Khasi and Jaintia Hills

Contents |

Khasi and Jaintia Hills, 1908

Physical aspects

District in Eastern Bengal and Assam, lying between 24 degree 58' and 26 degree 7' N. and 90° 45' and 92° 51" E., with an area of 6,027 square miles. The District, which forms the central section of the watershed between the valleys of the Brahmaputra and the Surma, is bounded on the north by Kamrup and Nowgong ; on the east by Nowgong and Cachar ; on the south by Sylhet ; and on the west by the Garo Hills. To the north the hills rise gradually from the Brahmaputra Valley in a succession of a low ranges, covered with dense evergreen forest ; but on the south the Khasi Hills spring immedi- ately from the plain to a height of 4,000 feet, and form a level wall along the north of the Surma Valley. The Jaintia Hills slope more gently to the plain, but these also have no low outlying ranges. The southern and central portions of the District consist of a wide plateau between 4,000 and 6,000 feet above sea-level, the highest point of which, the Shillong peak, rises to 6,450 feet. On the north towards Kamrup are two similar plateaux of lower elevation. The general appearance of these table-lands is that of undulating downs. They are covered with short grass, but destitute both of the dense forest and of the high jungle with one or other of which waste land in Assam is almost invariably covered. Here and there are to be seen clumps of oak and pine, the hills are broken up with deep gorges and smiling valleys, and the scenery is not unlike that found in many parts of England. A considerable number of rivers rise in the hills, but are of little importance as a means of communication within the boun- daries of the District. The largest streams flowing towards the north are the Kapili, Barpani, Umiam or Kiling, and Digru, all o* which fall either direct or through other channels into the Kalang in Nowgong : and the Khri, which is called the Kulsi in Kamrup. To the south the best-known rivers are the Eubha, Bogapani, and Kynchiang or Jadukata. Where they flow through the plateau, the larger rivers have cut for themselves deep gorges of great beauty, whose precipitous sides are generally clothed with forest.

The Shillong plateau consists of a great mass of gneiss, which is bare on the northern border, but in the central region is covered by tran- sition or sub-metamorphic rocks. To the south, in contact with the

gneiss and sub-metamorphic, is a great volcanic outburst of trap, which is stratified and brought to the surface south of Cherrapunji. Still farther south are Cretaceous and Nummulitic strata, which contain deposits of coal and lime. The characteristic trees of the central plateau are those of a tem- perate zone. At an elevation of 3,000 feet the indigenous pine (Pinus Khasya) predominates over all other vegetation, and forms almost pure pine forests. The highest peaks are clothed with fine clumps of oak, chestnut, magnolia, beech, and other trees, which superstition has preserved from the axe of the wood-cutter. Azaleas and rhododen- drons grow wild, and many kinds of beautiful orchids are found in the woods. Wild animals include elephants, bison (Bos gaurus), tigers, bears, leopards, wild dogs, wild buffaloes in the lower ranges, and various kinds of deer.

The climate is cool and pleasant. In the hottest weather the ther- mometer at Shillong rarely rises above 80° and in the winter ice often forms. Snow seldom falls, but this is partly due to the fact that there is little or no precipitation of moisture in the cold season. Malaria lurks in the low ranges of hills on the north, but the climate of the high plateau is extremely healthy, and is admirably adapted to European constitutions.

There is no station in India where the recorded rainfall is as heavy as at Cherrapunji, on the southern face of the Khasi Hills. The average annual fall at this place is 458 inches ; but the clouds are rapidly drained of their moisture, and at Shillong, which is less than 30 miles away, it is only 82 inches. At Jowai, which lies at about the same distance south-east of Shillong, the average annual fall is 237 inches. The rainfall has never been recorded in the northern hills, but it is probably between 80 and 90 inches in the year. The District has always been subject to earthquakes, but all previous shocks were thrown into insignificance by the catastrophe of June 12, 1897. The whole of Shillong was levelled with the ground, masonry houses collapsed, and roads and bridges were destroyed all over the 1 ^strict. The total number of lives lost was 916. Most of these casualties occurred in the cliff villages near Cherrapunji, and were due to the falling of the hill-sides, which carried villages with them or buried them in their ruins.

History

On ethnological grounds there are reasons for supposing that the Khasis and Syntengs have been established in these hills for many centuries ; but, living as they did in comparative isolation in their mountain strongholds, little is known of their early history. At the end of the eighteenth century they harried the plains on the north and south of the District, and their raids were thus described by Pemberton in 1835 : — 'They descended into the plains both of Assam and Sylhet, and ravaged with fire and sword the villages which stretched along the base of this lofty region. Night was the time almost invariably chosen for these murderous assaults, when neither sex nor age were spared 1 .'

The Khasi Hills were first visited by Europeans in 1826, when Mr. David Scott entered into arrangements with the chiefs for the construction of a road through their territory from Assam into Sylhet. Work was begun; but in 1829 the Khasis took alarm at the threats of a Bengali chaprasi, who declared that the hills were to be brought under taxation. The tribes suddenly rose and massacred two Euro- pean officers, Lieutenants Bedingfield and Burlton, near Nongkhlao, with about 60 of their native followers. Military operations were at once commenced, but were protracted through several seasons, and it was not till 1833 that the last of the Khasi chiefs tendered his sub- mission. Engagements were then entered into with the heads of the various Khasi States. Their independence was recognized, Govern- ment abstained from imposing any taxation upon their subjects, and their territories were held to be beyond the borders of British India. Since that date the history of the Khasi States has been one of peace- ful development, only checked by the great earthquake of 1897. The Jaintia Hills lapsed to the British Government in 1835, when the Raja was deprived of the Jaintia Parganas in the District of Sylhet, on account of his complicity in the murder of three British subjects. For the next twenty years the Syntengs, as the inhabitants of the Jaintia Hills are called, were left almost entirely to their own devices. The administration was entrusted to their own headmen, who were un- doubtedly corrupt ; but the only tax levied was that dating from the Raja's time, which consisted of one male goat from each village. In i860 a house tax was imposed, as in the other hill tracts of the Province, and within a few months the people rose in open rebellion. Fortunately, a large force of troops was close at hand, and before the revolt could make headway it was stamped out. Scarcely, however, had the agitation subsided when the income tax was introduced into the hills. The total amount assessed was only Rs. 1,259, an ^ The highest individual assessment Rs. 9 ; but this was enough to irritate a people who had never been accustomed to pay anything but the lightest of tribute to their own princes, and who had never been taught by conquest the extent of the British resources. In January, 1862, a revolt began ; and, though apparently crushed in four months, it broke out again, and it was not till November, 1863, that the last of the

1 Report on the Eastern Frontier of British India, by Captain R. B. Pemberton, p. 221 (Calcutta, 1835). leaders surrendered, and the pacification of Jaintia could be said to be complete. Since that dale a British officer has been posted in the Jaintia Hills, and the people have given no trouble. Ch< rra punji was originally selected as the head-quarters of the hills, but the rainfall was found to be so excessive that the District officer moved to Shillong in 1864; and Shillong was constituted the head-quarters of the Administration when Assam was formed into a separate Province ten years later.

Population

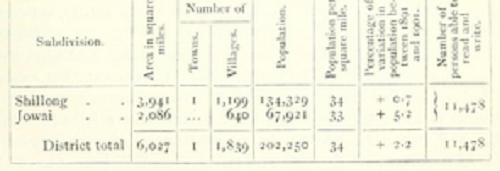

The population of the District, as returned at the last four enumera- tions, was: (1872) 140,356, (1881) 167,804,(1891) 197,904, and (ii)oi) 202, 2 qo. The slow rate of increase which occurred _ , . during the last decade was due to the unfavourable conditions prevailing after the earthquake of 1897. The first two enumerations were probably incomplete. The District contains two subdivisions, Shillong and Jowai, with head-quarters at places of the same names. Shillong (population, 8,384) is the only town, and there are 1,839 villages. The following table gives for each subdivision particulars of area, population, &c, according to the Census of 1901 :—

About 88 per cent, of the population of 1901 were still faithful to their tribal religion, 3 per cent, were Hindus, and nearly all the remainder Christians. The female element in the population is very large, and there were 1,080 women to every 1,000 men enumerated in 1 90 1, a fact which is probably connected with the independent position enjoyed by women. Of the total population, 59 per cent, spoke Khasi, a language which belongs to the Mon-Anam family, and 27 per cent. Synteng. The principal tribes were Khasis (107,500), Syntengs, a cognate tribe in the Jaintia Hills (47,900), and Mlkirs (12,800). The proportion of the population supported by agriculture, 76 per cent., is comparatively low for Assam ; but the Khasis are keen traders, and ready to earn money in any honest way.

The Khasis and Syntengs, like the other tribes of Assam, are descendants of the great Indo-Chinese race, whose head-quarters are supposed to have been in North-Western China between the upper waters of the Ho-ang-ho and the Yang-tse-kiang. They are, however, thought to belong to one of the earliest bands of immigrants, and their language is quite unlike any other form of tribal speech now found in Assam, but is connected with the Mon-Khmer language used by various tribes in Anam and Cambodia. While the rest of the horde pressed onwards towards the sea, the Khasis remained behind in their new highland home, and for many centuries have maintained their nationality intact, though surrounded on every side by people of a different stock. The tribe is subdivided into a large number of exogamous clans, which are in theory composed of persons descended from the same female ancestor. Each clan possesses distinctive religious rites, and a special place in which the uncalcined bones are buried after cremation. Politically, they are divided into a large number of petty States, most of which are ruled by a chief, or Siem, and some of which have less than 1,000 inhabitants. The Siemship usually remains in one family, but the succession was originally con- trolled by a small electoral body, constituted from the heads of certain priestly clans. Of recent years there has been a tendency to broaden the elective basis, and the constitution of a Khasi State has always been of a very democratic character, a Siem exercising but little control over his people.

In personal appearance the Khasis are short and sturdy, with great muscular development of the leg. The features are of a distinctly Mongolian type, with oblique eyes, a low nasal index, and high cheek bones. They are of a cheerful, friendly disposition, but, though peaceful in their habits, are unused to discipline or restraint.

Among many of the north-east frontier tribes there is little security of life and property, and the people are compelled to live in large villages on sites selected for their defensive capabilities. The Khasis seem, however, to have been less distracted by internal warfare, and the villages, as a rule, are small. The houses are low, with roofs nearly reaching to the ground, and are usually made of wooden planks. They are not built on platforms, as is commonly the case with the hill tribes ; but the floor is often made of boards, and the roofs of the well-to-do are covered with corrugated iron or oil tins beaten flat. The interior is generally divided into two compartments.

The men usually wear a sleeveless cotton shirt, a loin-cloth, and a wrap, and on their heads a turban, or a curious cloth cap with a peak over the forehead. The women are well clad in chemises and body- cloths, and both sexes often wear stockings with the feet cut off. The costumes brought out on gala days are most elaborate. The men wear silk loin-cloths and finely embroidered coats, while the women appear in really handsome silk cloths of different colours. The jewellery is massive, but handsome, consisting of silver coronets and pendants and heavy necklaces of coral and lac overlaid with gold. Their weapons are bows and arrows, with which they are always practising, swords, and shields. Their staple diet is dried fish and rice ; but they eat, when they can afford it, pork, beef, and any kind of game. Dog, however, they avoid, as, according to their legends, he was created to be the companion of man and his assistant in the chase. They drink large quantities of liquor, prepared from rice and millet, both fer- mented and distilled, and continually chew pan.

At a marriage the parties are pronounced man and wife in the presence of their friends, and a feast usually follows. The essential part of the ceremony consists in the mixing of liquor from two different gourds, representing the two contracting parties, and the eating by the bride and groom out of the same plate. The bride at first remains in her mother's house, where she is visited by her husband ; but when children are born, the parents, if they continue satisfied with one another, set up housekeeping together. This union between the sexes, however, can be terminated by mutual consent ; and as the initial ceremony costs but little, a man is not deterred from changing his wife by the expense of obtaining a new parTher. Divorce is very common, and is effected by a public declaration, coupled with the presentation by the man to the woman of five cowries or copper coins, which she returns to him with five similar coins of her own. He then throws them away. The public proclamation is occasionally dispensed with, and the marriage dissolved by the simple tearing of a pan leaf. The facility with which divorce can be obtained renders adultery or inter- course prior to marriage uncommon. Marriage, in fact, is merely a union of the sexes, dissoluble at will, and the people have no tempta- tion to embark on secret intrigues. A woman who commits adultery is, moreover, regarded with extreme disfavour ; and, according to the Khasi code of morals, there is only one thing worse, and that is to marry in one's own clan. A widow is allowed to remarry, but not into the family of her late husband, a practice exactly the converse of that prevailing in the Garo Hills, to the west.

The Khasis burn their dead, each clan or family having its own burning-ground. Two arrows are shot, one to the east and the other to the west, to protect the dead man, and a cock is sacrificed, which is supposed to show the spirit the way to the other world, and to wake him at dawn so that he may pursue his journey. The bones are subsequently collected from the pyre and removed to the common burial-place of the tribe. The stones erected to the memory of the dead form a special feature, being very numerous and often of great size; the largest are as much as 27 feet in height with an average breadth of nearly 7 feet. These monuments are of two kinds, some being tall upright monoliths, others flat slabs resting on smaller stones about 18 inches high. The monoliths are generally placed in rows, the central stone being erected in memory of the maternal uncle and one on either side in honour of the deceased and the deceased's father. As with all monuments, these stones are erected near villages and paths, where they will be most often seen. The matriarchal theory is in full force, and inheritance goes through the female line. A Siem is usually succeeded by his uterine brothers, and failing them by his sisters' sons. If he has no such nephews, the succession falls to his first cousins or grandnephews, but only to such as are cognates, his own sons and his kinsmen through the male line having no claim at all to the inheritance. So long as a man remains in his mother's house, whether married or unmarried, he is earning for his mother's family, and his mother or sisters and their children are his heirs. If, however, he is living separately with his wife, she and her daughters are entitled to succeed.

The natural religion of the Khasis, like that of most of the hill tribes, is somewhat vague and ill defined. They believe in a future state, but do not trouble themselves much about it. Misfortunes are attributed to evil spirits, and steps are at once taken to ascertain who is offended, and how he best may be propitiated. One of their most curious superstitions is that of the thlen. The tradition runs that there was once in a cave near Cherrapunji a gigantic snake or thlen, which caused great havoc among men and animals. At last, one man took with him to the cave a herd of goats, and offered them one by one to the monster. The snake soon learnt to open its mouth to be fed at a given signal, and the man then made a lump of iron red hot, threw it into its mouth, and thus killed it. The body was then cut up and eaten, but one small piece remained, from which sprang a multitude of thlens. These thlens attach themselves to different families, and bring wealth and prosperity, but only if they are from time to time fed on human blood. To satisfy this craving a human being must be killed, and the hair, the tips of the fingers, and a little blood offered to the snake. Many families are known or suspected to be ri thlen, or keepers of the thlen, and murders are not unfrequently committed in consequence of this awful superstition.

The people have shown themselves extremely receptive of Chris- tianity, but have little taste for Hinduism. One of their chief char- acteristics is a dislike of all restraint, including the restraint of tradition, which is of such binding force among most of the inhabitants of the East. There are few people less conservative than the Khasis, and they are ever ready to take up a novelty. To this healthy spirit of enterprise is due the marked progress they have made in the develop- ment of material comfort, and the extent to which they have outstripped the other tribes on the north-east frontier in their progress towards civilization. The Syntengs are very closely allied to the Khasis in langu religion, and customs. They are, however, less sturdily built and have darker complexions, the result, in all probability, of closer con- nexion with the plains. They owned allegiance to the Jaintia Raja, whose local representatives were twelve dollois or headmen ; but he received little in the way of tribute, and it is doubtful whether his influence in the hills was ever very strong.

The Welsh Presbyterian Mission, which has been established in these hills since 1841, has met with a large measure of success. The schools of the District are under the management of this society, which has succeeded not only in converting, but in imparting the elements of instruction to, a large proportion of the animistic population. In 1903 they had nine centres in the hills, at which twenty-one missionaries were employed. Of recent years a Roman Catholic mission has started work. The total number of native Christians in the District at the Census of 1901 was 17,125.

Agriculture

The soil of the Khasi Hills consists of a stiff clay, often indurated with particles of iron, which in its natural state is far from fertile. Manure is accordingly much prized, and cow-dung . . ,. is carefully collected and stored. Towards the east, the land becomes more fertile, and is often a rich black loam, and manure is not so necessary. In the more level valleys, in which the central plateau abounds, rice is grown in terraces and irrigated ; and such fields are also found on the northern margin of the District, wherever the conformation of the surface admits of them. Water is run on these fields in winter, to keep the soil soft and free from cracks. Elsewhere, the crop is raised on the hill-side. Turf and scrub are dug up, arranged in beds and burnt, and seed is sown in the ashes which serve as manure. In addition to rice, the principal crops are maize, job's-tears (Coix Lacrymd), various kinds of millet and pulse, and a leguminous plant called sohphlang {Flemingia vestita), which produces large numbers of tubers about the size of pigeons' eggs among its roots. Cotton is grown in the forest clearings to the north, and oranges, bay leaves, areca-nut, and pine-apples on the southern slopes of the hills. This portion of the District was much affected by the earthquake of 1897, and many valuable groves were destroyed by deposits of sand. There are no statistics to show the area under cultivation ; but the Khasis are energetic and enterprising farmers, and readily adopt fresh staples that seem likely to yield a profit. Potatoes were first introduced in 1830, and were soon widely cultivated. In 1882 nearly 5,000 tons of this tuber were exported from the hills, but a few years later blight appeared, and there has since been a great decrease in the exports. An experimental farm has been started near Shillong, and new varieties of potato introduced, which have been readily adopted by the Khasis. Peach- and pear-trees are grown in the higher hills, and efforts have recently been made to acclimatize various kinds of English fruit. A serious obstacle is, however, to be found in the heavy rainfall of May and June, and only early-ripening varieties are likely to do well.

The cattle are fat and handsome little animals, much superior to those found in the plains. The cows yield little milk, but what they give is very rich in cream. The Khasis do not milk their cows, and in many places do not use the plough, cattle being chiefly kept for the sake of the manure they yield, and for food. Ponies are bred, which in appearance and manners are not unlike the sturdy little animals of Bhutan. Pigs are kept in almost every house, and efforts have been recently made to improve the breed by the introduction of English and Australian animals.

Two square miles of pine forest near Shillong have been formally reserved, and there is a ' reserved ' forest 50 square miles in area at Saipung in the south-east corner of the Jaintia Hills. This forest is said to contain a certain quantity of nahor (Mesua ferred) and sam {Artocarpus Chaplasha), but up to date it has not been worked. Pine and oak are the predominating trees in the higher plateaux ; but this portion of the District is very sparsely wooded, the trees having been killed out by forest fires and shifting cultivation. The ravines on the southern face of the hills and the low hills to the north are, however, clothed with dense evergreen forest. The area of these forests is not known, but there is very little trade in timber.

Minerals

The mineral wealth of the District consists of coal, iron, and lime- stone. Iron is derived from minute crystals of titaniferous iron ore, which are found in the decomposed granite on the surface of the central dike of that rock, near the highest portion of the plateau. The iron industry was originally of considerable importance, but is now almost extinct. Cretaceous coal is found at Maobehlarkhar, near Maoflang, which is worked by the villagers in a primitive way for the supply of the station of Shillong. Another outcrop occurs at Langrin on the Jadukata river. Nummulitic coal is found at Cherrapunji, Lakadong, Thanjinath, Lynkerdem, Maolong, and Mustoh. The Maolong field, which is estimated to contain 15,000,000 tons of good workable coal, has lately been taken on lease by a limited company. Limestone is found all along the southern face of the hills as far as the Hari river, but it can only be economically worked where special facilities exist for its transport from the quarries to the kiln. Altogether thirty-four limestone tracts are separately treated as quarries. The most important are those situated on the Jadukata and Panatirtha rivers, the Dwara quarries, the Sheila quarries on the Hogapani, the quarries which lie immediately under Cherrapunji, and the Utma quarries a little to the east on an affluent of the Piyain. The stone is quarried for the most part during the dry months, and rolled down to the river banks. When the hill streams rise, it is conveyed in small boats over the rapids, which occur before the rivers issue on the plains. Below the rapids it is generally reloaded on larger boats and carried down to the Surma river, on the banks of which it is burnt into lime during the cold season. The earthquake of 1897 considerably increased the difficulties of transport, and the lime business has of recent years been suffering from a depressed market. The output in 1904 amounted in round figures to 123,000 tons. The quarries are worked by private individuals, usually them- selves Khasis, employing local labour. Stone quarries are also worked in the Jaintia Hills. Government realized in royalties in 1903-4 about Rs. 12,000 from lime, and Rs. 1,600 from coal.

Trade and communications

The manufactures of the District are not important. Handsome but rather heavy jewellery is made to order, and the Khasis manufacture rough pottery and iron hoes and daos, or hill knives. Cloths and jackets are woven in the laintia Hills from thread spun from the eri silkworm, and from cotton grown in the jhitins. Bamboo mats and cane baskets and sieves are also made.

The hillmen are keen traders, and a considerable proportion of the people earn their living by travelling from one market to another. The chief centres of business are at Cherrapunji, Laitlyngkot, Shillong, Jowai, and a market on the border of Sylhet near Jaintiapur. The principal exports are potatoes, cotton, lac, sesamum, oranges, bay- leaves, areca-nuts, and lime. The imports are rice and other food- grains, general oilman's stores, cotton piece-goods, kerosene oil, corrugated iron, and hand-woven cotton and silk cloths from the plains. There are a few Marwari merchants at Shillong, but they have no shops in the interior of the District, where trade is left in the hands of the Khasis and Syntengs.

An excellent metalled cart-road runs from Gauhati to Cherrapunji, via Shillong, a distance of 97 miles. The gradients between Shillong and Gauhati have been most carefully adjusted, and a tonga and bullock-train service is maintained between these two towns. Except in the immediate neighbourhood of Shillong, few roads are suitable for wheeled traffic; but in 1903-4 there were altogether 356 miles of bridle-paths in the District.

Administration

The District is divided into two subdivisions, Shillong and Jowai. Shillong is the head-quarters of the Deputy-Commissioner and the summer head-quarters of the Local Government. . . The Jowai subdivision is in charge of a European Subordinate Magistrate. In addition to these officers, an Assistant Magistrate is stationed at Shillong, and an Engineer who is also in charge of Kamrup District. The Jaintia Hills, with Shillong, and 34 villages in the Khasi Hills, are British territory. The rest of the Khasi Hills is included in twenty-five petty Native States, which have treaties or agreements with the British Government. These States vary in size from Khyrim, with a population of 31,327, to Nonglewai, with a population of 169. Nine of these States had a population of less than 1,000 persons in 1901.

The High Court at Calcutta has no jurisdiction in the hills, except over European British subjects. The Codes of Civil and Criminal Procedure are not in force, and the Deputy-Commissioner exercises powers of life and death, subject to confirmation by the Lieutenant- Governor. Petty criminal and civil cases, in which natives of the District are concerned, are decided by the village authorities. Serious offences and civil suits in which foreigners are concerned are tried by the Deputy-Commissioner and his Assistants. There is, on the whole, very little serious crime in the District, but savage murders are occasionally committed.

Land revenue is assessed only on building sites and on flat rice land in the Jaintia Hills, which pays Rs. 1-14 per acre. The principal source of revenue in British territory is a tax of Rs. 2 on each house. The revenue from house-tax and total revenue is shown in the following table, in thousands of rupees : —

- Exclusive of forest revenue.

There are police stations in the hills, at Shillong, Cherrapunji, and Jowai, and an outpost at Nongpoh, half-way between Shillong and Gauhati. The force has a sanctioned strength of 23 officers and 183 men, who are under the immediate charge of the Deputy-Com- missioner, but ordinary police duties are discharged by the village officials. The only jail in the District is at Shillong ; it has accommo- dation for 78 prisoners.

Thanks to the efforts of the Welsh Presbyterian Mission, education has made considerable progress, and in 1901 the proportion of literate persons (5-7 per cent.) was higher than that in any District in Assam. The number of pupils under instruction in 1880-1, 1890-1, 1900-1, and 1903-4 was 2,670, 3,582, 6,555, and 7, 2 75 respectively. The Khasi Hills owes its position to the spread of female education, 3-4 per cent, of the women being able to read and write, as compared with 04 per cent, in Assam as a whole. In 1903-4 there were 348 primary, 8 secondary schools, and one special school in the District. The number of female scholars was 2,395. ' ' 1<J great majority of the pupils under instruction were only in primary classes. Of the male population of school-going age 28 per cent, were in the primary stage of instruction, and of the female population of the same age 14 per cent. The total expenditure on education was Rs. 1,21,000, of which Rs. 7,000 was derived from fees ; about 40 per cent, of the direct expenditure was devoted to primary schools.

The District possesses two hospitals and four dispensaries, with accommodation for 23 in-patients. In 1904 the number of cases treated was 25,000, of whom 200 were in-patients, and 500 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 10,000, the greater part of which was met from Provincial revenues. Vaccination is compulsory only in Shillong town, and has been somewhat neglected in the District. In 1903-4 only 28 per 1,000 of the population were protected, as compared with 44 per 1,000 in Assam as a whole.

[A. Mackenzie, History of the Relations of the Government with the Hill Tribes of the North-East Frontier of Bengal (Calcutta, 1884); W. J. Allen, Report on the Administration of the Cossyah and Jy/iteah Hill Territory (Calcutta, 1858); J. D. Hooker, Himalayan Journals (1854); B. C. Allen, District Gazetteer of the Khdsi and Jaintia Hills (1906) ; Major P. R. T. Gurdon, The Khdsis (1907).]

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.