Ancient Indian Ethnography: Early Inhabitants of Northern India, 1

This article is an extract from ETHNOGRAPHY OF ANCIENT INDIA BY ROBERT SHAFER With 2 maps 1954 OTTO HARRAS SOWITZ . WIESBADEN Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Early Inhabitants of Northern India In the West

We have not yet discussed the problem of determining what people occupied northern India before the Aryans came. Many authors have assumed that it was the Dravidians who had occupied northern and

1 Except for the Pulindas (Gonds), who extended a short distance north of the Narmada, and the Maltos, then in Maldah. See note 1, p. 9.

2 Vedic Index, I, p. 454.

3 Although Tibetan is closely related linguistically to Chinese, the Tibetans today are actually more brown than yellow, indicating admixture with a darker race since epic times in India.

4 Heinrich Zimmer remarked that the early vedic word Dasyu was replaced by 6udra (Altindisches Leben [Berlin, 1897], 117). western India, but I have seen no evidence whatever to support such a theory. 1 I had originally assumed that it was the Bhils who had occupied the area from the Ganges to the western border and from the Himalayas to the northern edge of the present Dravidian territory. There is much to support this belief. The invading Aryans found flat- nosed black Dasyus in the northwest, 2 and black men are the Maha- bharata's Nisadas, and probably the demon Madhayas founci near jthe Himalayas, at Mathura, the Vindhyas and Anarta ; and skulls of proto- Australoid type 3 were found at Mohenjodaro. In short a black primitive people seem to have lived all around the borders of the territory delimited

1 I have found nothing in Sanskrit literature to support such a theory. The theory may have arisen from the fact that the Brahuis, speaking a Dravidian language, live in Baluchistan west of the Indus, but it does not take into account that the Brahuis are not physically similar to the other Dravidians. And they are not of the physical type of the black natives described by the Aryans as living in northern India.

Von Eickstedt's designation of the lightest race that is numerically important in southern India as "(graceful) Indid" and of northern India as "North Indid" is misleading. There is a somatic difference between the two races, though slight; and Guha, with later data, divides von Eickstedt's "North Indid" area among Mediterraneans, proto-Nordics, Alpo-Dinarics, etc.

T.Burrow has presented a large number of Dravidian- Sanskrit word parallels, many of which look like loan words from Dravidian to Sanskrit ("Some Dravidian Words in Sanskrit," Trans. Philol. Soc. 1945 [London, 1946], pp. 79120; "Loan- words in Sanskrit," TPS 1946 [1947], pp. 1 30; "Dravidian Studies VII," BSOAS 12 [1948], 365-396). These studies are not far enough advanced to state from which Dravidian language these loan words were taken into Sanskrit, or when. Professor Kirfel writes me that his unpublished study of these loan words shows that many were cultural terms. But the only cultured Dravidians mentioned in epic times were south of the Vindhyas. If it can be shown that these cultural terms were borrowed by Sanskrit in vedic times, they would present a case for Dravidians in the Indus valley at a very early period. This has not yet, at least, ! been shown.

Certainly the Brahuis must have been joined with the other peoples speaking Dravidian at one time. In the Geography we find Sindhu-Pulindaka which I interpret to mean the Pulindas from the Indus, since the Pulindas were not on the Indus in epic times. A rather cursory comparison of Brahui vocabulary with that of other Dravidian languages led the writer to believe that the Brahui language is most closely related to other north Dravidian languages, spoken by people of comparatively low culture.

The work of A(ugust) Clemens Schoener, Altdravidisches, eine namenkundliche Untersuchung (Erlangen, 1927), has not as far as I know been examined criti- cally by a scholar familiar with Dravidian and the languages of the regions con- cerned, particularly Iranian, with respect to the theory of Dravidians in northern India or their origin.

2 Manu said that tribes without the pale of the castes sprung from the mouth, arms, thighs, and feet (of Brahma), whether they speak the language of the Mlecchas or of the Aryas, are all called Dasyus. But this was the word of a later lawmaker who probably used neither Mleccha nor Dasyu in their original sense.

3 The proto -Dravidian or Veddoid of some writers. above, and the borders of this area were better known to the Aryans than the jungles and desert within it.

The vedic Dasyu was described as krsna-tvac "black-skinned," anas "flat-nosed," and mrdhra-vac "of hostile speech."

The Mahabharata's descriptionjrf Nigada prince Ekalavya as of dark hue, ofjbpdy smeared with filth, dressedjn black andTBearing matted locks on his head 1 might "Be ah early Aryan description of either a Bhil, aTCoIToFa Gond, and for this passage I make the identification of Nisada and T5Eil primarily from the position of one of the Nisada tribes near thejwestern end of the Vindhyas and because the Yadavas distinguished the^ Nisadas from Gonds and Kols. 2 More accurate descriptions of Nisida, ancestorjpf the Nisada, arejfound. The Mahabharata states that he~was short limbed, resembled a charred brand, and had blood-red eyes and black hair; 3 the Visnupurana says he had a complexion like that of a charred stake, flattenecT features, and a dwarfish stature; 4 the Bhagavatapurana describes him as black as a crow, of short stature, arms and legs, with high cheek bones, a broad and flat nose, red eyes, and tawny hair. 5

The Rajputana Gazetteer 6 states that "the typical Bhil is small, dark, broad nosed, and ugly."

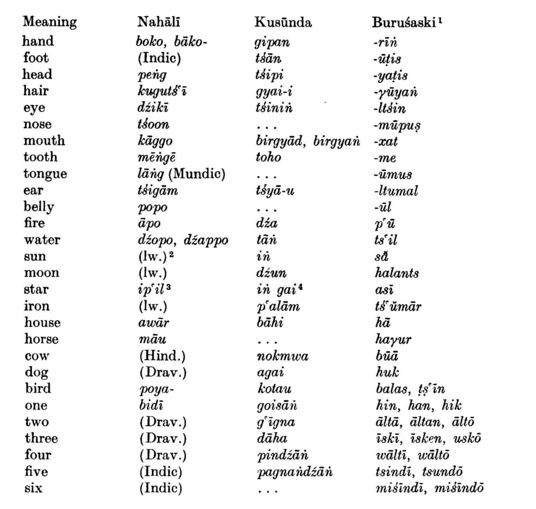

One may ask what language did the Dasyus-Nisadas-Bhils talk? Ethnologists have sometimes considered the Bhils as of a different racial stock from that of the peoples speaking either Dravidian, "Austro- asian," Sino-Tibetan, or Indie languages and we may note here that three languages spoken in or near India have no genetic relationship with any of the above linguistic groups : Nahali spoken in Nimar, Kusunda spoken in Nepal, and Burusaski spoken north of the Dards. Burusaski is rather well known, but the other two languages are so little known that I shall present short vocabularies of each to show that they have no noticeable connection with each other, and it will be apparent to those familiar with the other linguistic groups of India that none of the following languages are even remotely related to Dravidian, "Austro- asian," Sino-Tibetan, or Indie:

2 The Harivams'a, chap. 5, states that from Nisida originated the Nigadas, Tusaras, Tumbaras, Gonds, Kols, and other tribes living in the Vindhyas. Thus while it grouped them all together in an obvious bit of folk etymology, it also distinguished them. (The Tusaras or Tukharas did not live in the Vindhyas but in the foothills of the Himalayas, according to a statement elsewhere in the Hari- vams'a; the error is perhaps due to a copyist.)

I know of no evidence to connect the Dasyus-Nisadas-Bhils with the Burusos; rather, I may have classified some people as Dardic who spoke Burusaski in epic times. 5

Hodgson published his Kusunda vocabulary with some Tibeto-Burmic and Indie vocabularies 6 without any comment and the distinctive type of the language has remained unnoticed ever since. The geographical

1 In Burusaski, a = u in Eng. but.

2 Lw, loan word.

3 Mundic ipll.

4 See "sun" above.

5 Burusaski has been very fully recorded by D(avid) L(ockhart) R(obertson) Lorrimer, The Burushaski Language (Oslo, 19351938), 3 vols. (Institutet for Sammenlignende Kulturforskning, serieB: Skrifter, Vol. 19, pts. 1 3).

6 B(rian H(oughton) Hodgson, "Comparative Vocabulary of the Broken Tribes of Nepal," JASB 26 (1857), 317-332 (Kusunda, pp. 327ff.). position of the Kusundas and that of the Barbaras of the Mahabharata coincide, as nearly as we can tell, and I have identified them here. 1

Sten Konow inserted a Nahali vocabulary and text among the Mundic languages in volume 4 of the Linguistic Survey of India, thinking that the base of the language was probably a Mundic language similar to Kurku. Here, as sometimes elsewhere, Konow was influenced by geo- graphical propinquity. In an analysis of the available data I found that the base of the language was not Kurku and not even Mundic. 2

James M.Campbell in 1880 stated that the Nahals lived on the north side of the Satpudas (i.e., Satpuras), bordering on Holkar's Nimar and in the towns of Balvadi, Palasner, and Sindva, and in smaller numbers in Chirmira and Virvada. 3 Two years later Horatio Bickerstaffe Rowney 4 stated that the Nahals inhabited the northeast part of Khan- desh from Arrawad" (i.e., Adavad?) to Burhanpur. The latter is just across the border in Nimar.

Where Rowney placed the Nahals would be quite within the Bhil territory on Konow 's map. 5 Campbell said the Nahals were "the most savage of the Bhils" and he described them as very dark, small, and harsh featured. Rowney also classed the Nahals as Bhils.

The probability, then, is that Nahali is the remains of the Bhilla language 6 , the speakers of which G. S. Ghurye placed racially in his pre-Dravida type that he considered once to have occupied much of India. 7

1 Sanskrit seems to have had originally no general term for foreigner. But as the Dasa, Dasyu, Barbara, and Mleccha became more or less absorbed in Aryan civilization and the original specific meaning of these terms was no longer remem- bered, these words came to be used for any foreigner. Thus Barbara did not ori- ginally refer to any foreigner somewhat as in Greek but to a people who lived near the Kiratas.

2 * 'Nahali, a Linguistic Study in Paleoethnography," Harvard Journ. Asiatic Studies 5 (1941), 346-371.

8 Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, Vol. 12, Khandesh (Bombay, 1880), p. 94.

4 The Wild Tribes of India (London, 1882), p. 31.

5 Linguistic Survey of India, Vol. 9, pt. 3 (Calcutta, 1907).

6 In 1827 Sir John Malcolm wrote that an intelligent Bhil had assured him that some Satpura Bhils had a language peculiar to themselves ("Essay on the Bhills," Transactions RAS 1 [London, 1827], p. 81 n.).

7 Caste and Race in India (New York, 1932). There is nothing in W. Koppers work "Zum Rassen- und Sprachen-Problem in Indien," Die Sprache I (Vienna, 1949), pp. 217 234, or Die Bhil in Zentralindien (Vienna, 1948) to indicate that he noticed a physical difference between the Bhils and the Nahals, but he does remark that, although he is not a specialist in the field of physical anthropology, he has noticed not inconsiderable differences between the Bhil and Kurku, and between the Bhil and the Gond (and Baiga) (pp. 233 234 of the article). Un- fortunately the anthropometric data collected by Koppers on the jungle tribes of central India has not yet been published. Nahali vocabulary and grammar had already borrowed much from Dravidian, Indie, and Mundic when Konow published the vocabulary and text of the language, and he wrote that it was then spoken mostly by scattered families of hereditary watchmen in Nimar, so that even this somewhat corrupted language seemed on the way toward extinction. I suggested that Nahali should be more fully recorded before it entirely disappears, but the suggestion does not seem to have been followed, perhaps because the native words were buried among a mass of loan words in following the editor's suggestion to arrange the vocabulary alphabetically to make it more accessible. In the brief vocabulary of Nahali given above all words that are certainly loans have been eliminated, so that the native words will stand out clearly. If Nahali is not recorded promptly, we shall never know the language, probably once spoken over much of western India, well enough to solve problems of race and topo- nymy satisfactorily.

Early Inhabitants of the Ganges Valley

If the dwarfish, snub-nosed, black-faced Bhils occupied western India, who occupied the Ganges-Yamuna before the Aryans came? Although so little work has been done on the geographical names of India, these names may be suggestive. Hans Krahe found, in a study of the names of the Main and its tributaries, that the larger streams had received their names in pre-German times and had retained them. 1 So it is significant for our study that for the names of the three principal rivers in northern India today, Sindhu, Gangd, and Yamuna, no satis- factory etymological explanation has been found. 2 We are concerned here only with the Ganga, on the lower reaches of which were the king- doms of Anga, Variga, and Kalinga, regarded in the Mahabharata as Mleccha. Now the non- Aryan people that today live closest to the terri- tory formerly occupied by these ancient kingdoms are Tibeto-Burmans of the Baric branch. 3 One of the languages of that branch is called Mech, a term given to them by their Hindu neighbors. The Mech live partly in Bengal and partly in Assam. B(runo) Lieblich remarked the

1 "Ortsnamen als Goschichtsquelle," Schriften der Universitdt Heidelberg, Heft 4, p. 166.

2 One may add that of the large Pan jab rivers no satisfactory etymology has been found for Vitasta (the Jhelum); and although atadru (the Sutlej) may be analyzed as " (flowing in) a hundred branches," the older form Sutudrl (Rgv.) is of unknown derivation. Another of the five, the Sindhu, was noted above. These and the Yamuna and Jahnu, from which one of the names of the Ganges was derived, do not look likely to be Tibeto-Burmic. Were the names Bhilla or Aratta?

8 For the easy access of the Baric people to the area occupied by these three kingdoms, see the introduction to my "Classification of the Northernmost Naga Languages," JBRS 39 (1953), 225-264. resemblance between Mleccha and Mech and that Skr. Mleccha normally became Prakrit Meccha or Mecha and that the last form is actually found in Sauraseni. 1 Sten Konow thought Mech probably a corruption of Mleccha.* I do not believe that the people of the ancient kingdoms of Anga, Vanga, and Kalinga were precisely of the same stock as the modern Mech, but rather that they and the modern Mech spoke languages of the Baric division of Sino-Tibetan.

There are other reasons for thinking that they were Sino-Tibetans. For, although -ng- is not rare in Sanskrit, neither is it particularly common. But -n is particularly common as a final in Sino-Tibetan languages. Thus, compare the East Himalayish (Kiranti) dialect names: Radon, RuM 'en-bun, T$ in-tan Nat&eren, Walin, Yak e a, Touras,Kuluh, Tvluh, Bahin, Lohoron, Lambittfoh, Balali, San-pan, Dumi, K'alih, Dun-mali, where 12 of the 17 names end in -n.3

We may suspect that the non-Aryan names of the Ganges and of the three kingdoms at its mouth were originally Oan, An, Wan or Van, and Ka-lin or Klin ; that when the Aryan invaders took over the words they added the usual endings -a for rivers and -a for peoples ; and, although Sanskrit could have final -n, it could not have final -nd or -na and so a -g- had to be inserted. 4

Moreover Sylvain Levi 5 compared the last part of Pliny's Modo- galinga,* a people on a big island in the Ganges with Tibetan glin "island." And I have interpreted Bhujinga 7 , the name of a place which appears to have been close to Kasi and the Ganges, as from Tibetan Bod-zin "Tibetan-field, -garden."

These geographical names lead to the conclusion that a Sino-Tibetan people or peoples had pushed west and had occupied the Ganegtic valley, the richest part of Madhyadesa, before the time of the Mahabha- rata.

At the time of the Mahabharata I do not believe that the Tibeto- Burmans were an effective power in the upper Ganges valley; and the Bhils were no longer important as independent tribes in the west. This will appear below.

1 "Der Name Mleccha," ZDM012 (1918), 286-7.

2 Linguistic Survey of India 3, pt. 2, p. 1.

3 B.H.Hodgson, JASB 26 (1857), 333ff.

4 We know that archaic Tibetan had a final -nd, so it is not impossible that proto -Tibetan had a final *~ng (and *-m&) and that the name of the Ganges and the three kingdoms may have been Gang, Ang, etc. But since we have no record of such an early stage of Tibeto-Burmic, the explanation given above seems the simplest for the present, at least.

6 Pre-Aryan, pp. 102-3. Pliny VI. 18.

6 VI. 18.

7 See Geography, entry no. 28.