Ranchi District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

'Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Ranchi District

District in the Chota Nagpur Division of Bengal, lying between 22 20' and 23 43' N. and 84 o' and 85 54' E. It is the largest District in Bengal, having an area of 7,128 square miles. It is bounded on the north by the Districts of Palamau and Hazanbagh, on the east by Manbhum; on the south by Smghbhum and the Tnbutary State of Gangpur; and on the west by the Jashpur and Surguja States and Palamau District.

Physical aspects

The District consists broadly of two plateaux, the higher of which, on its northern and western sides, has an elevation of about 2,000 feet and covers about two-thirds of its area, while the lower plateau lies on the extreme eastern and aspects southern borders and has only half this elevation. The ghats or passes which connect the two are for the most part steep and rugged, and are covered with a fair growth of timber. In the north-western cornei of the District are situated several lofty ranges of hills, some of them with level tops, locally called fiats, a few having an area of several square miles, but sparsely inhabited and with very little cultivation. The highest point in the District is the Saru hill, about 20 miles west of the town of Lohardaga, which uses to 3,615 feet above sea-level. With the exception of the hills in the north-west and of a lofty lange which divides the main portion of the lower plateau from the secluded valley of Sonapet in the south-eastern comer of the District, the plateaux themselves are flat and undulating, with numerous small hills. The District possesses varied beauties of scenery, especially in the west and south, where bare and rugged rocks alternate with richly wooded hills enclosing secluded and peaceful valleys Not least among the scenic features are the various waterfalls, any of which would in a Western country be regarded as worthy of a visit even from a distance.

The finest is the Hundrughagh on the Subarnarekha river about 30 miles east ofRanchitown , but several others are hardly inferior, e.g. the Dasamghagh near Bundu, two Peruaghaghs (one in Kochedega and one in the Basia thana)^ so called because of the hunareds of wild pigeons which nest in the crevices of the rocks round about all these falls, and the beautiful though almost unknown fall of the Sankh river (known as the Sadnighagh from the adjacent village of Sadn! Kona), where it drops from the lofty Rajdera plateau on its way to the plains of Barwe below. The river system is complex, and the various watersheds scatter their rivers in widely divergent directions. Near the village of Nagra, 12 miles west and south-west ofRanchitown, rise the SUBARNAREKHA (the 'golden line or thread ') and the South Koel (a very common name for rivers m Chota Nagpur, but apparently without any specific meaning) ; the former on the south side and the latter on the north. The Subar- narekha, of which the chief affluents in this District are the Kokro, the KanchI, and the Karkarl, flows at first in a north-easterly direction, passes the town ofRanchiat a distance of about 2 miles, and eventually running due east flows through a narrow and picturesque valley along the Hazanbagh border into the District of Manbhum. The South Koel, on the other hand, starting m a north-westerly direction, runs near Lohardaga, and turning south again, flows across the District from north-west to south-east into Gangpur State and there joins the Sankh? which, rising in the extreme west of the District, also runs south-east, the united stream being known as the BRAHMAN! Withm almost a few yards of the Sankh rises another Koel, known as the North Koel , but this stream flows to the north and eventually, aftei tiaversing Palamau District, joins the Son under the plateau of Rohtas. None of these rivers contains more than a few inches of water during the dry season ; but in the rains they come down in sudden and violent fieshes, which for a few hours, or it may be even days, render them wellnigh impassable. Lakes are conspicuous by their absence, the explanation being that the granite which forms the chief geological feature of the District is soft and soon worn away.

The geological formations are the Archaean and the Gondwana Of the latter, all that is included within the District is a small strip along the southern edge of the Karanpura coal-fields. The rock occupying by far the greatest area is gneiss of the kind known as Bengal gneiss, which is remarkable for the great variety of its com- ponent crystalline rocks. The south of the District includes a portion of the auriferous schists of Chota Nagpur. These form a highly altered sedimentary and volcanic series, consisting of quartzites, quartz- itic sandstones, slates of various kinds, sometimes shaly, hornblendic, mica, talcose, and chloritic schists. Like the Dharwar schists of Southern India, which they resemble, they are traversed by auriferous quartz veins. A gigantic intrusion of igneous basic diorite runs through the schists from east to west, forming a lofty range of hills which culminate in the peak of Dalma in Manbhum, whence the name Dalma trap has been derived. In the neighbourhood of this intrusion the schists are more metamorphosed and contain a larger infusion of gold 1 .

The narrower valleys are often terraced for rice cultivation, and the rice-fields and their margins abound in marsh and water plants. The surface of the plateau land between the valleys, where level, is often bare and rocky, but where undulating, is usually clothed with a dense scrub jungle, in which Dendrocalamus strictus is prominent. The steep slopes of the ghats are covered with a dense forest mixed with climbers. Sal (Shorea robustd) is gregarious \ among the other noteworthy trees are species of Buchanania, Semecarpus, Terminalia, Cearela^ Cassia, Butea^ Bauhinia^ Acacia, and Adina^ which these forests share with the similar forests on the Lower Himalayan slopes. Mixed with these, however, are a number of characteristically Central India trees and shrubs, such as Cochlospermum^ Soymida, Boswellia, Hardwickia^ and Bassia^ which do not cross the Gangetic plain. One of the features of the upper edge of the ghats is a dwarf palm, Phoenix acaulis ; striking too is the wealth of scarlet blossom in the hot season pro- duced by the abundance of Butea frondosa and B* superba^ and the mass of white flowers along the ghats in November displayed by the convolvulaceous climber Parana paniculata* The jungles also contain a large variety of tree and ground orchids.

The Indian bison (gaur) is probably extinct as an inhabitant of the District, but a wanderer from Gangpur State or Palamau may occa- sionally even now be encountered near the boundary. Tigers, leopards, hyenas, bears, and an occasional wolf are to be found in all jungly and mountainous parts, while sdmbar (Cervus unicolor)^ nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus\ antelope, chital or spotted deer, and the little kotra or

1 The gold-bearing rocks of Chota Nagpur have been described by S. M. Maclaren in Records, Geological Survey of Ind^a > vol. xxxi, pt. li. barking-deer (Cervitlus mitntjac] are common in all the largei jungles.

The temperature is moderate, except during the hot months of April, May, and June, when the westerly winds from Central India cause high temperature with low humidity. The mean temperature increases from 76 in March to 85 in April and 88 in May, the mean maximum from 88 in March to 100 in May, and the mean minimum from 63 to 76. During these months humidity is lower in Chota Nagpur than in any other part of Bengal, falling inRanchito 43 per cent, m March. During the cold season the mean temperature is 63 and the mean minimum 51. The annual rainfall averages 52 inches, of which 8-1 inches fall in June, 13-6 in July, 13-7 in August, and 8*8 in September.

History

The history of Chota Nagpur divides itself into four well-marked periods. During the first the country was in the undisturbed possession of the Munda and Oraon races, who may be pre- 18 ory * sumed to have reclaimed it from a state of unculti- vated forest , it was at that time called Jharkand or the 'forest tract.' The second period embraces the subjection of the aboriginal village communities to the chiefs of the Nagbansi family. The birth at Sutiamba, near Pithauna, 10 miles north ofRanchitown, of the first of this race, Phani Mukuta Rai, the son of the Brahman's daughter Parati and the snake god, Pundarika Nag, is a well-known incident of mythology. Whatever the real origin of the family, it is certain that at some unknown time the aborigines of Chota Nagpur, either by voluntary submission or by force of arms, came under the sway of the Nagbansi Rajas, and so continued until they in turn became subject to the Musalman rulers of Upper India.

This event, which may be taken as inaugurating the third period in the history of Chota Nagpur, took place in the year 1585, when Akbar sent a force which subdued the Raja of Kokrah, or Chota Nagpur proper, then celebrated for the diamonds found in its rivers 3 the name still survives as that of the most important pargana ofRanchiDistrict. Musalman rule appears for a long time to have been of a nominal description, consisting of an occasional laid by a Muhammadan force from South Bihar and the carrying off of a small tribute, usually in the shape of a few diamonds from the Sankh river. Jahanglr sent a large force under Ibrahim Khan, governor of Bihar, and carried the forty-fifth Kokrah chief, Durjan Sal, captive to Delhi and thence to Gwalior, where he was detained for twelve years. He was eventually reinstated at Kokrah with a fixed tribute ; and it would appear that the relations thus formed continued on a more settled basis until the depredations of the Marathas in the eighteenth century led, with other causes, to the cession of the Chota Nagpur country to the British in 1765.

A settle- merit was arnved at with the Nagbansi Maharaja m 1772, but aftei a trial of administration in which he was found wanting, the country now included inRanchiDistrict was, along with other adjoining territories, placed under the charge of the Magistrate of Ramgarh in Hazaribagh District. This was in 1816 or 1817. Meanwhile the gulf between the foreign landlords and their despised aboriginal tenants had begun to make itself felt. A large proportion of the country had passed from the head family, either by way of maintenance grants (khorposti) to younger branches or of service grants (jdgtr) to Brahmans and others, many of whom had no sympathy with the aborigines and only sought to wring from them as much as possible The result was a seething discontent among the Mundas and Oiaons, which manifested itself m successive risings in the years 1811, 1820, and 1831 In the last year the revolt assumed very senous proportions, and was not sup- pressed without some fighting and the aid of three columns of troops, including a strong body of cavalry It had long become apparent that the control from Ramgaih, which was situated outside the southern plateau and m reality formed part of a more northern administrative system, was ineffective , and in 1833 Chota Nagpui proper with Dhal- bhum was formed into a separate piovince, known as the South- western Frontier Agency, and placed in the immediate charge of an Agent to the Govemor-Geneial aided by a Senior and Junior Assistant, the position of the former corresponding closely with that of the present Deputy-Commissioner of Ranch!. In 1854 the system of government was again altered, and Chota Nagpur was constituted a non-regulation province under a Commissioner In the Mutiny of 1857 the head bianch of the Chota Nagpui family held firm, though the Ramgarh Battalion atRanchimutinied and several of the inferior branches of the Nagbansis seceded. Chief among these inRanchi District was the zamlndar of Barkagaih, whose property was confiscated and now forms a valuable Government estate The subsequent history of the District has been uneventful, with the exception of periodical manifestations of the discontent of the Munda population in the south and south-east This was fanned dunng the last fifteen years of the nineteenth century by the self-interested agitation of so-called sarddrs or leaders, whose chief object has been to make a living for themselves at the expense of the people, and also by the misrepresentations of a certain section of the German missionaries. It culminated in a small rising in 1899 under one Birsa Munda, who set himself up as a God- sent leader with miraculous powers. The movement was, however, wanting in dash and cohesion, and was suppressed without difficulty by the local authorities, the ringleader being captured, and ending his days from cholera in theRanchijail When the South-Western Frontier Agency was established in 1833, the District, which \\as then known as Lohardaga, included the piesent District of Palamau and had its head-quarters at Lohardaga, 45 miles west of Ranch!. In 1840 the head-quarters were transferred to their present site, and in 1892 the subdivision of Palamau with the Tori fargana was formed into a separate District.

Doisanagar, which lies about 40 miles to the west and south ot Ranch!, contains the ruins of the palaces built in the last quarter of the eighteenth century by Maharaja Ram Sahi Deo and his brother the Kuar Gokhal Nath Sahi Deo, and also of some half-dozen temples erected for the worship of Mahadeo and Ganesh The stronghold of the former Raja of Jashpur, one of the old chiefs brought into sub- jection by the Mughals, is situated about 2 miles north of Getalsud in the Jashpur pargana. The only other relic worthy of note is the temple at CHUTIA, on the eastern outskirts of the town of Ranch!. Chokahatu, or c the place of mourning,' is a village in the south-west of the District famous for its large burial-ground, which is used by both Muhammadans and Mundas

Population

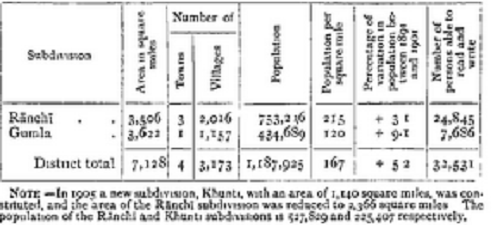

The recorded population of the present area rose from 813,328 in 1872 to 1,058,169 in 1881, to 1,128,885 in 1891, and to 1,187,925 in 1901. The large apparent increase m the first decade may be in part attributed to the imperfections of the first Census. The subsequent growth would have been greater but for the drain of cooly recruiting for the tea and other industries, coupled with a year of sharp scarcity just before the Census of 1901. The more jungly tracts are very malarious, but on the whole the climate compaies favourably with that of other parts of Bengal. The principal statistics of the Census of 1901 are shown below :

The four towns are RANCHI the present, and LOHARDAGA the

former head-quarters, BUNDU, and PALKOT. The density of population

declines steadily from the north-east to the west and south-west ; the

greatest growth has taken place along the south of the District.

Emigration has for many years been very active. In 1897, 4,096

coolies were dispatched to the Assam tea gardens, in 1898, 4,329, and

in 1899, 3,244; in 1900, owing to a failure of the ciops, the number

rose to 6,307; but since then it has fallen to 2,750 in 1901, and to

1,799 i n 1902. The recent diminution is due in part to the very much

closer supervision over the operations of the recruiters provided by

recent legislation.

There is also a large but unrecoided exodus to the tea gaidens of Darjeeling and the Duars, which aie worked with free labour, and to the coal-mines of Manbhum and Burdwan ; during the wmtei months many visit the Districts of Bengal proper to seek employment on earth- work and in harvesting the crops The total number of emigrants at the time of the Census of 1901 was no less than 275,000, of whom 92,000 were in Assam and 80,000 in Jalpaiguri District. Hindi is spoken by 42^ per cent, of the population. The dialect most in vogue is a variety of Bhojpurl known as Nagpuna, which has borrowed some of its grammatical forms from the adjoining Chhattisgarh l dialect. Languages of the Munda family aie spoken by 30 per cent, of the population, the most common being Mundan, \\hich is the speech of 299,000 peisons, and Khana, \\hich is spoken by 50,000, Kurukh or Oraon, a Dravidian language, was returned at the Census as the parent tongue of rather moie than a quarter of the population , but as a matter of fact many of the Oraons have abandoned their tribal language in favour of a debased form of Hindi. Hindus number 474,540 persons (or 40 per cent, of the total); Ammists, 546,415 (46 per cent.), Musal- mans, 41,972 (3-! per cent.), and Christians, 124,958 (10^ per cent). Animism is the religion, if such it can be called, of the aboriginal tubes , but many such persons now claim to be Hindus, and the native Christians ofRanchiDistrict have come almost entirely from their lanks.

Of aboriginal tribes, the most numeious are the ORAONS (279,000), MUNDAS (236,000), and Kharias (41,000). The Oiaons are found chiefly along the north and west, the Mundas in the east, and the Kharias m the south-west of the District. Among the Hindu castes, Kurmls (49,000) and Ahlrs (Goalas) and Lohars (each 37,000) are most largely represented, the last named probably include a large number of aboriginal blacksmiths, Agnculture supports 79 per cent. of the population, industries n per cent., commerce 0-6 per cent, and the professions 1-2 pei cent.

Christians are moie numeious than in any other Bengal District, and in fact number five-elevenths of the whole Christian population of Bengal and Eastern Bengal. Missionary effort commenced shortly before the middle of the nineteenth century, the converts consisting almost entirely of Oraons (61,000), Mundas (52,000), and Kharias '(10,000), The German Evangelical Lutheran Mission was established inRanchiin 1845, and was originally known as Gossner's Mission,

VOL xxi. o

An unfortunate disagreement subsequently took place., and m 1869 it was split up into two sections, the one enrolling itself under the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, and the other letammg the name of Gossner's Mission. The progress made during recent years has been remarkable, the numbei of converts having increased from 19,000 in 1891 to three times that number in 1901. The Mission now possesses 10 stations in the District,, and the workers include 21 European missionaries, 19 native pastors, and 515 catechists, teachers, &c The Church of England Mission, which had its origin from the split in Gossner's Mission, had in 1901 a community of 13,000, compaied with 10,000 in 1891. The Roman Catholic Mission is an offshoot from a mission founded at Singhbhum in 1869, which was extended to Ranch! in 1874. It has now n stations in the District, and its con- verts in 1901 numbered 54,000, or about three-fifths of the total number of Roman Catholics in Bengal and Eastern Bengal. The Dublin University Mission, which commenced work at Hazanbagh m 1892, opened a branch atRanchiin 1901.

Agriculture

The greater part of the District is an undulating table-land, but towards the west and south the surface becomes more broken , the hills are steeper, and the valleys are replaced by ravines where no crops can be grown. Cultivable land ordinarily falls into two main classes : don or levelled and embanked lowlands, subdivided according to the amount of moistuie which they naturally retain ; and tdnr or uplands, which include alike the ban 01 homestead lands round the village sites and the stony and infertile lands on the higher ground. Generally speaking, the low embanked lands are entirely devoted to rice, while on the uplands rice is also grown, but in company with a variety of other crops.

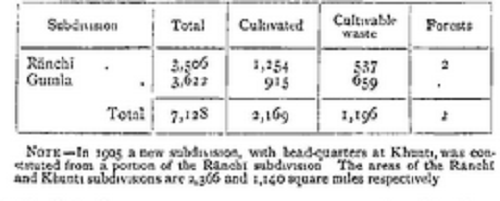

The chief agricultural statistics for 1903-4 are shown below, areas being in square miles :

The chief staple is rice, grown on 1,914 square miles, the upland rice being invariably sown broadcast, while the lowland rice is eithei sown broadcast or transplanted. Other important cereals are gondh or the small millet (Panicum mtliare) and mania , pulses, especially itrd^ and oilseeds, chiefly sarguja and mustard, are also extensively grown. The bhadoi harvest, reaped in August and Septembei, upland nee crops, millets, and pulses; and the kharif leaped latter part of November, December, and January, includes the whole of the nee crops on the embanked lands, sargnja^ and one of the varieties of urd pulse. Though in area there is apparently not much difference between these harvests, the latter is by far the more important of the two owing to the weight of rice taken off the don lands. The rabi harvest in Febiuary is relatively very small, the only important crops being rahar (Cajamts indicus) and s arson. Tea was at one time some- what extensively cultivated, but the soil and the rainfall do not appear to be suited to the production of the finei varieties, and the industry has of late years sensibly declined. In 1903 there were 21 gardens with 2,256 acres under tea and an out-turn of 306,000 Ib Market-gardening is carried on to a small extent in the neighbourhood of the large towns by immigiant Koins from Bihar.

The low land most suitable for embanked rice cultivation has already been taken up, and as the cost of levelling and embanking the higher ground is considerable, the extension of cultivation proceeds but slowly. The native cultivator employs primitive methods and displays no interest in the intioduction of improvements India Government estates experiments have been made with improved seeds, especially of the potato plant, and on the Getalsud tea estate some tanr land has been put under the sisal aloe and experiments m nbie extraction are being made. The construction of tanks for irrigation purposes by erecting dams across the slopes, though they would be cheap and effective, has been but little resorted to, except at Kolebira and in a few villages in Government estates. Cow-dung is used for manuring lowland rice, and ashes for the fertilization of the uplands, especially for cotton. In the lean years 1897 and 1900 advances of Rs. 20,000 were made under the Land Improvement Loans Act, and of Rs. 1,43,000 under the Agriculturists' Loans Act.

No good cattle are bred. Pigs and fowls are largely kept by the aboriginal inhabitants, especially in the remoter parts and on the higher plateaux.

Extensive jungles under private ownership exist in the north-west and south, but the only Government forest is a small Reserve covering 2 square miles nearRanchitown.

The Sonapet area in the south-east corner of the District, which is almost entirely surrounded by the Dalma tiap, has long been known to contain gold , but, from the recent investigations of experts, it appears very doubtful whether its extraction either from the alluvium or from any of the quartz veins can ever prove remunerative. Iron ore of an inferior quality abounds throughout the District, and is smelted by the old native process and used for the manufacture of agricultural imple- ments, &c. In the south-east of the Tamai pargana a sott kind of steatite allied to soapstone is dug out of small mines and converted into various domestic utensils. The mines go down in a slanting dnection, and m one or two instances a depth of about 150 feet has been leached The harder and tougher kinds of trap make good road-metal, while the softer and more workable forms of giamte are of easy access and are much used for the construction of piers and foundations of bridges and other buildings. Mica is found in several localities, especially near Lohaidaga and elsewhere in the north of the District, but not in suffi- cient quantities or of a quality good enough to make it worth mining.

The chief industiy is the manufacture of shellac. The lac insect is bied chiefly on the kusum (Schleichera tnjuga] and palas (Butea frondosa) trees, and shellac is manufactured at some half dozen factones, the largest being at Ranchiand Bundu. Brass and bell-metal aiticle^ are manu- factured at Lohardaga, and coarse cotton cloths are woven throughout the District.

Trade and Communication

The chief exports are lice, oilseeds, hides, lac, and tea, Myrabolams (Termmaha Chebula) aie also extensively exported. The chief imports aie wheat, tobacco, sugai, gur, salt, piece-goods, blankets, and kerosene oil. The principal places of trade are Ranch!, Lohardaga, Bundu, Falkot, and Gobindpur. In the west of the District, owing to the fiequent ghats with only bridle-paths across them, the articles of com- merce are carried by strings of pack-bullocks, of which great numbeis may be met after the crop-cutting season, passing in or out of Barwe to tiade either inRanchior m the Jashpur and Surguja States

No railways enter the District, and practically the whole of the external trade is carried along the cait-road which connectsRanchi town with Purulia on the Bengal-Nagpui Railway This road, and those to Chaibasa and Hazanbagh, with an aggregate length in the District of about 100 miles, are maintained by Government. There aie also 919 miles of road (including 170 miles of village tracks) main- tained by the District boaid The most important of these are a gravelled load, 52 miles in length, connectingRanchiwith Lohardaga, and unmetalled roads fromRanchito Bundu and Tamar, Palkot, Bero, and Kurdeg, and Sesai, whence one branch runs to Lohardaga and another through Gumla There is a ferry over the Koel nver, where it crosses the road to the new subdivisional head-quarters at Gumla, but as a lule femes are little used, as the rivers, when not easily fordable, become furious hill tonents which it is dangerous to cross.

Famine

The District was affected by the famine of 1874, and the harvests F . were very deficient in 1891, 1895, 1896, and 1899, but it was only on the last two occasions that relief operations were found necessary. In 1897 the test works at first failed to attiact labour, and it was hoped for a time that the people would be able to surmount then tiouble without help fiom Government. Dis- tress subsequently manifested itself in the centre of the District, but relief operations were at once undertaken and the acute stage was of very short duration, Altogether 52,710 persons found employment in relief works, and gratuitous relief was given to 153,200 persons, the expenditure from public funds being Rs. 18,000. The District was, however, never officially declaied affected, and relief operations were cairied on only for a few months on a small scale. In 1900 lelief works were opened in ample time , the attendance on them was fai higher than in the pievious famine ; and the distress that would other- wise have ensued was thus to a great extent aveited. The area affected was 3,052 square miles, with a population of about 493,000 persons; and in all, 1,134,287 persons (in terms of one day) received lelief in return foi work and 516,400 persons gratuitously, the expendituie from public funds being 2-3 lakhs. The distress was most acute in the centre and west of the District, but, as fai as is known, there were no deaths from starvation

Administration

In 1902 the District was divided into two subdivisions with head- quaiteis atRanchiand Gumla, and in 1905 a third subdivision was

formed with head-quarters at Khunti. The staff at head-quarters subordinate to the Deputy-Commis- sioner consists of a Joint and five Deputy-Magistrate-Collectois, while the Gumla subdivision is in charge of a Joint, and the Khunti sub- division of a Deputy-Magistrate-Collector.

The chief court of the District, both civil and criminal, is that of the Judicial Commissioner, who is the District and Sessions Judge. The Deputy-Commissionei has special powers under section 34 of the Code of Criminal Procedure to try all cases not punishable with death. The civil courts include those of the Deputy-Collectors who try all original rent suits, of two Munsifs atRanchiand Gumla who have also the powers of a Deputy- Collector for the trial of rent suits, and of a special Subordinate Judge for the combined Districts of Hazaribagh and Ranch! The most common crimes are burglaries and those which arise from disputes about land ; the lattei are very frequent owing to the unsettled nature of rights and areas, the ignorance of the common people, and the greed of indifferent and petty landlords. Murders are unusually frequent, as the abonginal inhabitants are heavy drinkers, believe in witchcraft, and have small regard for life.

The country was originally in the sole possession of the aboriginal settlers, whose villages were divided into groups or paras each undei its manki or chief. These chiefs were subsequently brought under the domination of the Nagbansi Rajas, who became Hmduized and by degrees lost sympathy with their despised non-Hindu subjects The Maharajas in couise of time made large grants of land for the main- tenance of their relatives, military supporters, and political 01 domestic favourites, who fell into financial difficulties and admitted the dikku or alien adventurer to prey upon the land To one or other of these stages belong all the tenures of the District They are very numerous, but can be generally classified under foui heads the Raj 01 Chota Nagpur estate, tenures dependent on the Mahaiajas and held by subordinate Rajas ; maintenance and service tenuies ; and cultivating tenures The second and third classes of tenures are held on a system of succession peculiar to Chota Nagpui, known as putra-pittrddik^ which renders them liable to lesumption in case of failure of male heirs to the original grantee. As the Chota Nagpur Raj follows the custom of primogeniture, maintenance grants are given to the near relatives of the Maharaja. The chief service grants are larmk, given for military service and the upkeep of a militia ; bhiiiya, a similar tenure found in the south-west of the District , ohdur^ for work done as dlwdn \ gkafwa/, for keeping safe the passes , and a variety of revenue-free grants, brdhm- ottar or grants to Brahmans, and debottar or lands set apart for the service of idols. Cultivating tenures may be classified as privileged holdings, ordinary ryoti land known as rajhas> and proprietors' private land or manjhihas. The privileged holdings are those which were m the cultivation of the aboriginal settlers before the advent of the Hindu landlords and the importation of cultivators alien to the village. They include bkulnhafl^ with the cognate tenures known as bhutkhetd (land set aside for support of devil propitiation), ddhkatdr^ pahnai^ and inahati. The last two are lands held by the pahn and mdhato^ the village priest and headman. In some parts the privileged lands of the old settlers are known as khuntkhatti^ and include the pahn khunt, mundd khunt, and the mdhato khunt. The mundd is the village chief respon- sible for the payment of the khuntkkatti rents to the mdnki of the cncle of the villages, while the mdhato ^ a later importation, is the headman from the point of view of the Hindu landlord, whose interests he guards by assisting in the realization of the rent of the rajhas and cultivation of the manjhihas lands These latter include bethkhetd, or land set aside for the provision of labour for cultivation of the remaining private lands. As in other parts of Bengal, attempts to add to private lands aie con- stantly made ; but the tendency received a salutary check from the demarcation, mapping, and registering of bhuinhari and pnvate lands under the Chota Nagpur Tenures Act of 1869 By the original custom of the country, now gradually passing away, rent was as a rule assessed only on the low lands or dons. On an average of ten villages in the Goveinment estates in 1897, the rates per acre for low lands were found to range between Rs 1-2-3 an( ^ R S - 2-1-6, and for high lands between 1 1 and 4 annas, These lates aie very much lower than those prevalent in zamtndan villages, where Rs. 8 to Rs. 10 is often charged for an acre of first-class low land. The uplands, when not paying cash rent, are usually liable to the payment of produce rent known as rukumat^ which varies a good deal in different parts, and the cultivators are liable to give a ceitain amount of free labour (beth begar) to the landlord.

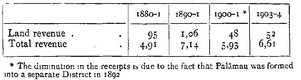

The following table shows the collections of land revenue and total i evenue (principal heads only), in thousands of rupees :

Outside the municipalities of RanchiandLoHARDAGA, local affairs aie managed by the District board. In 1903-4 its income was Rs. 1,04,000, including Rs. 39,000 derived from mtes } and the expenditure was Rs. 1,09,000, the chief items being Rs. 50,000 spent on public works and Rs. 39,000 on education.

The District contains 16 police stations or thanas and 16 outposts. In 1903 the force subordinate to the District Superintendent consisted of 3 inspectors, 33 sub-inspectors, 42 head constables, and 352 con- stables , there was, in addition, a rural police force of 24 daffaddrs and 2,442 chaukidars. The District jail atRanchihas accommodation for 217 prisoners, and a subsidiary jail at Gumla for 21.

Education is backward, only 2-7 per cent, of the population (5-1 males and 0-5 females) being able to read and write in 1901, Great progress is now being made, and the number of pupils under instruction rose from 12,569 in 1892-3 to 19,132 in 1900-1. In 1903-4, 19,074 boys and 2,514 girls were at school, being respectively 220 and 2-7 per cent, of the chilaren of school-going age. There were in that year 857 schools, including 15 secondary, 825 primary, and 17 special schools. The most important of these are the District schools, the German Evangelistic Lutheran Mission high school, the first-grade training school, the Government industrial school, and the blind school, all inRanchitown. The expenditure in 1903-4 was Rs. 1,55,000, of which Rs. 19,000 was derived from Provincial revenues, Rs. 38,000 from District funds, Rs. 700 from municipal funds, Rs. 22,000 from fees, and Rs. 75,000 from other sources.

The District contains 6 dispensaries, of which 3 possess accommo- dation for 49 in-patients. The cases of 18,348 out-patients and 369 m-patients were treated in 1903, and 768 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 18,000, of which Rs. 1,100 was contributed by Government, Rs. 1,000 by District funds, Rs. 5,000 by Local funds, Rs. 3,000 by municipal funds, and Rs. 9,000 by subscriptions. The principal institution is theRanchidispensary. A small lepei asylum at Lohardaga is conducted by the German mission.

Vaccination is compulsory only in municipal areas, but good progress is being made throughout the District, and in 1903-4 the numbei of persons successfully vaccinated was 43,000, or 37-3 per 1,000 of the population

[Sir W. W. Huntei, Statistical Account of Bengal, vol. xvi (1877); F. A. Slacke, Report on the Settlement of the Estate of the Maharaja of Chota Nagpur (Calcutta, 1886) , B. C Basu, Report on the Agriculture of the District of Lohardaga (Calcutta, 1890) , Papers relating to the Chota Nagpur Agrarian Disputes (Calcutta, 1890) ; E. H. Whitley, Notes on the Dialect of Lohardaga (Calcutta, 1896), F B. Bradley- Birt, Chota Nagpitr (1903).]