Madiga:Deccan

Contents |

Madiga

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

(Male Titles : Appa, Ayya. Female Title : Amma.)

Madiga, Madigowd, Madigaru, Madru, Dher, Chandal, Antyaja, Ettlwandlu, Peddintiwandlu, Panchamollu, Matangi Makallu, Gosangi, Kamathi, Bendar, Chambhar — a very numerous caste of leather-workers and rope-makers, many of whom are engaged as village watchmen and musicians. They are to be found scattered all over the Telugu and the Karnatic portions of H. H. the Nizam's Dominions, and correspond, in every detail, to the Mang caste of the Maratha Districts. Some of the synonyms, which stand at the head . of this article have reference to the occupations the members of the caste have pursued. The name ' Ettiwandlu ', for example, signifies those who do the etti or begari (forced) work. ' Chambhar ' is a corruption of the Sanskrit word ' Charmakar,' which means ' a worker in leather ' , and the word ' Kamathi ' indicates that they are menials. Some, such as, ' Chandal,' ' Antyaja ' (lowest born), ' Gosangi ' {gao, cow, and hansaka, killer), and ' Dher ' are opprobrious titles applied to them by others to indicate their lowest status in Hindu society. To dignify themselves, the members of the caste have assumed such epithets as Matangi Makkalu, the children of Matangi, the daughter of their mythical ancestor Jambavan ; Panchamollu, or members of the fifth caste, as distinguished from the four shastric divisions of mankind (Brahman, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra) ; and Peddintiwandlu, or dwellers in big houses. Madigas, who are enrolled in the Indian army, call themselves Bendars, with the object of concealing their true caste.

Origin

The etymology of the name ' Madiga ' is uncertain, although attempts are made to derive it from the word ' Matanga , the name of an aboriginal tribe, mentioned by ancient authorities as descended from the illicit connection of a Plava father and Antivasiya mother. The legends of the Madigas, probably of rec;ent invention, give no clue to their origin or early history. According to one, the Madigcis trace their parentage to Jambavant, who was believed to be the primeval creation of Narayen, the supreme god, and to have existed when the whole world was water and there was neither the earth, nor the sun, nor other luminaries. Jambavant once perspired, and from the perspiration came forth ' Adi Shakti ' (primeval energy), who laid three eggs, from which sprang' Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesha. Brahma created ten sages who became the progenitors of mankind. The names of these Maha Munis are : — (1) Chapala, (2) Taraila, (3) Brahma, (4) Neela, (5) Paia, (6) Bhadrachi, (7) Raktachi, (8) Gola, (9) Jamadagni and (10) Parshuram, and from the first sprang the Madigas, while the Brahmans are the descendants of the last. Another story relates that Jambavant (Zalazam) had seven sons; Brahma, with a view to create the world and people it, killed Heppu Muni, one of the sons, and from the mixture of his blood with water evolved the solid earth. Brahma»then killed another son named Jala Muni and his life stream changed into a' stream of water. The mountains were created from Ghata Muni's blood, blood from Rakat Muni, milk from Pal a Muni, and an indigo colour from Neela Muni, until at last from the blood of Gava Muni came the Madigas, the first representatives of mankind. A third account states, that, once upon a time, when Parvati and Parameshwar were on a ramble, Parvati becoming unclean, was obliged to leave her menstrual clothes under a tree and from these garments sprang Chinnaya, whom the heavenly pair engaged to tend their divine cow, Kamadhenu. Chinnaya once tasted the cow's milk and found it so delicious that he was ten-pted to kill the cow itself and eat its flesh. He imme- diately carried his impious design into effect, but the carcass of the cow was so heavy that none, not even the gods, could move it. Siva thought of Jambavant who was practising penance, and called out to him, ' Mahadigaru ' (lit — a great one come down). Jambavant, who thus obtained the name Mahadiga or Madiga, appeared at Siva's call, lifted the dead body, and cut it into pieces. Siva ordered Chinnaya to dress the beef, and invited all the gods to a feast. But Chinnaya, unfortunately, while trying to blow down an effervescence, at into the cooking p)ot and the gods, observing this, left the dining hall. Siva, in anger, cuised both Chinnaya and Jambavant for their negligence and degraded them to the lowest taste. Chinnaya's descendants are called Malas, while Jambavant became the ancestor of the Madigas, and as Jambavant ate the leavings of Chinnaya and drank water after him, the Madigas are ranked below the Malas in point of social standing

Internal Structure

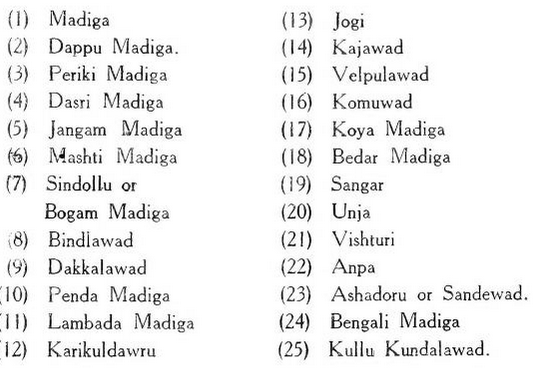

The Madigas have two main divisions Canara Madigas, and Telugu Madigas, who neither intermarry nor eat together. Each of these is broken up into numerous sub-tribes which vary greatly in different districts. Some of these are shown below : —

This list is in no way exhaustive. The Madiga community is a large one and distributed over a very extensive area, and to this fact are probably due the numerous groups into which it is divided. The origin of these sub-castes is obscure and very difficult; of deter- mination owing to the extreme repulsion with which the caste is regarded by all Hindus. Some of the names, such as Lambada, Koya, Bedar have reference to the castes from which the sub-castes have been recruited, while others are based upon the professions the sub-castes have followed.

The Madiga sub-caste, found everywhere m the Karnatic and Telingana, represents, probably, the original nucleus of the caste.

They earn their livelihood by making sandals, leather ropes and buckets and other leather articles.

The Mashti Madiga, jaladohi, are story tellers and beggars, occasionally exhibiting acrobatic feats before the public.

The Sindollu, Chindiwandlu, or Bogam Madiga, are the courte- zans of the Madiga caste ; they attend all Madiga ceremonies and entertain the public by singing and dancing. They maintain them- selves also by prostitution. Their name Sindi, or Sindollu, is said to be derived from ' Sairandhri,' the Sanskrit word for prostitute.'

The Ashadoru, or Sandewad, are vagrant beggars who obtain alms by performing plays based upon stories from the BfiagWat.

The Bengali Madigas are a wandering class of jugglers and conjurers and appear to have no cormection with the Madigas, but derive their name from Bengal, whence they probably came. They are doubtless enrolled among the Madigas because they occupy the lowest position in Hindu society.

The Bindalas, or Bindlawad, discharge the'functions of priests to the Madiga caste and perform their religious rites to 'the music of the jamadke, a musical instrument characteristic of their profession. Occasionally, they profess to be possessed and to fortell events and exorcise ghosts.

The Penda Madigas are sweepers by profession.

The Dappu Madigas seem to be identical with the Lambada Madigas, and are attached to each Lambada tanda (camp). They act as musicians to the Banjara tribes, playing at their religious cere- monies, on the daphada, a sort of drum.

The Karikuldawaru make articles from horns.

The Jogis, or joginis, are boys and girls devoted to the service of particular deities in fulfilment of vows made in sickness or affliction. The girls, after their dedication, take openly to prosti- tution and incur no social disgrace on that account.

The Periki Madigas assert that they are so called because their ancestors ran away from the marriage of Vashistha and Arundhati to escape the rain of fire that fell on the occasion.

The Kullu Kundalawad are so called because they are engaged as carriers of earthen pots filled with shendi (the juice of the wild date palm) to the market. This occupation has degraded them and no pure Madiga will eat or marry with them.

The Dasri Madigas are gurus, or spiritual advisers to those Madigas who profess to belong to the Vaishanava sect. They occupy the highest social level among the caste and stand in hyper- gamous relation to their disciples. They abstain from beef.

The Jangam Madigas trace their lineage from Nulka Chandaya, who was the first Madiga proselyte to the Lingayit creed. Nulka Chandaya was a devout worshipper of the god Siva, and fed Jangams daily with the money he earned by selling ropes and sandals and Siva, as an act of grace, made him a Jangam. The Jangam Madigas claim for themselves the highest social position, and minister to the spiritual needs of the Shaiva Madigas or Madiga Vibhutidharis. Like the Dasris, they abstain from beef, and do not interdine with other members of the caste. It is said that they accept girls in marriage from other sub-castes, but do not give their own daughters in return.

The Dakkalawads are wandering beggars, who appear to be a degraded branch of =the Madigas and beg only from them. They are also the genealogists or custodians of the gotras of their parent caste. Regarding their origin, it is said that Heppu Muni, the eldest son of Jambavant, after being killed by Brahma for the creation of worlds, was restored to life by his father, but was degraded and condemned to subsist by begging from, and reciting the mythical history of, the Madiga and Manga castes. They extract alms as an hereditary right, and should any Madiga decline to give them their due, they mount his effigy on a bamboo pole and set it up in front of his house. Standing in the neighbourhood, they hurl at him horrible imprecations and curses ; he remains under the ban of his caste and no one dares to maintain any communication with him until he thoroughly satisfies the demands of the refractory beggars. The Dakkalawads say that they have only one gotra ' Gangadhar.' They bear an evil reputation as criminals and are vigilantly watched by the police. They are regarded as outcastes by the Madigas and are not allowed to enter their quarters, but they pitch their huts of bamboo mats at a distance from the Madiga houses.

The Gond Madigas, Koya Madigas, Lambada Madigas and Bedar Madigas may either represent the lowest strata of their respective tribes, or they may be originally Madrgas who were converted to, and were gradually absorbed into, their adopted tribes. The members of these sub-castes do not intermarry, although inter- dining in certain cases is allowable.

The exogamous sections of the caste are mostly of the territorial type, but some of them are totemistic, although the totems are not generally held as taboo by the members of the sections bearing their names.

A few of the sections are as follows : — Territorial. Totemistic.

Mukapalli. Ullello (onions).

Yelpukonda. Kumollu (horn).

Malangurollu. Amdyarollu (castor plant).

Kunagoilawaru. Gatollu (hill).

Sultanpurwaru. KatkooroUu (sword).

Boyampalliwaru. Gaddapollu (beard).

Nagaipalliwaru. Awalollu (cow).

Danduwaru. Pasupalliwaru.

A Madiga cannot marry outside the sub-caste nor inside the section to which he belongs. This simple rule of exogamy is sup- plemented and a man may marry the daughter of his elder sister or maternal uncle or paternal aunt. Two sisters may ciso be married to the same m?in.

Members of other castes are received by the Madigas into their community by their giving a feast to the Madigas of the neighbourhood. Before the feast, a betel leaf is cut on the tongue of the novice who is subsequently required to wait upon his new associates, to eat with them and remove their dishes. The hut in which this ceremony takes place is burnt.

Marriage

The Madigas practise both infant and adult marriage, but the former usage is deemed the more respectable and is gradually coming into vogue. Girls for whom husbands cannot be procured, or who are vowed by their parents to the tervice of temples, are dedicated to their tutelary deities. Such girls are called Joginis or Basavis, and are sometimes married to an idol and sometimes to a dagger. The girl, who is to undergo the ceremony, is dressed in new clothes and taken to the temple. Her forehead is smeared with kunkum (red lead powder), a lighted lamp is waved round the idol or the dagger, and the girl, bearing the lamp on her head, walks three times round the symbol of the deity. The Joginis become prosti- tutes, but their children are admitted to the full privileges enjoyed by the legitimate members of the caste. Unmarried girls, becoming pregnant, are also devoted to the service of gods. A girl on attaining puberty is unclean for five days. On the 5th day she bathes, touches a green leaf and becomes ceremonially pure.

Polygamy is recognised, and a man is permitted to marry ai many wives as he can afford to maintain. The second wife is usually a widow or a divorcee. A bride-price, varying in amount from Rs. 5 to Rs. 15, is paid to the parents of the girl.

The marriage ceremony differs in different districts, but in each district it is a copy of the ritual in vogue among the middle classes of Hindus. '

The initiative towards marriage is taken by the bridegroom's father, who sends a party of five men to select a suitable girl for his son and settle the match. After the girl is selected, the boy's father, with his relatives, goes to the girl's house and presents her with a sari and a choli. in confirmation of the match, the caste panchas are entertained with Ifhushali, or drink, the expenses of which are shared by both, the bridegroom's father contributing double that of the bride's father. A Brahman astrologer is consulted, and a lucky day is fixed for the celebration of the wedding. A goat is killed as a sacrifice to Pochamma, who is worshipped with offerings of the goat's blood mixed witli a quantity of liquor. The goat's head becomes the perquisite of a dhohi (washerman) while the body is cooked and partaken of by the members of the family. Other deities, such as Ellamma, Pedamma, Mutyallamma and ancestral spirits, are invoked to bless the betrothed couple. On the appointed day, the bride is taken in procession to the bridegroom's house where, on arrival, the salawadi, the priest of the caste, lifts her from the horse, waves rice and turmeric round her face, sprinkles water on her body and places her on a seat under a wedding canopy of eleven posts. At the auspicious moment fixed for the wedding, the bridal pair are made to stand face to face, in a large bamboo basket, containing Indian millet, and a cloth is thrown over them so as to conceal their faces from the assembled guests. In this position, they are encircled five times, twice, with raw cotton thread. After this has been done, the cloth is removed and the young couple are taken out of the basket. The cotton thread is made into two bracelets (kankams) and one of them is fastened, with a piece of turmefic, on the wrist of the bridegroom and the other, in like manner, on that of the bride. This simple primitive usage is followed by an ortiiodox one, and the c&uple are made to stand face to face on a wooden plank, a cloth is held between them and the mehetarya, or elderly member of the caste, officiating as priest, throws grains five times over their heads. This last ritual is believed to be the essepijal portion of the ceremony and is followed by other rites, including Myalapolu, Kottanam, Brahma- modi, Dandya, Panpu. NagocUy, Vappagintha, Vadibium and others, all of which have already been fully described in the articles on other castes The ceremony is closed with a feasi, at which a « great deal of drinking and merry-makinE prevails.

In the Karnatic. the marriage ceremony comprises : —

(1) Pod. — The goddess Ellamma is invoked and a piece of leather is tied, in her honour, about the neck of an old woman.

(2) Nischiiartha. — The confirmation of the betrothal, at which

the girl is presented with Rs. 2 by the bridegroom's party. (3^ HogHoppa. — ^The fixing of an aulspicious day for the celebration of the wedding.

(4) Uditomba. — The girl is presented with cocoanuts and rice

and escorted in procession to the house of the bridegroom.

(5) Patiarshina. — The bridal pair are smeared with turmeric

paste and oil, and \ank.anams (thread bracelets) are fastened on their wrists.

(6) Maniaoana. — The bridal pair, with their mothers, are

nibbed with oil and bathed, being seated within a square formed by placing four earthen vessels filled with water at the four corners and by passing a cotton thread seven times round their necks. The thread is removed, and with it, as well as with a pearl, the water from the pots is sprinkled on their heads. This ceremony is known as Mani-neera or pearl-water. The maternal uncle of the bridegroom then plants a twig of the banyan {Ficus bengalensis) under the booth and worships it.

(7) Gone. — The "bride and the bridegroom stand facing each

other in bamboo baskets containing Indian millet (jawart) and a figure of ' Nandi ' (Shiva's bull) is traced on the ground between there. Some milk is poured on the heads of the couple and the mangahutra (lucky thread) is tied about the girl's neck by the Jangam or Dasri, who officiates as priest. The bride and bridegroom then sprinkle rice over each other's head and this forms the binding portion of the ceremony.

(8) Bhiuma.— Wheat cakes and sweets are offered to the patron deity and four persons of the bridegroom's party and five of the bride's are required to eat the offerings. Any- thing remaining is buried underground.

(9) Mirongi. — The bridegroom, on horseback, and the bride, on foot, go in procession to Hanuman's temple and, after worshipping the god, return home.

(10) A square is formed by placing an earthen pot at each corner and a cotton thread is passed round. Within this, the wedded couple are seated and bathed, their kanka- nams are untied and then transferred to the banyan twig previously planted under the booth,

(11) Chagol. — The feast given to the caste people and rela- tives of the bride, after which the bride leaves her husband's house, where the wedding ceremony was per- formed, and goes to her father's house. This rite com- pletes the marriage ceremonies. Tera, or bride-price, varying from Rs. 7 to Rs. 100, is paid to the girl's parents.

The Dakkalwad marriage presents some interesting features. The bridle and bridegroom, dressed in wedding clothes an4 with their garments knotted, walk three times round a wooden pestle placed beneath the marriage canopy. They are then seated beside the pestle and grains of rice are thrown on their heads by the assembled relatives and guests. Upon this, the couple undergo ablution and the bridegroom ties the pusti (mangalsutra) about the bride's neck, the women of the household singing songs all the while. The father of the girl receives Rs. 10 as the price of his daughter.

Widow-'Marriage

Widows are allowed to marry again, but they are not expected to marry their deceased husband's youflger brother. On a dark night, the bridegroom's party go to the widow's house, present her with a white sari, choli and bangles and escort her to the bridegroom's house. There the couple are bathed, and the bridegroom ties a pusti of gold round the widow's neck. Next morning the pair conceal themselves in a forest grove, and at night return to their house. After her marriage, a widow cannot claim the custody of her children by her late husband.

Divorce

Divorce is permitted, generally, on the ground of the wife's adultery, and is effected by driving her out of the house before the caste Panchayat. Divorced women are allowed to marry again by the same rites as widows. The morality of the Madiga women is, however, very lax ; adultery among them is not looked upon with abhorrence and is usually punished only with a nominal fine.

Inheritance

Among the Madigas, the devolution of property is governed by the Hindu law of inheritance. A Jogini, or dedi- cated girl, shares her father's property equally with her brothers, with succession to her children. Wills are unknown. A childless man usually adopts his brother's son, failing whom, any boy of his own section, but in any case the adopted boy must be younger than the adopter.

Religion

The Madigas are still animistic in their belief, and pay more reverence to the deities of diseases and ghosts and spirits of deceased persons, than to the great gods of the Hindu pantheon. Their tribal deity is Matangi, who is believed to be the female progenitor of the caste. Regarding her, it is said that she gave protection to Renuka, when the latter was pursued by her son Parshuram fit his father's command. Parshuram, in wrath, cut off Matangi's nose, which was immediately restored to her by Renuka. Since then, Renuka, in the form of Ellamma, has been revered as their patron deity by the caste. Next in honour to Matangi are, Mari Amma, Murgamma or Durgamma, the goddess presiding over chil- dren, whose worship has been fully described in the report on the Manga caste, Pochamma, the deity of small-pox, Maisamma, Ellamma, Gauramma, and Mahakalamma. To Mari Amma are offered goats and bull-buffaloes in the month of Ashadha. Pochamma is worshipped on Mondays, Ellamma on Tuesdays, and Maisamma on Sundays, with offerings of goats, buffaloes, fowls and liquors, which are subse- quently partaken of by the votaries themselves. Bindlas officiate as priests, and perform all religious and ceremonial observances.

Besides these greater animistic deities, the Madigas propitiate a number of ghostly powers, with a variety of sacrifices, Erakala women being engaged to identify and lay the troubling ghost. Honour is also done by .the members of the caste to the standard Hindu gods, amtjng whom may be especially mentioned Hanuman and Mahadeva. Muhammadan saints and pirs are also appeased by the members of the caste.

Like other Telaga castes, the Madigas are divided between Tirmanidharis and Vibhutidharis. The Tirmanidharis are under the guidance of Mala Dasris, while the Vibhutidharis, or Shaivaits, acknowledge Mala Jangams as their spiritual gurus.

Disposal of the Dead

The dead are usually buried, except in the case of women in pregnancy and lepers, who Me burnt. Married agnates are mourned for ten days, and unmarried for three days. No Sradha is performed, but birds are fed with cooked flesh on the 3rd day after death. During the period of mourning, the chief mourner may not eat flesh, molasses, oil or turmeric nor may he sleep on a bed. On the 10th day after death, a feast is given to the caste people and purification is obtained. It is said that the Namdharis burn their dead in a lying posture, with the head pointing to the south, collect the ashes and bones on the 3rd day after death, and either throw them into a sacred stream or bury them underground. Bindalwads are employed to perform the funeral rites.

Social Status

The social rank of the Madigas is the lowest in the Hindu social system. They eat the leavings of any caste except the Erakalas, Domars, Pichakuntalas, Buruds, Jingars and Panchadayis, while no caste except the Dakalwads, their own sub- division, will eat food cooked by them. They live on the outskirts of villages, in thatched one-storied housef, with only one entrance door. Their habits are very dirty, and their quarters extremely filthy. The village barber will not shave their heads nor will the village washerman wash their clothes and they have to employ barbers and washermen from among their own community. Their touch is regarded as unclean by all respectable classes, and a Brahman touched by a Madiga is required to obtain purification by bathing himself, washing his clothes and changing his sacred thread for a new one. The diet of a iVladiga is in keeping with his degraded position and he eats beef, horse flesh, pork, fowls, mutton, and the flesh of animals which have died a natural death. The bear, as a representative of their ancestor Jambavant, ij held in special respect, and no Madiga will injure or kill the animal.

Occupation

The original occupation of the caste is believed to be the skinning of dead animals, leather dressing and the making of leather ropes, leather buckets for hauling water from wells and other leather articles used in husbandry. Like the Malas they are field servants, and supply the farmers with the above articles, for which they get, as their perquisite, a fixed quantity of grain for each plough. They make shoes of various kinds, but especially chapals (sandals) of which they produce the best varieties. They are engaged as scavengers, village watchmen, guides, executioners and begaris, or forced coolies. They also serve as musicians at the maniage and other ceremonies of high caste' Hindus. Their right to carcasses is often disputed by the Malas and tedious litigations result. At some places they hold Inam lands, in lieu of services rendered by them to the village community as messengers and carriers. They also work as village criers, announcing by beat of drum {da^ada) any public orders. Some of them get enrolled in the Indian army, where they pass under the name of Bedars or Gosangi Bantus. Many serve as menials in the houses of Muhammadan landlords. A few only have taken to agriculture.