Depressed castes: Sholapur

Contents |

Depressed castes: Sholapur

This is an extract from a British Raj gazetteer pertaining to Sholapur that seems |

Depressed classes

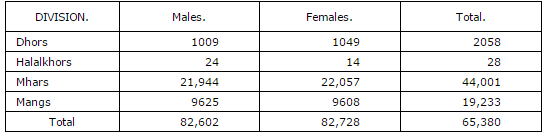

Depressed Classes include four castes with a strength of 65,330 or 12.13 per cent of the Hindu population. The details are:

Dhors

Dhors, or Tanners, are returned as numbering 2058 and as found over the whole distict. The founder of the caste is said to have been the sage Lurbhat who was born of an Aygav father and a Dhigvar mother. Their surnames are Borade, Katavdore, Khandore, and Sinde. They are divided into Maratha and Lingayat Dhors who do not eat together or intermarry. In each division families having the same surname eat together but do not intermarry. They are generally dark with round faces, thick lips, and straight black hair. The men wear the moustache and cut the head hair short. Both at home and abroad most speak Marathi, and the rest speak Kanarese at home. Their houses are generally ill-cared for, one storey high, with mud and stone walls, and flat roofs. A few live in thatched huts. They have a front veranda which is used as a shop. Their vessels are of metal and clay and they have cattle and a servant or two to help them. Their staple food includes jvari bread, pulse, and vegetables, and they eat the flesh of goats and sheep and drink liquor. Their holiday dishes of rice, wheat, and gram cost a family of five 1s. to 4s. (Rs. ½-2) and their caste feast cost £1 to £1 10s. (Rs. 10-15) the hundred guests. The men dress in a loincloth, a waistcloth, a turban, a waistcoat, a shouldercloth, and a blanket; and the women wear the robe and bodice in Maratha fashion. They have a spare suit of clothes for holidays and other festive occasions. They are hardworking and hospitable, but intemperate and dirty. They work in leather, cut and dye skins, make saddles shoes and water-bags, and till the ground. They are fairly off. They are religious and keep house deities, generally Bahiroba, Bhavani, and Khandoba. Their priests are the ordinary village Brahmans whom they greatly respect. They fast on every lunar eleventh and on Shivratra in February. The Lingayat Dhors who are a small body are invested with a ling by a Jangam soon after birth. Their teacher or guru who is a Lingayat visits them occasionally when each family gives him 2s. 6d. (Rs. 1 ¼) in cash. Some well-to-do families give more, and also hold caste dinners in his honour. Except the Lingayats, Dhors hold their women impure for ten days after childbirth. In their customs they differ little from Marathas. Their guardian or devak is formed of the branches of five trees or panchpalvis, which they tie to a post in the marriage booth. At the time of marriage the boy is made to stand on a grindstone and the girl facing him in a basket on a coil of thick plough rope, belonging to her father's field. A quilt is held between them, the Brahman priest utters some words and throws grains of rice over their heads, and they are husband and wife. They are then seated on an earthen altar in the marriage hall, and, to keep off evil, married women draw near and each in turn takes a few rice grains in her hands and throws them over the boy's and the girl's head, body, knees, and feet. The hems of their garments are knotted together and they are taken on a bullock to the village Maruti, and thence to the boy's. They allow widow marriage and practise polygamy. They either bury or burn the dead, and mourn ten days. The chief mourner shaves his moustache and the body is carried on the shoulders of two bearers in a blanket or coarse cloth slung on a pole. Lingayat Dhors as a rule bury the dead, do not shave the mourner's moustache, and observe no mourning. Their headman is called Mhetar and their social disputes are settled at caste meetings. They do not send their boys to school. They are well-to-do, living in comfort and laying by.

Halalkhors

Halalkhors, or Scavengers, are returned as numbering thirty- eight and as found in all municipal towns. They are Hindustanis and have come into the district since the establishment of municipalities for whom they work as night-soil men. They are tall dark and thin, and the men wear the moustache, beard, and whiskers. They speak Hindustani. Their houses are like those of poor cultivating Marathas, and they have metal and earthen vessels and cots. They keep cattle, sheep, goats, and fowls, and eat the flesh of sheep, goats, fowls, cows, and hares, and drink liquor. A family of five spends 10s. to 14s. (Rs. 5-7) a month on food, and a caste feast costs them about £6 (Rs. 60) the hundred guests. At their feasts they use large quantities of flesh and liquor. The men dress in short trousers, a waistcloth, a coat, a jacket, and a turban or headscarf. The women wear the Maratha robe and bodice, and like Maratha women, when at work, they tuck the end of the robe back between the feet. A family of five spends about £3 (Rs. 30) a year on clothes. Their women wear neck, nose, and ear ornaments, and glass bangles on their wrists. Most of them have spare clothes in store. They sometimes have sets of silver masks or taks in their houses which they worship without the help of any priest. Their priests are ordinary village Brahmans, who during the marriage stand at a distance and repeat the texts. They have a caste council; a few of them send their boys to school, and they are a steady class.

Mangs

Ma'ngs are returned as numbering 19,233 or 3.6 per cent of the Hindu population and as found all over the district. According to their tradition they are descended from Jambrishi, and their ancestors came into Pandharpur at the same time as the god Vithoba. They say that their high priest or chief Dakalvar, who lives in Karwar in North Kanara, knows their whole history and occasionally visits them. They are divided into Mangs proper, Mang Garudis, Pend Mangs, Holar Mangs, Mochi Mangs, and Dakalvars. Of these the first are considered the highest, and their leavings are eaten by Holars and Dakalvars. The Dakalvars say they are the highest branch of Mangs and that the others profess to despise them to punish the Dakalvars because they refused to touch the other Mangs. This story seems unlikely as Dakalvars eat the leavings of Mangs and Nade Mangs and no Mang will touch them. They are not allowed to drink water from a well or stream used by Mangs, but most take water from other Mangs. At the same time some sanctity or power attaches to the Dakalvars as no Mang will ever swear falsely by a Dakalvar. As a class Mangs are tall, some of them as much as six feet high, dark, and strongly made, and the white of their eyes is generally bloodshot. Most of the men wear the top-knot and the moustache, whiskers, and beard. Some men wear a tuft over each ear and no top-knot. They generally speak Marathi both at home and abroad. Sometimes among themselves at home they speak a language known as paroshi or out of use which is unintelligible to a Maratha stranger. Their Marathi accent and intonation are rough and coarse. They live by themselves in a quarter known as the Mangvada, separate from the Mhars, the hereditary rivals and enemies of their tribe. Their dwellings are generally thatched huts, though some own houses of the better sort with walls of earth and stone. The Mang Garudis or snake-charmers being a wandering class of jugglers have no fixed dwellings and live under a stretched canvas-like awning somewhat like a tent tied to pegs on the ground. They keep dogs and use donkeys and buffaloes as pack animals. The Mangs too keep donkeys, buffaloes, cows, oxen, sheep, and goats. Their staple food is jvari bread, vegetables, and pounded chillies, and they also eat the flesh of goats, sheep, dead cattle, and pork, but not of cows like the Mhars. On holidays they prepare dishes of gram cakes mixed with molasses. At caste feasts they drink kardai Carthamus tinctorius oil in large quantities, the feast costing 6s. to 8s. (Rs. 3-4) the hundred guests. They, have one-fourth share in every head of cattle that dies, while the Mhars have three-fourths and besides own the skin and horns. Their dress is the same as that of their neighbours the Mhars. They are passionate, revengeful and cruel, as the common expression Mang hridayi, or cruel hearted, shows. They are greatly feared as sorcerers, and are sturdy, fit for hard work, and trusty village servants. They are hardworking, unthrifty, dirty, and fond of pleasure and drink. All classes of Hindus from the highest to the lowest employ Mangs to punish an enemy by sending an evil spirit at him or else to overcome hostile charms, and, when some member of the family is possessed and does not speak, to find out and punish the witch that has possessed him. A mixture of chillies, part of a horse's leg or par near the knee, and hog's dung are burnt; and the face of the possessed person is held over the fumes. Then the spirit that is in the sick begins to speak through his mouth and tells who and what he is. Mangs make thin cord or chardte of ambada Hibiscus cannabinus or hemp and of kehtior Sweet Pandanus, ropes, date brooms, slings for hanging pots in, and also slings for throwing stones with, and bullock-yoke straps. They are carpenters, bricklayers, musicians, songsters, beggars, labourers, sellers of cowdung cakes grass and firewood, scavengers, and hangmen. Several of them are village watchmen and guides while others keep to their former trade of robbing and plundering. Like Chambhars and Mhars, Holars make shoes, slippers, whips, water-bags, saddles, harness, and horses' grain-bags. Dakalvars breed peacocks and are astrologers, going about with calendars and Purans. They beg only at the houses of Mangs, because they say they have a claim on Mangs who are their religious followers, and therefore they do not eat or drink with any other caste. Mangs rank lowest among Hindus and will take food from any caste except Bhangis. Mangs do not eat from the hands of twelve castes of which the only ones the Sholapur Mangs know are Ghadshis, Jingars, Mhars, and Buruds. They are not a religious people. Their chief deities are Ambabai, Jotiba, Khandoba, Mahadev, Mariamma, and Yallamma. Their fasts and feasts do not differ from those of Maratha cultivators. Unlike Mhars, who use the word Johar, that is Oh Warrior in saluting, Mangs say Pharman probably the Persian pharman or command to their castefellows; to others they say Maharaj, at the same time passing the right palm to their forehead. A woman is held impure for five weeks after childbirth, but after the twelfth day she is touched, though nothing is eaten from her hands. On the twelfth the goddess Satvai is worshipped and the child is put in a blanket-bag or jholi and named, the name being given by the village Brahman who is paid ⅜d, or ¼a. Female guests are asked and boiled gram or wheat is distributed among them. A month later new bangles are put round the mother's wrists. The boy's hair is cut at any time when he is between one and three years old and relations and friends are feasted. They marry their children very young, sometimes as babies, when the marriage ornaments or bashings are tied to the cradle instead of to the brow. Their betrothals do not differ from Mhar betrothals, the girl being presented with a bodice and robe worth 2s. to 10s. (Rs. 1-5), and clothes are exchanged between the two fathers. Mang marriages take place during Vaishakh and Jyeshth that is in April May and June, and on days when Brahmans perform their marriages. Daily for five days before the marriage the girl is rubbed with turmeric at her house, and the rest is sent with music to the boy. On the afternoon of the third day at both houses a sheep is offered to the family god and slain in the marriage hall. In the evening the boy's paternal uncle cousin or brother with music and kinspeople goes to the temple of Maruti carrying a hatchet in his raised hands, four men hold a cloth over his head, and cooked food or naivedya is carried with them. At the temple the Gurav or ministrant has ready as devaks or marriage guardians, mango jambhulSyzigium jambolanum, rui Calotropis gigantea, sondai properly saundad Prosopis spicegera, and umbar Ficus glomerata branches. The cooked food and a copper are laid before the guardians and they return with the devak and tie it to one of the posts in the marriage hall. After this the boy with kinspeople and music, goes either on a horse or a bullock to Maruti's shrine, when the girl's father meets him, and presents him with a waistcloth and turban, which he puts on and is led to the girl's and seated in the marriage hall. Then two baskets are taken, hides and ropes are placed in them, and the boy and girl are seated face to face and a curtain is held between them. [Some Manga instead of a hide place a grindstone in the girl's basket and a thick or thin rope in the boy's, instead of a cloth they hold up a quilt called jamnika, and instead of rice throw jvari.] The village Brahman, who acts as priest from a distance, repeats verses, and the guests who stand with rice grains in their hands throw them over the heads of the couple, and, when the verses are ended, they are husband and wife. Then they are made to stand side by side on the ground and are covered with the cloth which was held between them. Cotton thread is passed five times round them and divided into two pieces and one piece with a turmeric root is tied to the boy's right wrist and the other piece to the girl's left wrist. The couple are made to stand on an earthen altar orbahule and thrice change places. Their faces are rubbed with turmeric and the boy spends the night at the girl's sleeping with the other male guests in the marriage hall. The boy and girl play with betelnuts and beat each other's backs with twisted waistcloths. On the second and third the girl's parents feast the boy's and their own relations, and castefellows, and on the fourth the boy's father presents the girl with a bodice and robe and ties marriage ornaments to their brows. They are taken in procession to the village Maruti and thence to the boy's house. Next day the couple are sent round the villagers' houses, and the marriage ceremony is at an end. During the month of Shravan or August the girl's parents carry presents of a robe and bodice, wheat flour, molasses, and pulse to the boy's and fetch their daughter to their house. Mangs generally bury the dead. When any one dies fire is lit in the front part of the house and water heated over it in a new earthen jar, and the body is carried out of the house, bathed, and dressed in a waistcloth turban and coat; the body is then laid on a bier, redpowder and betel leaves are sprinkled over it, is raised on the shoulders of four men and carried to the burying ground, with a copper coin and some grains of rice tied to the hem of its garment. The chief mourner walks in front with an earthen firepot and his own turban under his armpit, and music, and the mourners follow. The musicians who belong to their own caste and play their pipes and drums are paid 3d. to 6d. (2-4 as.). On the way to the burying ground the bearers halt, but the firepot is not allowed to touch the ground lest it should become impure, and the copper coin in the shroud hem is thrown away. On reaching the burying ground a hole is dug and the body is lowered into the hole and laid on its back. The chief mourner dips the end of his turban in water, squeezes a little water into the dead month, and strikes his own mouth with his open hand that the gods may hear and open the gates of heaven, Svargi ghat vajte that is The bell of heaven rings. The grave is filled and the mourners bathe in a river or stream close by and return to the deceased's house each carrying some grass and nimb branches. At the house of mourning cow's urine is sprinkled on the spot where the dead breathed his last, and the grass and nimb leaves are thrown over the urine. The mourners return to their homes. On the third day the chief mourner with the four bearers and a kinsman or two go to the burial ground taking three Jvari cakes, cooked rice and curds, or only milk if the dead is a child. They leave one of the cakes at the rest-place and the other two on the grave. They bathe, return to the deceased's house, and are sprinkled with cow's urine. The four corpse bearers sit in a line, and their shoulders are touched with nimb leaves dipped in sweet oil. They are then fed on jvari, molasses, oil, andsanja or a mixture of wheat flour and sugar and clarified butter. The chief mourner is held impure for twelve days during which he is not touched. At the end of the twelve days a caste dinner is given when jvari bread and pulse are served. At night one of their own sadhus or ascetics is called. He pours water from an earthen jar on the spot where the dead breathed his last, and the night is spent in reading sacred books or singing hymns in praise of the gods. They allow widow marriage and polygamy. They have a headman called mhetrya and settle social disputes at meetings of the leading members of the caste. They levy fines of 2s. 6d. to 10s. (Rs. 1¼ -5) and spend the amount on a caste feast. Till the feast is given the offender is not allowed back into caste. They do not send their boys to school and are poor.

Mhars

Mha'rs are returned as numbering about 44,000 or 8.16 per cent of the Hindu population and as found over the whole district. They are divided into Advans, Bavans, Godvans, Kadvans or bastards, Soms, and Tilvans, who except the Kadvans all eat together and intermarry. Of these divisions the Soms, or Somvanshis, are the most numerous. Their surnames are Jadhav, Jugle, More, Shelar, and Sarvgod. They are generally tall, strong, muscular, and dark, with regular features and low unintelligent foreheads. The men shave the head except the top-knot; some wear whiskers, all wear the moustache, and a few wear beards. The women wear their hair either in a braid, or in a knot, or loose. Their home speech is Marathi. They live outside of the village in untidy and ill-cared for houses of mud and stones with thatched or in rare cases flat mud roofs. Most of them live in huts with wattle and daub walls. Except a few of metal, their cooking and water vessels are made of earth. The well-to-do rear cattle, sheep, and fowls. Their daily food is millet bread, split pulse, and pounded chillies. They eat the leavings of other people, and when cattle and sheep die they feast on their carcasses. They do not eat pork. Mhars scorn Mangs for eating the pig, and Mangs scorn Mhars for eating the cow. They drink liquor and smoke tobacco and hemp flower. Their holiday dinners include rice cakes and a liquid preparation of molasses. Within the last ten years several Mhars have become Yaishnavs and given up flesh and liquor. A man's indoor dress is a loincloth, and, in rare cases, a jacket; his outdoor dress is the same, with, in addition, a white turban or a cap, and a blanket. Both indoors and out of doors women wear the ordinary Maratha robe, generally red or black, and a bodice, and children of both sexes under seven or eight and sometimes up to ten, go naked. Except that it is somewhat richer, the Mhar's ceremonial dress is the same as their outdoor dress. Their clothes are country-made and are bought in the local markets. Both men and women spend 8s. to 10s. a year on clothes. The women wear glass and lac bangles, brass earrings, a necklace of black glass beads, a black silk neck-cord or nada, and silver finger and toe rings. The men formerly wore a black thread round their neck, but many of them have of late given up the practice. They carry in their hands a thick staff about four feet long and with one end adorned with bells. They are fairly hardworking and hospitable to their castefellows, but they are dishonest, intemperate, gluttonous, hot-tempered, mischievous when they have a quarrel, and occasionally given to petty gang robberies. Mhatjaticha or Mhar-natured is a proverbial term for a cruel man. They are village servants and are authorities in boundary matters; they carry Government treasure, escort travellers, call landholders to pay the land assessment at the village office, and remove dead animals. Most of them enjoy a small Government payment partly in cash and partly in land, and they occasionally receive presents of grain from the village landholders. They do watchman's work by turns, and the man in office is called veskar that is gatekeeper. He goes about begging food from the villagers, skins dead cattle, and sells the skins and horns. Besides as watchman and boundary referee he is useful to the villagers by taking wood and cowdung cakes to the burning ground or by digging the grave when a villager dies, and carrying the news of his death to his kinspeople in neighbouring villages. Some are husbandmen, labourers, street and yard sweepers, and others gather wood and cowdung and cut grass. The Mhar prepares the threshing floor or khale at harvest time and watches the corn day and night before it is stored in a grain pit or pev. He formerly received a sixteenth to a twentieth of the produce of the land as the grain allowance or balute, the corn that falls on the ground at the foot of every stalk, and a bodice and robe or a headscarf at every marriage at a landholder's house. They are a poverty-stricken class, barely able to maintain themselves, and often living on the refuse of food thrown into the streets. They hold a low position among Hindus and are both hated and feared. Except in Pandharpur, their touch, even the touch of their shadow, is thought to defile. In Pandharpur Mhars mix freely with other castes, Brahmans and Mhars bringing their supplies from the same shop and drinking water from the same pool. Formerly an earthen pot was hung from their necks to hold their spittle, they were made to drag thorns to wipe out their footsteps, and when a Brahman came near had to lie far off on their faces lest their shadows might fall on him. Even now, a Mhar is not allowed to talk loudly in the street while a well-to-do Brahman or his wife is dining in one of the houses. Mhars are Shaivs and Vaishnavs and worshippers of goddesses. Most of them are Vaishnavs and worship Bhavani of Tuljapur, Chokhoba, Jnyanoba of Alandi, Khandoba of Jejuri, and Vithoba. They also worship the usual Hindu gods and goddesses and Musalman saints especially the ancestral Cobra or Nagoba, the small-pox goddess Satvai, and the cholera goddess Mariai whose shrines are found in all Mhar quarters. They go on pilgrimage to most of the places mentioned above as well as to the shrine of Shambhu Mahadev in Satara.

Their religious teachers are Mhar gurus and sadhus or gosavis. They have also Mhar vachaks or readers, who read and explain their sacred books, the Bhaktivijay, Dasbodh, Jnyaneshvari, Harivijay, Ramvijay, Santlila, and the poems of Jyanoba, Tukoba, and others. The readers also preach, and repeat marriage verses when a Brahman is not available. The gurus, sadhus, vachaksand Mhar gosavis all belong to the Mhar caste and some of them are very fluent preachers and expounders of the Purans. Any one of these lecturers who maintains himself by begging may become a guru or teacher. Every Mhar both among men and among women has a guru;if they have no guru they are not allowed to dine in the same line with the sadhus. A child is first brought to be taught by its guru when it is about a year old. The rite is calledkanshravni or ear-whispering and more commonly kanphukne or ear-blowing. About seven or eight at night the parents take the child in their arms and go to the teacher's house, currying frankincense, camphor, red and scented powders, flowers, betelnut and leaves, a cocoanut, dry dates, and sugar. In the teacher's house a room is cowdunged and a square is traced with white quartz powder. At each corner of the square a lighted lamp is set, and, in the middle, on a wooden plank or on a low wooden stool, is a metal pot or ghat filled with cold water. Another board or stool is set facing the square and the teacher sits on it cross-legged. He sets flowers, sandal paste, and rice on the waterpot and takes the child in his lap resting its head on his right knee. He shrouds himself and the child in a blanket or a waistcloth, matters the sacred Terse into the child's right ear, pulls off the blanket, and hands the child to its parents. The priest is presented with. 3d. to 2s. (Re. ⅛ -1), and, if they are well-to-do, the parents give him a waistcloth, one or two metal water vessels and a plate. A feast is given to the teacher and a few near relations, or if the parents cannot afford a feast, sugar is handed round. After the dinner the parents retire with the child. When cholera rages in a village the people raise a subscription and hand the money to the headman. The headman brings a robe and a bodice, some rice and flour, a he-buffalo or a sheep, and flowers, camphor, frankincense, redpowder, and betelnut and leaves. He takes three carts, fills one with cooked rice, a second with cakes, and in the third places the other articles of worship, and, leading the fee-buffalo, takes the carts through the village accompanied by music and a band of the villagers. The carts then go to the Mhars' quarters outside of the village, where is the shrine of Mariai the cholera goddess. The headman and the other villagers stand at a distance, while a Mhar bathes the goddess, dresses her in the robe and bodice, fills her lap with rice, betelnuts, dry dates, and a cocoanut, waves burning frankincense and camphor before her, and with joined hands begs her to be kind. All the villagers lift their joined hands to their heads, and ask the goddess to be kind, and retire leaving the Mhars and Mangs. The buffalo is led in front of the goddess and a Mhar chops off its head with a sword or a hatchet, and touches the goddess' lap with a finger dipped in its blood. The cart-loads of food and meat are shown to the goddess and are distributed among such of the villagers as do no object to eat them. This concludes the sacrifice. They say that the goddess truly partakes of the sacrifice, as the food and meat become insipid and tasteless. The Mhar's priests are village Brahmans who do not object to act as priests at their marriages and other ceremonies. In their daily worship Mhars do not require the help of Brahmans. The office of religious teacher or guru is hereditary. They believe in sorcery witchcraft and soothsaying. They have many spirit-scarers or exorcists among them some of whom are Gosavis who have been devoted to the service of the gods since they were born, and the rest are potras or devotees of Lakshmi, who cover their brows with redpowder and carry a whip with which they lash their bodies while they beg singing and dancing. They fast on Mondays and on the eleventh of each half of every lunar month. Recent changes in religious views are confined to the Varkaripanth or timekeeping sect After the birth of a child the mother is held impure for twelve days, during which she keeps aloof from every one except the midwife. On the third day a ceremony called tirvi is performed, when five little unmarried girls are feasted on millet or karri made into lamps and eaten with a mixture of milk and molasses, or sugar, or with cards and buttermilk. On the fifth or panchvi day five stone pebbles are laid in a line in the house and worshipped by the midwife and millet is offered. On the sixth or satvi day the hole made for the bathing water in the mother's room is filled, levelled, cowdunged, and sprinkled with turmeric and redpowder and flowers, and wheat cakes are laid before it. On the twelfth day the baravi or twelfth day ceremony is performed, when the whole house is cowdunged and seven pebbles are laid outside of the house, worshipped by the mother, and presented with wheat bread. Five married women are feasted. Between the thirteenth and any time within about two months, the boy's father goes to the village astrologer, gives him the time of the child's birth, and asks him whether the moment of birth was a lucky moment. The Brahman tells him to offer a cocoanut to the village Maruti or some other village god, and to pour a copper's worth of oil on him. The father asks for a name for the child, the astrologer looks up his almanac and tells him. The father goes home and tells the women of the house what name the priest has given. In the evening married women are called, a spot is cowdunged, a drawing is traced with white quartz powder, and the cradle is set in the tracing. The mother brings the child and lays it in the cradle, in a loud voice calls it by the name chosen by the astrologer, and putting her mouth to the child's right ear says kur-r-r. If the astrologer's name is not to the mother's liking she calls the child by another name, and the women sing songs. A handful of millet, a little sugar, and betel are served and the guests retire. When the child is a year old, if it is a boy, the hair-cutting or javal is performed. The child is taken to the shrine of the goddess Satvai, and his hair is either clipped or shaved by one of the family who leaves a few hairs on the crown. The goddess is worshipped, a few hairs are laid before her, and she is offered wheat bread and cooked rice. There is no other ceremony till marriage. Mhars marry their girls sometimes when they are infants and always before they come of age, and their boys sometimes before they are twelve and seldom after they are twenty. They have no rules forcing them to marry their girls before they come of age. Among them the magni or asking the girl's parents to give their daughter in marriage is the same as among Marathas. About a week before, the village Brahman is asked whether there is anything in the names of the boy and girl to prevent their marrying. He consults his almanac and says there is no objection. He is then asked to fix a lucky moment for the marriage and for the turmeric rubbing. He again consults his almanac and tells them the days and gives them a few grains of rice which he blesses in the name of Ganpati. Each of the fathers gives the Brahman a copper for his trouble. For four days before the marriage the parents both of the boy and of the girl rub them with turmeric powder, and branches of five trees or panchpalvis are worshipped as the marriage guardian or devak. On the marriage day the boy, with kinspeople friends and music, goes to the girl's sometimes on horseback and generally on an ox. On reaching the girl's the girl's brother or some other near kinsman leads the boy into the house and seats him on a blanket. The girl is brought by her sister or some other kinswoman and seated on the blanket beside the boy. The guests of both houses feast at the girl's where a sheep has been killed in the morning. The boy is presented with a turban, a waist-cloth, a shouldercloth, and a pair of shoes. He dresses in the new clothes and takes his stand on a wooden stool near the blanket. The girl stands on another stool facing hen, and each of them holds a roll of betelnut and leaves in both hands. A cloth is held between them, the boy and girl stretch out the tips of their fingers till they touch on either side of the cloth or below the cloth and the village priest from some distance, or if not one of their own holy men repeats marriage verses. When the last verse is over the guests throw over the couple's head rice mixed with the rice which the Brahman astrologer gave the fathers at the time of settling the marriage day. The cloth is pulled on one side and five persons hold it over the pair's heads. To the hems of the pair's garments are tied rice, turmeric roots, and betelnut, and they are seated on the altar or bahule. Cotton thread is passed five times round the fingers of the five cloth holders, and again four times, and each of the two windings is made into a string about a cubit long, and the string of five turns, with a turmeric root and a betelnut tied to it, is wound round the boy's right wrist and the string of four turns round the girl's right wrist. Then a married man repeats his wife's name and unties the knot that fastens together the hems of the boy's and girl's garments. Kinswomen and the bride's and bridegroom's maids or karavlis wave lighted lamps round the couple's faces. Each of the fathers pays the Brahman 3d. (2 as.) and gives him a cocoanut, sugar, and betel. For four days, including the marriage day, the boy stays at the girl's and feasts are held. On the evening of the fifth comes the sada or robe ceremony when the boy's father presents the girl with a robe and bodice, a necklace of black glass beads with a gold bead in the centre, glass bangles, and silver toe-rings. The boy and girl are seated on the laps of their maternal uncles and bite the ends off betel leaf rolls, and a piece of cocoa kernel is hung between them from a black thread. At night a procession is formed and the boy and girl are seated on an ox and paraded through the village with kins-people, music, and dancing. The marriage is over and the guests go home. Either on Sankrant Day the twelfth of January, or on Nagpanchmi in July-August comes the vavsa or home-taking, when the boy with his parents and kinspeople goes to the girl's, taking a robe and bodice, a measure of wheat flour, pulse, and clarified butter and molasses. At the girl's they are feasted, and, after the feast, take the girl back with them to the boy's house.

When a Mhar girl comes of age she sits five days by herself. At the end of the fifth day she is presented with a white robe and bodice and the caste is feasted. They allow and practise widow marriage and polygamy. Mhars generally bury the dead. After death the relations weep over the dead, lay his body on the threshold of the house, and throw over him warn water heated in a new earthen jar. The body is shrouded in a new cloth, laid on the bier, and sprinkled with redpowder and betel leaves, and grains of rice are tied to one of the hems of the cloth. The body is carried to burial on the shoulders of four near kinsmen who as they pass gay Ram Ram in a low voice. The chief mourner walks in front with fire in the new earthen jar and music if he has the means. The mourners follow. On the way to the grave the party halts, the rice from the hem of the deceased's robe is laid on the ground, and five pebbles are set on the rice. When they reach the burial ground, a pit five feet deep is dug, and the body is stripped of all its clothing, even the loincloth, according to the saying, Naked hast thou come and naked shalt thou go. It is lowered into the grave and laid on its back. The chief mourner scatters a handful of earth on the body, the rest also scatter earth, and the grave is filled. The chief mourner fills the firepot with water, sets it on his shoulder, and goes thrice round the grave crying aloud and striking his open mouth with the palm of his right hand. At the end of the third turn he pours water from the jar on the grave and dashes the jar to pieces on the ground. All bathe in running water, and go to the mourner's house each carrying a nimb branch. At the house an earthen pot of cow's urine is set on the spot where the dead breathed his last, the mourners dip the nimbbranches into the urine, sprinkle it over their heads and bodies, and go to their homes. On the third day a few of the deceased's kinsmen go to the burial ground, the chief mourner carrying in his hands a winnowing fan with two pieces of cocoa-kernel and some molasses in each piece. At the rest-place, where the bearers halted, they lay a piece of cocoa-kernel with molasses on it under the five stones. The other piece is laid on the heaped grave. They beat the grave down to the level of the rest of the ground, bathe, and go to the chief mourner's house. The four bearers are seated in a line on the bare ground in the front room of the house. Each holds a nimb branch under his arm, the chief mourner drops a little molasses into his mouth, and they go to their homes. On the seventh day a bread and vegetable caste feast is given. Like Marathas Mhars keep the death-day, when crows are fed with rice and a dish of molasses. They settle social disputes either by a council or panchayat composed of the foremost members of the caste, under the hereditary headman called patil, or by a caste-meeting. Caste decisions are enforced by forbidding the caste people to smoke or drink water with the offender, or by exacting a fine of 6d. to 10s. (Rs.4-5) which is spent on drink. Mhars some times send their boys to school, but they never take to new pursuits. They are a poor people.