Lohar, Chota Nagpur

Contents |

Lohar, Chota Nagpur

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Tradition of origin

The blacksmith caste of Behar, Chota Nagpur, and Western Bengal. The Lohars are a large and heterogeneous aggregate, comprising members of several different tribes and castes, who in difftlrent parts of the country took up the profession of working in iron. Of the various sub-castes shown in Appendix I, the Kanaujia claim to be the highest in rank, and they alone have a well-mn.rked set of exogamous sections. They regard Viswamitra as their legendary ancestor, and worship him as the tutelary deity of their craft. The Kokas Lohars seem to be a branch of the Barhis, who have taken to working in iron and separated from the parent group for that reason. The Magha iya seems to be the indigenous Lohars of Behar, or opposed to the Kananjia and Mathuriya, who profess to have come in from the North-West Provinces. Kamar-Kalla Lohars may perhaps be a degraded offshoot from the Sonar caste. The Mahur or Mahulia say they came from the North-Westeru Provinces, and the fact that all Hindus can take water from their hands renders it likely that they may have broken off from some comparatively respectable caste.

Internal structure

Their traditions, however, are not definite enough to enable this conjector to be verified.. The Kamia Lohars found in Champaran have immigrated from Nepal, and are regarded as ceremonially unclean. Many of them have become Mahomedans. In the San tal Parganas, a sort of ethnic border land between Bengal and Behar, we find three sub¬castes of Lohars,-Birbhum ia, from the neighbouring district of Birbhum; Govindpuria., from the subdivision of Govinupur, in Northem Manbhum; and Shergarh ia, from the pm•ganG. of that name in Bardwan. '1'he names give no clue to the tribal affinities of these three groups, but the fact that they have the totemistic section Sal-machh shows them to be of non-Aryan descent, probably Bauris or Bagdis, who took to iron-working and called themselves Lohars. Of the four sub-castes into which the Lohars of Bankura are divided, two bear the names Gobra and Jhetia., which occur among the sub• castes of the Bauris. Two others-Angaria and Pansili¬I am unable to trAce. The Manbhum Lohars acknowledge three sub¬castes,-Lohar-Manjhi, Danda-Manjhi, and Bagdi-Lohar, names which suggest a connexion with the Bagdi caste. Lastly, in Lohar¬daga. we bave the Sad-Lohars, claiming to be immigrant Hindus; the Manjhal-Turiyas, who may well bev a branch of the Turi caste; and the Munda-Lohars, who are certainly Mundas. The great number of the sub castes,' coupled with the fact that in some cases we can determine with approsimate certainty the tribes of which they once formed part, seem to point to the conclusion, not merely tbat the aggregate termed the Lohar caste is made up of drafts looally levied from whatever groups were available for employment in a oomparatively menial occupation, but that all castes whose functions are concerned with the primary needs of social life are the result of a similar process.

Marriage

Further indications of the different elements from which the caste has been formed may be traced in its social customs. The Lohars of Chota Nagpur and Western Bengal practise adult as well as infant-marriage, a price is paid for the bride, and the marriage ceremony is substantially identical with that in use among the Bagdis. Polygamy they allow without imposing any limit on the number of wives a man may have, and they reoognize the extreme lioense of divoroe charaoteristio of the aboriginal raoes. In Behar, on the other hand, infant-marriage is the rule and adult-marriage the rare exoep¬tion. The ceremony is modelled on the orthodox type. A bridegroom¬prioe is paid, and polygamy is lawful only on failure of issue by the first wife. As to divoroe, Fome diVl'rsity of praotioe seems to prevail. Kanaujias profess to prohibit it altogether, while other sub•oastes admit it only with the permission of the pancbayat, and regard the remarriage of divorced wives with disfavour. Widow-marriage is reoognized both in Behar and elsewhere; but this is by no means a distinotively Dravidian usage, but rather a survival of early A.ryan custom, whioh has fallen into disuse among the higher castes under the influence of Brahmanical prejudice.

Religion

Equally oharaoteristio differenoes may be observed in the religi¬ ous usages of the main branohes of the caste. Kanaujia Lohars and all the Behar sub-oastes, exoept the Nepalese Kftmias, pose as orthodox Hindus, employ Maithil Brahmans, and worship the standard gods. In Chota Nagpur and Western Bengal, though some profession of Hinduism is made, this is little more than a superfioial veneer laid on at n very reoent date, and the real worship of the ca te is addressed to Manasa, Ram Thakur, Baranda Thakur, Phulai Gos1iin, Dalli Gorai, Bhadu, and Mohan Giri. In the latter we may perhaps recognize the mountain god (Marang Buru) of the Mundas and Santals. To him goats are sacrifioed on Mondnys or Tuesdays in the months of Magh, A.sbar, and Agrahayan, the flesh being after¬wards eaten by the worshippers. The Lohars of Bankura and the Santal Pargan8.s have taken to employing low Brahmans, but in Lohardaga the aboriginal priest (pahan) and the local soroerer (mati (ojha soklui) minister to their spiritual wants. The Sad-Lohars alone show an advance in the direction of orthodoxy, in that they employ the village barber to aot as priest in the marriage ceremony.

Occupation

In Behar the oaste work as blaoksmiths and carpenters, while many have taken to cultivation. They buy. their material in the form of pigs or bars of iron. Iron-smelting is confined to the Lohars of Chota Nagpur, and is supposed to be a muoh less respeotable form of industry than working up iron whioh other people have smelted. In the Santa.l Parganas Lohars often cultivate themselves, while the women of the household labour at the forge. None of the Western Bengal Lahars combine carpentry with working in iron.

Social status

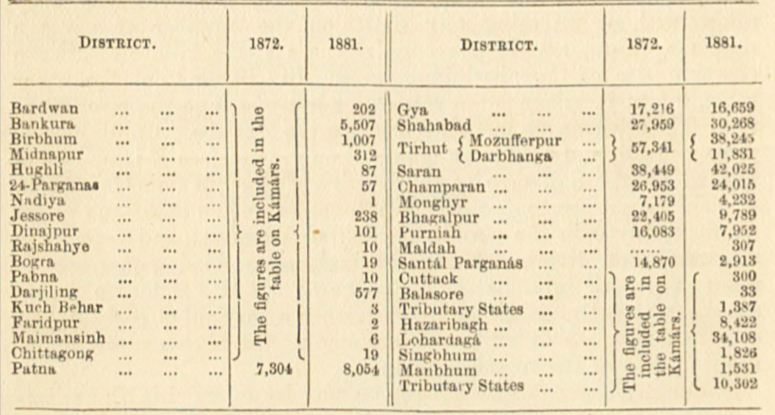

In Behar Lohars rank with Koiris and Kurmis, and Brahmans take water from their hands. The status of the caste in Western Bengal is far lower, and they are assooiated in matters of food and drink with BaUl-is, Bagdis, and Mals. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Lohars in 1872 and 1881 :¬