Delhi: Assembly elections

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

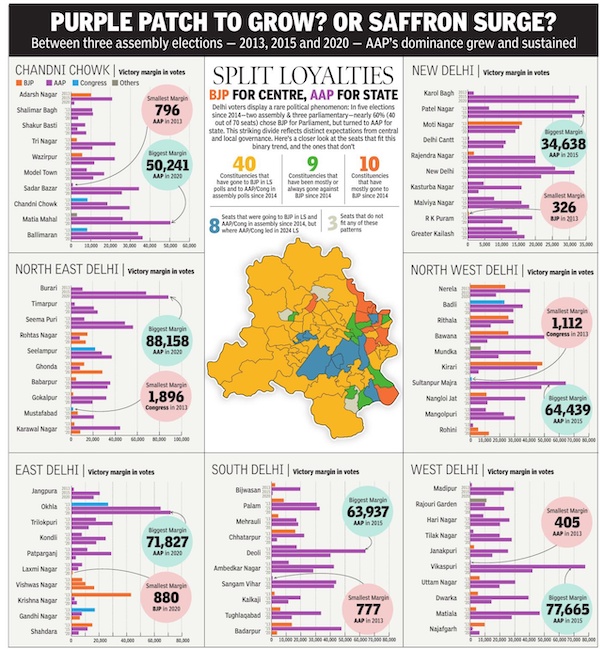

Margins of victory

Constituencies 2013, 2015, 2020

From: Feb 5, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

The five constituencies with the highest margins of victory in the Delhi Assembly elections in 2013, 2015, 2020

Number of candidates

1993-2020

Atul Mathur , January 25, 2020: The Times of India

From: Atul Mathur , January 25, 2020: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: With 668 candidates left in the fray, the 2020 Delhi assembly polls will witness the lowest number of contestants fighting for 70 seats since 1993, when the first election of the reconstituted assembly was held.

The Delhi election office had received 1,528 nominations from 1,029 candidates (one candidate can file up to four applications) till January 21, the last date of filing nominations. After the scrutiny of documents on January 22 and 23, the election office found 698 nominations valid to contest the polls. On Friday, the last date of withdrawing nominations, 30 candidates opted out leaving 668 candidates to battle it out.

In 1993, a record 1,316 candidates had contested the elections, but the number decreased in subsequent polls. In the 2015 assembly polls, 673 candidates — 606 men, 66 women and one transgender — had been in the fray. The gender-wise break up of candidates this year was not known till filing of this report.

However, the three major political players — AAP, BJP and Congress — have collectively fielded 24 women candidates this year. While Congress has given tickets to 11, eight are contesting from AAP and BJP has fielded five. In 2015, BJP had fielded eight, AAP six and five had contested on the Congress symbol.

Among the prominent candidates who withdrew their nomination on Friday, two were incumbent MLAs from AAP — Mohammed Ishraq (Seelampur) and Jagdeep Singh (Hari Nagar) — and former Congress legislator Asif Mohmmad Khan (Okhla). The three had filed their nominations as Independents after their respective parties denied them tickets.

The nomination of former SAD MLA Jitender Singh Shunty, who had filed his nomination as BJP candidate from Shahdara assembly segment, was rejected on Thursday due to technical deficiencies. SAD is not contesting the polls this year.

Late on Thursday, the election office had released the break-up of the total voters. A record 1.47 crore voters in the city of over 20 million are eligible to cast their votes this year with the ratio of 73.4 electors per 100 people. There are 824 women per 1,000 male voters this year compared with 819 in the last assembly polls. In 2015, 1.33 crore people were eligible to cast their votes, but only 67% had exercised their franchise.

Matiala in west Delhi has the highest number of over 4.2 lakh voters, followed by Vikaspuri (4 lakh), Burari (3.6 lakh), Okhla (3.3 lakh) and Badarpur (3.2 lakh). Chandni Chowk is the smallest constituency in terms of voters with just over 1.2 lakh voters, closely followed by neighbouring Matia Mahal and Delhi Cantonment. Balliamaran and New Delhi are the fourth and fifth smallest assembly constituencies with over 1.4 lakh voters each.

Strike rate

1993 – 2020

From: January 29, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

The ratio of the number of seats won to seats contested by the main political parties in Delhi, 1993 – 2020

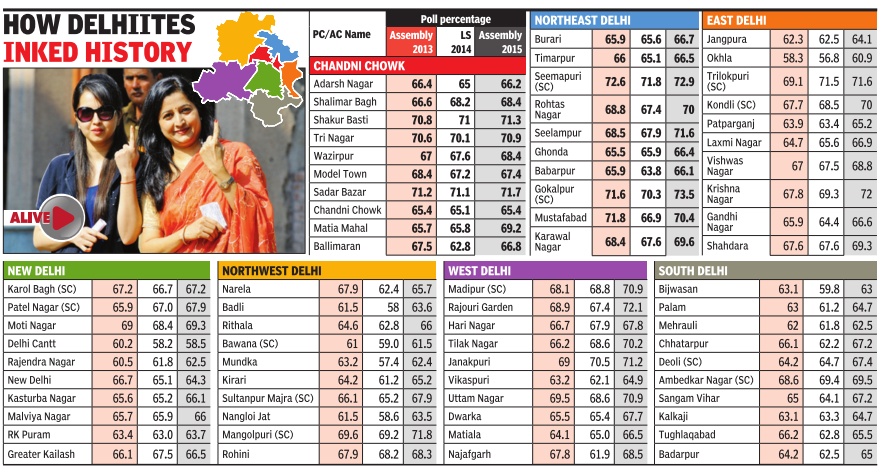

Voter turnout

1951-2020

From: February 9, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

Voter turnout in elections to the Delhi legislative assembly, 1951-2020

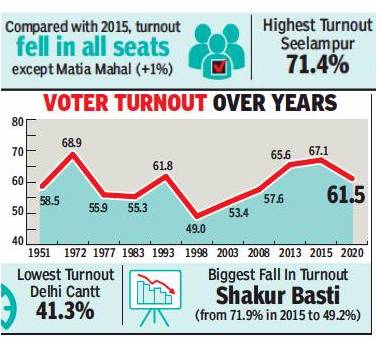

2020: Constituency-wise turnout

From: February 10, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

2020: Constituency-wise turnout in the Delhi assembly elections

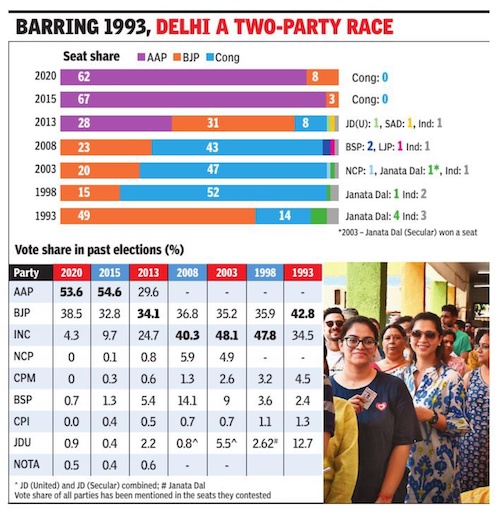

1993-2020

Atul Mathur, January 20, 2025: The Times of India

From: Atul Mathur, January 20, 2025: The Times of India

From: February 3, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

Delhi assembly elections: the Vote share of political parties, 1993-2020

New Delhi : They once posed a challenge to the dominance of Congress and BJP in the electoral politics of the capital. However, several prominent national and state parties, which even won a few seats in different elections, slowly faded away in ignominy and have no relevance left in the city politics now.

The unrecognised registered parties, which have also been a regular feature in all Lok Sabha, state assembly and municipal polls over the years, too, have failed to rise beyond being just a statistic in the reports prepared by Election Commission after the conclusion of the exercise.

Delhi’s electoral politics, which has always been known for the dominance of two political parties, continues to remain the same – only a player has changed in the equation in the last decade. While it was Congress and BJP earlier, the emergence of AAP in 2013 changed the dy- namics. The rise of the Arvind Kejriwal-led party not only led to the decimation of Congress, with the core voter base of the grand old party shifting its loyalties to the then political greenhorn, but the small vote banks of other national and state parties also gravitated towards AAP.

As a result, a majority of votes polled in the last few years either went to BJP or AAP, depending on whether it was the parliamentary election or the assembly polls, while only a fraction came to the kitty of the remaining players in the fray, including independents.

The election of 1993, first after the reconstitution of Delhi legislative assembly, saw six national, three state, and 41 registered unrecognised parties throwing their hats in the ring. While three parties – BJP, Congress and Janata Dal – nominated candidates on all 70 seats, most chose to contest in a select few constituencies. A total of 1,316 candidates, including 766 independents, were in the fray. While six national parties together polled 90.6% of votes, the three state parties got a meagre 2%, registered unrecognised players barely 1.3% of votes, while all independent candidates together got a vote share of 5.9%. Of the six national parties, BJP and Congress got 42.8% and 34.5%, while Janata Dal got 12.7%, and the remaining three got a meagre 0.8% of votes. While Janata Dal managed to win four seats, three independent candidates were also elected. The city, which has nearly 17% of Dalit voters, with 12 of 70 seats reserved for them, and having the power to tilt the election outcome in another 5-7 constituencies, saw the rise of Bahujan Samaj Party in the subsequent polls. From 1.9% in 1993, the party’s vote share increased to 3.6% in 1998, and 9% in 2003. The year 2008 saw BSP putting up its best-ever performance by winning a healthy 14.1% of votes and two seats in the assembly. The rise of AAP, which grew as a messiah of the poor in 2013, saw a sudden drop in the popularity and support of all smaller parties. In 2015, AAP, BJP and Congress together polled 97.1% of votes while the remaining four national, nine state, 53 registered unrecognised parties and 195 independent candidates together got 2.9% of votes. The situation was similar in 2020, when AAP, BJP and Congress secured 96.6% and the rest of the players got the remaining 3.4%.

Ravi Ranjan, a professor of Political Science in Delhi University’s Zakir Husain Delhi College, said the prime objective behind forming a political party was to be active in electoral politics and show that they were serious players in this business. “Every political party, whether it is a national or a state player or an unrecognised group registered with Election Commission, has to show the world it is actively engaged in politics and that’s why they participate in the electoral process, despite knowing the possible outcome fully well,” Ranjan said.

“Also, all political players aspire to be known as state or national-level parties, for which they have to contest elections and get a certain percentage of votes as fixed by EC. It is a statutory requirement. If you don’t fight an election, where and why will these parties get the funding from their sponsors?” he added.

While prominent national and state parties genuinely try to spread their wings in other states and contest to make a difference, experts believe on many occasions the candidates of registered unrecognised parties and independents are used by bigger political players to “cut” into the votes of the rivals. “Often, the candidates of a particular religion or caste or affiliation are put up to confuse voters. Candidates with similar-sounding names of a prominent one in that particular constituency are also made to contest. If there are a number of candidates in a particular constituency with different symbols, the voter may get confused and votes might get divided,” said a veteran political functionary who worked as a back-end resource in a large number of elections.

Delhi as a whole: 1993-2025

From: Atul Mathur, February 9, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

The vote share of the main parties in the Delhi Assembly elections, 1993-2025

YEAR WISE DEVELOPMENTS

1993-2020: The two top parties

Atul Mathur, January 8, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

The two parties that pulled the highest number of votes in Delhi Legislative Assembly elections, 1993-2020

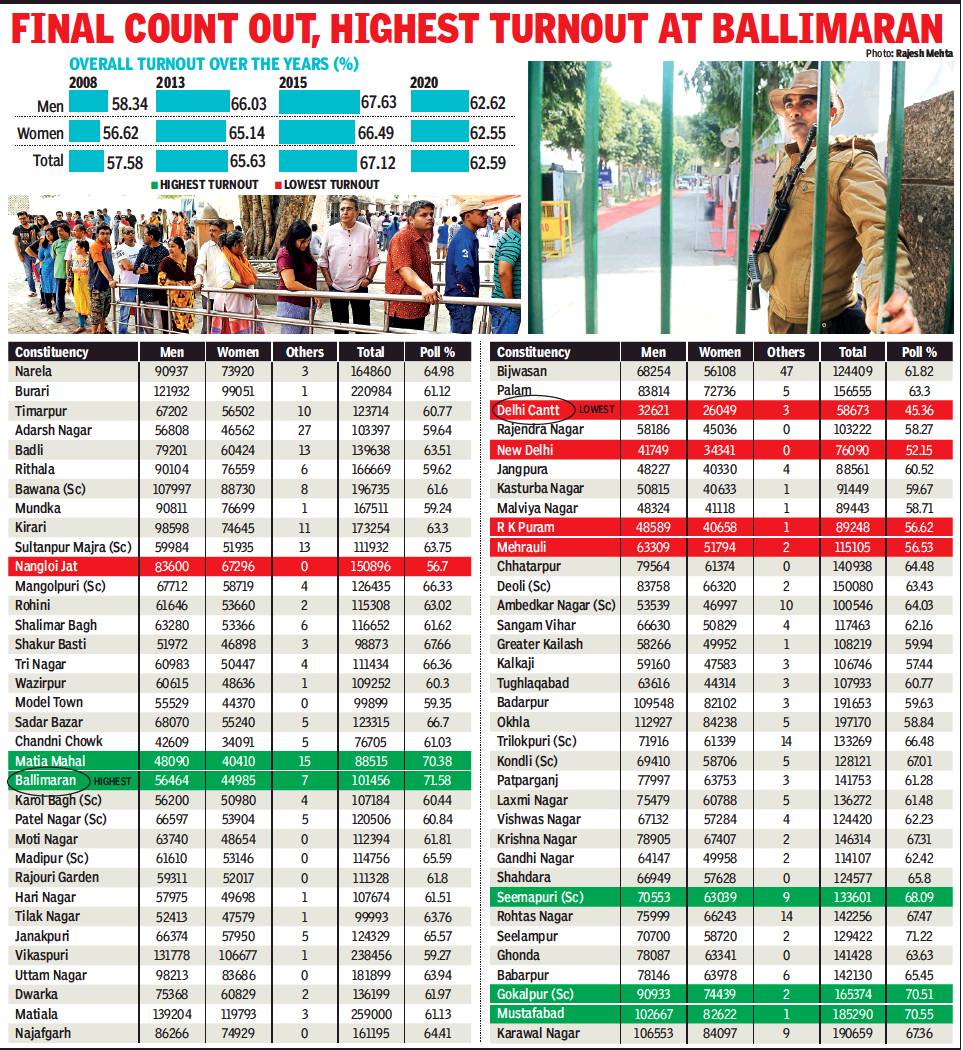

2013, 2015, 2020: voting patterns

From: Abhinav Rajput, January 8, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

2013, 2015, 2020: voting patterns in Delhi

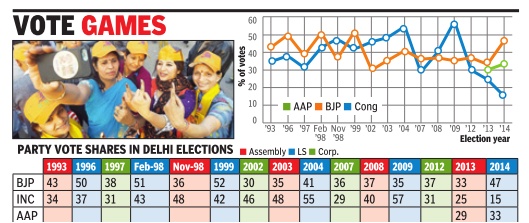

1993-2014: Shifting political loyalties

Vote pattern: How Delhi has been the sultan of swing

Subodh Varma The Times of India

Between 1993 and 2014 Delhi voted for 16 times . That's an election almost every 16 months.Starting 1993, there've been six Assembly elections (1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2015), six LS polls (1996, 1998, 1999, 2004, 2009 and 2014) and four civic elections (1997, 2002, 2007 and 2012).

A look at the vote shares of parties over these 16 elections shows a seeming unpredictability and a tendency to flip parties. This isn't evident if you look at only one type of election, say assembly or corporation. Put all elections together and it shows.There's a desire to change, perhaps even to punish. Hubris doesn't go down well with Delhi, especially if it accompanies non-performance.In this heavily politicized city, the educated and young electorate makes the distinction between requirements of different levels of government.

Between 1993 and 1998, voters gave a long rope to the rising BJP . They won the first 1993 assembly election, got majority votes in 1996 LS, won the 1997 corporation and majority in the 1998 LS polls which saw the shortlived NDA government emerge at the center.

Then, something snapped.After giving over 50% votes to BJP in the February 1998 LS elections, Delhi switched. The same November, it defeated BJP in the state elections, giving Shiela Dixit-led Congress their first government.

Months later, in 1999, Del hi again voted BJP in the LS elections. Vajpayee formed government at the Center.Three years later, in the 2002 civic polls, Delhiites defeated BJP and brought Congress.Next year, they again voted Congress in the assembly .Then, in the 2004 LS polls, the Capital went with Congress, giving them over 55% votes.

Three years later, Delhi tired of Congress and voted BJP back into the corporation. But in the 2008 assembly, Congress won a record third time. The Congress honeymoon continued in the 2009 LS elections, the party getting 57% votes. It took three years for another switch to happen--BJP won the 2012 civic polls.

This switching around might seem fickle. Actually , it's a flailing between the two options available. In a two horse race, Delhi-wallahs exercised the whip to punish non-performance. Finally , in 2013, hubris met its nemesis. The two dominant parties that had, between them, ruled Delhi at all levels for two decades faced a challenger, Aam Aadmi Party .BJP , which was again rising, had expected a rebound from the moribund Congress but AAP walked away with over 29% votes and Congress dipped to its all-time low of 25% vote share in the Assembly elections.

Knowing that AAP wasn't a serious contender for the Centre, and tired of Congress, Delhi voted BJP in 2014 LS, giving it 46% votes. AAP increased its vote to 33%. Congress plummeted to an alltime low of 15%.

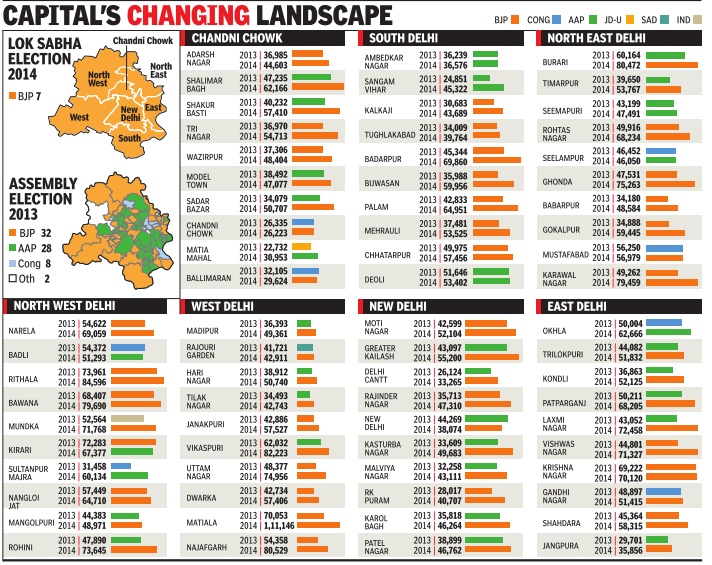

2013 and 2014: Political changes

See graphic 'Delhi:Assembly elections:2013, Lok Sabha elections:2014'

2020

AAP Proves It’s Bullet-Proof In Delhi, February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: AAP Proves It’s Bullet-Proof In Delhi, February 12, 2020: The Times of India

Rarely has an election to a small state assembly of 70 seats generated as much nationwide interest as Delhi’s. Bitterly contested under the shadow of the two-month-long anti-CAA protests at Shaheen Bagh, violence on campuses, chants of “goli maaro” at a Union minister’s rally, and gunfire, it was billed by many as a virtual referendum on nationalism. But Arvind Kejriwal’s aim never wavered as he stayed focused on AAP’s track record — while BJP missed the target yet again, and Congress fired a blank

In Another Landslide, Kejriwal Sweeps 90% Of Seats; BJP Fails To Reach Double Digits

Winning by a landslide in a fiercely competitive arena is no mean feat, but pulling off an encore is nothing short of a miracle. The Arvind Kejriwal-led AAP stunned the nation on Tuesday when it beat back an aggressive BJP to sweep the Delhi polls, winning 62 of 70 seats, a strike rate of 90%. AAP’s tally was just five seats short of 2015’s and its vote share fell by less than a percentage point – and this was in the face of incumbency. The brute majority and transformation of Kejriwal from an insurgent who gatecrashed Delhi’s political arena seven years ago into the city’s undisputed political boss will help restore his status as an important satrap among anti-BJP players. Unlike five years ago, when he had a support cast, AAP’s campaign this time was Kejriwal’s solo play.

For BJP, it is another setback. Though Kejriwal had widely appeared to be the overwhelming favourite, the saffron party, which had routed AAP in the Lok Sabha elections in May last year, had launched a no-holds-barred campaign spearheaded by its master strategist, home minister Amit Shah. Shah’s gambit in “nationalising” the local contest by focusing on CAA worked only partly. It helped raise the party’s vote share by 6.4 percentage points but could not stave off the embarrassment of finishing with a single-digit score for the second time running. It extended the run of disappointing shows for the BJP in assembly elections — in the 10 before Delhi, it formed governments in only Arunachal and Haryana.

Congress fared worse, drawing a blank yet again and lost its deposit in 63 of the 66 seats it contested — a stunning fall for a party which won three consecutive state elections and was in office until six years ago. The party’s vote share plunged to 4% from 9.7% in the last assembly election and will strengthen doubts about its viability as a contestant, with Delhi appearing set to join the growing list of geographies where it has been reduced to inconsequence.

AAP’s victory owes itself to the lure of freebies — power, water and transport — which helped it draw support from the grateful throngs in slum clusters and irregular colonies, besides its performance in public education and health. Kejriwal’s image was a big advantage that got stronger because of BJP’s inability to project a CM face. Congress’s continuing marginalisation helped, given the overlap between AAP’s supporters and what once used to be Congress’s constituency. The return of some erstwhile backers to Congress had seen AAP sliding to the third spot in the LS elections, but clearly it’s recovered from that setback.

Kejriwal ran a smart campaign, staying focused on his message of “development”, dodging BJP’s effort to lure him into taking a stand on CAA, and declining to join issue on other contentious issues such as his refusal to give sanction for prosecution of Kanhaiya Kumar and Umar Khalid for allegedly raising “tukde tudke” slogans at JNU.

Kejriwal evaded BJP’s effort to pit him against PM Modi

Faced with BJP’s highpress “nationalism” manoeuvre, Kejriwal swiftly improvised and cast himself as a “Hanuman bhakt” and a “hardcore nationalist”.

It was a smart counter-measure which de-ideologised the battle just when Shah’s campaign against the Shaheen Bagh protests had appeared to find resonance among significant sections of the majority community, raising the prospect of polarisation along communal lines. The advantage so gained was multiplied by the fact that Kejriwal’s status as the BJP’s sole challenger ensured him the support of the minority community.

In another midway switch, AAP’s tacticians launched the new “Dilli mein toh Kejriwal” campaign line to frustrate BJP’s attempt to pit him against PM Narendra Modi. Instead, he targeted local BJP leaders, converting the elections into a duel where he appeared to be “Dilli ka dabang” who dwarfed an assembly of saffron lightweights.

It was crucial because besides the message of nationalism and Modi’s appeal, BJP had little else going for it. The state unit had been in disarray with the ego conflicts among its leaders defying Shah’s attempt to knock them into a team. After its success on all seven seats in the LS elections, the party frittered away crucial time in waiting for the leadership to name its choice for CM, thus losing the psychological advantage it could have potentially had over AAP. It looked clueless when Kejriwal sought to recover lost ground by announcing freebies and launching an unprecedented publicity blitzkrieg. Shah taking charge did help restore morale and energised the cadre to put up a fight, but by then Kejriwal had already sprinted away. The failure of the three BJP-run corporations to perform only added to the lustre of Kejriwal’s “Acche beete 5 saal” plank.

Congress put in no effort at all despite the fact that unlike Kejriwal it had taken a strident stand against CAA. Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi Vadra put in perfunctory campaign appearances, leaving a lacklustre unit to fend for themselves. Post-dr ubbing, some leaders said the “no-show” was tactical as it did not want anti-BJP votes to split.

Shaheen-Jamia seat gives AAP huge win

AAP’s Okhla legislator Amanatullah Khan notched the second biggest win of the assembly elections, beating the BJP candidate, Braham Singh, by 71,827 votes. The MLA’s constituency includes Shaheen Bagh and Jamia, both centres of anti-CAA protests which had become a major election issue. Khan bettered his winning margin from 64,532 votes in 2015, and cornered over 66% of the votes polled.

List of victorious candidates

February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

Candidates who elected as MLAs in the Delhi assembly elections, 2020

Cong loses deposit in 63 of 66 seats

In the 66 seats it contested, Congress lost its deposit in 63, Badli, Kasturba Nagar and Gandhi Nagar being the exceptions. Its ally, RJD, too lost its deposit in all the four seats it contested. The Congress vote share of 4% was less than half the 2015 figure and a shocker for a party that had won the 2008 assembly polls with 40%. It was also a steep fall from the 22.5% vote share it had got in Delhi in the Lok Sabha polls last year.

What worked & what didn’t

February 12, 2020: The Times of India

What Worked For AAP…

AAP had an incumbent CM and charismatic leader in Arvind Kejriwal, who connects with citizens across all segments. He remains the preferred choice in the city’s jhuggis and unauthorised colonies despite BJP inroads. A leader who earlier evoked sharp reactions, he has tamped down on his combative instincts, reaching out to Congress and BJP voters as a “Dilli ka aam aadmi”

Populism played a role, with ‘zero’ electricity and water bills becoming a huge hook for voters, even those in middle-class colonies. The decision to make bus travel free for women was another such decision. The success of these measures makes it evident that the era of freebies is far from gone and will remain a significant lure for voters

AAP’s governance record has been patchy on issues like adding buses, dealing with pollution or funding the Metro, but it has scored on health and education. Its schools are seen to have improved with better teacher-student engagement. The mohalla clinics are an accessible option for the poor in need of medical assistance. Voters appreciated the effort even if the schemes are still works in progress

... & What Didn’t For BJP & Cong

BJP has found Delhi a bridge too far, unable to regain its glory days. The party’s organisational set-up remains a mess, its leaders are a fractious lot, and the emergence of a new crop is overdue. BJP’s record after winning the 1993 assembly election has been poor and its effort to regularise illegal colonies came too late to convince this chunk of voters to switch allegiance

Congress’s revival of sorts in the LS polls where it came second in vote share proved passing. In the absence of a forceful leader such as Sheila Dikshit, the party floundered, its stagnation worsened by an indecisive central leadership which fell back on old-timer Subhash Chopra. Its fall to less than 4.5% of the vote was a big factor in AAP warding off the BJP challenge

The fate of defectors

Atul Mathur, February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: Atul Mathur, February 12, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

How candidates who defected from one party to another fared in the Delhi assembly elections, 2020

2025

The overall results: statistics/ 2025, also 2015, 2020

February 9, 2025: The Times of India

From: February 9, 2025: The Times of India

The saffron outfit’s last and only stint in office in NCT Delhi had come in 1993, nearly two decades before Arvind Kejriwal launched his party

What made BJP win, AAP lose

February 9, 2025: The Times of India

BJP-AAP vote share gap is quite small. So, what swung the election decisively in BJP’s favour? Some short takes:

SAFFRON’S LONG MARCH: BJP’s campaign for Delhi started much before polls were announced. Every bad headline against AAP was followed by a sustained BJP campaign, hurting the incumbent. Closer to elections, ‘sheesh mahal’, as BJP cleverly named the generously refurbished CM residence, hurt AAP’s image even more. After initially criticising AAP’s freebie game, BJP, too, made populist promises with gusto. BJP also talked up the idea of a double-engine sarkar, even as perceptions of govt dysfunctionality took hold, in part thanks to the LG-AAP fight. By the time polls were held, many voters had bought BJP’s argument

TAKING THE MIDDLE OUT: Vote-share stats make it clear AAP has lost little of its core low-income vote. BJP would have always strategised with that assumption — and therefore it targeted Delhi’s neo-middle class and middle class, who were more upset with the state of roads, traffic, Yamuna, and air pollution than they were impressed by free water, power and primary health care. To that, BJP added the announcement of the 8th Pay Commission — Delhi voters include many govt employees and their families — and the Budget’s income tax cuts

‘FAKES’ AMONG FREEBIES: BJP campaigned hard against some elements of AAP’s welfare policy regime. ‘Fake medicines’ and ‘ghost patients’ in free mohalla clinics was one such campaign. AAP contested these claims hotly. But some of those charges stuck when coupled with demonstrable failures like Yamuna flowing as dirty as ever and desperate AAP claims like Haryana’s BJP govt ‘poisoning’ Yamuna water. That AAP suffered big losses in seats along the Haryana border tells this story powerfully

BRAND KEJRIWAL LOSES SHEEN: Kejriwal started as a ‘humble man of the people’ who didn’t want to stay in govt bungalows. But he came into these polls as a very different leader. He and his colleagues didn’t recognise that aside from anti-incumbency against AAP, there was anti-incumbency against Kejriwal himself

MODI HAI TO… When things turned against AAP, Modi’s appeal, dormant in the last two assembly polls, came to the fore. He was front and centre in BJP’s campaign and his sharp attacks and promises of smooth coordination between the Centre and Delhi made an appreciable difference.

The main trends

Atul Mathur, February 9, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : BJP scored a spectacular victory in all parliamentary constituency areas to win 48 of the 70 assembly seats in the capital. In particular, it was the party’s performance in outer Delhi, areas bordering Haryana, that helped it rout AAP and storm back to power after 27 years.

AAP, for its part, continued its impressive run in Muslimand Dalit-dominated seats apart from winning isolated pockets with a higher number of JJ clusters and unauthorised colonies.

BJP triumphed in nine of the 10 seats in the West Delhi parliamentary constituency, eight each in North West Delhi and East Delhi and seven in New Delhi. The remaining seats came from Chandni Chowk, where six of its candidates emerged victorious, and five each in South Delhi and North East Delhi.

In the 2020 assembly polls, when BJP tallied just eight seats, the party had failed to win a single seat in New Delhi, West Delhi, South Delhi and Chandni Chowk. While one BJP candidate was elected from North West Delhi, three each returned from East Delhi and North East Delhi.

BJP, thus, not only made inroads in urban pockets of central Delhi and New Delhi this time, but also almost swept the outer Delhi areas and rural parts of the city. “Of the 13 seats that share a border with Uttar Pradesh, we got seven while of the 11 constituencies on the border with Haryana, we won nine,” smiled a BJP functionary.

Narela, Mundka, Badli, Najafgarh, Palam, Bijwasan, Matiala, Chhatarpur and Mehrauli were some of the prominent rural seats where BJP had failed to do anything impressive in the last two elections but where it performed extremely well this year. Surender Solanki, chief of Palam 360 Khap, said the rural voters came out in large numbers to support BJP. “The villages, be it rural or urban, were completely ignored by Delhi govt. We ran a campaign, visited every single city village, interacted with the residents and prepared a list of demands. We approached all political parties. While AAP continued to ignore us, the PM called us as did the Union home minister and assured us our issues will be addressed. The Khap, accordingly, supported BJP,” said Solanki. The Khap chief added that BJP managed to wrest several seats with the support of the villagers from AAP, which itself had grabbed them from Congress in 2013.

AAP held on to its support base in reserved constituencies. While the party had won all 12 SC seats in 2015 and 2020, it retained eight seats this time. Similarly, people came out in large numbers in constituencies dotted with unauthorised colonies in its support. Gokalpur, Ambedkar Nagar, Kondli, Okhla, Badarpur, Tughlaqabad, Deoli, Kirari, Burari and Sultanpur Majra are known for having large clusters of unauthorised colonies. An AAP functionary explained why. “In our campaign, we highlighted the work done by our govt to improve the amenities in the city’s 1,797 unauthorised colonies. We connected these colonies with sewer and water pipelines, laid down roads, built drains and improved overall living conditions. The support we got from the residents of some of such colonies is a validation of our work.”

While the Muslim vote showed signs of division in a couple of constituencies, it largely went in the favour of AAP, getting big victories for its candidates. Except Mustafabad, where the Hindu votes consolidated against a trifurcation of Muslims votes, AAP won comprehensively in Okhla, Seelampur, Matia Mahal and Ballimaran. It also performed reasonably well in areas where Muslims live in large numbers but are not the deciding force, such as at Kirari and Seemapuri.

Despite being the partners in the INDIA bloc, a gro- uping of opposition parties at the national level, AAP and Congress contested the assembly election separately. This was to BJP’s advantage. According to an analysis, there are 14 seats that BJP won because Congress garnered more votes than the margin between the winner and the closest rival. These seats are Timarpur, Badli, Nangloi Jat, Madipur, Rajendra Nagar, New Delhi, Jangpura, Kasturba Nagar, Malviya Nagar, Mehrauli, Chhatarpur, Sangam Vihar, Greater Kailash and Trilokpuri.

Some political observers believed that had Congress and AAP contested the election as alliance partners, the results could have been different. Although the vote cutting by Congress was evident in its candidates saving their security deposits only in Kasturba Nagar, Badli and Nangloi Jat, a Congress functionary refused to accept the theory. “We contested the Lok Sabha election jointly and the result was we failed to win a single seat. Theoretically, one can say that the alliance could have prevented the BJP juggernaut, but the results could have been totally different too,” the Congress member argued.

The fate of defectors

Sugandha Jha, February 9, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : Bets placed by 15 of the 24 candidates who switched parties before contesting the Delhi assembly elections didn’t pan out, but BJP gained the most from former AAP and Congress names in the capital’s three cornered fight. The most prominent among defectors was Kailash Gahlot, who was the minister for administrative reforms in the AAP govt, till he switched allegiance to BJP last year.

Gahlot, who previously represented Najafgarh constituency as an AAP MLA, contested from Bijwasan this time and won by 11,276 votes over his nearest rival Surender Bhardwaj (AAP). After his win, Gahlot said, “Delhi has reposed its faith in the vision of PM Modi. Bijwasan has pressing issues like water shortages and sewer infrastructure. I will ensure these are fixed.”

Other victories came from senior Congress faces who joined BJP.

Arvinder Singh Lovely, the former Delhi Congress chief, left the ‘grand old’ party after disagreements over ticket distribution.

Lovely, who had opposed Congress’s decision to field Kanhaiya Kumar from the capital in the 2024 Lok Sabha election, won Gandhi Nagar this election by a margin of 12,748 votes. AAP’s Naveen Chaudhary came in second. It was three-time Congress MLA from Jangpura, Tarvinder Singh Marwah, who defeated former deputy CM and Arvind Kejriwal’s trusted second-in-command Manish Sisodia, this time as a BJP contestant.

Though Marwah’s lead over Sisodia concluded at just 675 votes, this victory is a symbolic one for BJP. Marwah exited Congress in 2022 after publicly complaining that he was not given time for a meeting by the Congress high command. In Chhatarpur, it was a battle of defectors, which tilted in favour of AAP-turned- BJP politician Kartar Singh Tanwar. He trumped Brahm Singh Tanwar, who had gone the other way around.

Pravesh Ratn was one of the only two politicians who went from BJP to AAP, and won. He clinched the Patel Nagar reserved seat for the Kejriwal-led party, defeating AAP defector Raaj Kumar Anand.

The only other BJP defector to win as an AAP candidate was Anil Jha, who secured the Kirari constituency.

Of those to lose the polls were several AAP members who moved to the Congress. These included Asim Ahmad Khan (Matia Mahal), Devender Sehrawat (Bijwasan), Abdul Rehman (Seelampur), Mohammad Ishraque (Babarpur) and Adarsh Shastri (Dwarka).

Those who went the other way, from Congress to AAP, didn’t make headway either — Sumesh Shokeen (Matiala) and Mukesh Goel (Adarsh Nagar), for instance.

Still, the Aam Aadmi Party can take heart that not all was lost. Among them was Priyanka Gautam, who could not wrest SC-reserved Kondli constituency for the BJP from AAP’s Kuldeep Kumar, though he won by a lower margin this election. In 2020, Kumar had a lead of almost 18,000 votes over his nearest rival.

Gautam is a sitting councillor who won the 2022 MCD polls on an AAP ticket.

A big downer for AAP was from Timarpur, a constituency it has won the last three Delhi polls it contested.

Surinder Pal Singh, who was earlier in both Congress and BJP, had held the seat in 2003 and 2008.

He moved to AAP last Dec, but could not clinch a victory from Timarpur.

The seasoned politician lost to BJP’s Surya Prakash Khatri by just 1,168 votes in a contest overshadowed by allegations that 30,000 voter slips were found at a scrap dealer’s shop.

See also

Delhi: Assembly elections

Delhi: Assembly elections,2015

Delhi: elections-related issues