyjayanti’s ability to feign a rustic character’s mannerisms with conviction. When I was scripting Gunga Jumna, I felt she would fit the role of Dhan- no if she took pains to render the Bhojpuri dialectwith the right accent and inflex- ions.

Naya Daur

The making of Naya Daur is a small story by itself. When B. R. Chopra completed the story on paper, he took it to Mehboob Sahab to get an opinion.Mehboob Sahab read the story and found no meat in it for entertainment. He told Chopra Sahab it could be made into a fine documentary on the doomsday awaiting the labour force in the country once machines replaced them but, as a feature film, it was not a great idea.

He was called the ‘great mumbler’ for the way in which he mumbled some of his dialogues, for instance ‘Maa’ in Mughal-e-Azam.

However, look at his poker face in this frame. His beaming screen mother wants him to get married to Rajni, whom he loves and wants to marry. However, like a good Indian/ South Asian son of 1957 he is not supposed to admit to feelings of romantic love in front of his parents. So, while he is bursting with happiness inside, Shankar (Dilip Kumar) pretends to agree to marry Rajni (played by Vyjayanthimala) only to please his mother. He even feigns that he is not sure who this Rajni is.

This classic bit of Method Acting can be viewed at roughly 57:30 in the colourised version of the film Naya Daur

Above: Leela Chitnis (who plays his screen mother) with Dilip Kumar in Naya Daur (1957)

Chopra Sahab listened to the senior film maker’s opinion respectfully, but he had made up his mind that he would make the film if I agreed to act in it. He told me this emphatically after he gave me the idea in a nutshell. I liked the idea except for the climax in which originally the bus was to be beaten by the tonga (a horse-drawn carriage) by some kind of manipulation. It did not seem logical to me.

However, I kept the thought to myself since there was no chance of my accepting the film.

Initially, it seemed as if Chopra Sahab and I were not destined to come together. When Chopra Sa- hab came to me with the Naya Daur script, I was committed to a film Gyan Mukherjee had specially written with me in mind. So I told Chopra Sahab that his project would have to wait till Gyan Mukher- jee’s film went on the floors and he completed the shooting. I liked the basic premise of the Naya Daur story and the intent, but it was not possible for me to work on two scripts simultaneously because that would lead to overlapping of thoughts and ideas, which could affect the content of both the films ad- versely.

I explained to him that it was for this very reason that I had not welcomed the idea of doing Pyaasa (when offered to me by producer-director Guru Dutt) because I was then involved in Devdas and, though the subject of Pyaasa was very inviting for a serious actor like me, I felt there was a similarity in the shades of the character of Devdas and the hero of Pyaasa. The logic was quite simple: if I had accepted Pyaasa unthinkingly it would have been released close on the heels of Devdas and one of them would have overshadowed the other. It made bad business sense to me. (Guru Dutt eventually played the hero in Pyaasa)

Chopra Sahab was visibly troubled but he agreed to wait. As Destiny would have it, Gyan Mukher- jee’s film did not take off due to some financial hassles and I was ready to consider Naya Daur. It was during the production of Naya Daur that I began to form the story idea of Gunga Jumna in my mind.Naya Daur turned out to be a huge successIt was magnanimous of Me- hboob Sahab to accept how wrong he was and how right Chopra Sahab was in judging the potential of the subject.

On the domestic front

I don’t think my elder brother Noor Sahab and my younger broth- ers really knew what it entailed for me to keep my professional values from slipping in the face of the challenge of generating a substantial income to meet the growing demands for household expenses, fees, clothes, pocket money, books, daily travel and so on.

I remember a producer coming to me in the late 1940s with a briefcase full of money and the script for a film he intended to make. I had not seen him before or heard of him. He narrated the story to me and I listened till he came to a point where the hero starts moving around the village astride a buffalo. I stopped him there and asked: ‘Why a buffalo?’ He replied it was his idea of blending comedy into the hero’s character. When I asked if I could make necessary changes in the script, he said that I could but the buffalo had to be retained.

I stealthily looked at the rickety briefcase on the table, which had the hard cash I needed so much at that point of time. It was shaking a little due to the breeze coming from the window and seemed to be leering at me silently.

I then politely refused to spend more time listening to the story and he couldn’t believe that I was turning down such an impressive story and such a good amount of money. The spontaneity with which I refused the briefcase enhanced my self-esteem and firmed up my resolve to work according to my terms.

Gunga Jumna and after

THE STORY OF GUNGA JUMNA WAS developing in my subconscious. It was neces- sary for me to relaunch my brother Nasir – he was facing a slump in his career after having acted in a few films – and also to have my own production house. The subject was such that it needed sound financing to depict it on celluloid in the manner I had visualized.

I knew Shapoorji Mistry and Pallonji Mistry quite well. I had met them informally at their homes and the manner in which the ladies had placed some Persian delicacies on the table when we sat down for tea reminded me of the goodies that always appeared on the table in our house at PeshawarShapoorji heard the story of Gunga Jumna from me and he had no doubts about its viability but my brother Nasir felt it was not a good idea for me to play an outlaw. He insisted that the public would not accept me joining the dacoits and taking refuge in their lawlessness to get back at the wicked zamindarI thought about it and concluded that I would go ahead with the venture since Shapoorji was confident about the movie’s success.

I felt it was time for me to make a picture that raised some critical issues about the people of rural India who had gained little from the country’s independence from foreign rule. The oppressed farmers and tillers of the soil were leading a life of slavery and were being exploited and swindled by the mercenary landlords.The situation has not changed much today, more than half a century after both Mehboob Khan’s Mother India (1957) and Gunga Jumna (1961) exposed the exploitation of farmers, for whom the soil they till and plough is sacred.