Art Deco: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Mumbai: Victorian and Art Deco Ensembles

The beginnings

Atul Kumar, Oct 3, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

—The writer is founder trustee, Art Deco Mumbai Trust www.artdecomumbai.com

From: Atul Kumar, Oct 3, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

From: Atul Kumar, Oct 3, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

From: Atul Kumar, Oct 3, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

From: Atul Kumar, Oct 3, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

From: Atul Kumar, Oct 3, 2019: Mumbai Mirror

Built in the 1930s, Bombay’s Art Deco buildings, one of the largest agglomerations in the world, have the unique distinction of being a ‘modern living heritage’. These are buildings that we live in and have outstanding universal value in terms of their architectural and historic significance, even though they will be 100 years old over the next decade. Bombay metamorphosed quite differently from a city like Delhi, which has defining Mughal architecture. The city's identity is born out of public and residential spaces, all of which are inhabited and in active daily use today. The story of 20th century Bombay is firmly rooted in modernism.

Art Deco exudes modernity and cosmopolitan sophistication. With a port that gave traders access to both eastern and western hemispheres, Bombay became a welcoming crucible that thrived on the latest modern styles and designs emanating from Paris in the West and Shanghai in the East. They were used by Indian architects to fulfil lifestyle aspirations of affluent merchants, who only wanted the best from the West.

The great new enablers reinforced concrete, which allowed for speedy construction at lower cost, with decorative motifs and embellishments adorning facades. Buildings came up with seemingly impossible structural variations. The construct of a cantilevered balcony that could literally ‘stick out’ with no support from below became a novel reality. Warm salubrious tropical weather led to an ingenious creation, the chajja, which covered balconies and windows. This helped provide a shelter from the rain, protection from the sun, while thoughtfully placed windows caught every breath of sea breeze to make apartments ever so comfortable with just a fan. It was a climate responsive architecture — one that adapted to weather and the environment, rather than challenging it.

Bombay owes, in a large part, its cosmopolitan lifestyle to these buildings that introduced the apartment as a living space. The city saw itself transition from community-based chawls to buildings with apartments. Neighbours, landlords and tenants engaged with curiosity. Children grew up in next door apartments forging lifelong friendships. Residents discovered and celebrated communities, festivals, foods and rituals, embracing a broad swathe of cultural and social norms that holds this city, now Mumbai, in good stead.

Celebrating the Deco men

One can hardly ignore the hallowed Brabourne stadium at the Cricket Club of India in Churchgate, designed by Pierre Avicenna d’Avoine, Partner of Gregson, Batley & King. His son, Pierre d’Avoine, himself a prominent architect in London, says his father was an avid cricketer and played for the GBK cricket team in 1929. He wielded a strong bat and turned a mean arm, taking seven wickets for 23 runs against the Barnes school, Deolali. Profession and passion melded together to reflect in the design of the stadium he built. It affords every viewer a rare intimacy with the cricket match, no matter where you are seated. Sculpted by NG Pansare, the life-size bas relief elements on New India Assurance building, Fort, designed by Master, Sathe & Bhuta, fused swadeshi elements with Deco stone clad buildings. His son, Kiran Pansare proudly shows off a photo of himself working on the majestic statue of Shiva ji that his father sculpted in bronze and installed at Shiva ji Park in 1966.

Serena Vora, now settled in California, is the great granddaughter of Maganlal Vora, of Suvernpatki & Vora, architects of iconic Soona Mahal, which stands as the most iconic façade in Marine Drive’s Art Deco precinct and host to the sea-facing restaurant, Pizza By The Bay. It was 81 years later, in 2018, that Serena discovered that her illustrious great grandfather was behind one of Bombay’s grandest Deco structure. Meher Mehta still has memories of her dashing maternal grandfather, architect Sohrabji Bhedwar, who Bombay knows of because of the red Agra stone clad Eros cinema, a magnificent V-shaped tribute to the ziggurat.

If architect FW Stevens is famous for CSMT (VT Station), then the city owes no less a debt of gratitude to his son Charles Stevens for designing Regal Cinema, Bombay’s first Art Deco building, a landmark with air-conditioning, underground parking, neon lighting and, in a thoughtfulness way ahead of its time, limited seating with aids for the hearing impaired.

The June 2018 inscription of the ‘Victorian Gothic and Art Deco Ensembles of Bombay’ as a UNESCO World Heritage site celebrates the city’s modern living heritage. The inscription affords a layer of protection to 76 Art Deco buildings in South Bombay. It will largely be the city’s consciousness that has to keep this rich legacy alive for future generations. We remain accountable to them. If we let them down, they will certainly not look at us kindly.

Across the length and breadth'

Bombay’s Deco embraces both typologies and the city’s geographical expanse, creating an emotional quotient for Bombayites, since it is a city built largely by its residents and many of its public buildings were gifts of philanthropy. These buildings are treasure troves of history and endearing stories. Several generations have studied at Don Bosco High School in Matunga. In the Fort district, the first insurance policy available to Indians came from swadeshi firms such as Lakshmi Insurance (1938) and New India Assurance (1937), both designed by Master, Sathe & Bhuta.'

A generation remembers seeing 007 Sean Connery in Goldfinger, in 1964, at Regal Cinema. In 2006, a new generation thronged to catch 007 Daniel Craig in Casino Royale. Regal still holds its own across generations. Late Nazir Hoosein, the owner of Liberty cinema, a Deco showplace of the nation, narrates how artist MF Husain danced barefoot every evening in the aisles of Liberty cinema, throwing coins at the screen, captivated by Madhuri Dixit, dancing in Hum Aapke Hain Kaun.

Liberty was designed by MA Riddley-Abbot, in 1949. The Udwadia family healed the city’s elite at Breach Candy Hospital, one of the many buildings designed by Gregson, Batley & King, who Prof Mustansir Dalvi of Sir JJ College of Architecture identifies as “the largest practice, amongst the Bombay architects during the 1930s and the 1940s”. Maithili Ahluwalia who created an epochal concept store, Bungalow Eight, often heads to catch a conversation over a drink at West End Hotel’s chic deco bar Chez Nous, saying, “it’s a rewind where she loves to unwind”. Built on the philosophy “a hotel is meant to be a home away from home”, this hidden jewel was built in 1948.

Deco’s geographical breadth spreads across Bombay. Its landmarks define neighbourhoods. Matunga has cafe Koolar & Co, while Aurora cinema, by Marathe and Kulkarni, fed a different nutrient, the best of Rajnikanth to a largely South Indian community. Vile Parle has Nanavati Hospital, while Chowpatty boasts of Ideal Café at Phoolchand Nivas. Deco bungalows in Juhu and Chembur still hold their own against the onslaught of high rises affording the area a quality of life you can’t find today. With its majestic sweep of 35 Deco buildings, Marine Drive remains Bombay’s pre-eminent public open space that is an affirmation of diversity, harmoniously bringing together people of all cultures, age groups and ethnicity. Oval Maidan straddles two centuries of architecture.

Bombay’s place on the global map is secure. It hosts the second largest collection of Art Deco buildings in the world, 552 to be precise, and we are still counting. Matunga, not South Bombay’s Marine Drive holds pride of place as the single largest Deco neighbourhood. Last year, the International Coalition of Art Deco Societies took cognisance of Bombay’s Art Deco by making it a member of this prestigious international body – a recognition that belongs first to the city.

As of 2025

Mohua Das & Sneha Bhura, TNN, May 18, 2025: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das & Sneha Bhura, TNN, May 18, 2025: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das & Sneha Bhura, TNN, May 18, 2025: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das & Sneha Bhura, TNN, May 18, 2025: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das & Sneha Bhura, TNN, May 18, 2025: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das & Sneha Bhura, TNN, May 18, 2025: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das & Sneha Bhura, TNN, May 18, 2025: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das & Sneha Bhura, TNN, May 18, 2025: The Times of India

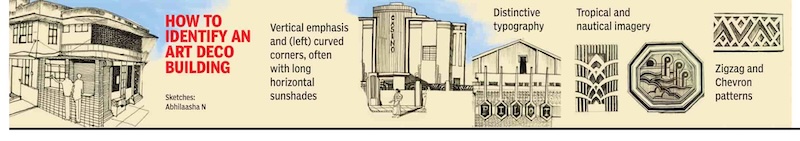

A hundred years ago, Paris hosted the 1925 Exposition that gave Art Deco its name. The movement would captivate the world. Its language — sunbursts, zigzags, a blend of lavish curves with sharp symmetry, ancient motifs with modern materials — turned architecture into theatre. Unlike past styles that clung to tradition, Deco was restless. It travelled fast and shapeshifted easily, absorbing local flavours from Madras to Mumbai. On its centenary, a look at this iconic aesthetic...

IN MUMBAI, A GLOBAL STYLE GETS A LOCAL AVATAR

Few cities have worn the style quite like Mumbai, with the aesthetic shaping the city’s skyline in a way that has lasted well beyond its initial boom. In fact, Mumbai is home to the world’s second-largest collection of Art Deco buildings after Miami. But how did this architectural movement take root here and why does it still hold such sway? One big reason is that it stayed true to global design principles while adapting to the city’s pulse. In cities like Paris and New York, Art Deco was all about luxury — marble, chrome, and glass — but in Mumbai, the materials used were sturdier like concrete, stone, and tiles, while the wide verandas, open balconies and airy spaces were designed to battle heat and humidity. Mustansir Dalvi, architect and trustee of Art Deco Mumbai Trust (ADMT) that has been documenting and advocating for this legacy since 2016, says, “The design wasn’t just for show but practical, to make life easier.” Architect Claude Batley, he adds, described them simply as ‘this new architecture’.

That ‘new architecture’ entered Bombay’s shores through multiple doors — cinema halls, community centres, residential buildings on newly reclaimed swamp land. These semi-circular buildings with sweeping curved balconies seemed to float above the street, with distinctive features like sunrise and wave motifs worked into wrought iron grilles and gates, porthole windows and vertical bands of glazed windows that lit up stairwells. “They were in sharp contrast to the dominant British neoclassicism of the time in colonial cities,” Dalvi points out.

The tide of time and redevelopment has claimed many of these structures over the years. The latest casualty may be Khar Municipal Market, the city’s only known Art Deco public market facing possible demolition. But across neighbourhoods — from Vile Parle to Matunga — some residents, architects and conservationists are pushing back with community-led restoration efforts to save what they can, before it’s too late.

Metro Cinema in Dhobitalao, built in 1938 by Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM) as part of their expansion into the Indian film market, was restored to its former Art Deco glory in 2016. Eros Cinema with its curved lines and red sandstone V-shaped facade reopened last year with its heritage structure restored. For Dalvi, the fight isn’t just about nostalgia. “It’s about preserving not just buildings but neighbourhoods. These buildings all work together in some sort of an urban harmony,” he says. “And if you change the profile, height and the shape of any one building, the entire neighborhood loses its essential spirit, which is unfortunately happening in many places now.”

While Marine Drive and the Oval Maidan often steal the spotlight, the style took root in unlikely corners too. Take the Sumati Maternity Home (1945) in Vile Parle founded by Dr Chhaya Hindlekar in the post-war years. Tucked inside the unassuming Sumichha building, it brought Deco elegance to women’s healthcare in the suburbs. In Matunga, Kerala Bhavanam, built in 1958 by the Bombay Keraleeya Samaj, became a gathering point for Malayalis during Onam and other festivals. Dadar’s Sugat Niwas, with its curved balconies, frieze bands, and quiet red facade, is easy to miss but hard to forget.

In Sion, Vishwa building stands tall with its stupa domes, decorative brackets and clean modern lines — a textbook case of ‘Indo-Deco’ which, according toUnesco, is: Western in form but Indian in spirit. Dadar’s Gayatri Nilayam looks like a ship docked on land with its marine-inspired fish motifs, porthole windows and ship-like curved balconies. But what makes it radical is that it was among the first to bring toilets into the home with ‘self-contained’ flats that upended caste-driven ideas of purity and pollution. In a city where so much is being torn down, Karfule in Ballard Estate is Mumbai’s only surviving Art Deco petrol pump, and a great example of how the design touched even the most everyday spaces. Built in 1938 by architect Gajanan B Mhatre, it has an octagonal kiosk, a long concrete canopy that seems to float overhead and a tall central tower — all classic Deco features. Inside, the star-shaped terrazzo flooring and brass grilles have been carefully preserved by the Sequeira family, who still run the station, In 2018, they hosted an exhibition with archival photos, original drawings, and vintage memorabilia for Karfule’s 80th anniversary to keep the pump’s legacy alive.

Dalvi warns that only a small fraction of the city’s Deco buildings are protected. “The only safe buildings are those that have the Unesco tag,” he points out. “Redevelopment can take place in any of the other buildings or neighbourhoods.” The only real defence, he believes, is awareness: “When people themselves understand that they are living in something special, they will protect it. As, in fact, happened with the Oval Maidan where citizens rallied to save the precinct. We need more such localised citizen-based initiatives.”

ADMT, which was founded by Atul Kumar in 2019, has also been guiding residents through restoration projects and offering archival and aesthetic expertise. Till date, the trust has documented 1,477 Art Deco buildings across Mumbai. “If you don’t know what you have, how can you preserve it or assign value to it?” says Kumar. When people themselves special, they will protect.

Their repair and restoration practice has assisted around 15 projects. “Some want just the original Art Deco lettering restored. Others find old photos and ask us to help bring back colour palettes from the 1930s. And then there are the full-scale facelifts,” says Kumar. Their interdisciplinary team includes conservation architects, historians, researchers and outreach specialists.

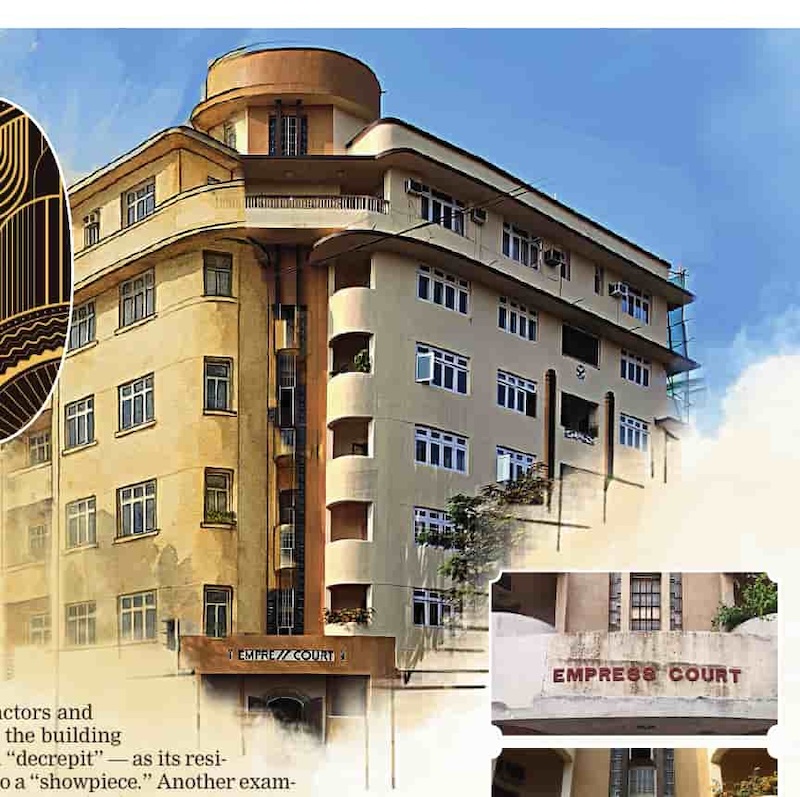

One standout success is Swastik Court, a five-storey Deco apartment from the 1930s near Oval Maidan. By 2019, it had fallen into disrepair. But in a rare collaboration between landlords, residents, contractors and the ADMT team, the building was revived from “decrepit” — as its residents put it — into a “showpiece.” Another example is Empress Court, a majestic 1936 structure on a corner plot along the Oval, where residents worked with the trust to restore its original name lettering.

“We’re seeing what I call the third pivot,” says Kumar. “People are now saying they don’t want to lose their property to redevelopment. They’re asking if they can grade their building as heritage.” Policy, however, remains a stumbling block. “So, the colonial buildings all get listed quite easily. But these buildings are relatively young and have been in constant use so it’s not easy to get heritage protection. That needs to be re-looked at,” says Dalvi. Beyond heritage status, there’s also the economic pressure to rebuild.

It’s not the same thing, but Kumar observes that Deco design is enjoying a quieter resurgence, be it in the lobbies of multiplexes or high-end developments in Worli. “We’re getting proposals now from developers who want to theme their projects around Art Deco,” he says. “There’s definitely a resurgence but in a different avatar.”

MAPPING DELHI’S HIDDEN 'EYEBROW' MARVELS

Can buildings have eyebrows and eyelids? In Art Deco architecture, eyebrows are overhangs or 'chhajas' above windows and balconies that shield the interior from sun and rain. 'Eyelids' are sweeping canopies or projecting roofs that lend entrances a theatrical flair. A 2023 pocket guide map of Delhi’s Art Deco buildings illustrates these features through hand-drawn details, mapping 20 examples — from St Stephen’s College and Dholpur House to Safdarjung Airport and Delite Cinema’s tripartite elevation.

The map is the handiwork of DecoInDelhi, a digital archive created by arts researchers Geetanjali Sayal and Prashansa Sachdeva. When they began documenting Delhi’s urban heritage in 2020, Art Deco wasn’t their focus. But walking through Daryaganj and Chandni Chowk, they began noticing streamlined balconies, porthole windows and stylised grills. They later realised they had uncovered a scattered, little-known substrata of Art Deco in the capital, hidden in plain sight.

Most people associate Delhi with grand Mughal, neoclassical and modern brutalist landmarks. “But Art Deco flourished wherever ordinary citizens had agency. It’s the quiet antithesis to what was officially imposed,” says Sayal.

“Pusa Road, in particular, became a street where Art Deco buildings came through a mix of Delhi Improvement Trust (DIT, which was a predecessor of DDA) projects and private commissions. Architects from DIT were Anglo-Indians or of mixed ethnicities so they had exposure to the style,” adds Sayal. With a grant from the India Foundation for the Arts, DecoInDelhi’s work has expanded into documentation, photographer collaborations, archival work with backstories about the buildings, architects, homeowners etc, and a glossary (including signage typography).

Sayal says the current focus is working with homeowners. “For instance, someone whose house we documented earlier on Pusa Road is now collaborating with us to tell the story of her Deco-style maternal home which was demolished.”

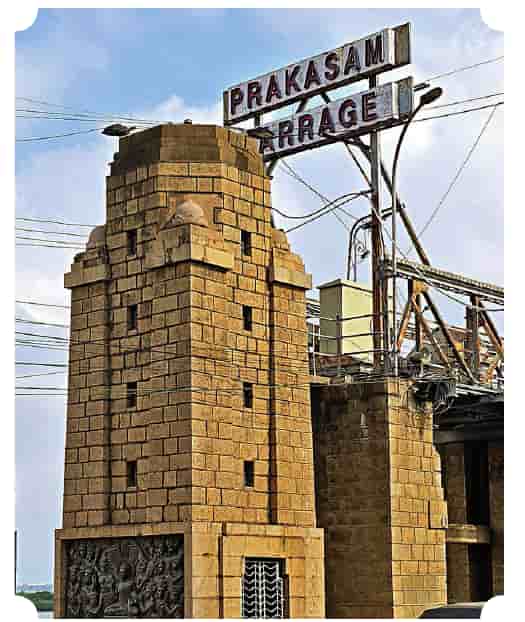

HYDERABAD’S MULTICULTURAL HISTORY DECO-DED

In the 1930s, Austrian architect Karl Malte von Heinz, a refugee from Nazi Germany where Hitler’s regime was cracking down on the Bauhaus movement, introduced Art Deco to Hyderabad. He was invited by Raja Ram Rao of Wanaparthy to design a house in Banjara Hills, later known as Mount Pleasant and now part of Muffakham Jah College. Architects like Mohammed Fayazuddin and Eric Marrett later helped popularise the style across the city. Marett also designed the Raj Bhavan (then the Governor’s residence), which recently became the fitting location for kickstart ing celebrations to mark 100 years of Art Deco.

Architect Srinivas Murthy, founding president of Architecture & Design Foundation India (ADFI), has led extensive documentation of the style. “We’ve now documented 148 key Art Deco buildings in Hyderabad of which around 60% are private residences,” he says. “Hyderabad’s Deco is unique because of its multicultural roots. You find Hindu, Islamic, Buddhist, and European architectural influences fused into Deco forms. Few other cities have this layered expression... Many Deco homes are perched on hills or near these ancient granite formations, which makes the buildings especially interesting and construction quite challenging.”

But like in several other Indian cities, it’s a struggle to save these structures. “Since these buildings aren’t protected by law, they can legally be demolished. In the past 4-5 years, 12-15 Deco buildings in Hyderabad have been lost,” says Murthy. “It is ironic that while the whole world is celebrating 100 years of Art Deco, a landmark like Secunderabad railway station was demolished earlier this year. That’s why we’re urging for more awareness campaigns and incentives for owners," says Murthy. He led Hyderabad’s first Art Deco walk on April 29 through Secunderabad’s Jeera Colony, with stops at Rashtrapati Road and Monda Market, home to the twin cities’ Art Deco-style clock tower.

Murthy has tracked Deco across India. “We’ve found structures in Punjab, Kerala, Goa, even in rural and semi-rural stretches. In Kerala and Goa, you see ‘Tropical Art Deco’ with sloping roofs. In cities like Hyderabad or Patiala, the Deco style is closer to its original geometric form. Each place has absorbed and interpreted it in its own way.”

IN CHENNAI, REVIVAL BEGINS WITH MEMORIES

Chennai, once rich in Art Deco architecture, has lost many of its gems to redevelopment — among them, the iconic Dasaprakash Hotel in Egmore, known for its porthole windows and wood-paneled interiors. But today, a new generation is attempting to rediscover this legacy. Artist Abhilaasha N and architect-turned-writer Archita S recently held a sketching workshop to mark 100 years of Art Deco. “In the 100th year of Art Deco, this felt like a fitting way to introduce people to the style,” says Archita. Using archival photographs, participants drew the original facade of Casino Theatre, which used to be one of Chennai’s finest Deco cinemas but its renovated avatar bears no trace of its Art Deco roots.

Prathyaksha Krishna Prasad, founder of Art Deco Madras and The Heritage Art Collective, has given many talks on Chennai’s Deco history and is now curating a Deco-specific walk. “If I had limitless resources, I’d have conserved the Dasaprakash Hotel,” she says. “But my dream is to create a dedicated Deco museum that captures not just the architecture, but life in 1920s Madras.”

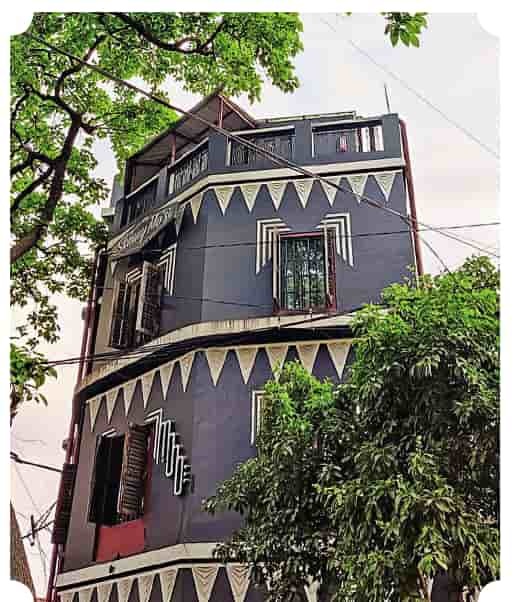

KOLKATA’S METRO-STYLE BARI GET NEW LIFE AS CAFES, BOUTIQUES

Kolkata’s Art Deco is more domestic and personal rather than institutional. “What’s unique here is how the middle class adapted Art Deco,” says writer and former MP Jawhar Sircar, who has led public walks and tours through South Kolkata. The Calcutta Improvement Trust’s redevelopment schemes in the 1930s set the stage for this architectural flowering.

“Around the 1950s, the corporation didn’t require an architect’s signature for house plans. People could simply hire masons and build,” says Sircar. And build they did — across Hindustan Park, Southern Avenue, Keyatala, Lake Road and New Alipore. It was often the women of the house who directed the design. “They’d call the mason and say, ‘Metro bari chaai’. That meant they wanted geometric lines, a breeze-catching frontage and a circular veranda.” These homes have proven surprisingly resilient. “Almost all of them [are] still standing. That’s the most heartening part.” In fact, they’ve found new life — as boutique cafés and designer stores and even modern jazz clubs that use the signage style. “It’s young people running these cafés in Art Deco homes. Menus are experimental. The vibe is youthful. When I walk in, they look at me like I’ve walked in from another era,” says Sircar. From the ‘jahaj bari’ (ship-shaped houses) of Elgin Road to hundreds of homes documented by Instagram accounts like Calcutta Art Deco and Calcutta Houses, the city’s democratic embrace of the style is finally being seen. If he could, he says, he would advocate for an official Art Deco district that spans Alipore, New Alipore and Rashbehari Avenue.

Writer Amit Chaudhuri also helped bring attention to Kolkata’s Art Deco in 2015 with an essay in The Guardian that led to the formation of Calcutta Architectural Legacies (CAL). “I think Calcutta has — along with Bombay — among the greatest number of Art Deco buildings in the world,” he says. That year, he joined INTACH in a PIL against the demolition of Roxy Cinema, a historic Art Deco structure, now being restored after a successful campaign. CAL and INTACH are also working to save the Lake Temple Road cluster, a well-known pocket of Art Deco residences in South Kolkata.

But things move slowly,” admits Chaudhuri whose first novel, ‘A Strange and Sublime Address’, was about a Calcutta house that was “magical in its ordinariness”. He says the civic body needs to recognise that Art Deco often defines neighbourhoods, not individual landmarks.

2018: Unesco World Heritage status

HIGHLIGHTS

The feat makes Mumbai the second city in India after Ahmedabad to be inscribed on the World Heritage List.

This inscription gives Mumbai the distinction of having three Unesco World Heritage Sites (Elephanta, Chhatrapati Shiva-ji Maharaj Terminus and the Victorian & Art Deco Ensembles).

It was a euphoric day for Mumbai on Saturday. Fourteen years after the idea was first mooted, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) finally declared the city’s Victorian and Art Deco Ensembles, straddling two heritage precincts of Fort and Marine Drive, a World Heritage Site.

The feat makes Mumbai the second city in India after Ahmedabad to be inscribed on the World Heritage List.

The announcement from Bahrain, where the Unesco World Heritage Committee meeting was held, came around 1pm when conservation architect Abha Narain Lambah, part of the Indian delegation, sent a message to TOI: “Mumbai’s Victorian and Art Deco Ensembles inscribed as a Unesco World Heritage Site.” CM Devendra Fadnavis, who had endorsed Mumbai’s nomination, said: “This is a huge victory for Mumbai.”

“We are very happy. Mumbai has always been a world city, now it’s got another Unesco heritage site,” CM Fadnavis said.

TOI was the first to report on May 5, 2018, that Unesco’s Paris-based technical adviser had recommended the prestigious tag for the enclave.

The latest inscription gives Mumbai the distinction of having three Unesco Sites, alongside Elephanta and CSMT. Maharashtra leads the states with five Unesco tags (including Ajanta and Ellora). India now has 37 World Heritage inscriptions in all.

The city’s 19th century collection of Victorian structures and 20th century Art Deco buildings includes the row of public buildings of the High Court, Mumbai University, Old Secretariat, NGMA, Elphinstone College, David Sassoon Library, Chhatrapati Shiva-ji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Western Railways headquarters, Maharashtra Police headquarters to the east of Oval Maidan and the Art Deco buildings consisting of the first row of Backbay Reclamation scheme, buildings such as the Cricket Club of India and Ram Mahal along Dinshaw Wacha Road, the iconic cinema halls of Eros and Regal and the first row of buildings along Marine Drive.

The eastern edge of the property is defined by Mahatma Gandhi Marg and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Chowk within the designated historic precinct of Fort area. This marks the edge of the 19th century fortified city of Bombay (now Mumbai). Though the fort walls were mostly torn down in the 1860s under the governorship of Sir Bartle Frere, the name persists in public memory and is a protected heritage precinct under the Heritage Regulations for Greater Bombay 1995.

The western edge of the property is defined by the Arabian sea that lines the 20th century Art Deco buildings of Backbay Reclamation and Marine Drive. The northern edge of the property is defined by Veer Nariman Road and the southern edge by Madame Cama Road.

TOI was the first to report on May 5, 2018 that Unesco’s technical adviser, the Paris-based International Council of Monuments and Sites (Icomos), had recommended the prestigious tag for the landmark south Mumbai enclave. Once Icomos gives its stamp of approval to a proposal, it is generally accepted by Unesco.

Lambah, who prepared the nomination dossier, said, “From 2004, when I first presented this idea at the Unesco conference on representation at Chandigarh, it’s been 14 long years to get all stakeholders, citizen groups and government on board to make this happen. This inscription acknowledges Mumbai’s position in the world as the finest collection of 19th and 20th century modernism; a city where heritage does not just include dead monuments but a living, breathing, dynamic urban centre with buildings in active use by citizens. This is the first case in India’s 37 world heritage sites where the nomination process was a citizen-driven initiative.”

The idea found resonance with local citizen groups: UDRI, Kala Ghoda Association, Oval Cooperage Residents Association, OVAL Trust, Nariman Point-Churchgate Citizens Association, Heritage Mile Association, Federation of Residents’ Trusts, Observer Research Foundation as well as the MMR Heritage Conservation Society. It was also endorsed by eminent Mumbaikars such as Amitabh Bachchan, Fadnavis and Shaina NC, who wrote to the Central government endorsing this nomination.

Lauding this effort as a unique partnership among citizens and government bodies in making this nomination successful, Shirin Bharucha and Nayana Kathpalia representing the various civic groups and NGOs said, “It recognizes the value of the unique Victorian Gothic and Art Deco architecture to the urban form, history and soul of a city.”

Atul Kumar of Nariman Point-Churchgate Citizens Association said, “Stakeholders and residents are delighted to celebrate a historic and milestone moment in the history of Mumbai’s Victorian and Art Deco architecture and thank the state government and Indian government for this initiative.”

The nomination dossier was submitted by the state government to the Ministry of Culture in 2014 and it was endorsed by Fadnavis. In January 2015, the CM wrote to the Centre urging it to send Mumbai’s nomination as India’s official entry to Unesco. “Mumbai’s tourism and culture would be hugely benefited if this nomination succeeds. Mumbai will be brought on the international tourist map. Being the financial capital of our country, Mumbai attracts many businessmen like London and some European cities. It would have the unique distinction of being both a financial capital and a world heritage site,” he had said.

Conservation architect Vikas Dilawari, while calling this a proud moment for the city, said the Victorian Ensemble selected and nominated was minimal. “The Fort area has much more to offer like all other public buildings facing Cross Maidan and Azad Maidan, DN Road etc. Hopefully these will be included in the next phase, just as how it started with one building — CSMT — in 2004 and has now reached an ensemble scale.”