Ghasi, Chota Nagpur

Ghasi

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Origin

A Dravidian fishing and caste of Chota Nagpur and "Central India, who attend as weddings aud festivals and also

perform menial offices of all kinds. Ghasi women act as mid wives and nurses, and I have come across a case of a Brahman girl being nicknamed Ghasimani in. her infancy and made over to a Ghasi woman to bring up in order to aved the malevolent influences supposed to have caused the early death of previous children of the same mother.

Internal structure

The Ghasis of Chota Nagpm are dividcd into three sub• castes¬Sonaati, Simarloka, and Hari. They have only one section (Kasiar), probably a corrup-tion of Kasyapa. Ghasis marry their daughters in infancy when they can afford to do so, but adult-mflrriage is by no means uncommon. Their marriage ceremony is a debased form of that in ordinary use among orthodox Hindus. Polygamy is permitted without any limit being imposed on the number of wives. Widow-marriage and divorce are freely practised, and the women of the caste are credited with living a very loose life.

==Social status. The caste ranks socially with Doms and Musahars. They eat beef and pork, and are greatly addicted to drink. Their origin is obscure. Colonel Dalton regards them as Aryan helots, and says:¬ " But far viler than the weavers are the exlraordinary tribe called Ghasis, foul parasites of the Central Indian hill tribe, and submit¬ting to be degraded even by them. If the Chandals of the Purans, though descended from the union of a Brahmani and a Sudra, are the 'lowest of the low,' the Ghasis are Chandals, and the people who further south are called Pariahs are no doubt of the same distinguished lineage. H, as I surmise, they were Aryan helots, their offices in the household or communities must have been of the lowest and most degrading kinds. It is to be observed that the institution of caste necessitated the organization of a class to whom such offices could be assigned, and when formed, stringent measures would be requisite to keep the servitors in their position. We might thence expect that they would avail themselves of every opportunity to escape, and no safer asylums could be found than the retreats ot the forest tribes. Wherever there are Kols there are Ghasis, and though evidently of an entirely different origin, they have been so long assooiated that they are a recognised class in the Kol tradition of creation, which appropriately assigns to them a thriftless career, and describes them as living on the leavings or charity of the more industrious members of society. There are not fewer than 50,000 Ghasis in the Kol countries. Their favourite employment is no doubt that of musicians. No ceremony can take place or great man move without the accompanimsnt of their discordant instruments -drums, kettle-drums, and huge horns-to proclaim the event in a manner most horrifying to civilised ears."

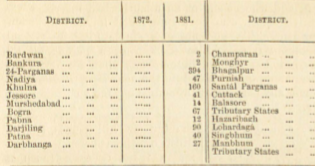

The Simarloka sub-caste have a curiou aversion for K6yasths, which they account for by the story that once upon a time some Ghlisi musicians, who were escorting the marriage procession of a Kayasth bridegroom to the house of his betrothed, were tempted by the valuable ornaments which he wore to murder him and cast his body into a well. The youth besought them to let him write a letter to his relatives informing them that he was dying and bidding them perform his funeral obsequies. 'l'his the Ghasis agreed to, after making him swear that he would not disclose the manner of his death. The Kayastb, however, did nnt think the oath binding, and on the letter being delivered the Gh6sis were straightway given up to justice. For tills renson, say the Simarloks, trust not a Kayosth, for he is faithlcss even in the hour of death. The following statement shows the number and distribution of GMsis in 1872 and 1881 :¬