Delhi: Qudsia Gardens

Contents |

Delhi: Qudsia Gardens,The Ridgein 1902

This section was written between 1902 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

Extracted from:

Delhi: Past And Present

By H. C. Fanshawe, C.S.I.

Bengal Civil Service, Retired;

Late Chief Secretary To The Punjab Government,

And Commissioner Of The Delhi Division

John Murray, London. I9o2.

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

THE SURROUNDINGS OF THE CITY, CHIEFLY ON THE NORTH AND WEST SIDES, THE MINOR BUILDINGS WITHIN THE WALLS, AND THE FIELD OF THE BATTLE OF DELHI, 11TH SEPTEMBER 1803.

Qudsia Gardens

ON the north of the city, outside the Kashmir Gate, are the pretty Kudsia Gardens, on the Jumna bank. These were constructed by the Kudsi Begam, mother of the Emperor Ahmad Shah, whose reign was the culminating period of the decay of the Moghal Empire. The walls which formerly enclosed it have been removed for the most part, and the river which once flowed under the terrace, on the east side, is now far away from it; but the fine though ruined gateway remains, and a handsome mosque, still bearing marks of the siege of 1857, stands near the south-east corner of the public recreation grounds.

In the Kudsia Garden are the sites of the Mortar Battery, and of Siege Battery No. III, Opposite the south end are the breaches of the Water Bastion and Kashmir Bastion, and outside the south-west corner are the Nicholson Garden and the cemetery where General Nicholson lies At the north-west corner stands Ludlow Castle, the residence of the Commissioner, Mr Simon Fraser, in 1857, and now the Delhi Club. The site of the left section of No. II Siege Battery is in the grounds of the Club, near the east wall

As the longest portion of the City Walls generally seen by visitors to Delhi is that on the north side, it may be noted here that these defences as they now stand were constructed between 1804 and 1811 by the British Government, after the attack on the city by the Mahrattas,1 at which time the Kashmir Gate was also reconstructed.

The Moghal walls were apparently never properly completed, and after they had been seriously damaged by a severe earthquake in 1720, offered no serious obstacle to any enemy; and it was by a special irony of fate that in the summer of 1857 the British forces found themselves unable to batter down the ramparts which the British Government had itself raised. The walls were never any real defence against the fire of heavy artillery, as was proved in less than a week in September 1857, and under the conditions of modern warfare are an entirely negligable item. They are fully described, from a military point of view, by Colonel Baird Smith, in his report upon the Siege and Assault (p. 200), and as they were in 1857, so they are now. They are well built for the most part, though some curiously rough bits exist between the Kashmir Bastion and the river.

The Ridge

The Ridge is described in detail in Delhi In 1857: The scene of the siege and assault , and only the objects of antiquarian interest, situated on it, will be noticed here. The Lat of Asoka, and the so-called Observatory were situated in the Kushk-i-Shikar, or country palace of Firoz Shah, known also as Jahannuma, or World-displayed, and the Chauburji Mosque probably stood outside that.

[1 The attack on Delhi by the troops of Jaswant Rao Holkar lasted from 7th October to 15th October, 1804: the defence was conducted under Colonel Ochterlony by Colonel Burfn, after whom the Burn Bastion is named. The first attack was made at the south-east angle. After the batteries here had been destroyed by a sally, the curtain between the Turkman and Ajmir Gates was breached, but fresh defences were constructed inside the wall, and no assault of the breach was pressed home. Finally an attack, alao repulsed, was made on the Lahore Gate, a demonstration being made on the Kashmir Gate. Like the actual siege of 1857, which began on 6th September and ended on the 14th, the siege of 1804 lasted for nine days only. The Mahratta forces consisted of 70,000 men and 130 guns; the British force of two battalions and four companies of sepoys, two corps of irregular cavalry, and some 800 Tilangas, who had recently deserted from the enemy; and of these eight companies were lost to the defence, as they were needed to protect the palace and secure the person of the king, whom Holkar desired to get into his own hands. General Lake had ordered that if the city could not be successfully defended, the troops were to retire into the palace and hold that; Colonel Ochterlony wished to do this, but Colonel Burn, who was in military command, refused. The extraordinary achievement of the defence was allowed to pass practically unnoticed, and Colonel Burn never received any recognition of his gallant feat of arms.]

The origin of this palace is thus described by the annalist of the king

In the year 774 H.=1373 A.D., the Wizir Malik Mukbil, entitled Khan Jahan, died, and his eldest son, Juna Shah, succeeded to his office and titles. During the year 776 H., on the 12th of Safar, the king was plunged into affliction by the death of his favourite son, Fatah Khan, a prince of great promise, and the back of his strength was bent by the burden of grief. Finding no remedy, except in patience and resignation, he buried him in his own garden (now the Kadam Sharif, and performed the customary ceremonies upon the occasion. On account of the excess of his grief, the shadow of his regard was withdrawn from the cares of state, and he abandoned himself entirely to his sorrows.

His nobles and counsellors placed their heads on the ground, and represented that there was no course left but to submit to the divine will, and that he should not show further repugnance to administer the affairs of his kingdom. The wise king acceded to the supplications of his friends and well-wishers, and, in order to dispel his sorrows, devoted himself to sport, and in the vicinity of new Delhi he built a wall of two or three parasangs in circumference, planted within the enclosure shady trees, and converted it into a hunting park. The ruins of it remain to this day.

Mr Finch, in the memoirs of his travels as far as Lahore, specially mentions this site in the following terms

A little beyond Delhy are the relicks of a stately hunting house, built by an ancient Indian king, which has great curiosities of stone work about it. Amongst the rest there is a pillar all of one entire stone, some 24 feet high, and as many under ground (as the Indians say), having a globe and half moon at top, and divers inscriptions upon it. This, according to the tradition of the country, a certain Indian king would have taken up and removed, but was prevented in his design by the multitude of scorpions that infested the workmen.

An account of the removal of the Buddhist columns to Delhi will be found on The Lat on the Ridge was broken by an explosion early in the eighteenth century, and lay on the ground for 150 years; and, in consequence, the surface of the stone is rougher, and the letters of the original inscription are less distinct than in the case of the Lat in the Kotila of Firoz Shah, which has stood erect there for 550 years, and no doubt stood erect at Topra for 1600 years.

The Observatory, which stands on the highest point of the Ridge, was in all probability the tower upon which a chiming clock was erected by the king. It is popularly known as the Pir Ghaib, or the Hidden Saint, perhaps from the underground galleries which connected it with the plain to the west, and of which vestiges may be seen throughout the slope on that side. On this side too, near the south corner of the area round Hindu Rao’s house, and at the level of the plain, is a fine baoli, with a very long flight of steps, belonging to the same period as the Kushk-i-Shikar.

Opposite Jahannuma, and probably by the ford under Metcalfe House, Timur and his horde crossed the Jumna in 1398, after taking and destroying Luni, the site of which still rises prominently on the left bank of the river, and after slaying all the captives with the army to a number, it is alleged, of 100,000. At Jahannuma the Moghal camp was attacked by the Sultan, Mahmud Khan, and his minister, Mallu Khan, but the attack was repulsed, and the camp was carefully secured by abattis of trees, and by chaining lines of buffaloes, and placing iron caltrops in front of these, to break the charge of the war elephants.

The Chauburji Mosque, so called from the four domed corner rooms which once stood upon the raised platform, is a structure of the time of Firoz Shah, which was used as a mausoleum, and altered in certain respects in the last century. The restoration, made since 1857, has almost entirely destroyed all resemblance to the building of the Mutiny time.

Wazirabad

Near the extreme north end of the Ridge, where it ceases abruptly on the bank of the river, is the picturesque shrine of a local Muhammadan saint, by name Shah Alam, in the limits of the village of Wazirabad. This is built on the banks of a channel which drains the Bawari plain, and is spanned by a fine bridge above the north-west corner of the building. Shrine, gateway and courtyard, and mosque, bridge, and paved causeway alike, belong to the period of Firoz Shah Tughlak (1365-1390 A.D.), and in spite of vile whitewash, they form one of the prettiest architectura groups at Delhi, when viewed from the north side of the bed of the stream, from which two flights of steps ascend to the enclosure.

It was at Wazirabad that Timur and his Moghal horde encamped and crossed the Jumna on 1st January 1399 A.D., after having deluged Old Delhi with blood and utterly destroyed the central Muhammadan power of the day in North India. Six years later the great Sultan died on the borders of China, having meanwhile sacked Baghdad and captured the Turkish Emperor, Bajazet.

West of Wazirabad and north of the Grand Trunk Road is the Bawari plain, the site of the Imperial Darbar of 1st January 1877, and the Coronation Darbar of 1st January 1903. Two miles further west along the main road at the site of Badli-ki Sarai and the village of Pipal Thalla is the battle-field of 8th June 1857

Shalimar Gardens

Less than a mile to the north-west of the Sarai and across the railway line are the scanty remains of the Shalimar Gardens, which must be visited on foot. It may be doubted if these were ever fully finished, as they were begun by the Emperor Shah Jahan only in 1653, though Bernier speaks of them as fine gardens, with handsome and noble buildings (inferior, however, in his opinion, to Versailles or St Germain), and the Emperor Aurangzeb was formally crowned there.

At any rate, they were no doubt ruined at an early date by some one of the many invaders of Delhi in the eighteenth century—Nadir Shah encamped here on quitting Delhi— and but little now exists to mark their former grandeur. The depressions of the three principal tanks, and the long water-channel connecting these, lie outside a fine grove of mango trees, which still shades the highest pool, overgrown by lotus, and forming a very picturesque bit; and a half-ruined summer-house, called the Shish Mahal, stands at the southwest corner of the garden.

The designation given to it by the Emperor was Khanah-i-Aish-wa- Ashrat, the Home of Joy and Companionship; the name by which it and the more famous gardens of the Emperor Jahangir, or, more properly of his consort, Nur Jahan, at Lahore and Kashmir are known, is derived from two Hindi, or Sanscrit words, also meaning the Abode (shála) of Joy (már). For a time after 1803 the gardens were used by the Resident at Delhi as a summer retreat, and General Ochterlony contracted in them the fever of which he died thirtytwo years after his defence of Delhi.

Roshanara Gardens

Returning from the Badli-ki Sarai and Shalimar, the road to the right at Azadpur may be followed to the Roshanara Gardens. The point of separation is that where our force divided after the battle on 8th June 1857, and advanced in two bodies on the Ridge This road runs through gardens on both sides, passing on the left hand the Ochterlony Garden, or Mubarik Bagh, which was one of the finest round Delhi. Near the Sabzi Mandi and the Roshanara Gardens are two handsome gateways, each of three arches, and known as Tirpulia, built in 1728 by one Mahaldar Khan Nazir, or Superintendent of the household of the King Muhammad Shah, and bearing his name.

They formed the entrances of a bazar, on the right side of which is a garden made by the same official, approached by a handsome portal. There are very few notable buildings in or near Delhi of subsequent date to this, the principal being two of the Golden Mosques and the tombs of Safdar and Jang and Ghazi-ud-din Khan.

Half a mile nearer to Delhi, and two miles from the Kashmir Gate, are the gardens of Roshanara Begam, standing a little back on the right. The present grounds, which are extremely pretty, have been formed by the combination of several gardens into one, that from which the whole is named lying on the east side.

It was made in 1650 by the Princess Roshanara Begam, a daughter of the Emperor Shahjahan, and the devoted adherent of Aurangzeb against Dara Sheko and his partisan sister, Jahanara Begam and she lies buried in it, after having survived her brother’s accession for thirteen years. The grave enclosure, which is open to the sky, is placed in the middle of a pavilion which no doubt once stood in the centre of the garden; the tomb itself carries earth in the recess hollowed in it, like that of her sister at Nizam-ud-din. The gate of the garden on the east side was once decorated with beautiful encaustic work.

Across the canal, and reached by the road which runs south from the front of this gate is an interesting Armenian graveyard, containing a number of tombs which are much the oldest Christian graves in Delhi. It is known by the name of the family of D’Eremao, which was once connected with the imperial court.

About three miles from here, and four miles from Delhi, down the Rohtak road is a fine old masonry aqueduct, called the Pul Chaddar, by which the Western Jumna Canal was carried towards the city across the cut from the Najafgarh Jhil. This, and various bridges across the canal were blown up in 1857 to prevent the enemy crossing to the rear of our position.

Returning through the Sabzi Mandi from the Roshanara. Gardens to the city, the quarters of Kishanganj and Paharipur, from which the enemy so persistently annoyed and attacked our position in 1857, are passed on the south side of the Western Jumna Canal. The bridge across this on the road running south from the end of the Ridge leads in 300 yards to a solitary grave and monument in an open space on the right hand.

The former marks the resting-place of Captain G. C. M‘Barnett, killed in the attack of the 4th Column on 14th September 1857, and the latter records the bravery and losses (four sergeants, three corporals, and twelve privates) of the 1st Bengal Fusiliers near this spot on that day. “Familiar with the aspect of Death which they had confronted in so many battles from which they had always emerged victorious, they met his last inevitable call here with intrepidity, falling on the 14th September 1857 in the faithful discharge of their duty. This monument, erected by the officers and fellow soldiers of the 1st Regiment European Bengal Fusiliers, is their remembrance, which is part of its glory. The rest remains with the Lord.”

Outside the Kabul Gate of the city once stood the fine garden and tomb, known as Tis Hazari, of Malika Zamani Begam, the high-spirited mother of the Emperor Muhammad Shah, who freed her son from the Syad tyranny; and outside the Lahore Gate stands a third mosque built by a wife of Shahjahan, known as the Sarhandi Begam. It is not perhaps generally recollected that the Lady of the Taj died in 1630, two years after this Emperor ascended the throne, and that the bereaved husband proved by no means inconsolable during the thirty years of his reign. Both in size and in architectural merit, this is the poorest of all the buildings inaugurated under the auspices of the founder of modern Delhi, the domes being low and ungainly in shape; they are constructed of red sandstone, which is very unusual in domes of such a size.

Nearly a mile south of this gate and mosque, and across the channel which connects the Western Jumna and Agra Canals, is a fine old Sarai, known as the Idgah Sarai, and behind it to the south is the Dargah, or Sacred Enclosure, of the Kadam Sharif —the Holy Footprint, which must be approached on foot. This is a very interesting and picturesque building of the time of Firoz Shah, having been raised by that king as the last resting-place of his eldest son, Fatah Khan, in the year 1375. The tomb enclosure is surrounded by a citadel wall, like the tomb of Tughlak Shah, constructed, no doubt, to protect it against the attacks of the Moghals, as it lay, of course, outside the city of Firozabad.

The shrine is approached by two fine outer gateways, and consists of a quaint arcaded enclosure round the grave of the prince, over which the sacred imprint, sent by the Khalifa of Baghdad to Firoz Shah, is placed in a trough of water. It is worth while descending the steps on the north side of the mosque, in order to view the west end of the enclosure from the outside. South of the outermost gate of the outer walls is a fine stone tank; and on this side is situated the principal Muhammadan cemetery of Delhi, unhappily much neglected. On the Ridge west of the Kadam Sharif is the Idgah, a fine enclosure which merits a visit, which also must be made on foot. The view of the city from this point is very pleasing.

Ajmir Gate

Following the road to the left from the main road past the west of the city to Paharganj and the Kutab, we pass round the hornwork enclosing the Mausoleum and College of Ghazi-uddin Khan, and reach the Ajmir Gate.

The former specially deserves to be seen, as one of the few remaining specimens of a religious endowment, similar to those of the middle ages in Europe, comprising a place of worship, the tomb of the founder, and a residence and place of instruction for those who were to have charge of both, all built in his lifetime. Ghazi-ud-din was son of the first Nizam - ul - Mulk of Hydrabad.

He became the leading noble of the Delhi Court when his father returned to the Deccan after the events of 1739, and died in 1752 A.D., on his way to assert his succession to the Hyderabad Territories. The courtyard, approached through a gateway of which the wings are thrown forward, is surrounded on three sides by a double tier of chambers for students, like the colleges of Samarkand and Bokhara: on the west side the mosque, built of very deep coloured red sandstone, and with very rounded domes, fills the centre, and the south of it is the grave of the founder, enclosed by a beautiful pierced screen of fawn-coloured stone, with doors elaborately carved with flowers.

This corner is, perhaps, quite one of the most picturesque bits in Delhi. For a long time the building, which had been closed eighty years after the founder’s death for want of funds, was occupied by the police: it is now again devoted to educational purposes in connection with the Anglo-Arabic school.

From the Ajmir Gate—the wooden doors, which are no doubt much what those in the Kashmir Gate were in September 1857, should be noticed — the straight road runs to the Sita Ram Bazar which turns to the right to the Kala or Kalan Masjid, standing a little back on the west side from the main street. This was probably the principal mosque of the city of Firozabad, which extended further west than this, as distinguished from the Citadel or Kotila of Firoz Shah and its mosque, and is a curious building, well meriting a visit.

It is reached by a high flight of steps, and like other mosques built about 1380 by the latter of the two great Wazirs who bore the name of Khan Jahan in the reign of Firoz Shah, consists of a courtyard, surrounded on three sides by a simple arcade, borne by plain squared columns of quartzose stone, with a dripstone over the arches, and on the west side by a mosque chamber of three rows of similar columns, each carrying five arches.

The corner towers and outer walls of the mosque are all sloped inwards; there are no minarets, and the call to prayer was made from the roof of the terrace. It would appear from Bishop Heber’s journals that for a long time prayers were not held in this mosque. The graves of the founder of it and of his father were destroyed in the troubles of 1857.

Three other mosques, built by them in the same style but of more interesting arrangement, exist at Nizam-ud-din, Khirki, and Begampur Near the Kalan Masjid are two historically interesting graves of a date of 150 years earlier. On the left side of the road opposite the mosque is the tomb and cemetery of Turkman Shah, after whom the Turkman Gate of the city is called, a militant saint of the first period of Muhammadan conquest and settlement, who died in 1240 A.D. A little to the north, reached by the Bulbuli Khana lane at the point where the Sita Ram Bazar ends, is a small isolated enclosure containing two graves, of which the larger is, according to old tradition, that of the Sultan Raziyah, El Malika Raziyah, Ibn Batuta calls her who was killed and buried in the same year as the above.

There is no reason, I think, for distrusting the popular tradition in this case, as it is on contemporaneous record that the Sultan was buried on the banks of the Jumna, and that the city of Firozabad included the area of her grave; and we may reasonably believe that we see in this humble tomb the last resting-place of the first Empress of India, known like her predecessors and successors as Sultan.

About 200 yards to the north-west from the Jumna Mosque, and conveniently reached from there, is the Jain or Saraogi Temple of Delhi, the elegant decoration of the porch of which is specially commended by Mr Fergusson, and well deserves a visit, which must be made on foot. The times and conditions for visiting the interior can be ascertained at the Temple, and are known to the local guides.

Raj Ghat and other ghats

To the east of the Sonahri Mosque of Javed Khan may be seen a cross at the bottom of the slope of the southern glacis of the fort, marking the site of the old Daryaganj cemetery. East of this again is the Raj Ghat Gate, with a ramp ascending from the river below, and south of both is the garden of the little cantonment of Daryaganj, in which the native regiment of the Delhi garrison is quartered, and the officers of the regiment reside.

This was the original cantonment of Delhi after 1803; but the garrison was subsequently located beyond the Ridge, and in the Mutiny the quarter was mainly occupied by subordinates of the Arsenal, and of various departments of Government. The tale of the strenuous defence made by a number of these against the mutineers will be found on page 106.

The house held by them was that now numbered five, the first on the left beyond the road leading up from the Khairati Gate, by which, as by the Raj Ghat Gate, the mutineers of the 3rd Light Cavalry entered the city on finding the Calcutta Gate closed, and being directed by Captain Douglas to leave the ground below the king’s apartments in the palace. On the north side of the road above the Khairati Gate is the mosque of the Zinat-ul-Masajid, or Beauty of Mosques, built in 1700 by one1 of the daughters of the Emperor Aurangzeb.

The building is a fine one, and well deserves a visit: the steps leading up to it from the roadway are particularly picturesque. The mosque was used for military purposes for many years after 1857, and during that time the tomb of the foundress, which stood on the north side of the enclosure, was removed.

The only other buildings in Delhi which call for any notice are the Mosque of Roshan-uddaulah (1745 A.D.), on the right hand of the Feiz Bazar, leading to the Delhi Gate of the city, and the Fakhr-ul-Masajid, or Pride of the Mosques, built in 1728 A.D. inside the Kashmir Gate. The latter is a very graceful mosque—the former is a clumsy one, far inferior to the Sonahri Masjid of Javed Khan, built three years subsequently to it.

The Ridge: a backgrounder/ 2017

Jayashree Nandi & Jasjeev Gandhiok, August 22, 2017: The Times of India

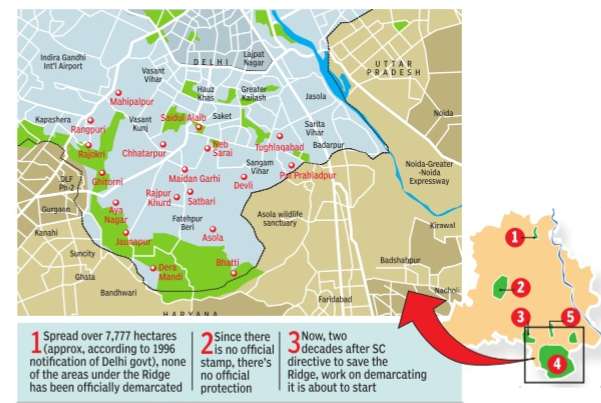

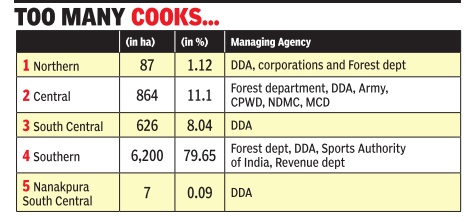

In the 20 years since the Supreme Court ordered the preservation of the capital's green lung, the Ridge, the revenue and forest departments have managed to demarcate just one portion of the sprawling, but much encroached forest land. The revenue department informed the National Green Tribunal on August 11 that it had completed the delimitation of Jaunapur village in the southern Ridge and handed over the land to the forest department for notification.

Officials said this small step still re quired the addition of more portions to the demarcated land before the forest department could begin notifying the expanses as “forest“ area. The exercise is lagging behind the time frame of six months set for the forest department in 2013 by NGT for the final notification of the Ridge and the settling of the rights of people residing within its boundaries. The forest department did begin work in Asola, but the people moved NGT claiming rights to the land. It also came to light that the digitised maps prepared by the two departments did not match.

Apathy by successive governments had left the 7,700-hectare Ridge vulnerable to encroachments, and it is now entangled in litigation. Legally, the Ridge is not a reserve forest. A 1994 notification had intended to declare all forest areas in Delhi, including the Ridge, as reserve forests under Section 4 of the Indian Forest Act. But the demarcation and adjudication of land rights de mands were nev er completed.

R e c e n t l y, exasperated by the inordi nate delay in demarcation, NGT fined Delhi govern ment Rs 2 lakh. “It is regrettable to note that except for taking prevaricated stands on each occasion, the respondents are displaying clear disdainful conduct in frustrating the order of this tribunal,“ the bench said. r In its affidavit filed with NGT on August 10, the revenue department disclosed that the work of demarcating was awarded to a demarcating was awarded to a company in July . “On August 4 and 5, the final handing over of forest land to forest department was done in the presence of the district magistrate (south) and deputy conservator of forests,“ the affidavit stated. The forest department has erected pillars to mark off the forest area.

Officials said portions that appeared encroachment free on satellite maps were selected on priority for demarcation first. After Jaunapur, the revenue department has also completed the delineating of forest land in Pul Pehladpur in the southern Ridge and begun the process in Ghitorni, Rangpuri, Tughlakabad and Rajokri. “The demarcation report along with drawings has been forwarded to the forest department on Au gust 3 for necessary ac tion at their end,“ the revenue department affidavit claimed.

Forest officials revealed that noti fying of the areas as forests can be done only when the chunks were large enough. “Cur rently, we are being handed only small pockets.

Once we get a collectively large area from the revenue depart ment, we will fence it off. We expect a lot of areas to be notified by the end of the year,“ said a senior forest official.

Forest activists, however, are losing patience. Sonya Ghosh, a petitioner in the NGT, pointed out that despite ongoing litigation in the green tribunal, three illegal roads in Rajokri forest were still being used by heavy vehicles. “Forest officials are posted there and yet these vehicles are not stopped. I don't think the forest department has the will to comply with NGT orders,“ fumed Ghosh.

Ghosh alleged that the forest department had detailed maps of the Ridge but ended up demolishing a house that was legally not encroaching on the forest, with the result that the case went to court and stalled the tentative process of marking off the forest area.

Raj Panjawani, Ghosh's advocate in NGT, insisted the government had to take hard decisions. “It's very simple why the process of demarcation is taking so long. It's politics,“ he snapped. “The decision to make the Ridge encroachment free will make some people very unhappy.“