Craftsmen castes: Sholapur

Craftsmen castes: Sholapur

This is an extract from a British Raj gazetteer pertaining to Sholapur that seems |

Craftsmen

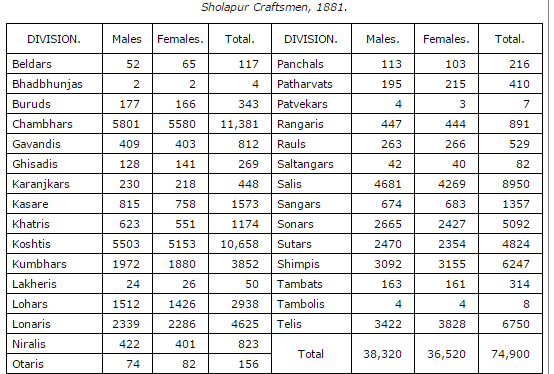

Craftsmen, include thirty classes with a strength of 74,900 13.9 per cent of the Hindu population. The details are:

Belda'rs, or Quarryrnen, are returned as numbering 117 and as found in Barsi, Karmala, Sangola, and Sholapur. They are strong and dark and the men wear the moustache and top-knot. They speak Marathi. They are stone-cutters and bricklayers, digging wells, blasting rocks, and breaking stones. Their houses are like those of cultivating Marathas. The men wear the loincloth, waistcloth, and short tight trousers or cholnas, the jacket, and the Maratha turban; and the women dress in the ordinary Maratha robe and bodice and do not tuck the end of the robe back between the feet. They eat fish and flesh and drink liquor. They are hardworking, orderly, and hospitable but fond of drink. They have caste councils, do not send their boys to school, and are a steady people earning enough to maintain themselves.

Bhadbhunjas

Bhadbhunja's or Grain-Parehers, are returned as numbering four and as found in the Sholapur town. They are divided into Marathas and Pardeshis. The following particulars apply to the Maratha Bhadbhunjas. Their surnames are Gaikavad, Jadhav, Povar, and Sinde, who eat together and families with the same surname do not intermarry. They look like Marathas, speak Marathi, and live in houses the same as Maratha houses except for the furnace orbhatti and a shop in the veranda. In dress and food they resemble Marathas, eating fish, fowls, and the flesh of the hare, deer, and wild hog. They are an orderly, sober, hardworking and even-tempered people. In addition to parching and selling grain and pulse, they sometimes serve as day labourers, entrusting their shops to their wives and children. They sometimes borrow money and have to pay interest at two, three, or even four per cent a month. They always borrow small sums never as much as one hundred rupees as no one will advance them that sum on the security of their goods. In religion, customs, and community they are the same as Marathas. They send their boys to school and are a poor people. ==Buruds==. Buruds, or Bamboo-workers, are returned as numbering 343 and as found in towns and large villages. According to their own account they are descended from Kenshuka, whose father's name was Bhivar and his mother's Kuvinta, and they are said to have come into the district five or six generations back. They are dark and strong and the men wear the top-knot and moustache. They speak Marathi both at home and abroad, and live in untidy and ill-cared for grass huts or houses of stone and mud with flat or tiled roofs. Their house goods include earthen and a few metal vessels. They keep no servants and a few own cows, buffaloes, and sheep. They do not eat beef or the flesh of dead cattle. Their staple food isjvari, vegetables, and chillies. They drink liquor sometimes to excess. The dress of the men and women is the same as the Mhar's dress. They are hardworking, patient, and forbearing, but intemperate and dirty. They make bamboo baskets, mats, winnowing fans, and sieves, and a few make cane chairs and cots. In Pandharpur they find good employment in making fine bamboo sticks for the use of the frankincense stick preparers. Their women, besides minding the house, help them in their work of making and hawking fans and baskets. They belong to no particular sect, and worship all Hindu gods and goddesses, chiefly Ambabai, Jotiba, Khandoba, and Satvai. Their priests are village Brahmans and they have no priests belonging to their own caste. They keep all Hindu fasts and feasts and believe in sorcery and witchcraft. They marry their children early; the girls between seven and twelve, and the boys between twelve and twenty. The cost varies from £2 10s. to £6 (Rs. 25 - 60). Except that their guardian or devak is the mango tree, branches of which are brought home and tied to the marriage hall, and that the boy and girl are married on the earthen altar or ota, their marriage and funeral ceremonies are the same as those of Mhars and Mangs. They generally bury their dead. They allow widow marriage making over the first husband's children to his relations. They have a caste council, and their headman, who is called mhetrya decides social disputes in consultation with a few leading members of the caste. The fine generally takes the form of a caste feast. They do not send their boys to school, and, as their calling is not well paid, many have turned Varkaris or Pandharpur holy ==time keepers and go about begging.

Chambhars

Cha'mbha'rs, or Leather-workers, are returned as numbering 1131 and as found all over the district. Their surnames are Dhodke, Kamble, and Vaghmare. Families with the same surname eat together but do not intermarry. They are generally rather fair with regular features, and the men wear the top-knot and moustache, and a few the whiskers. They speak Marathi and live either in grass huts with thatched roofs or in mud and stone houses with flat roofs, setting apart the veranda for a workshop. They keep cattle, goats, and sheep, and their houses are dirty and ill-cared for. They eat fish and flesh and drink liquor. The men wear a loincloth and blanket, and occasionally a waistcloth, jacket, and turban. The women dress in the usual Maratha robe and bodice. Their ceremonial dress is the same as their everyday dress except that it is clean. They are hospitable and forbearing, but fond of drink, and proverbially lazy, as the saying goes, Under his haunches the awl, and in his house starving children. [The Marathi runs: Gandikhali ari ani gharant pore mari.] They work in leather, cut and dye skins, make sandals shoes and water bags, and till the ground. The women help the men in drawing silk flowers and making silk borders to the shoes. Some serve as labourers and hold torches in marriage processions. They worship the ordinary Hindu gods and goddesses, and have house images of Bahiri, Jotiba, Khandoba, and Mhasoba. They keep the usual Hindu fasts and feasts, and their priests are village Brahmans to whom they pay the greatest respect. They worship Satvai on the fifth day after childbirth, name the child either on the twelfth or the thirteenth, and clip the child's hair within four to six months. With them marriage is preceded by betrothal. Before marriage they rub the boy and girl at their houses with turmeric, and as a guardian or devak tie panchpalvis or five tree leaves that is of the mango, the umbar Ficus glomerata, the jambhul Syzigium jambolanum, the saundad Prosopis spicegera, and rui Calotropis gigantea to a post of the booth and worship them, offering a fish and feasting on its flesh. The poor bury the dead and those who can afford it burn them. They allow widow marriage, the widower during the ceremony being seated on bullock harness and the widow on a low wooden stool. They have a caste council and settle social disputes in presence of the headman. They do not send their boys to school. Their income is fair and enough to keep them.

Gavandis

Gavandis, or Masons, are returned as numbering 812 and as found all over the district. They are divided into Jingars, Jires, Kamathis, Marathas, Panchals, and Sagars. A few Brahmans also work as masons. Of these Jingars, Kamathis, and Brahmans are found in very small numbers in the district, and Panchals are rare.

Jire Gavandis

JIRE GAVANDIS are found only in Pandharpur and Sholapur. They are called Jires after their headman's surname who was the Badshas' or Bijapur kings' builder. They are said to have been Maratha husbandmen who were put out of caste because they refused to pay a fine of £15 (Rs. 150) which their castefellows levied on them for building mosques for the Adil-Shahi kings (1490-1686) at Bijapur. They say Marathas are willing to let them back, but that they do not wish to go back, because the Marathas have lately taken to eating, and, in out-of-the-way places, marrying with Telis and Sangars. The Jires and Marathas eat together, and their married women or savashins attend feasts at one another's houses. Bodhlebava, a great Maratha saint, whose headquarters are at Dhamangaon in Barsi, is anxious that the Jires should go back and join the Marathas. The Jires are said to have come into the district seventy or eighty years ago to build Sindia's mansion in Pandharpur. They have Kadus or bastards among them, with whom they eat but do not intermarry. The Jire surnames are Kamle, Pavar, Salunke, and Surve, and families having the same surname do not intermarry. The names in common use among men are Apa, Balvanta, Ganpati, and Rama; and among women Elubai, Ittai, Bakkumai and Subai. All belong to the sun family called Surygotra or Surugotra. Neither men nor women differ from cultivating Marathas in look, speech, house, dress, or food They eat fish and the flesh of goats, sheep, rabbits, hares, and fowls, and their staple food is bajri, tur, jvari, milk, and every two or three days rice. They drink liquor once or twice a year especially on the last day of the Shimga or Holiholidays in March-April. They are not great eaters or drinkers, neither are they good cooks. There is nothing special or proverbial about their cooking Before beginning to dine, they sprinkle a little cold water round the dining plate and sip some water repeating the wordsKrishnarpan that is for the acceptance of Krishna. The Jires are hardworking, eventempered, sober, thrifty, hospitable, contented, and orderly They are masons and husbandmen and their women mind the house Their boys begin to help from fifteen or eighteen, A trained mason earns £1 10s. to £3 (Rs. 15-30) a month. All find constant employment. They build houses, ponds, wells, bridges and temples, and cave stone or mould clay images of gods and animals, which they sell at 3d. to £20 (Rs. £ - 200). Their craft prospers and they have credit being able to borrow at twelve to eighteen per cent a year and almost never fail to pay their debts. Their family deities are Bhavani of Tuljapur, Jakhai and Jokhai, and Khandoba of Jejuri. They also worship all Brahmanical gods and goddesse and keep the regular fasts and feasts, Their priests are the ordinary Maratha Brahmans, before whom they bow and whom they worship as gods. Their gurus or religious teachers are either Gosavis or Brahmans. When a child or a grown person is initiated the teacher whispers into his right ear a sacred verse. A year or two after marriage they generally go and seek the advice of the teacher. They believe in sorcery witchcraft and soothsaying, and, when sickness comes to a family, they consult a seer or devrushi as to the best means for driving out the evil spirit. When a boy is twelve, sixteen, or eighteen years old his parents think of marrying him The girl chosen to be his wife is generally eight to twelve years old, but they have no rule that girls should be married before they come of age. Before a marriage can be fixed, the parties must ascertain that the boy and girl have different surnames and have not the same guardian ordevak. After talking the matter over with his wife and the elderly women of his house and fixing on some girl the boy's father goes to a Brahman and asks him when he should set out to make an offer of marriage for his boy. The Brahman, who is generally a village astrologer names the day, and the boy's father, tying in a cloth a few cakes and some vegetables, fried fish, and pounded chillies, starts for the girl's with a kinsman or two. When they reach the girl's, the boy's father makes over the bundle of cakes to the women of the house, and the fathers sit on the veranda, on a blanket spread for them, talking the matter over, asking one another the boy's and girl's ages, their surnames, and their guardians or devaks. After some pressure the girl's father agrees to give his daughter, and they sup together often from the same plate. Next morning the fathers go to the village Brahman, and tell him the boy's and the girl's names, eat a dish of rice and sugar, and settle what presents each is to make to the other's child. Next day some of the boy's kinspeople bring a robe and bodice, go to the girl's house and present it to her. From this time marriage preparations are pressed on. When the Brahman has fixed a lucky evening for the wedding, word is sent to the girl's parents, and the boy's father sends invitations to relations and friends. Marriage booths are built at both houses. Except that an altar is built at the girl's, the preparations at both houses are the same. Musicians are called and early in the wedding morning at the girl's house, the house handmill is washed, and turmeric roots are ground to powder. The girl's head is rubbed with oil and her body with turmeric and she is bathed with a band of little children. When all the children have bathed, the girl's mother sits by her and bathes, and her kinspeople present her with a new robe and bodice. The girl is dressed in a robe and green bodice, her clothes are stained with turmeric, and her brow marked with redpowder. A flower or a tinsel chaplet is tied round her brow and her head is covered with a blanket. By this time the boy has been rubbed with turmeric and bathed. He is then dressed and a tinsel chaplet is tied to his brow. The guests feast, and, seating the boy on a horse or bullock, with music and friends go to the girl's village Maruti, and from it to the boundary of the girl's Village. The girl's friends come and bring them to the village temple, they bow before the god, and the boy is led to the door of the girl's marriage hall, bathed, dressed in new clothes, and seated near the outer wall of the house. The girl is seated on the boy's left. They are then made to stand facing each other, and a cloth is held between them. Behind the girl and the boy stand their maternal uncles and their sisters or karavlis with lighted lamps in their hands. The boy's brother also stands behind him with a lemon stuck on the point of a dagger. The Brahman repeats verses, and the guests throw rice over the pair. At the end of the verses the Brahman claps his hands, the musicians play, and the boy and girl are husband and wife. Then the boy and girl are seated on the altar, the girl on the boy's left. They dine and the guests either stay for the night or go home. On the fourth day the boy takes the girl' to his own house. Jires allow widow marriage and polygamy. When a girl comes of age she is seated in a room by herself for four days. On the fifth she is bathed and word is sent to her parents. She is given a cot, bedding, waterpots, and a robe and bodice, and the boy is given a turban. A feast is held and the girl is told to make the bed ready, and the boy and girl are shut in the room. A young wife generally goes to her parents for her first child. When a child is born a Brahman is asked to name it. The midwife cuts, the navel cord, bathes the mother and child in warm water, and swathes the child in cloth bandages. A piece of cloth soaked in cow's milk is put in the child's mouth, and the mother is fed on rice, butter, and warm water. A lamp is kept burning in the room, and, on the fifth day, the goddess Satvai is worshipped, and on the twelfth day the child is named. When a Jire is on the point of death, his son lays his father's head on his right knee and drops water into his mouth. When he breathes his last some Ganges or Godavari water and tulsi leaves and a piece of gold are put in his mouth. The body is brought out of the house and laid on the door-step with its feet to the road. Warm water is poured over it, it is laid on the bier, and covered from head to foot with a sheet. On the sheet is sprinkled redpowder or gulal and basil leaves, and two copper coins and a handful of grain are tied in the hem of the sheet. The chief mourner ties a piece of white cloth across his shoulder and chest. Then holding in his right hand an earthen jar with live coal in it, the chief mourner starts, and four near kinsmen lift the bier and follow. At the burning ground a stone called jivkhada or the stone of life is picked up, and kept in some safe place in the burning ground. The bier is set on the ground and the pile is made ready.

The chief mourner bathes, brings a potful of water, pours a few drops into the dead mouth, and lights the pile. He takes the jar, bores holes in it, walks three times round the pyre, dashes the pot on the ground, and beats his mouth with the open palm of his right hand. Then they bathe and go back to their homes. While the funeral party are away, at the chief mourner's house the spot where the deceased breathed his last is cow dunged, a cup of milk and a lighted lamp are set on it, and the ground is strewn with wheat or rice flour. The neighbours come with cooked food, serve it to the mourners, and dine with them. In the evening they look for the marks of an ant or other insect's feet, and from the footsteps judge that the deceased has died happy and his spirit has passed into an ant or a fly. If no footsteps are traced, the dead is believed to have had some unfulfilled wish or care that keeps him from leaving the earth. They beg him to come and drink and leave his footsteps' that they may not be anxious what has come to him. This is repeated night and day, the people if no traces are shown puzzling what can be the deceased's unfulfilled wish. On the third day, the chief mourner with some near kinspeople goes to the burning ground and throws the ashes into water. The crows are offered rice balls, and they are asked to come and eat them. If the crows come and touch the balls, it is believed that the soul of the deceased is happy; if the crow refuses to eat the mourners pray the dead to say what ails him, and promise to fulfil his wishes. For ten days the house is in mourning. On the eleventh the whole house is cowdunged, and on the twelfth and thirteenth cooked food and rice balls are again offered to the crows. The chief mourner does not become pure till the morning of the thirteenth, when the whole house is cowdunged, uncooked food and money presents are made to Brahmans, and the caste is feasted. The Jires are bound together by a strong caste feeling. They have no headman and settle their social disputes at meetings of their own and other castemen. The power of caste has of late grown weak. The Jires can read and write Marathi both Balbodh and Modi, and keep their boys for long at schools. They are a steady and contented if not a rising class.

Sagar Gavandis

Sagar Gavandis claim to have come from Benares in search of work to the Nizam's Haidarabad. Their castefellows are still found near Haidarabad some of them wearing sacred threads and dining in silk waistcloths. They occasionally come on pilgrimage from Haidarabad to Pandharpur when they dine with the Sholapur Sagars, but not unless the local Sagars dress in a silk or in a fresh washed waistcloth. They are said to have come into the district about three hundred years ago, and are divided into Sagars proper and Lekavlas or Kadus that is bastard Sagars who eat together but do not intermarry. The names in common use among them are Govind, Nagu, Narayan, and Narsu; and among women Bhagirthi, Kashi, Yamuna, and Yashvada. Their surnames are Gadpate, Kalburge, Kasle, and Narne; and families bearing the same surnames do not intermarry. All belong to the Kashyap family stock. Both men and women look like Maratha husbandmen, the men wear the top-knot and moustache, but not the beard, and mark their brows with sandal. Their home tongue is Marathi, but those who are settled in the Karnatak and Moghlai or Nizam's country speak Telugu. Their houses are the same as Maratha houses with mud and stone walls and flat earth roofs and their house goods include cots, boxes, metal and earthen vessels, clothes, cattle, and ponies. They eat fish and the flesh of sheep,goats,hares,rabbits,and fowls, and their staple food is jvari, tur, bajri, and occasionally rice and wheat bread. Formerly all ate flesh whenever they could afford it without offering it to the gods. Many of them keep to the old practice, but some who have become varkaris or Pandharpur devotees, offer no sheep, goats, or fowls, have given up eating flesh and drinking liquor, and have taken to wear a necklace of tulsi beads. For their holiday dinners they prepare grain and wheat cakes. They drink liquor but only twice or three times a year on great occasions like Sankrant in January and Shimga in March. They are not great eaters or drinkers, neither are they good cooks. There is nothing special or proverbial about their cooking or their pet dishes. Their only peculiar practice at meals is before beginning to eat to lay some cooked rice for the god Agni or fire in front of their plates. Both men and women dress like Marathas, the men in a waistcloth, turban, jacket, coat, shoulder-cloth, and shoes, and the women in a robe and bodice. The women do not deck their heads with flowers or false hair. Both men and women are fairly neat and clean but they do not show any taste in dress and have no special liking for gay colours. Their holiday dress is made of rich stuff with gold borders. There have been no recent changes in the shape or material. The women wear the nosering, earrings, neck ornaments, bangles, and toe-rings. Men wear a gold neckchain and finger rings, and boys up to fifteen wear wristlets. They are hardworking, even-tempered, sober, thrifty, hospitable, and orderly. Besides by stone-cutting some earn their living as husbandmen and some as labourers. Boys begin to help their fathers at the age of twelve and become skilled workers at the age of twenty-five. A boy gets 8s. to 10s. (Rs. 4-5) a month, and when he becomes a skilled worker his wages rise to 16s. to £1 12s. (Rs. 8-16). Their work is not constant. They sometimes take fields on lease and work in them. They build houses, wells, and bridges, make earth and lime images of Hindu gods and saints, and sell Ganpatis at 1½d. to 6d. (1 - 4 as.). They are not in debt, and are generally able to borrow at about two per cent a month. Sagars claim Kshatriya descent though they admit they have fallen to be Shudras. They eat with Marathas, Dhangars, and Lingayat Vanis, but not with Lingayat Telis, Panchals, Jingars, Sonars, Kasars, or low caste Hindus like Buruds, Mhars, and Mangs. They are a religious people and worship Hindu gods and goddesses as well as Musalman saints and the tabuts or Muharram biers. Their family deities are Balaji of Giri or Tirupati, Bhavani of Tuljapur, Jotiba of Ratnagiri, Khandoba of Jejuri, and Yallama of the Karnatak to whom they sometimes go to pay vows. Their priests are the ordinary Maratha Brahmans to whom they show the greatest respect. The gurus or teachers of some are Ramanujs and of others Shankaracharya. They are either Smarts or Vaishnavs and keep the usual Brahmanic fasts and feasts. They believe in sorcery witchcraft and soothsaying. They marry their girls between seven and twelve, and their boys between twelve and twenty-five. After talking the matter over and fixing on some girl, the boy's father consults a Brahman and starts with a couple of relations for the girl's house. They talk the matter over, and, after some pressure, the girl's father agrees to give his daughter. An astrologer is sent for, the boy's and girl's horoscopes are compared, and, if the horoscopes agree, the parents settle what presents are to be given. The astrologer is asked to fix a lucky day for formally asking for the girl, and, when this is settled, the boy's father returns to his house with his companions. On a lucky day named by the astrologer the boy's kinspeople taking a robe and bodice, a packet of sugar, fruit, dry dates, and betelnut and leaves, go to the girl's house, present her with the robe and the bodice, fill her lap with fruit, dry dates, rice, and betel, and an astrologer is sent for who draws up the marriage papers or patrikas, receives a money present, and retires. The boy's brother or if he has no brother, the boy's father is presented with a turban, a feast is held, and sugar is handed among the guests. Instead of the boy, the girl, with kinsfolk and music, starts on horseback for the boy's. They stop at the village Maruti temple and send word to the boy, and the boy's party come with pots full of cold water, cakes, and millet gruel. After the gruel has been served to such as wish to share it, they are brought into the village and taken to their lodgings. The boy is bathed and rubbed with turmeric, and what is over is sent to the girl's with a robe and bodice. The boy's kinswomen bathe the girl, dress her in the new clothes, and fill her lap with fruit dry dates and betel. Two branches of each of the five guardian trees or panchpalvis that is the leaves of mango, the umbar Ficus glomerata,the jambhulSyzigium jambolanum, saundad Prosopis spicegera, and rui Calotropis gigantea, are laid in an earthen jar and placed in Maruti's temple. Then from both houses a band of kinspeople with music go to fetch the jar or guardian shrine to their houses, place it near the house gods, and worship it with flowers and rice grains. An altar is raised at the boy's with a plantain stem and a pile of six earthen jars at each corner.

A procession is formed and the girl's kinsfolk with the girl carried in the arms of a near relation go to the village temple, and from the temple to the boy's. When the girl reaches the boy's she takes her stand near the door of the booth, the boy's mother waves round her head a cocoanut and cooked rice, and throws it to one side, and the girl walks in with her relations and takes her seat in the house. Two low wooden stools are set in front of the altar, the boy and girl take their stand on the stools face to face, grains of rice are handed to the guests, and, when the Brahmans have finished chanting the marriage verses, the guests throw the rice over the couple and they are husband and wife. Four or five turns of cotton thread are passed round the boy and girl; the threads are offered vermilion and rice, cut, tied round a turmeric root, and bound to the wrist of the boy and of the girl. The priest throws a sacred thread round the boy's shoulders, the boy and girl are seated on the altar, the sacrificial fire is lit, betel is handed, and the guests withdraw. The boy and girl are taken before the house gods, bow to them, and are lifted on the shoulders of two men who dance to music. The day ends with the biting of betel leaf rolls by the boy and girl and the playing of odds and evens with betelnuts, and a feast. Either on the second or the third day after marriage, in the marriage hall, a cot is laid in front of the house door, on which the boy and girl sit near each other. Between them is placed a stone rolling-pin muffled in a piece of white cloth and daubed with turmeric. The pin is by turns placed in the arms of the boy and of the girl, and cold water is dropped on the ground near their feet, and the women call out that the boy's or the girl's child has passed over water. The family priest unties the wedding wristlets, the boy takes off his sacred thread, and after worshipping them they are kept in some corner of the house and in the end thrown away. The girl's father asks the boy's father how many betelnuts he wishes. If the girl's father says twenty, ten are added, and thirty betelnuts are handed to each of the guests whether man woman or child. In this way large quantities of betelnuts are handed round whether or not the guests belong to their own caste. Then except those who have been asked to stay for dinner, all leave. Feasts on both sides end the marriage ceremonies. Their age coming and pregnancy rites are the same as those of the Kamathis. On the fifth day after the birth of a girl's first child the midwife lays healing herbs and roots on a grindstone, and lays vermilion, turmeric paste, flowers, burnt frankincense, and cooked food before them. A feast is held and either five or seven widows are feasted in honour of the goddess Satvai who is believed to be a widow. The women of the house keep awake the whole night. Next morning the midwife carries to her own house and eats the food which the evening before was offered to the healing plants. The plants are taken away and given to the young mother. On the tenth the house is cowdunged, the mother and child are bathed and laid on the fresh washed cot spread with fresh clothes. On the eleventh, as on the tenth, the mother and child are bathed, the cot is washed, and the whole house cowdunged. On the twelfth, five seven or nine pebbles are arranged in a line outside of the house in the name of Satvai, and water is poured over them, red and scented powder sprinkled, flowers rice and sandal strewn, frankincense burnt, and cooked food and two pieces of thread or nadas laid before them. The mother makes a low bow, and retires. In the afternoon the child is laid in the cradle and named, and the thread or nada offered to the goddess Satvai is cut in two, and one-half tied round each of the child's wrists. After three months the father's people fetch the child and its mother to the father's house, and its hair is clipped on some lucky day. When a Gavandi is on the point of death he is laid on a blanket, and water mixed with sweet basil or tulsi leaves, and a piece of gold are put in his mouth. After death the body is bathed in warm water on the house steps, a silk cloth is wound round the waist, and the body is laid on the bier, red and scented powders are sprinkled over it, and it is covered with a white sheet, to whose hem are tied a few grains of rice and a copper coin. Both men and women follow the body to the burning ground. About half-way the bier is lowered, the rice and the copper are laid on one side, the bier is again raised and they go to the burning ground. While the pile is building, the chief mourner bathes and has his head and moustache shaved, and the body is laid on the pile. The chief mourner again bathes, dips the hem of his robe in water, squeezes some drops into the dead mouth, and sets fire to the pile. When the pile is half burnt the chief mourner takes the jar in which he brings fire, fills it with water, bores three holes in it, goes thrice round the pyre and dashes the pot on the ground, and beats his mouth with the back of his hand. Then the mourners bathe, pluck a little grass, return to the house of mourning, and sprinkle the grass on the spot where the dead breathed his last. Ashes are spread on the grass to show footprints, cooked rice is laid close by, and the whole is covered with a basket. Neighbours and kins-people bring cooked food and ask the mourners to eat. They mourn the dead ten days, and on the twelfth hold a feast, when the four bier-bearers are the chief guests. The funeral priest is presented with a cot, bedding, waterpot, umbrella, walking stick, and shoes, to help the dead along the weary way to heaven. The mourners are taken to Maruti's temple, bow to the god, and are brought back, and the neighbours return to their homes. Sagar Gavandis are bound together by a strong caste feeling. They have no headman, and settle social disputes at meetings of men of their own and of other castes. The spread of English law and of lawyers has weakened the power of caste, and the people are afraid to enforce their rules by the old penalties. They send their boys to school till they are about twelve, when their fathers take them to work as masons. Narayan Bapuji a member of this caste was postmaster of Pandharpur for over twelve years and is now a Government pensioner. Another was a telegraph master of the Peninsula railway. The Sagars are beginning to keep their boys longer at school. They are a steady class.

Ghisadis

Ghisa'dis, or Tinkers, are returned as numbering 269 and as found wandering over the whole district. They are said to have originally passed from Gujarat to Haidarabad and from Haidarabad, about five hundred years ago, to Sholapur in search of work. Their commonest surnames are Chavhan, Kate, Khetri, Padval, Pavar, Shelar, Solanke, and Suryavanshi, who eat together and intermarry. They are said to have sprung from Vishvakarma the framer of the universe, who brought out of fire the airan or anvil, the bhata or bellows, the sandas or tongs, the ghan or hammer, and the hatodi or small hammer. He taught the Ghisadis how to make the sudarshan chakra or Vishnu's discus, ban or arrow, trishul or trident, nal or horseshoe, khadg or sword, and rath or war chariot. When these were prepared and approved by their master the caste came to be called Ghisadis and were told to make various tools and weapons of war. They are strong, dark, dirty, drunken, hot-tempered, and hardworking. The men wear a tuft of hair on the crown of the head, and the moustache and beard. They speak a mixture of Gujarati and Marathi. They are wandering blacksmiths and tinkers. They have no regular dwelling but live in the open air, sometimes stretching a blanket over their heads as a shelter. They have cattle, and during the rainy season live in mud or thatched huts. They have a few brass and copper vessels, and are helped in their calling by their wives and children. They eat fish and flesh, and drink to excess. Their daily food is jvari, split pulse, and vegetables. The men wear a turban folded in Maratha fashion, a jacket, a shouldercloth, and a waistcloth; and their women the Maratha robe and bodice, silver ornaments, and the lucky neckthread or mangalsutra. They make horse shoes, field tools including sickles, and cart axles and wheels. They hold their women impure for a month and a quarter after childbirth, and during that time the men do not worship the house gods, rub sandal on their brows, or get their heads shaved. The mother bathes after her impurity is over, and puts new bangles round her wrists, the old ones being removed and carried away by the bangle-seller. A ceremony called panchvi is performed on the fifth day after a birth, and another on the seventh when the child is cradled and named. The child's hair is not clipped until another child is born. If the mother shows no sign of being pregnant, the child's hair is clipped after a couple or three years. On the hair-cutting day the child's maternal uncle first cuts a lock of hair and puts it in a safe place, and the barber shaves off the rest. On some lucky day the lock which was put aside is offered to the village Satvai and a feast is held. The goddess is offered cooked food and is asked to preserve the child. After the hair-clipping the child is bathed and dressed in new clothes presented by its maternal uncle. They have a betrothal ceremony which is performed one to five years before marriage. On the betrothal day, with kins people and music, the girl is taken to the boy's house, is presented with new clothes and full set of ornaments, is feasted, and is sent back. In honour of the ceremony the girl's father presents the caste with £1 10s. (Rs.15) in cash, of which a little is spent in buying gram and molasses, and distributed among relations, friends, and castefellows. The rest is spent on drink and sweetmeats. The boy's father has to give £10 (Rs. 100) in cash to the girl's father. If the boy's father fails to pay this amount, the girl is offered to another boy on payment of £25 (Rs. 250) to the former boy's father. Of this sum of £25 (Rs. 250) £5 (Rs. 50) are given to the caste and £20 (Rs. 200) to the former boy's father, on account of the betrothal ceremony already performed by him and of the ornaments presented to the girl. All the ornaments along with the girl become the second boy's property. No second betrothal ceremony is performed. At the time of the marriage the boy stands with a dagger in his hand in front of the girl on an earthen altar, and a cloth is held between the boy and the girl. The Brahmans repeat verses and they are husband and wife. Four near relations stand on the four sides of the boy and girl and pass cotton thread round them on their thumbs, cut the threads into two parts and tie them with two turmeric roots to the wrists of the boy and the girl. Feasts are exchanged, and the boy takes his wife to her new home, their sisters walking behind them with lighted dough-lamps in their hands. When the boy reaches his house the girl's father presents the boy with 6s. to 10s. (Rs. 3-5) as safety money for bringing home his daughter without accident. This sum is spent either on sweetmeats or on liquor. A girl is held impure for five days when she comes of age. On the sixth day her lap is filled and her parents present her and the boy with clothes. That day is spent in feasting, but no flesh is eaten and no liquor is drunk. They burn their dead and mourn for eleven days. On the eleventh the chief mourner gets his head and moustache shaved, prepares eleven dough balls, and, taking one of the balls in his hands, jumps into the river or stream, leaves the ball at the bottom, and comes out. He does this eleven times, and when all the balls have been left under water he bathes, kindles a sacred fire, goes round it five times, and makes a long bow before it, A feast is held on the spot, and one of the party presents the mourner with a new turban. The Brahman is given uncooked food, and a gondhal or a drum or daur dance is held during the night. On the twelfth his relations friends and castefellows feast the mourner and a sheep is slaughtered for the occasion. On the thirteenth cooked rice, split pulse, and butter are mixed together, served on castor orerand leaves, and laid on the spot where the body was burned, where the bier was rested, and where the deceased breathed his last. The ashes are removed and river water is poured over the spot. After a bath the mourner and his friends return to the mourner's house, sprinkle cold water on the bodies of the house people to make them entirely clean, and to rid him of his mourning, his friends offer the chief mourner a cup of sugared milk, and return to their homes. They allow widow marriage. They settle social disputes at caste meetings, and the fine is spent in drink. They do not send their boys to school and take to no new pursuits. They are a poor class.

Karanjkars and Jingars

Ka'ranjkars, that is Fountain Makers, including Jingars, that is Saddlers, who call themselves Somvanshi Arya Kshatris, are returned as numbering 448 and as found over the whole district. They say that the Brahmand and Bhavishyottar purans contain a full account of their origin. The founder of their caste was Mauktik, Mukdev, or Mukteshvar, whose temple is in Shiv Kanchi or the modern Conjeveram in Madras. The spot where Mukteshvar bathed and prayed is called Muktamala Harini. Even two demons Chandi and Mundi were made holy by bathing there, and bathing at this spot still cleanses from sin. This place the Karanjkars hold to be sacred and make pilgrimages to it. They have no divisions and have eight family stocks or gotras, the names of which are Angiras, Bharadvaj, Garg, Gautam, Kanv, Kaundanya, Valmik, and Vasishth. Their surnames are Chavhan, Gadhe, Gavli, Honkalas, Kale, Kamble, Lohare, Vaghmare, and Vasunde. Of these Chavhans belong to the Vasishth gotra, Mukteshvar pravar, Rudragayatri, Rigved, and the colour of the horse and chariot is white or shvet. Families belonging to the same family stock eat together but cannot intermarry. They have regular features and are neither dark nor fair. The men wear the top-knot and moustache and rub sandal on their brow. Their women, who are fair and pretty, tie the hair in a knot behind the head and rub redpowder on their brows. They use false hair but do not deck the head with flowers. The home tongue of most is Marathi, but some speak Kanarese both at home and abroad. Their houses are generally built of mud and stone with flat roofs, having a veranda or room in the front of the house to serve as a shop. Their houses are neat and clean and well-cared-for, and they keep servants to help in their shops, and cows, she-buffaloes, and parrots. They have generally a good store of brass copper and earthen vessels. They are not great eaters or drinkers, and their every-day food consists of rice bread, pulse, and vegetables. They eat fish and flesh and drink liquor. The men dress like Deccan Brahmans in a waistcloth, coat, waistcoat, shouldercloth, headscarf, Brahman turban, and shoes. The women dress like Brahman women, in a robe and bodice. Children go naked till four or five. After five a boy wears a loincloth, and a girl a petticoat and bodice. Both men and women are neat and clean but are not tasteful in their dress and have no special liking for gay colours. Most of them have a fresh set of clothes for special occasions, a rich robe and bodice worth £2 to £6 (Rs. 20 - 60) which last for several years. They wear head, ear, nose, arm, and foot ornaments. They are sober, thrifty, hardworking, even-tempered, hospitable, orderly, and clever workers. They follow a variety of callings, making cloth-scabbards, and khogirs or pad-saddles and charjamas or cloth-saddles, but not leather saddles. They make boxes and cradles, carve stones, paint and make figures of clay and cloth, pierce metal and paper plates, carve wood, make and repair padlocks, make and repair tin brass and copper pots, make gold and silver ornaments, cut diamonds, and make vinasor lyres and sarangis or fiddles and other musical instruments. Their women and children help in their work. Their children begin to work at seven and are skilled workers by twenty. If the boy belongs to their own caste he is expected to know something and is paid 16s. to £1 (Rs. 8-10) according to the amount he does. If the boy belongs to another caste, from whom the workman does not expect much help, beyond blowing the fire and handing him articles, the boy is paid 2s. to 8s. (Rs. 1-4) a month, but if he proves intelligent and useful his wages are raised to £1 to £1 4s. (Rs. 10-12) a month. A skilful workman seldom serves under another man. He opens a shop or works in partnership with his master. The Arya Kshatris always work to order, and keep no ready made articles in stock. The merchants who want the articles give them the metal agreeing to pay them at so much a pound. The yearly income of a working family, including a man his wife and two children, varies from £10 to £20 (Rs. 100-200). Their work is not constant and few of them have capital. According to their calling Jingars are known as Chitaris, Jades, Lohars, Nalbands, Otaris or casters, Patvekars, Sonars, Sutars, Tambats, Tarkars or wire drawers, and Tarasgars or scale-makers who eat together and intermarry. Besides receiving payment in cash they barter their wares for clothes and grain. They complain that the use of European and Australian copper sheets has taken from them part of their old calling, and, that since the 1876 famine, people have been too poor to paint their houses or to buy ornaments. They are somewhat depressed and some have sunk to be labourers. The uncertainty of their work and the large sums they spend on family observances have sunk some of them in debt. They have credit and borrow at one to two per cent a month. They claim to be Somvanshi Kshatris and their claim is supported by deeds or sanads given to them by the Shankaracharya of Shringeri in Maisur. The Arya Kshatris are Smarts and keep images of their gods in their houses. Their priests are ordinary Brahmans, generally Deshastha to whom they pay great respect. They keep the usual Brahmanic fasts and feasts, and make pilgrimages to Benares, Gaya, Jejuri, Shiv Kanchi, Tuljapur, and Vishnu Kanchi near Rameshvar, and Mukteshvar near Seringapatam. Their teacher or guru is Shankaracharya whose chief monasteries are at Shringeri and Sankeshvar. Every two or three years his followers make Shankaracharya a money present at 2s. (Re. 1) a year from each house. For her first child a young wife generally goes to her parents'. A room is cleaned, cowdunged, and furnished with a cot, and, when her time comes, a midwife is sent for, and the woman is taken to the lying-in room. The child is laid on a cloth on the ground and a hole is dug close by. The midwife washes the mother, cuts the child's navel cord, bathes the child in warm water, binds it in swaddling clothes, and lays it beside its mother on the cot. The hole is worshipped, betel and leaf packets are laid near it, and the navel cord and afterbirth are buried outside of the house. The lying in room is cowdunged and the mother's clothes are washed by the midwife. The mother is given a mixture of butter and assafoetida, and is fed on equal quantities of rice and butter.

The child's head is marked with sweet oil and it is fed by sucking a piece of cloth soaked in cow's milk. A lighted lamp is laid near the mother's cot, and, according to the custom of the family, either five wheat flour lamps are lighted and kept burning in the mother's room for five days or one on the first day, two on the second, and so on to five lamps on the fifth day. Some make no dough lamps, and content themselves with a single brass lamp. On the fifth morning the child is bathed and a handful of vekhand or orris root powder is rubbed on its head, a hood is drawn over its head, and it is laid beside its mother. A grindstone and roller are laid in a corner of the mother's room, and thirty-two kinds of healing plants, herbs, and roots are laid on the grindstone. A penknife is also laid on the stone and worshipped by the midwife, if she belongs to the mother's caste. If the midwife does not belong to the mother's caste the mother herself lays before the grindstone cooked rice, sugar cakes, and fire betel packets. A lighted lamp is placed near the grindstone and fed the whole night with oil. Of the five betel packets one is eaten by the mother and the four others are eaten by four young women, who keep watch the whole night over the mother and her child, playing with dice, odds and evens, and other games. Next morning some married woman or the midwife throws the dough lamps into a stream or river. The healing herbs are moved from the stone and given to the young mother. On the morning of the tenth the whole house is cowdunged, the mother and child are bathed, and ail her clothes and the cot are washed. On the morning of the eleventh day the house is again cowdunged, the mother and child are bathed, her cot and clothes are again washed, and the men of the family change their threads. From this day the mother is touched by the people of the house, but she is not pure enough to enter the cook room or offer cooked food to the house gods. On the twelfth day, five married women whose children are alive, wash the child's cradle, rub it with turmeric and redpowder, and hang it from one of the house rafters. On the ground below the cradle is placed a leaf plate with a handful of wheat and on the plate a lighted dough lamp. In front of the lamp on a betel leaf are laid boiled gram, and the five married women mark the cradle with turmeric and redpowder. They fill one another's laps with boiled gram, betelnut and leaves are served, and they go home. In the afternoon when the feast is ready, the five married women come with other guests who have been asked in the morning, and they dine and go home. In the evening women guests come with presents of caps, hoods, betel, rice, and dry cocoa-kernel. When all have come, a low wooden stool is set near the cradle, and the mother takes the child in her arms and goes and sits on the stool. The guests sit round her and the child's maternal grandmother fills the laps of women guests who do not belong to her daughter's family. The young mother's lap is filled by her mother or by a kinswoman, and copper anklets are put round the child's feet. The child's maternal grandmother marks her daughter's brow with redpowder and presents her with a bodice, fills her lap with rice and dry cocoa-kernel, and puts a hood on the child's head. The other women guests follow her example, presenting the child and mother with clothes, and filling the child's mother's lap. Then the child's father's sisters stand on each side of the cradle, dress a piece of sandalwood in a hood and child's other clothes, and pass it from one to another singing songs. The child is treated in the same way as the piece of sandalwood. It is then laid in the cradle and two women one after the other cry out kur-r-r in the child's ears, and slap each other gently on the back. Then a song is sung by the women guests, sugar and betel are served, and the guests withdraw. On a lucky day, in the third month, if the child is a boy, his head is shaved. In the morning on or below the veranda of the house a low wooden stool is set and on the stool is spread a piece of bodice cloth or cholkhan sprinkled with grains of rice. The child's maternal uncle takes the child on his knee, sits on the cloth, and, while musicians play, the barber cuts the child's hair with a pair of scissors leaving a top and two ear tufts. The uncle leaves his seat with the child in his arms, and, seating the child on another stool, rubs it with fragrant oil and five married women bathe it in warm water and rub its brow with redpowder. It is then dressed in its best clothes, ornaments are put on, and it is seated on a stool. The guests present the child and its mother with clothes. The barber is given the piece of cloth on which the uncle sat while the child's hair was being cut, ten copper coins, a betel packet, and uncooked food. The child is taken to the village temple with women guests and musicians, the god is presented with a copper coin and a betel packet, they bow to him and withdraw. A feast is held and the guests go home. When the boy is two or three years old comes the top-knot keeping. In the morning a low wooden stool is set on the veranda covered with a piece of bodicecloth, grains of rice are sprinkled over it, and the boy is seated on it and held from behind by his father. The barber shaves the child's head and the two ear tufts but leaves a round top-knot. The child's body is rubbed with fragrant oil and he is bathed. A new cloth is wound round his waist and he is carried into the house where he is dressed in rich clothes and taken to the village temple with women guests and music. A copper coin and a betel packet are laid before the god and they return to the child's house. Married women are presented with turmeric and redpowder, and a feast is held when a couple of sweet dishes are prepared and the guests withdraw. When the boy is between seven and nine the boy's father asks the village astrologer to fix a lucky time for performing the thread-girding. The astrologer names a day, and the father goes home, tells the house people what the astrologer said, goes to the market, and, for luck buys 1s. (8 as.) worth of turmeric root and 6d. (4 as.) worth of redpowder. On a lucky day three to five handmills are set in the house. To the neck of each, in a piece of yellow cloth, are tied a turmeric root, a few grains of rice, and a betelnut. Five married women who have children alive are called and asked to grind a handful of turmeric, and they grind it singing songs. After the turmeric has been ground inter powder it is poured into a metal pot; the grinders are presented with turmeric and redpowder, and return to their homes. The house people set to making preparations buying grain, butter, oil, molasses, and clothes A booth is raised, and, in a yellow cloth, a betelnut, a turmeric root, and a few grains of rice are tied to one of the booth posts which is called muhurtmedh or the lucky post. The morning before the day fixed men and women, with the family priest and music, go to the houses of relations, friends, and neighbours, and to the village god asking them to come next day to the thread-girding. After they return the marriage god or devak is installed as among Brahmans. In the evening an altar is raised by the housepeople measuring five and a half spans broad by the boy's hand and nine spans long and whitewashed. On this day all married women of the caste and boys whose munj or grass thread has not been taken off are asked to dine. Early on the thread-girding morning the boy's parents bathe, and a barber is called. The priest asks the barber to bring the razor with which he is going to shave the boy's head. The barber takes the razor out of his leather bag and lays it on the ground. The priest mutters verses over it, throws a few grains of red rice over it, and, taking it in his hands, cuts a strand of the sacred thread with it, as if to test its sharpness, and, with another blade of sacred grass, draws lines over it and gives it back to the barber. The boy is seated on a low wooden stool,, and the barber shaves his head except the topknot. The boy is bathed, his brow is marked with red sandal powder, and he dines from the same plate with his mother in company with married women and boys who have not ceased to wear the munj or grass cord. When his meal is still unfinished, the boy is made to leave the dining plate, his hands and mouth are washed, and he is seated in front of the barber. The barber again shaves the boy's head except the topknot, and a married woman rubs him with fragrant oil, bathes him, marks his brow with red sandal, and seats him on a stool near his father. The priest repeats verses, sprinkles water on the boy's head from the point of a blade of sacred grass, gives him a silk loincloth to wear, and blesses a sacred thread and puts it round the boy's left shoulder so as to fall on his right side. The priest holds in his hand a pimpal Ficus religiosa staff or dand, three feet nine inches long, to which is tide another loincloth and stands facing the boy. The boy is made to stand on the low wooden stool on which he had been sitting, and the men and women stand round the boy with grains of rice in their hands. A cloth is held between the boy and the staff, and the priest repeats verses. When the verses are over, the cloth is pulled to one side, and the boy is seated on his father's lap, who eleven times over whispers the gayatri or sun-hymn in the boy's right ear. The boy takes his seat on the altar, lights the sacrificial fire with the help of the priest, and feeds it with clarified butter, sesamum seeds, and parched rice. Next the boy comes off the altar and stands close by on a low wooden stool, a cord of twisted sacred grass is tied round his waist, and another along with the sacred thread, is put round his shoulders. He takes the staff or dand in his hands, walks into the house, makes a bow before his house gods, comes out, and he is again seated on the altar along with the priest. Married women bring sugar balls and lay them on the altar, and every one present, men women and children, takes in his hand a ladle to which a lucky thread or mangalsutra is tied, puts a sugar ball and a silver or copper coin into the ladle, and when the boy calls Om bhavati bhikshan dehi, Give alms, oh lady, in God's name, rolls the coin out of the ladle into his bag. The money is gathered, a few coppers are added, and the whole is divided into two equal shares, one of which is given to the priest and the other is divided among the Brahman guests. After this the boy dines and the priest is given uncooked food or shidha and 6d. (4 as.) in cash. The priest also gets a further fee of 3s. (Rs. 1½) in cash. The guests then feast on sweetmeats, betel is served, and they withdraw. At five in the evening the priest goes to the boy's, seats him on a low wooden stool, teaches him the prayer or sandhya, and continues to come and teach him every day till he learns it. On the second day nothing particular is done and on the third day the sacrificial fire is put out. In the morning of the third day the boy is bathed and seated on the altar close to the priest. The priest repeats verses and the boy feeds the fire with butter. Then water mixed with milk is sprinkled on the fire to put it out or as they say to make it calm orshant. The Brahman is given uncooked food and a couple of annas. A dish of cakes is prepared and eaten in the house. The guardian gods are bowed out and the booth is pulled down, and if the boy's family deity is a goddess a gondhal dance is performed. From the Gondhli's house a broad hollow pipe or chavandka is brought and worshipped along with the family gods and cooked food is offered to them. A few married women and the Gondhlis are feasted. The dancers bring with them two bags or jholis, three baskets or kotambalis stuck all over with cowrie shells, and a metal lamp or divti which they call the goddess Amba Bhavani. These are placed in a line on the ground and the boy's father bows before them, and, on five betea leaves, lays all kinds of food cooked in the house. The guests including the dancers dine, betel packets are offered them, and the married women and the dancers are each presented with a copper coin. They retire leaving the goddess that is the lighted lamp in the booth. About nine or ten at night the dance is begun and the Gondhlis go on dancing and singing till six next morning. At the the end of the dance the dancers are presented with an old turban or robe and a rupee in cash, Then comes the munj loosening or sodmunjwhich takes place from the fifth day to two, three, or six years after the thread-girding, but always before the boy's marriage. On the morning of the munj loosening a barber is called, and the boy's head is shaved, and he is bathed by married women. The cords of sacred grass which at the thread-girding were tied round his waist and shoulders are brought from the place where they have been kept, and are tied round his waist and shoulders as before. A sacrificial fire is kindled with the help of the Brahman priest and fed with butter and parched rice. The boy leaves his seat and sits close by on another low wooden stool. He is dressed in a waistcloth, turban, coat, and shouldercloth, lampblack is rubbed on his eyes, shoes are drawn over his feet, a walking stick and an umbrella are put in his hands, a bag of rice is laid on his right shoulder, and he is told to ask leave of all present to go to Benares to study the Veds. He asks leave to go. H they agree he walks a few paces, when his maternal uncle stops him, begs him to give up the idea of an ascetic life, and to return, marry his daughter, and lead the life of a householder. The boy comes back and makes over the bag to the priest with about 1s. (8 as.) in cash. The priest is given uncooked food, and the day ends with a feast. A'rya Kshatris marry their girls between five and eleven, or, on pain of loss of caste, at least before they come of age. Boys may be married at any time and are generally married between twelve and eighteen. The parents limit the choice to families of the same caste, and, among castefellows, to families of a different stock or gotra. In families who have a young daughter the women of the house consulting with the men fix on some boy as a good match for their daughter. The girl's father goes to the boy's house, and, after dining, stands on the veranda, looking for a passer-by. He accosts one, and asks him to intercede on his behalf, as he has come from his own village in the hope of getting the son of the owner of the house to marry his daughter. The stranger agrees, leaving any work however urgent, as the helper of a marriage gains merit. He walks in and asks the householder to come out. The three seat themselves on a blanket or carpet, and the go-between explains to the host the object of the guest's visit. He praises the guest and his family and declares that his daughter is healthy handsome and wise. The householder says he does not wish his son to be married, times are hard, and he must consult his people. After much persuasion and flattery, the householder agrees, but says he must first see the girl and decide whether she is suitable for his son. The guest asks the householder to call his son. When he comes, the guest asks the boy his name and his family name, puts him several questions, asks him to show his copy and study books, makes him read and write a little, shows him a picture or a drawing and asks him what fault it has, and if the boy can draw asks him to show some of his work. After having satisfied himself the guest asks the host to fix a day on which he will come to the girl's house to see her. A day is named and the girl's father and the go-between leave. The boy's father talks the matter over with his wife and other members of the house. He tells them he should much like to get his boy married daring his lifetime. On the day named he starts for the girl's house and puts up there. The girl is dressed in rich clothes, decked with ornaments, and brought forward and shown to the boy's father, and one or two relations or neighbours whom the girl's father has asked to be present. The boy's father, taking the girl by her hand, seats her on his lap, and, that he may see her more plainly, another person in front calls the girl and seats her on his lap. He asks her her name, and her parents' and brothers' names, and after a few more questions, she is told to bow before the boy's father and the rest of the company, and then walks into the house. Betel is served and the guests retire. If the boy's father approves of the girl a few Brahmans are called, and the boy's and girl's horoscopes are handed them and they compare them to see if they agree. If they agree the girl is called, and the boy's father presents her with a robe and bodice, she goes into the house and puts them on, and takes her seat as before. A packet of sugar is handed her which she takes, bows before them all, and walks into the house. The girl's father presents the boy's father with a new turban, betel is handed, and the guests prepare to leave. Before they go the boy's father asks the guests to wait for a short time, as he is anxious to settle some points before returning home. Then, either himself or some one on his behalf, asks the girl's father how much money he wishes settled on the boy and what clothes and ornaments he expects to be given to the girl. The girl's father says he is willing to give £2 10s. (Rs. 25) in cash as hunda or dowry and £5 (Rs. 50) worth of outfit or harni. After much haggling the cash and the outfit together are fixed at £10 (Rs. 100). Lists are made of things to he presented to the boy by the girl's father and to the girl by the boy's father, read, and handed to the fathers. [ The lists are to the following effect: Yadi or list of articles to be presented to the daughter of Ramchandra Babaji inhabitant of Sholapur by Govind Bapu inhabitant of Kolhapur, the boy's father, five chirdis or girls robes, fire cholis or bodices, thres turbans, three sashes, three rich robes, three common robes, one silver chain, one pair of silver feet chains or valas; one pair of silver toe rings or jodvis, one gold belpan and one gold kevda for the head, one putlyachimal or coin necklace, one pair of balis or earrings, nosering, and one pair of gold wristlets or patlis. Yadi or note of articles to be presented to the son of Govind Bapu inhabitant of Kolhapur by Ramchandra Babaji inhabitant of Sholapur, the girl's father, dowry or hunda Rs. 25 in cash, one silk robe, three waistcloths, eight turbans, eight sashes, three robes, three bodices, and metal vessels worth £1 (Rs. 10).] Then the Brahmans are asked to fix some lucky day for the marriage. After the marriage day or muhurt is fixed, sugar and betel packets' are handed and presents made to Brahmans. The boy's father is feasted and returns to his home. On his return he sets to work, buying grain, clothes, ornaments, and other articles required for the wedding. Red-sprinkled invitation cards are sent to distant kinspeople, and, if the boy's parents do not live in the same village with the girl's, the boy's people ask the villagers to come with them and they start so as to reach the girl's village at least a couple of days before the marriage. At the girl's village a house is hired for the boy's party, marriage booths are built at both houses, and an image of the god Ganpati is drawn under the front door of each house. When the boy's party comes close to the girl's village, they send a message to the girl's parents. In the evening a party start in procession with a gaily trapped horse and music, and seating the boy on the horse, bring him to his lodgings, followed by a number of carts containing guests, furniture, and clothes. This procession is called varkad or marriage. The house is lighted and the guests are seated, and, when betel has been served, they are taken over to their new lodging, shown the rooms, where to store their goods, and where to cook, sleep, and sit. A cook is sent to the boy's lodgings with uncooked dishes, and, after they are cooked, the guests are feasted, one of the girl's party acting as host. The invitation to the village god and other guests, the installation of the marriage gods, and the simant pujan or boundary worship are the same as among Komtis.