Battle of Bhima- Koregaon: 1818

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The authors of this article

Sources:

1. Shoumojit Banerjee, January 1, 2018: The Hindu

2. January 3, 2018: The Economic Times

3. January 3, 2018: The Economic Times

4. Shreya Biswas, January 2, 2018: India Today

5. Zeeshan Shaikh, January 4, 2018: The Indian Express

6. Rumu Banerjee, Koregaon Bhima: One war, varied versions, January 9, 2018: The Times of India

The battle: January 1, 1818

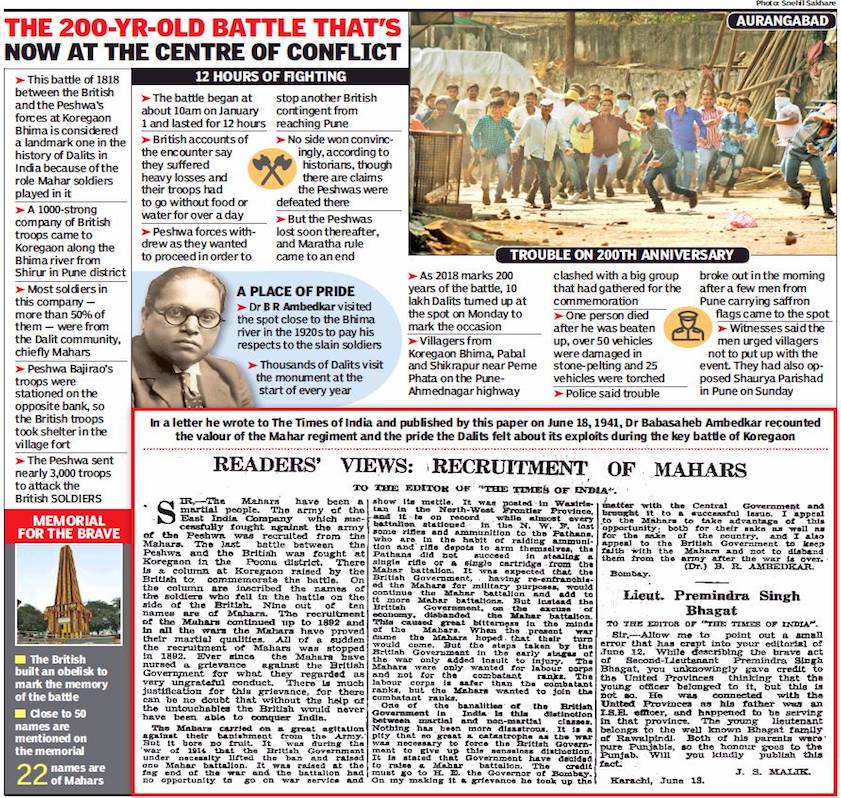

It was the last battle of the Anglo-Maratha war fought at Koregaon on the banks of Bhima river, hence the name Bhima Koregaon battle, on January 1, 1818 between the British East India Company and the Peshwa faction of the Maratha Confederacy. Peshwa Baji Rao II, defeated in the Battle of Khadki near Pune on 5 November 1817, hotly pursued by the Company forces, turned towards Pune. On his way, he ran into an 800-strong Company force. The Peshwa sent around 2,000 soldiers to attack the Company forces, turned towards Pune. On his way, he ran into an 800-strong Company force. The Peshwa sent around 2,000 soldiers to attack the Company force led by Captain Francis Staunton. The Company troops fought for the whole day, forcing Peshwa's troops to withdrew because they feared Company reinforcements.

A brief history

The Battle of Koregaon (aka Koregaon-Bhima battle, or Bhima-Koregaon battle) was fought between the British East India Company and the Peshwas army at Koregaon Bhima on January 1, 1818.

Legend has it that about 500 Mahar soldiers under the East India Company clashed with a 25,000-strong army of Peshwa Bajirao II.

Mahars, at this point, were considered an Untouchable community, and were not recruited in the army by the Peshwas.

Despite this, as per the Dalit version of the Koregaon-Bhima battle, Mahars approached Peshwa Bajirao II to let them join his army against the British. Their offer was turned down. That is when the Mahars approached the British, who welcomed them into their army.

The Battle of Koregaon ended with the British-led Mahar soldiers defeating the Peshwas. The victory was not just of a battle for the Mahars, but a win against caste-based discrimination and oppression itself.

In 1851, the British erected a memorial pillar at Koregaon-Bhima to honour the soldiers -- mostly Mahars -- who had died in this battle. On January 1, 1927, Bhimrao Ambedkar started the ritual of holding a commemoration at the site of this pillar, one that is repeated every year.

The battle took place at the village of Koregaon (population 960) 16 miles northeast of Pune, where 800 British troops faced 30,000 Marathas on January 1, 1818.

The story of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon on January 1, 1818 has come to be mediated by competing narratives of Dalit assertion against Brahminical oppression, and Indian ‘nationalism’ standing up to the colonial army of the East India Company. Dr B R Ambedkar visited the Jaystambh repeatedly, and said in a speech in Sinnar in 1941 that the Mahars had defeated the Peshwas at Koregaon. Despite British claims of having achieved “one of its proudest triumphs”, the outcome of the battle remains contested, and some Maratha histories have claimed it was the Peshwa army that was, in fact, victorious.

One of the earliest accounts of the battle was published in 1885 in the three-volume The Poona District Gazetteer, edited by James M Campbell, ICS, as part of the series of Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency. This is what the Gazette recorded.

The battle took place at the village of Koregaon (population 960) 16 miles northeast of Pune, where 800 British troops faced 30,000 Marathas on January 1, 1818. Six months earlier, on June 13, 1817, Peshwa Bajirao II had been forced to cede large swathes of territory to the Company, officially ending the Maratha Confederacy. In November, the Peshwa’s army revolted against the British Resident at Pune, but was defeated in the Battle of Khadki. Pune was placed under Colonel Charles Barton Burr. At the end of December, Burr received intelligence that Bajirao intended to attack Poona, and requested help. The second battalion of the first regiment Bombay Native Infantry of 500 rank and file under Captain Francis Staunton, accompanied by 300 irregular horse and two six-pounder guns manned by 24 European Madras artillerymen, left Sirur for Poona at 8 pm on December 31, 1817. After marching 25 miles, about 10 the following morning, they came across the Bhima river the Peshwa’s army of 25,000 Maratha horse. The Gazette does not mention the caste of Indian soldiers in Staunton’s army, but later accounts say a sizeable number were Mahars.

The MARATHAS recalled a body of 5,000 infantry that had proceeded some distance ahead, the Gazette records. Three parties of 600 each — Arabs, Gosavis and regular infantry — supported by two guns, then besieged the British troops. Cut off from water and food, and after losing one of their artillery guns, some British troops were keen to surrender. However, the six-foot, seven-inch Lieutenant Pattinson led a counterattack to take back the artillery gun from the Peshwa’s Arab soldiers. Fierce fighting followed and, “as night fell”, the Gazette records, “the attack lightened and they (the British) got water. By 9 the firing ceased and the Marathas left”. Of the 834 British troops, 275 were killed, wounded, or missing. The Marathas lost between 500 and 600 killed and wounded. Subsequently, as Maratha strongholds started falling, Bajirao II went on the run, finally surrendering in 1823. The British kept him in Bithur until his death in 1851. His successor, Nanasaheb Peshwa, was the last of the titular heads of the Peshwai system.

Different narratives to the battle

A symbol of Dalit pride?

The battle has come to be seen as a symbol of Dalit pride because a large number of soldiers in the Company force were the Mahar Dalits. Since the Peshwas, who were Brahmins, were seen as oppressors of Dalits, the victory of the Mahar soldiers over the the Peshwa force is seen as Dalit assertion.

Dalit Matangs Fought For Peshwa: Scholar

There is more than one narrative to the legacy of the Koregaon Bhima battle as while Dalit Mahars fought as part of the British force, another Dalit community —Matangs—were represented in the Peshwa army in the politicised clash of arms that took place in 1818, said Abhinav Prakash, an assistant professor in Delhi University.

Prakash, a Dalit scholar, spoke of what he said were distortions and exaggerations in the accounts of the Koregaon Bhima war in the context of claims that the battle signified a caste assertion by Mahars against Brahminical oppression. These were attempts to push a Dalit-Brahmin divide, said Prakash who spoke at a function organised by BJP think tank S P Mukherjee Research Foundation on Saturday.

An agenda-driven account was being peddled, as according to Prakash, the celebrations of Koregaon Bhima were never a British commemoration, but have been projected as a recognition of Dalit valour and courage. “The Mahars fighting for the British against the Peshwas as a fight against caste oppression is a fallacy…another Dalit community, the Matangs, also fought, but in the Peshwa army. So whose narrative is the Dalit narrative?” asked Prakash, questioning the depiction of the battle as a Dalit versus upper caste affair.

“There’s a complete absence of Dalit and tribal history from mainstream history being taught today. The fact is that caste history, though anathema to the right-wing, needs to be highlighted and taught to the people,” said Prakash, adding that a failure to do so may well result in the narratives being appropriated by those who wanted to play on caste divides.

“We can’t deny the reality of caste,” he said, adding that history couldn’t be viewed through rigid orthodoxies. Stating that some of these claims are right-wing, Prakash, who teaches at Sri Ram College of Commerce, argued that they did not represent “real right-wing thinkers” but champions of orthodoxy. Prakash, who was associated with ABVP in his JNU days, describes himself as a right-wing Ambedkarite and has been vocal about appropriation of the Dalit discourse by non-Dalits.

The men who fought in the battle of Koregaon were the Mahars, and the Mahars are Untouchables. Thus, in the first battle and the last battle (1757-1818) it was the Untouchables who fought on the side of the British and helped them to conquer India." It was natural for Ambedkar to feel proud of the Mahar valour when the Mahars were considered nothing more than untouchables destined to do lowly work. Since then, a number of Dalits have commemorated the battle by visiting the memorial obelisk as a symbol of Dalit assertion against the Brahminical Peshwa forces.

The Koregaon Ranstambh (victory pillar) is an obelisk in Bhima-Koregaon village commemorating the British East India Company soldiers who fell in a battle on January 1, 1818, where the British, with just 834 infantrymen — about 500 of them from the Mahar community — and 12 officers defeated the 28,000-strong army of Peshwa Bajirao II. It was one of the last battles of the Third Anglo-Maratha War, which ended the Peshwa domination.

Role of Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar

Ambedkar’s visit to the battle site on January 1, 1927, revitalised the memory of the battle for the Dalit community, making it a rallying point and an assertion of pride. On 1 January 1927, B.R. Ambedkar visited the memorial obelisk erected on the spot which bears the names of the dead including nearly two dozen Mahar soldiers. This is what he said: "Who were these people who joined the army of the East India Company and helped the British to conquer India? ...the people who joined the Army of the East India Company were the Untouchables of India. The men who fought with Clive in the battle of Plassey were the Dusads, and the Dusads are Untouchables.

In 2005, the Bhima-Koregaon Ranstambh Seva Sangh (BKR-S-S) was formed to keep alive the memory of this episode in Indian history and pay homage to those among the Dalit community who fought for their self-respect in that battle.

From mere thousands in earlier years, today lakhs of visitors from across India come to pay homage at the site; there is a particularly massive representation of community members from Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka and Gujarat. One part of the tradition is that several retired officers of the Mahar Regiment come to do homage to this exploit of valour.

In 2018, the Elgaar (battle-cry) Parishad, an event celebrating the bicentenary of the battle irked some right-wing Hindutva and Brahmin organisations, who demanded that the city police prohibit its staging at the Shaniwarwada fort, the erstwhile seat of Peshwa power.

The Dalit–Maratha rift

Relations between the Mahars and the Peshwas, who were Brahmins, grew strained after the death of Baji Rao I in 1740, and reached their nadir during the reign of Bajirao Rao II, who insulted the Mahar community and spurned their offer of service with his army. This caused them to side with the English against the Peshwa’s numerically superior army.

Dalit scholars say Indian history is often recorded from a Brahminical perspective, which has resulted in Bhima-Koregaon and other battles in which Dalits fought, not getting their due. BKR-S-S members, though, point out the dangers of the reductive view of the battle as caste conflict, and cite historical records documenting Mahars fighting in the Maratha army since the times of Shiva-ji, and even fighting alongside the Peshwa’s forces, including in the third battle of Panipat and the battle of Kharda.

Some accounts say that Govind Ganapat Gaikwad, a Mahar, performed the final rites of Sambhaji (Shiva-ji’s son) after he was tortured to death and hacked to pieces on Aurangzeb’s orders in 1689.

What the opponents say

Ambedkar's pride in Bhima Koregaon belonged very much to that age. Ambedkar was a very original and provocative thinker. Some of his views were quite cogent but belonged to those very times. For example, many of his views on Muslims and Christians would be totally unacceptable in today's India. Second, it was not as if the British were kind to the Mahars.

In fact, the British had abolished the Mahar regiment after 1857 uprising. They started preferring upper castes whom they called 'martial races'. The Mahar regiment was restarted only during the Second World War. Third, the Peshwa soldiers who fought against the Company forces including the Mahars at Bhima Koregaon were mostly Arabs. Can those Arab soldiers be seen as fighting to save the Brahaminical regime of the Peshwas? Moreover, a lot of the Mahars too fought alongside the Peshwas. If The ompany forces were pitted against lower-caste Sikhs, would the Mahars have refused to fight against fellow Dalits? There are innumerable incidents when Hindus fought on the side of Muslim forces against Hindus. The naked naga sadhus, who belong to the Shaiva tradition of Hinduism, had fought on the side of Ahmed Shah Abdali in the Third War of Panipat against the Peshwas.

Koregaon Bhima battle

2018: the 1818 Koregaon Bhima battle's echoes

See also: Battle of Bhima- Koregaon: 1818

Radheshyam Jadhav, Fresh twist to Maha’s Dalit politics, January 3, 2018: The Times of India

From: Radheshyam Jadhav, Fresh twist to Maha’s Dalit politics, January 3, 2018: The Times of India

Backward Bloc Consolidating In Bihar-Like Pattern: Dalit Intellectuals

Maharashtra’s Dalit politics is moving in a different direction on the lines of the Triveni Sangh experiment in Bihar where the backward communities consolidated their power against upper castes, say Dalit intellectuals and activists in reaction to the developments at Koregaon Bhima on Monday.

Right-wing and Dalit historians have their own versions of the Koregaon Bhima battle. For Dalits, it was a battle against casteist Peshwa rulers, while for right-wing historians it pitted the British against indigenous rulers.

“Koregaon Bhima must be seen from two angles — the British fulfilled their agenda to gain power and the oppressed communities, comprising agricultural workers, found a way to fight oppressors,” Paul Divakar, a Dalit intellectual with the New Delhi-based National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights, said. “A Triveni Sangh is happening in Maharashtra and Koregaon Bhima developments might be a new beginning.”

Triveni Sangh was formed by Yadav-Koeri-Kurmi communities as a front to fight upper castes’ domination in Bihar in the 1930s. It changed the socio-political discourse of the region. Divakar added that as of now BJP and Shiv Sena have succeeded in getting the support of Matang and Mahar communities, respectively, while Congress is confused about its stand on caste politics. “ I don’t see these developments as against one caste. It is more than that,” Divakar added.

Dalit activists in Maharashtra said there is a vacuum in Dalit politics. “Ramdas Athavale has aligned with BJP and Prakash Ambedkar’s party has not succeeded in garnering a mass base. Jignesh Mevani and Prakash Ambedkar coming together and other backward parties joining the move is the beginning of new Dalit politics after the Dalit Panther era,” Dalit leader R S Kamble said.

The socialist and Leftist parties in Maharashtra are eager to join the bandwagon. The R-S-S leadership is cautious. R-S-S veteran from Pune, Aniruddha Deshpande, said, “It is a complicated situation. The British took control of Shaniwarwada and the Dalits were part of their army. I don’t think it is appropriate to comment on these developments.”

Supreme Court‘s Judgement, 2018 Sept

The Supreme Court refused to interfere with the arrest of five rights activists by the Maharashtra Police in connection with the Koregaon-Bhima violence case and declined to appoint a SIT to probe their arrest.

The three-judge bench headed by Chief Justice Dipak Misra, in a 2:1 verdict, refused the plea seeking the immediate release of the activists.

The majority verdict said accused persons cannot choose which investigating agency should probe the case, and this was not a case of arrest merely because of difference in political views.

Justice A M Khanwilkar read out the majority verdict for himself and the CJI, while Justice D Y Chandrachud said he was unable to agree with the view of the two judges.

Justice Chandrachud, in his judgement dissenting with the majority, said arrest of the five accused was an attempt by state to muzzle dissent, and dissent is symbol of a vibrant democracy.

The five activists -- Varavara Rao, Arun Ferreira, Vernon Gonsalves, Sudha Bharadwaj and Gautam Navlakha -- are under arrest at their respective homes since August 29.

The Maharashtra Police had arrested them on August 28 in connection with an FIR lodged following a conclave -- ‘Elgaar Parishad’ -- held on December 31 last year that had later triggered violence at Koregaon-Bhima village in the state.

Prominent Telugu poet Rao was arrested on August 28 from Hyderabad, while activists Gonsalves and Ferreira were nabbed from Mumbai, trade union activist Sudha Bharadwaj from Faridabad in Haryana and civil liberties activist Navlakha from Delhi.

The majority verdict said the protection of house arrest of the activists will remain in force for four more weeks to enable the accused to seek appropriate legal remedy at appropriate legal forum.

It said arrests were not because of dissent of activists but there was prima facie material to show their link with a banned CPI (Maoist) organisation.

The majority verdict disagreed with the PIL by historian Romila Thapar and others seeking the immediate release of five rights activist, with liberty to the accused to seek remedy in appropriate court.

Justice Khanwilkar said the protection of house arrest shall remain in force for four weeks to enable the accused to seek legal remedy.

He refrained from commenting on the case, saying it may prejudice the case of accused and prosecution.

Justice Chandrachud said liberty cherished by the Constitution, would have no meaning if persecution of the five activists is allowed without proper investigation.

He said the petition was genuine and lashes out at the Maharashtra Police for their press meet and distribution of letters to the media.

Justice Chandrachud said the court should proceed as if personal practices are essential but whether they are derogatory to liberty, dignity enshrined in Fundamental Rights.

He said letters alleged to be written by activist Sudha Bharadwaj were flashed on TV channels. Police selectively disclosing the probe details to media amounts to casting a cloud on fair investigation, he said.

The losing counsel’s critique of the judgement

Abhishek Singhvi, Flawed Koregaon Bhima Judgment, October 3, 2018: The Times of India

Justice Chandrachud’s soaring dissent is an appeal to the brooding spirit of law

All fundamental rights are vital but if forced to prioritise, liberty must stand first. Judges must bend over backwards to exercise that bit of extra discretion to uphold liberty, more than any other virtuous goal of our Constitution. Sadly, the Supreme Court (SC) in its majority judgment in Koregaon Bhima (KB) fails this acid test while Justice Chandrachud’s soaring dissent is likely to find a resounding echo in a future majority.

As i was the lead (and losing) counsel for the petitioners you are entitled to discount everything in this article, ascribing it to a poor loser. But my sense of dissatisfaction arises not from the loss but simply because the core and dispositive issues argued were not even addressed, even by way of rejection, by the majority.

Barring the first two, the following powerful and cumulative aggregation of admitted circumstantial facts were regrettably not even discussed nor even prima facie rejected by the majority. The detainees were not named in the FIR; they were admittedly not present at the KB event; the fact-finding report of the Committee admittedly constituted by an IG of police found material evidence to conclude that KB violence was preplanned by right wingers Bhide and Ekbote; this was also the state government’s stand on affidavit in SC in earlier cases; nonetheless, one was never arrested and the other released on bail within one month.

Additionally, two press conferences by the police flashed 13 letters selectively insinuating guilt, but the letters were not placed in SC nor mentioned in the transit remand. No fresh FIR was filed regarding the PM assassination plot and, as the dissent tellingly points out, “no effort has been made by the ASG to submit that any such investigation is being conducted in regard to five individuals (petitioners). On the contrary, he fairly stated that there was no basis to link the five arrested individuals to any such alleged plot against the PM. Nor does the counter affidavit make any averment to that effect”. None of this is mentioned in the majority.

The alleged materials against arrestees were gathered from third persons and the PM plot was based upon letters sent or received by one “Comrade R”. A final trial court judgment after full trial convicted Saibaba and returned a judicial finding that Comrade R was in fact none other than Saibaba, who was admittedly always under police/ judicial custody from months before the allegedly inculpatory letters were written. How a convict under custody could write or receive letters plotting to assassinate the PM remains a grand mystery which the majority does not even note. One letter appeared to be an obvious fabrication since it has over 17 references to words ascribed in Devnagari using Marathi forms of grammar and address, while the alleged author Sudha is non-Marathi.

Law mandates the presence of at least one independent witness who is a respectable member of the locality where the arrest is made, whereas the two Panch witnesses in the KB case are admittedly employees of the Pune Municipal Corporation who admittedly travelled with the police from Pune to Faridabad! Both this and the fact that 99.99% of the over 50 prior criminal cases collectively attributed to the arrestees had led to discharge, acquittal or quashing are ignored. The majority does not even note the total absence of evidence showing membership of CPI (Maoist), much less activity by arrestees on behalf of it and ignores the many judicial precedents appointing SITs and holding direct petitions in SC to be maintainable.

It oversimplifies by addressing only two points, viz whether the investigating agency should be changed at the behest of the five accused and whether a SIT should be appointed. As is obvious, even these two issues are opposite sides of the same coin. The other issues relating to locus had vanished as the arrestees themselves had filed applications directly in the SC.

Ironically, this sole issue on which the entire operative part of the majority (from paras 20 to 37) is based also does not arise for the simple reason that the petitioners had repeated in writing and oral arguments that they wanted neither exemption from investigation nor transfer from or substitution of the investigating agency. An SIT was only asked for supervisory purposes to lend independence and credibility to the investigation, which would continue to be done by the state prosecuting agencies.

By contrast, the dissent is masterful in its language, eloquence, comprehensiveness and soaring spirit. It will, in times to come, indubitably satisfy the prophetic words of a former US SC chief justice: “A dissent in a court of last resort is an appeal to the brooding spirit of law, to the intelligence of a future day when a later decision may possibly correct the error into which the dissenting justice believes the court to have been betrayed.”

Each one of the relevant probative issues listed above (and ignored by the majority) has been painstakingly addressed in the dissent. The judicial precedents cited by the petitioners have been approbated while state citations have been carefully and convincingly distinguished. The dissent sees judicial interference on such core issues of liberty as the “constitutional duty of the court so that justice is not compromised” and “not derailed”. It treats a fair investigative process as “the basic entitlement of every citizen faced with allegations of criminal wrongdoings” and “dissent as a symbol of a vibrant democracy (where) voices in opposition cannot be muzzled by persecuting those who take unpopular causes.”

The writer is National Spokesperson, Congress and former Chairman, Parliamentary Standing Committee on Law. Views are personal

See also

Battle of Bhima- Koregaon: 1818