Mal, Central Bengal

Contents |

Mal, Central Bengal

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

A Dravidian cultivating caste of Western and central Bengal, many of whom are employed as Chaukidars or village watchmen and have gamed an evil reputation for their thieving propensities. Beyond the vague statements current among the Mals of Eastern Bengal, that they were wrestlers (Malla, Mala) at the court of the Dacca Nawabs and gained their name from this profession, the caste appear to have no traditions, and their origin has formed the subject of much discussion, the general drift of which is stated by Mr. Beverley l as follows ;-. "In his late work on the Ancient Geography of India, General Cunningham quotes a passage from Pliny, in which the Malli are mentioned as this :-' Gentes: Calinge poximi mari, et supra Mandei Malli quorum mons Mallus .finisque ejus tractus est Ganges.' In another passage we have, (Ab iis (Palibothris ) in interiore situ monedes et Suari, quorum mons Mallus and putting the two passages together, General Cunningham 'thinks it highly probable that both names may be intended for the celebrated Mount, Mandar, to the south of Bhagalpur, which is fabled to have been used by the gods and demons at the churning of the ocean.' The Mandei General Cunningham iden-tifies' with the inhabitants of the Mahanadi river, which is the Mctnctda of Ptolemy.' ' The Malti or Malei would therefore be the same people as Ptolemy's Mandalm, who occupied the right bank of the Ganges to the south of Palibothra,' the Manclalm or Mandali having been a heady identified with the Monedes and the modern Munda Kols. 'Or,' adds General Cunningham, 'they may be the people of the Rajmahal hills who are called Maler, which would appear to be derived from the (Janarese Male and the Tamil Malei, a 'hill.' It would therefore be equivalent to the Hindu pahari or parbatiya a 'hillman." Putting this last suggestion aside for the present. it seems to me that there is some little confusion in the attempt to identify both the Monedes and the Malli with the Mundas. If the Mandei and the Matti are distinct nations-and it will be observed that both are mentioned in the same passage-the former rather than the latter would seem to correspond with the Monedes or Mundas. The Malli would then correspond rather to the Suari, quorum mons Mallus-the hills bounded by the Ganges at Hajmahal. They may therefore be the same as the Mals. In other words, the Mals-the words Maler and Malhar seem to be merely a plural form-may possibly be a branch of the great Sauriyan family to which the Rajmahal I aMri4s, the Oraons, and the Sabars all belong, and which Colonel Dalton wonld describe as Dravidian. Fifteen hundred or two thousand years ago this people may have occupied the whole of Western Bengal. Pressed by other tribes, they have long since been driven into corners, but not without, as it were, leaving traces. of their individuality behind. In Mal-bhumi (Manbhum) instead of 'the Country of the Wrestlers, ' as Dr. Hunter puts it, we seem to have the land of ' Mons Mallus' and the Mals. The Maldah district may also possibly owe its name to their having been settled there. As to the name, indeed it is quite possible that it means nothing more than highlanders; the word Malttts being simply the Indian vernacular for the Latin mons.

If a native were asked the name of

a hill in the present day, he would reply, as Pliny's informant probably replied years ago, that it was a ' hill;' and if asked the name of the¬ people who lived there, he would probably say they were' hillmen.'

"These Mals appear to have been driven eastwards and to have spread over the whole of Bengal, where they have become merged

in the mass of low-caste Hindus. This will account to some extent for what Colonel Dalton calls the Dravidian element in the com¬position of the Bengali race. Under the Hindu system the Mals, like other aboriginal tribes who came within the pale of Hinduising influences, appear to have formed one of the forty-five tribes of Chandals, the lowest or sweeper class among Hindus. Chandals are found in every district of Bengal, their aggregate number in the present day being over a million and a half. In Mymensingh, where we find 20,000 Mals, we have 123,000 Chandals. In the south-eastern districts they seem to have lost their name in t.he generic term of Chandals, but in the eastern districts they still retaiu it. In Birbhum and Bankura, in each of which districts there are about 9,000 Mals, there are not as many hundred Chandals. In Murshedabad there are 29,000 Mals against 22,000 who described themselves as Chandals. Most officers say the Mals are identically the same as the Chandals. Some say they are wrestlers, others attribute to them the same occupation as that of the Madaris or Sampheriyas, viz., that of snake-charmers. Others, again, say they are Musalmans, and identify them with Bediyas or Babajiyas; but in this explanation there seems to be some confusion, the two last tribes not being generally considered identical. The Babajiyas, though an itinerant tribe like the Bediyas, are employed, like the stationary Pasaris, in selling drugs. The returns, however, show that some of the Mals are Musalmans."

Internal structure

The most primitive specimens of the caste are met with in Bankura, where they have distinctly totemistic sections, and are divided into the following sub-castes :-Dhaiia, Gobra or Gura, Khera, Rajbansi, and Sanagantha. In Midnapur and Manbhum we find Dhunakata, Rajbansi, Sapurya or 8edya Mal, and Tunga; in Birbhum Khaturfa, Mallik, aud Rajbansi ; in the Santal Parganas Deswar, Magahiya, Rajbansi or Raja Mal, Rarhi Mal, and Sindura j while in Murshedabad the sub-castes are the same as in Bankuar, except that Dhalia is not known. The origin of these groups is extremely obscure, and I doubt whether any amount of inquiry would throw much light on the subject. Rajjbansi, for example, is the name adopted by a very large proportion of the Kochh tribe; but there is no reason to suppose that the Mals are Kochh, and they might easily have acquired the name Rajbansi in the same manner as the Kochh have done by identifying themselves with the lineage of a local Raja, who mayor may not have belonged to the same race. The simplest solution of the difficulty appears to be to assume that Mal is nothing more than a variant of Male, 'man,' the name by which the Male Paharias describe themselves. It is possible, again, that the Rajbansi Mals may be the same as Raja Mals whom Buchanan noticed among the Mal Paharias at the beginning of the century. The monkey¬catching Gobras bear the same name as one of the sub-castes of Bagdis j and Khera is not far removed from Khaira, whom some regard as a branch of the Doms. The SanagantM take their name from making schuis, the uprights through which weavers pass their thread. The Dhumikata Mars colleot resin (dlzuna) by tapping 8at trees; the Tunga sub-caste are cultivators; while the Sapurifl or Bedya Mars live by charming snakes, catohing monkeys, hunt.ing or conjuring, and roam about the country carrying with thorn small tents of coarse gunny-cloth. Although they catch snakes, Sapuria Mals bold the animal in the highest reverence, and will not kill it, or even pronounce its name, for which they use the synonym lata, , a creeper.'

Kinship with the Bediyas

The names of the last-mentioned group raise the probably insoluble question of the connexion of the Mals with the Bediyas.Dr. Wise treats both Mal and Samperia or Sapuria as subdivisions of the Bediya tribe; but it is equally possible that the Mal may be the parent group, and that the Bediyas may have separated from it by reason of their adhering to a wandering mode of life when the rest of the tribe had taken to comparatively settled pursuits. There certainly Beem to be reasons for suspecting some tolel'ably close affinity between the two groups. The Mals of Dacca, for instance, are called Ponkwah, from their dexterity in extraoting worms from the teeth, a characteristic accomplishment of the Bediyas. They repudiate the suggestion of kinship with the latter tribe, but it is said that many can recollect the time when relationship was readily admitted. At present, however, in spite of some survival of roving habits, peculiar physiognomy, and distinctive figures, Mals are with difficulty recognized. Many of them are small bankers (maMry'ans), never dealing in pedlar's wares, but advancing small sums, rarely exceeding' eight rupees, on good security. 'rhe 'rate of interest charged is usually about fifty per cent. per annum; but this demand, however exorbitant, is less than that exacted by many money-lenders in the towns. The Dacca Mals never keep snakes, and know nothing about the treatment of their bites. The women, however, pretend to a secret knowledge of simples and of wild plants. 'They are also employed for cupping, for relieving observe abdominal pains by friction, and for treating uterine diseases, but never for tattooing. The Mals of Eastern Bengal do not intermarry with Bediyas, and even within the limits of their own group a sharp distinction used to be observed between settled Mals and gipsy Mals ; so that if one of the former sought to marry a girl of the latter class, he was required to leave his home, give up his cultivation, and adopt a wandering life. This custom has gradually given way to a keener sense of the advantages of settled life, but its general disuse is said to be stili resented by the elders of the caste. Plausible as the conjecture may be which would trace some bond of kinship between the Bediyas and the Mals, the evidence bearing on the point is not precise enough to enable us to identify the Sapuriit Mals of Midnapur with the Samperiya Bediyas of Eastern Bengal. Snake-charming is an occupation likely enough to be adopted by any oaste of gipsy-like propensities, and there is no reason why both Mals and Bediyas should not have tallen to it independently. Further particulars will be found in the article Bediya ..

Exogamy

The Mens of Western and Central Bengal seem on The whole E to be the most typical representatives of the original Mal tribe. Among tbem the primitive rule of exogamy is in full force, and a man may not marry a woman wh0 belongs to the same totem group as himself. Prohibited degrees are reckoned by the standard formula calculated in the descending line to five generations on the father's and three on the mother's side. Outsiders belonging to higher castes may be admitted into the Mat community by giving a feast to tbe Mals of the neighbour¬hood and drinking water in which the headman of the village (manjhi) has dipped his toes. No instance of anyone undergoing this disagree-able ordeal bas been quoted to me, and such cases must be very rare.

Marriage

Girls may be married either as infants or after they have attained puberty, the tendency being towards the adoption of the former cu tom. The ceremony takes place just before daybreak in a sort of arbour made of mahua and sidha branches in tbe courtyard of the bride's house. After the bride has been carried seven times round the bridegroom the couple are made to sit side by side facing the east, and a vessel of water which has been blessed by a Brahman is poured over their heads after the manner of the Mundas and Oraons 1 Garlands of flowers are then exchanged, the clothes of the pair are knotted together, and if adult they retire into a separate room in order to consummate their union. On their reappearance they are greeted by the company as husband and wife. Polygamy is permitted, but most Mal' are too poor to maintain more than one wife. A widow may marry again,2 but no special ritual is in use, except among the Raja Mals of Birbbum, who exchange necklaces of beads or seeds of the tulsi (Ocynim sanctum and such marriages, which are called sanga, are effected by paying a small fee to the headman (khamid or manjhi and to the father of the widow. Divorce may be effected, with the sanction of the panchayat, on tbe ground of adultery by the wife, and divorced women may marry again in the same manner as widows.

Religion

Mals profess to have completely adopted Hinduism, and no vestiges of any more primitive religion can now e trace among tern. They seem to belong to whatever Hindu sect is popular in the locality where they are settled; and in different districts they describe themselves as Vaishnavas, Saivas, or Saktas, as the case may be. The snake goddess Manasa is believed to be their special patroness, and is worshipped by them in much the same fashion as by the Bagdis. Sacrifices of rice, sweetmeats, and dried rice are also offered by the heads of families to the tutelary goddess of each village, who bears the name of the village itself with the termmation sini I According to some accounts Jalma, the goddess of water, must first be worshipped With gifts of flowers at a neighbouring tank, and water drawn From Lhi Lank must be used in the marriage in addition to water blessed by a Brahman. 3 This is the general rule, but Lha Rajbansi Mals of Midnapur have recently abandoned widow.marriage. added; 80 that the goddess of the village Pathara would be called Patharasini. In most districts they have not yet attained to the dignity of employing Brahmans, but elders of the caste or headmen of villages serve them as priests (lc1uimtd) . In the Santal Pal'ganas, however, the Brahmans of the Let sub-caste of Bagdis officiate also for the Raja Mals.

Disposal of the dead

The dead are burned, usually at the side of a stream, into which the ashes are thrown. A meagre imitation~ ceremony is performed on the eleventh day after death in ordinary oases, and on the third day for those who have died a violent death. On the night of the Kali Puja in Kartik (October-November) dried jute stems are lighted in honour of departed ancestors, and some even say that this is done to show their spirits the road to heaven. Libations of water are offered on the last day of Chait. Female children are buried mouth downwards, and the bodies of very poor persons are often buried with the head to the north in the bed of a river.

Occupation and social status

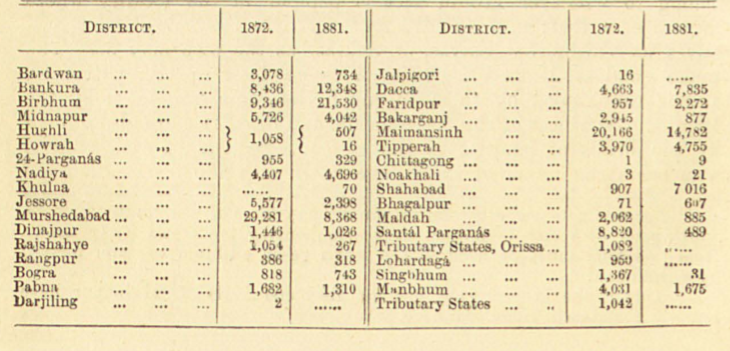

Agriculture is supposed to be the original profession of the caste, and most Mals, except those of distinctly gipsy habits, are now engaged in cultivation as occupancy or non-occupancy raiyats and landle5s day-labourers. None appear to have risen to the higher rank of zamindar or tenure-holder, except in Bankura, where one sardar ghatwal, one sadial 56 tabidars and 35 chakran cI.aukidrirs are Mals. In ManbhuID, on the other hand, which some believe to 'be the original home of the caste, no MeHs are found in possession of these ancient tenures, though some are employed as ordinary village chaukidars. The women of the caste and some of the men often make a livelihood by fishing-a fact which accounts for their bearing the title of Machhua. Their social status is very low, and is clearly defined by the fact that Bagdis and Koras will not take water from their hands, while they will take water and sweetmeats not only from those castes, but also from Baur'is. Mals pride themselves on abstaining from beef and pork, but eat fowls, all kinds of fish, field-rats, and the flesh of the gosarnp (Lacerta godica). The Raja. Mals, however, do not touch lowls. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Mals in Itl72 and 1881 :¬