Indo-European cuisine

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Anglo-Indian cuisine

Jenny Mallin’s cookbook

The Times of India, Sep 14 2015

Joeanna Rebello 500 recipes with a bite of history

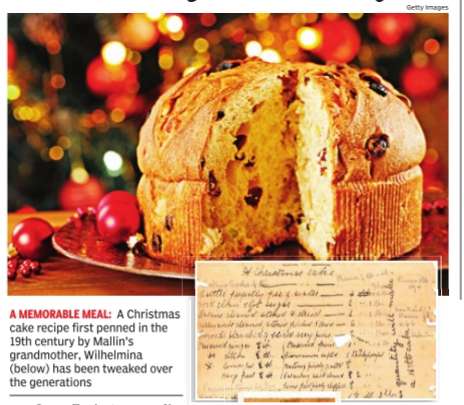

An Anglo-Indian writer traces her roots through a cookbook handed down four generations of grandmothers. Every competitive cook guards her recipes, but few would go so far as to deposit them in a bank. Jenny Mallin's inheritance contains over 500 recipes dating back to 1844.Based on this legacy , the former BBC TV producer has now self-published a book called A Grandmother's Legacy: A Memoir of Five Generations Who Lived Through The Days of The Raj.

Jenny's Anglo-Indian parents relocated to England in 1953, carrying with them the old cookbook, its saucestained pages containing well-loved family recipes such as Mahratta Curry, Yorkshire Puddings, Christmas Cakes, Ginger Wine, Quoorma (Kurma), and Almode (a lamb stew made with the middle neck of lamb, braised in chillies, garlic, cloves, cinnamon, peppercorns, cardamom and bay leaves).

A beloved recipe like Christmas cake, for example, adapted with time as innovation brought convenience to the counter. “I have at least seven versions of the recipe (each written by a different grandmother or perhaps the cook) and within each recipe, you can see evidence of how another person has crossed out an ingredient and included a new one,“ says Jenny . For instance, earlier versions included plums, which were “cleaned, stoned and dried out in the sun“, and then a grandmother replaced them with Sun Maid Raisins and prunes. Another grandmother has decided to follow the same recipe, but in stead of 4lbs of butter has replaced it with 2lbs of ghee (clarified butter).

“Once the railways started, my grandmothers travelled right across India (my grandfathers were all Permanent Way Inspectors and were enti tled to travel with their family in their own railway carriage). The grandmothers' recipes became a `fusion' of local ingredients with their British heritage, so a recipe for scrambled eggs would be enhanced by the addition of green chillies, onions, tomatoes and ventheum (fenugreek) leaves and my great great grandmother Ophelia penned that recipe in the book as `Matheekie Barge' (methi being another word for ventheum and I suspect `barge' referred to bhaji).,“ rec o u n t s Je n ny.One grandmother has even annotated costs in lieu of measures, specifying one paise worth of chillies, for example.

The recipes, like old family albums, were a peephole into her family's lifestyle, their measurements indicative of large gatherings and large appetites.“What their recipes reveal is their genuine love of good hospitality where doors are thrown open to family , friends and neighbours. It may be for a special birthday event, or an elegant tea party complete with cut sandwiches made from Grandma's Brown Bread recipe to Afternoon Teacakes, Hot Scones, Lemon Cake, and of course Christmas Cake,“ observes Jenny.

The grand old cookbook was invariably bequeathed to the eldest daughter, but it was later passed on to whichever daughter loved to cook. And so Jenny's mother, Cynthia came to possess it and passed it on to her youngest child.

A backgrounder

As of 2024

Asha Prakash, Oct 14, 2024: The Times of India

Indo-European cuisine wasn’t just fusion food invented for restaurant menus such as Indian-Chinese, but an actual cuisine which was a staple for the British, French, Portuguese and Dutch who lived in the country. It evolved over a couple of centuries, but with no one to carry them forward, many dishes have been lost to time and migrations. Now, a few individuals and families are trying to preserve them.

VIVA LA VADAVOUM

Puducherry’s cuisine is more than Franco-Tamil, it’s a distinct blend of Dutch, Portuguese and Vietnamese influences. Few kept it alive once the French left Puducherry, but one family is making sure the world doesn’t forget them. Come Sundays and the table at Motchamary Pushpam’s home in Puducherry is laden with salad creole (a French dish made with beetroot, vinegar and olive oil), fish assad (a Portuguese dish), venna puttu (a popular breakfast item in Vietnam, cooked with coconut milk, jaggery and brown sugar) and mutton sambar. “We call this venture the ‘Table of Hope’ as we are on a mission to preserve these dishes,” says Anita de Canaga, chef Pushpa’s daughter who grew up in France and returned to Puducherry in 2008. . At the Table of Hope, however, a guest will never know what’s on the menu until he/ she gets. “We call it ‘Chez Pushpa’ (Pushpa’s home). My mother buys local produce fresh from the market and prepares what she feels like on the day. Guests are invited to a cooking class beforehand.” The French couldn’t han- dle spices and so a special sundried seasoning of mild spices was made for them, says Pushpa, adding that they prepare this vadavoum from scratch and use it for chutneys duck and pork.

What started out as an informal lunch soon caught up and chefs started attending the lunches and masterclasses, including Radisson Blu, which now conducts Franco-Tamil food festivals based on chef Pushpa’s recipes.

WHAT ARE YOU EATING, DORAI?

In times when food relied on local ingredients, each region developed its own variations of Indo-European cuisine, says chef and food historian Shri Bala.

“The British would escape to the hill stations of Ooty and Kodaikanal in summer, taking along butlers and cooks. Lesser lords stayed in Yercaud,” she says. The root vegetables, abundant in the region, paired well with mutton, giving rise to dishes such as the now-obscure Yercaud dorai (lord) curry, made with turnip and khol khol. “It was cooked with tender mutton and drumstick, likely for its aphrodisiac qualities,” she says. Without a written recipe, Bala recreates it with bone stock and fat at her restaurant in Chennai, one of the only places it is served.

“Dorai curry is among the lessknown hill station dishes. Another more popular dish is the railway mutton curry, cooked with tender minced meat. It was called ‘first-class railway mutton curry’ as it was meant for the British, the only ones who travelled first class.” Legend has it that a drunken lord once found it too spicy and added coconut milk. “Even today, it has coconut milk in it besides baby potatoes and butter.” The cuisine also includes devil’s chutney, trifle pudding, caramel custard and the iconic mulligatawny soup, still occasionally served in clubs with Anglo-Indian cooks.

GRANDMA MAUD AND MEAT DING-DING

When not written down, says Bridget White Kumar, many recipes die with the generation which cooked them with intuition and memory. “Colonial Anglo-Indian cuisine is slowly going extinct, which is why I publish cookery books featuring dishes prepared exclusively by the older generation.”

Among the dishes in her book are childhood favourites such as country captain chicken. “In the 1950s, our family gathered every Sunday at my grandparents’ home in Robertsonpet at Kolar Gold Fields in Karnataka,” she says. “We’d watch grandma Maud White cook home-reared fowl over firewood for two hours. It was rich and delicious and served with rice My mouth still waters thinking about it. The dish slowly disappeared with the introduction of broiler hens in the market.”

In the past, game was plentiful, and meat was preserved by soaking it in spices and vinegar before sun-drying, which was how the meat ding-ding originated. “But with fresh meat now readily available, there’s no longer a need to dry and preserve it,” says Bridget.

Kedgeree, an Anglicised version of kichidi, was prepared with rice, lentils, raisins, fried fish flakes and hard-boiled eggs. “Fish — steamed or fried — was a breakfast staple for the British, so cooks mixed it with local dishes. Minced meat was later added as a variation. Today, fish pulao has replaced kedgeree in Anglo-Indian homes,” she says.

The Presidency cities of Bombay and Madras and many small towns had their own versions of the cuisine, adapting regional flavours, ingredients and local produce, says Bridget. “The Anglo-Indians in the South, particularly in Chennai, preferred their dishes watery, using sauces, tomatoes and tamarind.” The unusual blend of tastes is what makes the cuisine a gourmet’s delight, says Bridget.