Mali, Malakar

Contents |

Mali, Malakar

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Tradition of origin

A caste employed in making garlands and providing flowers for the service of Hindu temples. In Bengal the caste is included among the Nava-Sakha, and its members profess to trace their descent from the garland maker attached to the household of Raja Kansa of Mathura, who, when met by Krishna, was asked for a chaplet of Howers and at once gave it. On being told to fasten it with a string, he, for want of any other, took off his sacred thread and tied it, on which Krishna most ungenerously rebuked him for his simplicity in parting with his paita, and announced that for the future his caste would be ranked among the Sudras. Like others of the bigber castes, the Malakars claim to have originally come from Mathura in the reign of Jahangir. They are few in number, but in every Hindu village there is at least one representative, who provides daily offerings of Howers for the temples and marriage tiaras for the village maidens.

Internal structure

They are divided into two main groups-the Phulkata•Mali, who make ornaments, toys, etc., from the pith of the sola, and the Dokime Mal i, who keep shops. The former group is again broken up into Rarhi, Barendra, and Athgharia, the last of whom are supposed to be descended from eight families outcasted for some cause now forgotten. Their sections, which are shown in Appendix I, belong to the ordinary Brahmanical series, and are supplemented by the regular rules regarding prohibited degrees. In Dacca, according to Dr. Wise, the cafe has only one gotra .Alamyan, and two dals , or unions, between which there is no real difference. If, however, a member of one union marries into a family belonging to the other, the marriage feast will be more expensive than if he took a bride from his own, as he must invite the members of both dais to the ceremony. The bridal dresses must be made of red silk brought from Murshedabad, as cotton cloth is prohibited. The bride is always carried in a palki or palanquin, while the bridegroom rides on a pony or in a Sedan chair. Malis marry their daughters as infants, forbid widows to marry again, and do not recognize divorce. 1£ a wife is proved to be unfaithful, she is turned out of the caste, and her husband performs a snrt of penance to purify himself from the slur of having associated with her.

Religion

The Malabirs are all Vaishnavas by creed, and it is said that none of them worship Siva. A Gosain is their guru, while their Brahman is common to them and to the Nava-Sakha. "

Occupation

A Mali will not cultivate with his own hands, and never work as a kitchen-gardener, the gardeners of Bengal being generally Ohandals and Uriyas. Many Malis, however, hold land.as occupancy raiyats, which they cultivate by means of hired labourers. In Dacca members of the caste keep bhops for piece-goods, practise medicine, act as vaccinators, and take service in temples. Their principal occupations, however, are making wreaths, fabricating artifical chaplets and toys from the pith of the sola (Hedysarum lagena1ium ). The garland placed every morning before idols are collected and arranged by Malaklirs, who nevertheless refuse to paint figures, this being the profession of the Ganak and Rangrez. All the tinsel decorations put on the images and their carriages are designed by Malakars. At marriages their services are indispensable, for they prepare the crowns (Mukutal worn by the bridal pair. Morover, no bride would consicler the attire complete unless her hair was adorned with a Khopaj ura, or ornament for the hair-knot, made with leaves of the jack-tree mL""\:ed with white Bela blossoms, while at one side of it they place a rose or some other bright flower. For the bouquet delivered on the bridal morning the Malakar expects to be paid a rupee.

" The profession of a Malakir requires a considerable knowledge of flowers, for some are forbidden to be used in religious services and others can only be exhibited before the shrines of the deities to whom they belong. Thus the ' DhatUra' is sacred to Siva; the 'Aparajita' (Clit01'ia ternatea) to Kali; the 'Bakas' (Justicia odhatoda) to Saraswati; aud the 'A.oka' (Jonesia asoca) to Sashthi. The 'Java' (Hibi.~ct6s ?"osa Sinensis) or Ohina rose is of most nnlucky omen, and can only be presented to Kali, but not to other idols, nor employed at weddings. "Strong scented blossoms are selected for religious offerings, and these in Eengal are the 'Champa.' (Mich elia Cftampnca) , 'OhameH' (Jasrnimtm gran (l1jlont7n.) , 'Jul' (Jasminum auricu¬ latllm) , 'Bela' (Jasminum Zambac), ' Gandhraj , (Garclmia florida), and the' Harsingar' (Nyctanthes arbol" tristis). " chaplets offered to idols must be tied with the dried fibres of the plantain stem, not with string, and if picked and arranged by one not a Malakar they are unclean. From sixteen to twenty-four anllas a month ru:e received by the garland-maker for providing a daily supply of flowers to a temple; but, as with everything else, the price Of bouquets has greatly risen, and a rupee ouly procures about haH the quantity it formerly did. "One of the chief occupations of this caste is inoculating for small-pox and treating individuals attacked by any eruptive fever. Hiudus believe that SitaLi, the goddess of small-pox, is one of seven sisters, who are designated Motiya, Matariya, Pakauriya, Ma urika, OhamllIiya, Khudwa, and Pansa. rrhe first four are varieties of small-pox, the names refelriug to the form, size, and COIOUT of the pustules; the fifth is Variola maligna; the sixth is measles ; and the seventh is water-pox. Every MalaMr keeps images of one or more of these goddesses, and on the first of chait (March 15th) a festival is held, and the Milakars superintend the details. It is popularly ' called 'Malibagh,' from the garden where the service is performed, and thither Hindus and Muhammadans repair with offerings of clotted milk, cocoanuts, and plantains in the hope of propitiating the dreaded sisters.

" When small-pox rages, the Malakars are busiest. As soon as the nature of the disease is determined, the Kablr3j retires and a Malakar is summoned. His first act is to forbid the introduction of meat, fish, and all food requiring oil or spices for its preparation. He then ties a lock of hair:, a cowrie-shell, a piece of turmeric, and an article of gold on the right wrist of the patient. The sick person is then laid on the 'Majh-patta,' the young and unexpanded leaf of the plantain tree, and milk is prescribed as the sole article of food. He is fanned with a branch of the sacred nZ1n, and anyone entering the chamber is sprinkled with water. Should the fever become aggravated and delirium ensue, or if a child cries much and sleeps little, the Mali performs the Mata puja. This consists in bathing the image of the goddess causing the disease and giving a draught of the water to drink. To relieve the irritation of the skin, peasemeal, turmeric, flour, or shell-sawdust is sprinkled over the body. " If the eruption be copious, a piece of new cloth in the figure of eight is wapped round the chest and shoulders. On the night between the seventh and eighth days of the eruption the Mali has much to do. He places a waterpot in the sick room, and puts on it alwa. rice, a cocoanut, sugar, plantains, a yellow rag, flowers, and a few in leaves. Having mumbled several mantras, he recites the kissa, or tale, of the particular goddes, which often occupies six hours. , 'When the pustules are mature, the Mali dips a thorn of the karaunda (Gm'is8fI) in til oil, and punctures each one. The body i then anointed with oil, and cooling fruits given. When the scabs (dewli) have peeled off, another ceremonial, called 'Godam,' is gone through. All the offerings on the waterpot are rolled in a cloth and fastened round the waist of the patient. These offerings are the perquisite of the Mali, who also receives a fee. "These minute, and to our ideas absurd, proceedings are practised by the Hindus and Muhammadans: including the bigote.d l! arazi, whenever small-pox or other eruptive fever attacks their families. Government vacinators earn a considerable sum yearly by executing the Sitala worship, and when a child is vaccinated a portion of the service is performed."

Social status

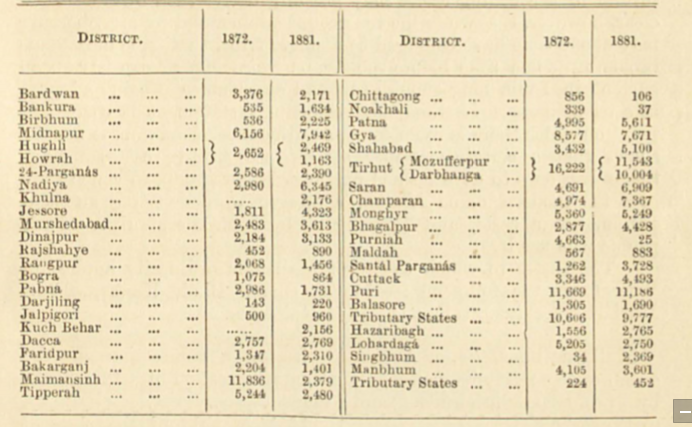

The Malis of Behar hold a respectable position among the castes of that province. They rank with Kumbars, Koiris, and Kahars, and Brahmans will take water from their hands. The main difference between them and the Bengal Malis is that they practice widow-marriage, and do not take all extreme view of the necessity of getting their.' daughters married as infants. With this exception, the account given above of the Bengal Malis applies for the most part to the Behar members of the caste. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Malis in 1872 and 1881 :¬