Census of India

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Modern-day census started in 1881

When were the earliest censuses conducted in India?.

The third century BC treatise of Kautilya, ‘‘Arthashastra’’, which lays down the principles of governance, prescribed the collection of population statistics for taxation purposes. It also has methods of collecting population, agricultural and economic statistics. Extensive records of land, production, population, famines, etc, were also maintained during the Mughal period. Ain-i-Akbari also contains comprehensive data about population, industry, wealth, and so on.

However, with the decline of this great empire and the political chaos in its wake, this tradition of data collection went into disuse. The first modern census was conducted between 1865 and 1872 in different parts of the country in a non-synchronous fashion. The efforts culminated in 1872 and hence the year is dubbed as the year of the first population census in India. Synchronous censuses started from 1881 and since then there has been no interruption in the exercise conducted once every 10 years.

Why is the census such an important exercise?

The census is a statutory exercise conducted under the provisions of the Census Act, 1945. It is the most credible source of information about demography, literacy, standards of living, urbanization, languages spoken, fertility, mortality and various other economic and socio-cultural aspects of the country, which underscores its importance for any government. It is also the only source of primary data at village, town and ward level. The delimitation or reservation of constituencies is also done on the basis of census data.

A census also provides the parameters for reviewing the country’s progress and helps the government in assessing the impact of ongoing schemes. The information it provides is crucial for planning and formulation of polices. Census data is also widely used by nongovernment agencies, scholars, business people and journalists. The census process involves collecting data in census form by visiting every house. The data processing is done by Intelligent Character Recognition (ICR) software, which scans the forms and automatically extracts the data.

What is the debate over the caste census?

In all the censuses conducted from 1941, census enumerators collect caste data only for castes and tribes listed in the schedules to Articles 341 and 342 of the Constitution — hence, the only castes pertaining to which data is compiled are the SCs and STs. As a result, there is no authentic data for other castes, including the OBC category. Estimates for these are made either by extrapolation of the 1931 figures or by sampling surveys, both of which are not reliable for obvious reasons.

There is, thus, a strong demand from many that data should be collected on other castes as well, particularly now when government policy provides for reservations for OBCs. Those against a caste census argue that it will increase casteism and widen the caste divide (ignoring the fact that 80 years of not having caste censuses has not made the institution disappear). They also point out that unlike brahmins, who have an all-India presence, most other castes are localised and hence it would be difficult to aggregate the other castes to get a true picture of the OBC population.

The scope of the census over the decades

Lalmani Verma, May 5, 2025: The Indian Express

To collect details and data on the caste of respondents as part of the upcoming Census, the government will have to expand the questionnaire from the set that was used in the previous edition of the exercise.

Census data are self-reported, and enumerators record the information that is provided to them by respondents.

The first Census of 1872, which was conducted non-synchronously across India, put a set of 17 questions to respondents; the questionnaire of the last Census of 2011 had 29 questions and collected more data points. These 29 questions were almost the same as those asked in the previous (2001) Census as well.

Major changes in the list of questions to collect specific details were made in 1941 and 1951, the Census exercises that immediately preceded and followed Independence.

Here’s how the patterns of questions put to respondents have changed over the years.

1872: One hundred and fifty three years ago, data were collected based on details for House register: number of houses, whether terraced, tiled, or thatched; name of males and females, age, religion, caste or class, “race or nationality or country of birth”; occupation of males; youths up to age 20 years attending schools, college, or under private tuition; the ability to read and write; and the number of males and females who were blind, deaf, dumb, insane or lepers.

1881: More questions were added to this set in 1881 to collect four additional pieces of information — marital status, mother tongue, occupation of females, and sect of religions (other than Hindu).

1891: In 1891, information was collected on 14 questions, including caste and race, and the knowledge of any foreign language.

1901: The next Census was conducted with 16 questions. Apart from Hindus, the caste of Jains, and the tribe or race of others was asked, as well as the subsistence of dependents on actual workers. It was also specifically asked whether the person enumerated knew English.

1911, 1921: The questionnaire for this Census had a column in which Christians were asked their sect. The next Census held in 1921, had a similar set of questions.

1931: Among the new questions asked in 1931 were the industry in which employees in the organised sector worked, and what languages apart from their mother tongue they used.

1941: The last Census before Independence had a 22-question questionnaire, and sought specific information such as the number of children born to a married woman and the number surviving, her age at the birth of first child, etc.

It also asked if the respondent employed paid assistants and members of the household, and whether the enumerated person was employed or in the search of employment, and since when. Details of examinations passed were sought.

1951: The first Census after Partition and Independence asked questions on nationality and displaced persons. Caste, asked in 1931 and 1941 (even though the caste data collected in 1941 was not published), was not in the list of questions in 1951.

Questions on health and family included those on fertility, duration of marriage and size of the family (such as completed years of married life and age of mother at first maternity), number of children born, and number of children who were alive at the time. It also had questions on infirmities and the relationship of the individual with the head of family.

On employment, the questionnaire asked whether the respondent was unemployed since February 9, 1951 and, if so, the reason. There were questions on the area of land owned or cultivated by the household.

The Census asked about indigenous persons in Assam. It was on the basis of this data, which was copied out in registers, that a National Register of Citizens (NRC) was later published in Assam.

In respect of each village showing the houses or holdings in serial order, it was indicated, against each house/ holding the number and names of persons living therein; and in respect of each individual, the father’s name/ mother’s name or husband’s name, nationality, sex, age, marital status, educational qualification, means of livelihood or occupation and visible identification mark.

1961, 1971: The column of Scheduled Caste/ Scheduled Tribe (SC/ST) was incorporated for the first time in the 1961 Census. However, the castes of individual respondents were not specifically asked.

Apart from the nature of work, like working as a cultivator, agriculture labourer, and industry, the trade and name of the establishment were asked. This was sought even if the person was not working.

The 1971 Census compiled similar information.

1981: A major change was the asking of the name of the caste/ tribe among SCs and STs, and the reason for migration. Also, the gender of children was asked for the first time.

1991: Similar information was collected in the 1991 Census with an additional detail about ex-serviceman (pensioner/ non-pensioner).

2001: In the 2001 census, economic activity of main or marginal workers, type of worker (employer/ employee/ single worker/ family worker), and non-economic activities were asked. If the person had to travel to their place of work, the distance from their residence to place of work (in kilometres) and the mode of travel were asked.

Constitutional/ legal requirement

Amitabh Sinha/ The missing Census and its consequences/ The Indian Express / May 24, 2023

A Census is Constitutionally mandated in India. There are repeated references to the Census exercise in the Constitution in the context of reorganisation of constituencies for Parliament and state Assemblies. But the Constitution does not say when the Census has to be carried out, or what the frequency of this exercise should be. The Census of India Act of 1948, which provides the legal framework for carrying out the Census, also does not mention its timing or periodicity.

There is, therefore, no Constitutional or legal requirement that a Census has to be done every 10 years. However, this exercise has been carried out in the first year of every decade, without fail, since 1881. Most other countries also follow the 10-year cycle for their Census. There are countries like Australia that do it every five years.

It is not the legal requirement but the utility of the Census that has made it a permanent regular exercise. The Census produces primary, authentic data that becomes the backbone of every statistical enterprise, informing all planning, administrative and economic decision-making processes. It is the basis on which every social, economic and other indicator is built. Lack of reliable data – 12-year-old data on a constantly changing metric is not reliable – has the potential to upset every indicator on India, and affect the efficacy and efficiency of all kinds of developmental initiatives.

Besides, a break in periodicity results in data that is not comparable in some respects to the earlier sets.

Census schedule

The Census is essentially a two-step process involving a house-listing and numbering exercise followed by the actual population enumeration. The house-listing and numbering takes place in the middle of the year prior to the Census year. The population enumeration, as mentioned earlier, happens in two to three weeks of February.

The numbers revealed by the Census represent the population of India as on the stroke of midnight on March 1 in the Census year. To account for the births and deaths that might have happened during the enumeration period in February, the enumerators go back to the households in the first week of March to carry out revisions.

There are several intermediate steps as well, and preparations for the Census usually begin three to four years in advance. The compilation and publication of the entire data also takes months to a few years.

1871: the first British census

SEPTEMBER 22 | 1871 COUNTING PEOPLE, LAYING TRACKS

Early Firsts | The train and the census were born out of an urgency to map and network this country’s diverse regions & people Locals feared ‘Kumpani’ taxes, arrests

The British carried out their first nation-wide survey of India in 1871, an exercise they began preparing for well in advance in 1869, as the Times of India reported on July 2 that year. [India’s own tradition of census dates back to several centuries before.]

The 1869 report says: “As the want of anything like even an approximate knowledge of the population was much felt, the government of India submitted a recommendation to Her Majesty’s government that arrangements should be made for undertaking a general census of the population of India in 1871.”

The secretary of state, reported TOI, appreciated the urgent need for such an exercise. “The government of India in a letter dated August 20, 1867, requested...that the...proposed census of 1871 might be taken into consideration and that the government of India might be furnished by January 1, 1870, with reports as to the best mode of effecting it.” The 1871 census would take place with the rest of the British Empire.

Another report mentioned how eight local governments had been instructed to “familiarize the minds of people with the idea of a census”. The statistical committee was asked to prepare “uniform tables” for the purpose. Despite the elaborate preparations and professed need to sensitize people to the exercise, enumerators ran into myriad problems, amplified in TOI’s columns. “How do you classify the street-side ear-wax cleaner?” A subsequent census threw up another gem. It ended up classifying “mendicants and ascetics with prostitutes since both were termed non-productive workers.”

TOI’s columns are replete with reports and letters-to-editors detailing how local officials and policemen misused the census and made it an exploitative tool. William Drew, a missionary wrote a letter to the editor of Calcutta Examiner, that was reproduced in TOI on September 22, 1871.

Drew wrote, “As the cost will be met from the exchequer, it is fair that all abuses connected should be published to the world.” He detailed his visit to a village Sulkea (see box) where he came across a policeman making a fast buck by misleading villagers. Telling them census details would be used to levy taxes, he offered to register incorrect details of a family for a price. “This way, partly by intimidation and partly by an unquestioned assumption of authority and superior knowledge, this worthy ... a rich harvest from Her Majesty’s hard-pressed and down-trodden subjects. Of what worth the census will be after passing through such processes, I leave it to the government and the public to judge,” concludes Drew.

An informal process of enumeration was on in India since 1849, when Gov-general Dalhousie asked the local presidencies to record revenue collection details. The first was in 1851-52, the second in 1856-57. The revenue collection details of 1871 were merged into the first official census in 1871 recorded during the tenure of Lord Mayo. TNN L E T T E R TO T H E E D I TO R Ihad occasion to visit the village of Sulkea (24-Parganas). People...began to interrogate me as to the real intention of the census, about which they had heard very diverse accounts. Towards end of the...week there arrived a police official from the local thana...authorizing him to take the census. After making the purport of his visit known, he let them into the secret of the real intentions of the government. He informed that the “Kumpani” had it in mind to levy a tax upon “families”; and that the incidence of it would be heaviest upon the largest (family). He made them to understand that he was not quite in agreement with the sircar, and was prepared for a small consideration (only a few pice) to make it easy by scaling down the number in each family to hide the truth. The Times of India

1981-2011: the population not counted

28m people in Census blind spot

The Times of India Subodh Varma Sep 27 2014

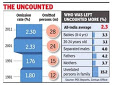

Exercise In 2011 Missed 2.3% Of Population, Finds Post-Enumeration Survey

The Census of India in 2011 left out about 28 million people from its headcount. This is the startling conclusion of a survey carried out by the Census people themselves, a few months after the enumeration work finished in March 2011. Called the Post-Enumeration Survey (PES), it was a near repeat of the Census, except that it was carried out to cover only about 4 lakh people across the country .

The 2011 census counted over 1.2 billion Indi ans, collecting about 30 bits of individual information from them, besides 35 other queries about their households. That's big data.

Compared to this, the 28million uncounted make up just 2.3% of the population.This small share means there is no cause for alarm, the Census office says. Nothing will have to be changed. In 2001, the net omission rate was roughly the same, although it was lower in 1991 and 1981.

How did so many people go uncounted in a rigorously designed survey like the Census? “Most of this occurs because of hard-to-reach people, particularly people with no fixed residence such as street people, and because of people who are travelling,“ explains Pronob Sen, chair person of the National Statistical Commission.

“An estimated coverage omission rate of 2.3% is by no means unusual or excessive even if it adds up to 2.8 crore people. It does not really lead to any serious bias. If the omission rate was higher than 5%, then a more substantive survey would have had to be done to correct the Census estimates. To put it in perspective, the NSSO surveys underestimate population by a much higher proportion (6 to 12%),“ he told TOI.

Among the uncounted, some strange facts emerged.The share of people left out was higher in some states. In the central zone made up of UP , Uttarakhand, MP , Chhattisgarh, about 4.2% of the people were omitted. That's close to the statistically permissible limit of 5%. But the most bizarre finding is this: fathers and mothers of the head of the household were more likely to be omitted. But the worst were unrelated persons staying with the family , like servants. Over 15% of these were not counted.

Census 2011: What is new?

In the 15th census, officials will also record access to new age technologies like mobile phones, computers and internet connections. Also, for the first time, a comprehensive database of all the usual residents of the country will be made. The database will be known as the National Population Register (NPR) and is estimated to cost over Rs 3,500 crore. The NPR will include information like name, sex, education and occupation of every usual resident of the country.

The database will also contain photographs and finger biometry of persons above the age of 15 years. After the finalization of the database, every individual will be assigned a Unique Identification Number (UID) and an identity card containing basic details will be issued. Although both processes are carried out together, the NPR is different from the census because unlike the census, which requires a particular manpower for a limited period of time the NPR is a continuous process and the database will be regularly upgraded.

2021

The logistics

From: Sep 25, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic, ‘ What it will take to conduct the Census of India in 2021. ’

The missed/ delayed 2021 census

Amitabh Sinha/ The missing Census and its consequences/ The Indian Express / May 24, 2023

A bulk of the work for the 2021 Census was completed before Covid-19 hit the country. It was initially proposed to be an entirely digital exercise, with all the information being fed into a mobile app by the enumerators. However, owing to ‘practical difficulties’, it was later decided to conduct it in ‘mix mode’, using either the mobile app or the traditional paper forms.

Covid struck in India in March 2020 while the housing census was to begin on April 1. Lockdown was imposed just a week before the housing census was to start. What has been inexplicable, however, is the failure to resume the Census exercise in 2023, if not in 2022 itself. Most normal activities had been restored by the middle of 2022 after the dwindling of the third wave of the pandemic.

Interestingly, many other countries have carried out their Census either during, or after, the pandemic. These include the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.