Karauli State, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Karauli State

Physical aspects

State in the east of Rajputana, lying between 26 degree 3' and 26 degree 49' N. and 76° 34" and 77 degree24' E., with an area of 1,242 square miles. It is bounded on the north by Bharatpur; on the north-west and west by Jaipur; on the south and south-east by Gwalior ; and on the east by Dholpur. Hills and broken ground characterize almost the whole territory, which lies within a tract locally termed the Dang, a name given Physical to the rugged region immediately above the narrow valley of the Chambal. The principal hills are on the northern border, where several ranges run along, or parallel to, the frontier line, forming somewhat formidable barriers. There is little beauty in these hills ; but the military advantages they present caused the selection of one of their eminences, Tahangarh, 1,309 feet above the sea, as the seat of Jadon rule in early times.

Along the valley of the Chambal an

irregular and lofty wall of rock separates the lands on the river bank

from the uplands, of which the southern part of the State consists.

From the summits of the passes the view is often picturesque, the

rocks standing out in striking contrast to the comparatively rich and

undulating plain below. The highest peaks in the south are Bhairon

and Utgir, respectively 1,565 and 1,479 feet above the sea. Farther

to the north the country falls, the alluvial deposit is deeper, level

ground becomes more frequent, and hills stand out more markedly,

while in the neighbourhood of the capital the low ground is cut into

a labyrinth of ravines.

The river Chambal forms the southern boundary, separating the State from Gwalior. Sometimes deep and slow, sometimes too rocky and rapid to admit of the safe passage of a boat, it receives during the rains numerous contributions to its volume, but no considerable perennial stream flows into it within the boundaries of the State. The Banas and Morel rivers belong more properly to Jaipur than, to Karauli ; for the former merely marks for some 4 miles the boundary between these States, while the latter, just before it joins the Banas, is for only 6 miles a river of Karauli and for another 3 miles flows along its border. The Panchnad, so called from its being formed of five streams, all of which rise in Karauli and unite 2 miles north of the capital, usually contains water in the hot months, though often only a few inches in depth. It winds away to the north and eventually joins the Gambhir in Jaipur territory.

In the western portion of the State a narrow strip of quartzites belonging to the Delhi system is exposed along the Jaipur border, while Upper Vindhyan sandstones are faulted down against the quartz- ites to the south-east, and form a horizontal plateau extending to the Chamal river. To the north-west of the fault, some outliers of Lower Vindhyan rocks occur, consisting of limestone, siliceous hreccias, and sandstone, which form two long synclinals extending south-west as far as Naraoli.

In addition to the usual small game, tigers, leopards, bears, iri/gai, sdmdar, and other deer are fairly numerous, especially in the wooded glens near the Chambal in the south-west.

History

The climate is on the whole salubrious. The rainfall at the capital averages 29 inches a year, and is generally somewhat heavier in the north-east at Machilpur and the south-east at Mandrael. Within the last twenty years the year of heaviest rainfall has been 1887 (45-i inches), while in 1896 only a little over 17 inches fell.

The Maharaja of Karauli is the head of the Jadon clan of Rajputs, who claim descent from Krishna. The Jaddns, who have nearly always remained in or near the country of Braj round Muttra, are said to have at one time held half of Alwar and the whole of Bharatpur, Karauli, and Dholpur, besides the British Districts of Gurgaon and Muttra, the greater part of Agra west of the Jumna, and portions of Gwalior lying along the Chambal. In the eleventh century Bijai Pal, said to have been eighty-eighth in descent from Krishna, established himself in Bayana, now belonging to Bharatpur, and built the fort overlooking that town. His eldest son, Tahan Pal, built the well-known fort of Tahangarh, still in Karauli territory, about 1058, and shortly afterwards possessed himself of almost all the country now comprising the Karauli State, as well as a good deal of land to the east as far as Dholpur.

In n 96, in the time

of Kunwar Pal, Muhammad Ghorl and his general, Kutb-ud-dln,

captured first Bayana and then Tahangarh ; and on the whole of the

Jadon territory falling into the hands of the invaders, Kunwar Pal fled

to a village in the Rewah State. One of his descendants, Arjun Pal,

determined to recover the territory of his ancestors, and about 1327

he started by capturing the fort of Mandrael, and gradually took

possession of most of the country formerly held by Tahan Pal. In

1318 lie founded the present capital, Karauli town.

About a hundred years later Mahmud I of Malwa is said to have conquered the country, and to have entrusted the government to his son, Fidwi Khan. In the reign of Akbar (1 556-1 605) the State became incorporated in the Delhi empire, and Gopal Das, probably the most famous of the chiefs of Karauli, appears to have been in considerable favour with the emperor. He is mentioned as a com- mander of 2,000, and is said to have laid the foundations of the Agra fort at Akbar's request. On the decline of the Mughal power the State was so far subjugated by the Marathas that they exacted from it a tribute of Rs. 25,000, which, after a time, was commuted for a grant of Machilpur and its dependencies. By the treaty of November 9, 1817, with the East India Company, Karauli was relieved of the exactions of the Marathas and taken under British protection ; no tribute was levied, but the Maharaja was to furnish troops according to his means on the requisition of the British Government. In 1825, when the Burmese War was proceeding, and Bharatpur was preparing for resistance under the usurpation of Durjan Sal, Karauli undoubtedly sent troops to the aid of the latter ; but on the fall of that fortress in 1826 the Maharaja made humble professions of submission, and it was deemed unnecessary to take serious notice of his conduct.

The next event of any importance was the celebrated Karauli adoption case. Narsingh Pal, a minor, became chief in 1850, and died in 1852, having adopted a day before his death a distant kinsman, named Bharat Pal. It was first proposed to enforce the doctrine of 1 lapse,' but finally the adoption of Bharat Pal was recognized. In the meantime a strong party had been formed in favour of Madan Pal, a nearer relative, whose claim was supported by the opinions of several chiefs in Rajputana. An inquiry was ordered ; and it was ascertained that the adoption of Bharat Pal was informal, by reason of the minority of Narsingh Pal and the omission of certain necessary ceremonies. As Madan Pal was nearer of kin than Bharat Pal and was accepted by the Ranis, by nine of the most influential Thakurs, and by the general feeling of the country, he was recognized as chief in 1854. During the Mutiny of 1857 he evinced a loyal spirit and sent a body of troops against the Kotah mutineers ; and for these services he was created a G.C.S.I., a debt of 1-2 lakhs due by him to the British Government was remitted, a dress of honour conferred, and the salute of the Maharajas of Karauli was permanently increased from 15 to 17 guns. The usual sanad guaranteeing the privilege of adoption to the rulers of this State was granted in 1862, and it is remarkable that the last seven chiefs have all succeeded by adoption.

Maharaja Bhanwar Pal, the present ruler, was born in 1864, was installed in 1886, obtained full powers in 1889, and, after receiving a K.C.I.E. in 1894, was made a G.C.I.E. in 1897. The nobles are all Jadon Rajputs connected with the ruling house, and, though for the most part illiterate, are a powerful body in the State, and until quite recently frequently defied the authority of the Darbar. The chief among them are Hadoti, Amargarh, Inaiti, Raontra, and BarthQn, and they are called Thekanaddrs. The Rao of Hadoti is looked upon as the heir to the Karauli gaddi, when the ruling chief is without sons.

The only places of archaeological interest are Tahangarh, already mentioned, and Bahadurpur, 8 miles south of the capital ; both are now deserted and in ruins.

Population

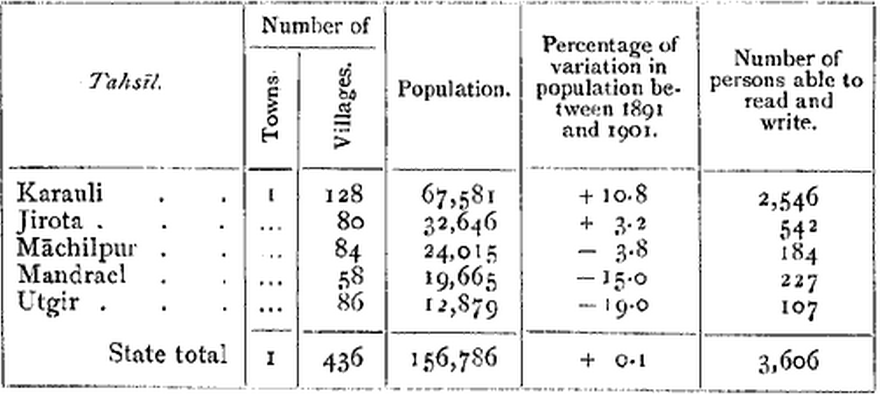

The number of towns and villages in the State is 437, and the population at each of the three enumerations was : (1881) 148,670, (1891) 156,587, and (1901) 156,786. The smallness Population. of the increase during the last decade is ascribed to famines in 1897 and 1899. The territory is divided into five tahsils: namely, Karauli (or Sadr), Jirota, Machilpur, Mandrael, and Utgir, the head-quarters of each being at the place from which it is named, except in the case of jirota and Utgir, the head-quarters of which are at Sapotra and Karanpur respectively. The only town in the State is the capital, a municipality.

The following table gives the chief statistics of population in 1901 :—

Nearly 94 per cent, of the total are Hindus, the worship of Vishnu under the name of Krishna being the prevalent form of religion, and more than 5 per cent, are Muhammadans. The languages mainly spoken are dialects of Western Hindi, including Dangi and Dangbhang.

The principal tribe is the Minas, who number 32,000, or more than 20 per cent, of the population, and are the leading agriculturists of the country; next come the Chamars (23,000), who, besides working in leather, assist in agriculture. Brahmans number 20,000, and are mostly petty traders, village money-lenders, and cultivators ; while the Gujars (16,000), formerly noted cattle-lifters, are now very fair agriculturists.

Agriculture

Agricultural conditions vary in different parts of the State. In the highlands of the Dang the soil is clayey, and the slopes of the hills are embanked into successive steps or terraces, only a few yards broad ; here rice is grown abundantly, and after it has been reaped barley or gram is sometimes sown. The fields are irrigated from tanks excavated on the tops of the hills. The lowlands of this tract are surrounded by hills on two or three sides and are called antrl. The soil is of two kinds : the first is composed of earth and sand washed down the hill-sides by the rain- fall, and is of very fair quality, while the second is hard and stony and is called kanknll. The crops grown here are mostly bajra and moth, though the better of these two soils produces fair spring crops where irrigation from wells is possible. On the banks of the Chambal the soil is generally rich, and the bed of the river is cultivated to the water's edge in the cold season. The principal crops here are wheat, gram, and barley. Elsewhere, outside the Dang, the soil is for the most part light and sandy, but in places is associated with marl. Excellent crops of bajra, moth, and jowar are produced in the autumn ; and by means of irrigation, mostly from wells, good crops of wheat, barley, and gram in the spring.

No very reliable agricultural statistics are available, but the area ordinarily cultivated is about 260 square miles, or rather more than one-fifth of the total area of the State. The principal crops are bajra and gram, the areas under which are usually about 58 and 57 square miles respectively; moth occupies 36 square miles, wheat about 25, barley nearly 20, rice 18, and jowar about 14 square miles. Cotton, poppy, and sugar-cane are cultivated to a certain extent, and san-hemp is extensively grown in the neighbourhood of the capital.

Karauli does not excel as a cattle-breeding country ; the animals are small though hardy, and attempts to introduce a larger kind have not succeeded as they do not thrive on the rock-grown grass. The goats alone are really good, and many are exported from the Dang to Agra and other places. Of the total area cultivated, 61 square miles, or about 23 per cent, are generally irrigated. Well-irrigation is chiefly employed in the country surrounding the capital. The total number of wells is said to be 2,813, °f which 1,645 are masonry; leathern buckets, drawn up with a rope and pulley by bullocks moving down an inclined plane, are universally used for lifting the water. Tanks are the principal means of irrigation in the rocky and hilly portions; there are said to be 379 tanks of sorts in the State, but only 81 of them have masonry dams. From tanks and streams water is raised by an apparatus termed dhenkli, consisting of a wooden pole with a small earthen pot at one end and a heavy weight at the other.

There are no real forests in the State and valuable timber trees are scarce. Above the Chambal valley the commonest tree is the dhao (Anogeissus pendula), but it is scarcely more than a shrub ; other common trees are the dhak {Bi/tea frondosa), several kinds of acacia, the cotton-tree {Bombax malabaricuni), the sal (Shorea robusta), the garjan {Dipterocarpus alatus), and the n'un (Me/ia Azadirachta). Near the Chambal in the Mandrael tahsll, and again in a grass reserve 20 miles north-east of the capital, a number of shlsham trees (Da/bergia Sissoo) are found together ; but they are, it is believed, not of natural growth. The so-called forest area comprises about 200 square miles, and is managed by a department called the Bagar, whose principal duties are to supply grass for the State elephants and cattle, find and preserve game for the chief and his followers, and provide a revenue by exacting grazing dues. The forest revenue averages about Rs. 6,400 a year, derived mainly from grazing fees, and to a small extent from the sale of grass and firewood, while the annual expenditure is about Rs. 3,000.

Red sandstone abounds throughout the greater portion of the State, and in parts, especially near the capital, white sandstone blends with it. Other varieties of a bluish and yellow colour are also found, the former near Machilpur, and the latter in the south and west. Iron ore occurs in the hills north-east of Karauli ; but the mines would not pay working expenses, and the iron manufactured in the State is smelted from imported material.

Trade and communication

Manufactures are not of importance. There is a little weaving and dyeing ; and a few wooden toys, boxes, and bed-legs painted with coloured lac, and some pewter and brass ornaments are turned out. The tat or gunny-cloth of Karauli is communications. . . well-known in the neighbouring marts, and a good deal is exported ; it is made from san-hemp grown near the capital.

The chief exports are cotton, ght, opium, zlra (cumin seed), rice and other cereals, while the chief imports are piece-goods, sugar, gur (molasses), salt, and indigo. The trade is mainly with the neigh- bouring States of Jaipur and Gwalior and with Agra District.

There is no railway in the State, the nearest stations being Hindaun Road on the Rajputana-Malwa line, 52 miles north of the capital, and Dholpur on the Indian Midland section of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, about 65 miles to the east. Apart from a few metalled streets in Karauli town, the only metalled road in the State is about 9 miles long. It runs north from the capital in the direction of Hindaun Road as far as the Jaipur border, and was completed in 1886 at a cost of Rs. 37,000. The rest of the roads are mere fair-weather tracks, some passable by bullock-carts, and others only by camels and pack-bullocks. The Chambal river is crossed by means of small boats maintained by the State, and the fare per passenger is usually about a quarter of an anna, the transit of merchandise being specially bargained for. There are five British post offices in the State (four having been opened in January, 1905), and that at the capital is also a telegraph office.

Famine

The State has been fairly free from famines, but has had its share of indifferent years. In 1868-9 tne rains crops failed, and there was considerable distress ; but the Maharaja did his best to mitigate the sufferings of the poor by establishing kitchens and poorhouses and starting public works. A sum of 2 lakhs was borrowed from the British Government ; the price of grain went up to 8 seers per rupee, and there was scarcity of fodder, especially in the highlands of the Dang, where nine-tenths of the cattle are said to have perished. The years 1877-8, 1883-4, 1886-7, and 1896-8 were periods of scarcity and high prices. In 1897 locusts did much damage ; and in the following year a pest called hala, akin to the locust, almost entirely destroyed the autumn crops in parts of the State. In 1899- 1900 distress was confined to a comparatively small area of 254 square miles, and never amounted to famine. Nevertheless, about 268,000 units were relieved on works ; and the total expenditure, including loans (Rs. 23,800) and land revenue remitted (Rs. 46,000) and sus- pended (Rs. 28,600), exceeded a lakh.

Administration

The State is governed by the Maharaja, assisted by a Council of five members. His Highness is President of the Council and has exercised full powers since 1889. Each of the five tahsils is under a tahsildar, and over the latter is a Revenue Officer or Deputy-Collector. In every village there is a State servant called a tahsildar, who is subordinate to the patwari of the circle in which the village is situated.

In the administration of justice the Karauli courts follow generally the British Indian enactments ; but certain sections have been added to the Penal Code, including one declaring the killing of cows and pea- fowl to be offences. The lowest courts are those of tahsildars^ who can try civil suits the value of which does not exceed Rs. 50, and on the criminal side can punish with imprisonment up to one month and with fine up to Rs. 20, or both. The court of the Judicial Officer, besides hearing appeals against the orders of tahsildars, can try any civil suit, and on the criminal side can sentence up to three years' imprisonment and fine up to Rs. 500, or both ; it can also pass a sentence of whipping not exceeding 36 stripes. The Council is the highest court in the State ; it hears appeals against the orders of the Judicial Officer, tries criminal cases beyond his powers, and, when presided over by the Maharaja, can pass sentence of death.

The revenue courts are guided by a simple code of law, introduced in 1 88 1-2, and amended by circulars issued from time to time by the Council to meet local requirements. Petty suits are decided by tahsildars subject to appeal to the Revenue Officer, who can also take up rent and revenue suits of any value or nature. As on the civil and criminal side, the highest revenue court is the Council.

The normal revenue of the State is about 5 lakhs, of which 2-8 lakhs is derived from land, one lakh from customs, and Rs. 23,000 as tribute from jagirdars. The normal expenditure is about 4-4 lakhs, the main items being cost of army and police (1-3 lakhs), gifts and charities (Rs. 70,000), cost of stables (Rs. 33,000), allowance to relatives (Rs. 29,000), and personal expenses of the chief (Rs. 28,000). The State, owing to a series of years of scarcity, is in debt to the extent of nearly 5 lakhs, which is being paid off by annual instalments of Rs. 55,000.

The State had till quite recently a silver and copper coinage of its own, and it is believed that coins were first struck by Maharaja Manak Pal about 1780. The distinctive mint-marks are the jhar (spray) and the katdr (dagger), and since the time of Madan Pal (1854-69) each chief has placed on his silver coins the initial letter of his name. The Karauli rupee, which in 1870 was worth half an anna more than the British, subsequently fell slightly in exchange value, and the Darbar resolved to introduce British currency as the sole legal tender in the State. The conversion operations have just been completed.

There are two main kinds of tenure in Karauli : namely, khdlsa, under which the State itself possesses all rights and privileges over the land ; and mudfi, under which the State has, subject to certain con- ditions, conferred such rights and privileges on others. Of the 436 villages in the State, 204 are khdlsa and 232 are mudfi. The latter tenure is of several kinds. The Thakurs or nobles pay as tribute [khandi) a fixed sum, which is nominally one-fourth of the produce of the soil, but really much less ; and this tribute is in lieu of constant military service, which is not performed in Karauli, though, when military emergencies arise or State pageants occur, the Thakurs come in with their retainers, who on such occasions are maintained at the expense of the Darbar. No tax is ordinarily exacted in addition to the tribute, except in cases of disputed succession, when nazardna is levied. This tenure is known as bdpoti ; and such estates are not permanently resumed except for treason or serious crime, though in the past they were frequently sequestrated for a time when the holders gave trouble. Another form of mudfi tenure is known as pandrth or religious grant. Under it land is granted in perpetuity free of rent and taxes. Other lands are granted on the ordinary jdglr tenure, while lands are also set apart to meet zandna expenses.

In the khdlsa area the

cultivating tenures of the peasantry are numerous. In some villages

a fixed sum is paid, varying according to the kind of crop and the

nature of the soil, and village expenses may be either included or

excluded ; in other villages an annual assessment is made by the

tahsildar, and the land revenue is paid sometimes in cash and some-

times in kind ; in other villages again the State merely takes a share,

varying from one-fifth to one-half, of the actual produce ; and lastly,

under the thekaddri or lambardari system a village, or a part of one, is

leased for a term of five or ten years to the headman or some individual

for a fixed sum payable half-yearly. Land revenue is nowadays mostly

paid in cash, and the assessment varies from Rs. 15 per acre of wheat,

sugar-cane, or poppy, to 1 2 annas per acre of moth or til. There is no

complete revenue survey and settlement in Karauli, but one has been

in progress since 1891.

No salt is manufactured in the State, nor is any tax of any kind levied on this commodity. By the agreement of 1882 the Maharaja receives Rs. 5,000 annually from the British Government as compen- sation, as well as 50 maunds of Sambhar salt free of cost and duty. The liquor consumed is mostly made from the flowers of the mahua {Bassia latifolid). The right to manufacture and sell country liquor is sold annually by auction, and brings in from Rs. 1,600 to Rs. 1,800; similarly the right to sell intoxicating drugs, such as ganja, bhang, &c, yields about Rs. 1,200. The revenue derived from the sale of court-fee stamps is about Rs. 6,000.

The only municipality is described in the article on Karauli Town. There is a Public Works department called Kamthaiia, but it is not now under professional supervision. A British officer was, however, usefully employed in 1885-6. The expenditure during recent years has averaged about Rs. 12,000 ; and the principal works have been tne metalled road to the Jaipur border in the direction of Hindaun Road (Rs. 37,000), the Neniakl-Gwari tank (about Rs. 23,000), a couple of bridges (costing respectively Rs. 17,000 and Rs. 30,000), and a building for a school (about Rs. 45,000).

The military force consists of 2,053 men. The cavalry number 260, of whom 171 are irregular; the infantry number 1,761 (1,421 irregular); and there are 32 artillerymen. Of- the 56 guns, 10 are said to be serviceable.

The State is divided into seven police circles or thatias, besides the kotwali at the capital. The police force consists of 358 men of all ranks, and there is in addition a balai in each village who performs duties similar to those of the chaukiddr in British India. The only jail is at the capital.

According to the Census of 1901, about 2-3 per cent, of the people were able to read and write : namely, 4 per cent, of the males and 0-2 per cent, of the females. The State maintains seven schools : namely, a high school and a girls' school at the capital, and primary schools at Mandrael, Karanpur, Sapotra, Kurgaon, and Machilpur. These are attended by nearly 400 pupils. Education is free, the annual expenditure being about Rs. 4,000. In addition, several private schools are attended by about 200 boys.

The State possesses five hospitals : namely, two at the capital (one exclusively for females), and three in the districts, at Machilpur, Mandrael, and Sapotra. They contain accommodation for 36 in- patients; and in 1904 the number of cases treated was 31,909, of whom 136 were in-patients, and 2,150 operations were performed.

Vaccination is nowhere compulsory. Three vaccinators under a native Superintendent are employed; and in 1904-5 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 5,865, or more than 37 per 1,000 of the population.

[P. W. Powlett, Gazetteer of Karauli (1874, under revision); H. E. Drake-Brockman, Gazetteer of Eastern Rajputana. States (Ajmer, 1905) ; Administration Reports of Karauli (annually from 1894-5).]