Dutee Chand

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Achievements

August 14, 2018: The Times of India

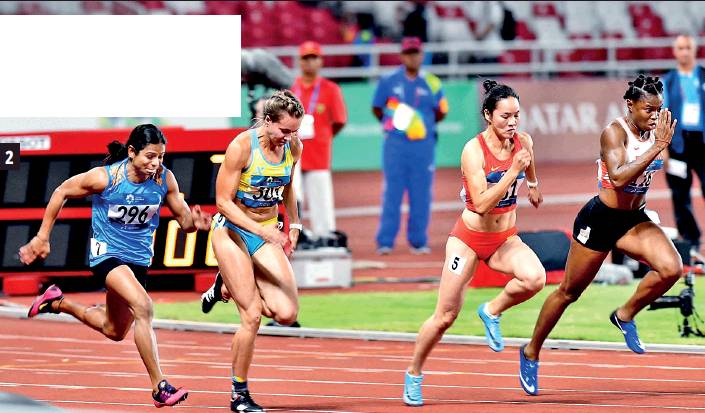

The Odisha athlete, the fastest Indian woman, has come a long way since failing a gender test. The ace sprinter will be hoping to break new ground at the Asiad as she attempts to win medals in the women’s 100m and 200m events in which Indians have struggled to make the podium. The last medal in 100m – no Indian has won a gold – came through PT Usha in 1986.

Early life

Shan A S, July 13, 2016: The Indian Express

Dutee Chand, the 'golden girl', who has qualified for Rio Olympics in the 100 m and 4x100 m relay, becomes a girl again.

There is a small window facing the street in Dutee Chand's room. The sunlight peeping through it is not enough to light up the two-bedroom house shared by a family of eight. Opposite the window, on the wall of the house across the street is a crude painting of a rice plant.

That window was Dutee’s outlet to the world for two years while she went through the humiliating experience of being subjected to a hyperandrogenism test, seen by many as a test of gender. Pursued by media and fighting the maelstrom of identity raging within her, she remained indoors, gazing at that reed of grass from that window.

It was a test of resilience as the girl -- yes, girl -- from the village of Gopalpur, about 90 km from Bhubaneswar, took the case to the Court of Arbitration for Sports, and won its verdict. Now, the taunts have turned into paeans: Dutee Chand, the 'golden girl', who has qualified for Rio Olympics in the 100 m and 4x100 m relay, the girl who became a girl again.

On a rainy afternoon, sitting by Dutee's window, her elder sister Saraswati recollected the hardships the sprinter and the family endured after the Incident.

“I remember her coming home after the incident. She was brought home by two coaches. There was only silence in our house for two months. It was like a mourning. We hardly cooked. Dutee would stand here at this window. Sometimes, she would go to that corner and silently weep. Occasionally, she would explode with anger. Sometimes, she became delirious. Much of that time, she became distant, sitting still like a doll. We were afraid if she was going to harm herself,” says the sister.

Dutee’s success on the track had got her a job, and the family looked up to her. “We had been struggling financially until Dutee got a job. It was a big relief. Our parents were weavers. Between them, my father and mother made about Rs 3000 per month.”

Dutee took to athletics after her elder sister. Saraswati’s purpose in running was to get herself a job, any job. She would practice on the banks of the river Brahmani near their house. “One day, while running on the sand, I spotted Duttee behind me. I had never seen her doing that. She told me she had been doing it secretly for a long time. She had been running on my footprints. How had I missed that! And then I thought 'now this girl will also run, get a government job and help the family',” Saraswati recalled.

Government jobs were something to run for. The Chand family home was a thatched hut. The sisters’ parents, Chakradhar and Akhuji, wove in the ‘verandah’ of the hut on an ancient handloom. It barely paid for the food.

Saraswati's husky voice cracks as she relives those days. “Till I got a job, we had never had royal food.”

She means non-vegetarian dishes.

“Survival was our biggest challenge. Good food was a luxury. We lived on tomato curry. Tomatoes were cheap. On days when we couldn't afford even that, we dipped our rotis in black tea.”

It wasn’t only poverty. There was its sibling, social humiliation, to endure. “There is a grocery shop in the market nearby, where our father bought food on credit,” says Saraswati, her eyes now glinting in remembered anger. “When the payment got due, the shopkeeper would make him wait. Those who paid in cash got served first. That was the rule. There were days my father used to go to get rice for our supper at 8 pm and be back at 11.” The sisters can’t get themselves to forgive the shopkeeper to this day.

It was Saraswati who made the breakthrough. She ran for the state, and it got her a job in the Odisha Police in 2005. Dutee, running in her sister’s footsteps, made it through several years later, and it turned the tide for the family.

The girls’ jobs changed things but slowly. The food got better, if not right royal. The hut became a house and the parents were forbidden to go that shop ever again. The ancient loom is still in the verandah, treated more as an heirloom on which Chakradhar insists on weaving a scarf or two as homage to his ancestral profession.

Freed of bread-winning responsibilities, Chakradhar and Akhuji turned to prayer. Whenever the girls ran, Akhuji lit a lamp for her idols of Maa Tarini, Lakshmi and Hanuman, Dutee’s favour god.

And then the hyperandrogenism controversy broke upon Dutee. The mother was inconsolable. “I was broken when I heard of it,” Akhuji says. “How could it happen? She was born a girl, competed as a girl and won medals as one. And then one morning, someone says she's not a girl. How can that happen?”

The family turned to its fait to keep Dutee’s spirits up, telling her countless times about the travails that even Lord Rama had to endure.

In their formative years, when the sisters ran on the banks of the Brahmani in shorts, it caused an uproar in the village. “Why are you allowing the girls to run in skimpy clothes,” villages would stop Chakradhar in the streets to ask. He used silence as defiance. “They were against the girls running and I defied them. Now Dutee has proved that my defiance was valid,” he says now, beaming.

The village too has learnt to accept the girls, and even takes pride in them now. The Chands’ neighbor, Bipin Bihari Guin, now thinks the sisters’ fame can bring drinking water to the village. “The village is facing a lot of issues like scarcity of drinking water and power cuts. We feel Dutee's achievements will draw the attention of authorities to these issues.”

Now the village is united in praying for Duteee’s return to laurels, perhaps even an Olympic medal. For Dutee's younger sisters, there is also the promise of chocolates from abroad, which sister always remembers to bring after a competition overseas.

“We have an Olympian who didn't have the fortune to taste chicken curry in her childhood,” chuckles Utkal Guin, Dutee’s classmate and neighbour.

Out on the street, not far from Dutee’s once sad window, stands a violet Nano, wrapped in body cover. It’s the car someone gifted to Dutee chand after she won in the school nationals some years ago. It’s little used, bar for taking Dutee’s younger siblings out on a spin around the village. It waits, a symbol of a small fortune and a sea change.

Family

Sister's blackmailing forced Dutee to come out

SUJIT.BISOYI, May 22, 2019: The Times of India

Odia sprinter Dutee Chand, who has revealed her same-sex relationship, said on Tuesday she was forced to do it as her elder sister was blackmailing her for a sum of Rs 25 lakh.

“As I have been in a relationship with a girl of our village for the last three years, my elder sister (Saraswati) was continuously threatening to expose our relationship in the media whenever I failed to give her whatever she demanded. She was threatening that I won’t be able to concentrate on sports once my relationship get exposed,” said Dutee, addressing a news conference.

The 23-year old athlete also alleged that her elder sister had once beaten her up which she had reported to the police. Though the sports fraternity and gender rights activists have hailed Dutee’s coming out as a gay, the Asian Games medalist has been facing the ire of her family. Dutee’s mother Akhuji has objected to her daughter’s relationship.

Saraswati, also a former athlete and now working with Odisha Police, had alleged that Dutee was being misguided by some persons who have been trying to siphon off her money. Asked about her mother’s objection to her relationship, Dutee said her mother must have been influenced by someone to make such statements. “My mother is alleging that I am not supporting my family financially, which is not true. I am aware about my duty towards my parents and family. I have been extending all help, including financial, to my parents,” Dutee said.

The sprinter, who is preparing for World Championship and Tokyo Olympics, said she has not done anything wrong by having a relationship with a girl. She said her father and other siblings have no objection to her relationship. The sprinter also requested the media not to spread anything which may adversely impact her career or socially harm her partner.

Responding to Dutee’s fresh allegations, Saraswati said it was not true. She said Dutee is being “blackmailed and pressurized” by some people who want her money.

Dutee’s village turns its back on her

Sudeshna Ghosh, June 3, 2019: The Times of India

Dutee’s village turns its back on favourite child

Gopalpur: Sometime in 2013, Gopalpur, a nondescript village in Odisha with less than 600 inhabitants and the nearest town 17 km away, sprinted into the country’s imagination. Dutee Chand, a girl from a povertystricken family, had made headlines as the under-18 national 100 metres champion. She repeated her feat in the 100 as well as 200 metresdash at the senior national championships in Ranchi. It was also the year she won bronze at the Asian athletics meet in Pune and made it to the finals at the World Youth Championships.

Dutee, whose family and equally impoverished neighbours made a living as weavers, had arrived — and how. It was the kind of story that sports films are built around. Thrown into the limelight along with Dutee, Gopalpur, in Odisha’s Jajpur district, basked in her halo too. After years, perhaps endless decades in anonymity, the village had in its midst a national hero. Gopalpur adored her.

May 2019 — when Dutee became India’s first openly gay athlete — changed all that. Gopalpur’s residents now say they are are embarrassed to mention the name of the ace sprinter who put their tiny village on the Indian and global map. To many, the 23-year-old athlete’s declaration of same-sex love was a watershed moment in Indian sports. Back home, though, Gopalpur has condemned her.

“We were proud that a weaver’s daughter from here won medals. But all of us were shocked to know about her relationship,” said Benudhar, president of Gopalpur Weavers Co-operative Society.

Dutee’s own family has been brutal in their criticism of the sprinter. “What she is doing is immoral and unethical. She has destroyed the reputation of our village. I can’t believe...my own daughter...,” Chakradhar Chand, her father, trailed off.

To many youngsters, Dutee was until recently a source of both deep envy and great admiration. But the icon has quickly fallen off the pedestal. “We have only seen such things in movies. We don’t behave like this here. She was one of our own, but she let us down,” said a 21-year-old woman who did not wish to be identified.

Dutee herself is unperturbed. “No one likes to make their personal life public. I had planned to settle down with my partner. But my family got wind of our relationship and my sister threatened that she would tell the world about us and shame us. So I decided to tell everyone myself. Now that I have done it, I’m at peace,” she said.

Being brave is something that comes naturally to her — like her quick, strong strides on hard ground. Born into a poor family with nine members, Dutee trained like a maniac for a better future, practicing on the banks of the Brahmani river, jogging on uneven, kuccha village roads. She knew it was the only way out of penury. In 2014, when she won gold at an Asian event, the Athletics Federation of India (AFI) unceremoniously dropped her at the last moment from the contingent for the Commonwealth Games and eventually also for the Asian Games as she tested positive for higher androgen levels. The decision followed a controversial stand on female hyperandrogenism — that female athletes with high androgen levels have an advantage over other competitors — held by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF).

Not one to be brow-beaten, Dutee took her case to the Court for Arbitration for Sport. In July 2015, CAS found IAAF’s stance to be devoid of scientific evidence and set aside the ruling. It was a verdict with global repercussions and Dutee was eligible to compete again. Dutee literally had a great run after that — setting national record at the 2016 Federation Cup in New Delhi and becoming the third Indian to qualify for the Olympics sprint.

Away from the track, too, Dutee was happy. Romance was brewing. A young girl came into her life in 2017 and Dutee saw in her a soul mate. “Four of us, including her brother, were staying at a house in Bhubaneswar. I told her about my struggles and she understood me, we grew close,” Dutee said, adding that her friends have supported her coming out though her fa-mily and Gopalpur haven’t. For now, though, that is enough.

Year-Wise, statistics

2018

Asiad

Biswajyoti Brahma, HAPPY AFTER ENDURING PAIN FOR LONG: DUTEE, August 27, 2018: The Times of India

From: August 27, 2018: The Times of India

It was a sort of redemption for Dutee Chand, who had to undergo “mental agony” following her tryst with hyperandrogenism four years back. The sprinter had to face a lot of hardship and was even dropped from the Indian squad in 2014 due to hyperandrogenism policy of the world athletics body (IAAF). She was later made ineligible before being reinstated following a Court of Arbitration order (CAS).

“Today I feel like a mother who had to bear the pain for nine months but forgets everything once she sees the new-born,” Dutee said after the race. “I am happy to win this medal after enduring pain for long,” she added.

She said she had worked hard for the event in the run up to the event, but could have claimed the gold after the tight fight. “People usually train for four hours a day but I worked for six hours. But my inexperience at competing at international events cost me the gold. The girl who won the top place had experience of several international competitions,” shew said.

Dutee said she was disappointed finishing third in the semifinal and was apprehensive about winning a medal.

2019

Universiade/ 1st Indian to win 100m at global meet

Sabi Hussain, July 11, 2019: The Times of India

Sprinter Dutee Chand became the first Indian ever to win gold in the 100m race at a global meet when she finished first in the event at the World Universiade in Naples.

Soon after her historic win, Dutee Chand tweeted: “Pull me down, I will come back stronger!” The tweet was Dutee’s way of answering her critics, who have time and again raised doubts over her gender and questioned her personal choices.

“That message was for my family, my elder sister Saraswati and mother Akhuji, who are against my same-sex relationship,” Dutee told TOI from Naples, Italy.

“The gold medal is my reply to them and to all my critics that I can manage both my personal life with my chosen partner and the athletics career. I don’t need their advice. I am mature enough to make my own decisions. This medal should silence all who have been talking rubbish about me, my existence and my choice of soulmate,” she said.

In Naples, the 23-year-old from Odisha’s Chaka Gopalpur village clocked 11.32 seconds to win the gold, leading the race from start to finish. She was the first to get off the blocks in the eight-woman final and thwarted a late challenge from Switzerland’s Del Ponte (11.33s) to finish on top. Lisa KwaYie of Germany took the bronze in 11.39s.

The Universiade is an international multi-sport event organised for university athletes by the International University Sports Federation.

“Ever since I revealed my same-sex relationship, people are writing bad things about me on social media. They say my career is finished, I would no longer be able to concentrate on the Tokyo Olympics. My elder sister has polluted the mind of my mother and other family members. But look, today I have won a gold, that too a historic one. It’s all because I have made the right decisions in my career,” she said.

My existence as a normal person was questioned, says the sprinter

The national record holder at 11.24s is only the second Indian sprinter to win a gold at a global event after Assam’s Hima Das, who had clinched the top spot in 400m in the World Junior Athletics Championships last year. But while Hima’s success came at a junior meet and Dutee competed in a senior-level competition.

Dutee, who had a silver each in 100m and 200m at the 2018 Jakarta Asiad, is also only the second Indian track and field athlete to win a gold in the World Universiade. Shot putter Inderjeet Singh had won gold in his event in the 2015 edition.

Dutee said the win at the Universiade liberated her from years of pain and agony as an athlete, after her dream of representing the country at the 2014 Commonwealth and Asian Games was nipped in the bud by the international athletics body’s (IAAF) draconian hyperandrogenism policy. Dutee had to fight her case in the court of arbitration (CAS) in Lausanne to prove to the athletics world that she didn’t compete with higher levels of testosterone and that the ban on her should be lifted, which eventually happened.

“The last few years have been quite painful for me, where my existence as a normal human being was questioned time and again. When I overcame that difficulty, people made a hue and cry about my same-sex relationship. I want to tell the world that I am in a happy space and I know that none would be happier than my partner back in Odisha. Ever since she has come in my life, I have been winning medals all around. She had prayed for my win and her wish has been fulfilled,” Dutee said.

Dutee added that her timings had improved because she had started focusing on her speed in the first 30m of her sprint and not reducing it till the finish line. “Earlier, I used to put a lot of effort and energy in heats and semifinals, now I look to save my energy for the final race.”