Malo, Bankura

Contents |

Malo

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Internal structure

Malo-Patni, a Dravidian boating and fishing caste, supposed by Buchanan to have come from Western Indian. This opinion, however, IS an unsupported by any evidence beyond a resemblance of name, which may be either wholly accidental or may have arisen from the tribal name Malo being confounded with the Arabic word Mallah, 'a boatman.' Dr. Wise considers the three fi 'her castes-the Kaibartta, Malo, and Tiyar-to be "undoubtedly representatives of the pre-historic dwellers in the Gangetic delta. As a rule they are short and squat, of a dark-brown colour, often verging upon black. Although Hindus by creed, they are fond of showy garments, of earrings, and of long hail', which is either allowed to hang dowl! in glossy curls on their shoulders or fastenen in a knot at the back of the head. The whiskers and moustaches are thin and scrubby, the lips often thick and prominent, the nose short with the nostrils expanded. The physiognomy indicates good temper', sensuality, and melancholy rather than intelligence and shrewdness." The sections of the Malos, shown in Appendix I, seem on the whole to bear out the view that they are the remnant of a distinct aboriginal tribe, and Dot merely an occupational group. These sections are peculiar to the Malos, and do not appeal' to have been borrowed from any other caste. r am unable to analyse them completely, but r venture the conjecture that some of them are totemistic, the totems being the rivers, which the Malos regularly worship. There are no sub-castes. The Rajbansi, which some authorities are disposed to regard as a sub-caste of the Malo, are clearly Kochh, who have taken to fishing, while the Katar or Bepari Malo, who deal in, but do not catch, fish, and derive their name from their practice of cutting up their wares and selling them by weight, are Muhammadans in no way connected with the Malo caste.

Marriage

The rule of exogamy is in full force among the Malo. A man may not marry a woman of his own section or of the section to which his mother belongs. For the rest, marriage is regulated by counting degrees down to seven generations in the descending line. Females are married as infants. A price is paid for the bride, which of late years has risen to the large sum of Rs. 100. The ceremony is of the orthodox type, the giving of the bride and the bridegroom's formal acceptance of the gift being the essential and binding portion of the rite. Polygamy is permitted in theory, and a man may marry two sisters, provided that he takes the eldest first. In practice, however, I understand it is unusual to marry a second wife unless the first proves barren. Widows may not marry again, nor is divorce permitted. A woman taken in adultery is abandoned by her husband and turned out or the caste.

Religion

Malos as a rule belong to the Vaisbnava sect. 'Their purohit is a Patit Brahman, and their gll1'lt a Gosain. Special reverence is paid by them to the great rivers on which they live, and these, together with their boats and nets, have tbeir' regular seasons of worship. Khala-Kumari is worshipped in Sravan (July-August), offerings are made to BuraBuri in fulfilment of vows, and lights are launched on the water in honour of Khwaja Khizr.

Disposal of the dead

The dead are usually burned on the bank of a river, and the ashes cast into the water. Sraddh is performed on t e thirsty first day after death then once a month for a year, and again on the first anniversary of the death. Usually, however, the monthly sraddhs are lumped together towards the close of the year. In the case of persons who die a violent deatb, the first s1'licldit is performed on the fourth day, and a final sraddh on the thirty first day.

Social status

Although the social rank of the Malos is low, and Brahmans will not take water from their hands, the Napit and Dhoba usually work for them. 'T'hey are on good terms with the Tiyar and Kaibartta, and members of the three castes will even smoke together. The Malo, however, says Dr. Wise, "is the lowest in rank, while the Kaiblibrtta and Tiyar still dispute about their relative positions. The Kaibartta, again, is more thoroughly Hinduised than either of the other two. A ridiculous distinction is always oited in proof of the inferior rank of the Malo. The Kaibartta and Tiyar in netting always pass the nettin)! needle from above downwards, working from left to right; while the Malo passes it nom below upwards, forming his meshes nom right to left. It is remarkable that the same difference is adduced by the Behar fisherman as a proof of the degraded rank of the Banpar." The only titles met with among Malos are Manjhi, Patra, and Bepari, while among other fisher castes no honorary distinctions exist. Under the Muhamadan Government they served as boatmen, chaprasls, mace•bearers (asabardar), and staff-bearers (sonte-bardar) in processions. They were also employed in conveying treasure nom Dacca to Murshedabad, while a tradition still survives that early in this century two of their number became great favourites with Nawab Nasrat Jang, who presented them with golden spinning wheels for their wives' use. The Malos therefore extol the golden age that has passed, and inveigh against the equality and degeneracy of the present.

Occupation

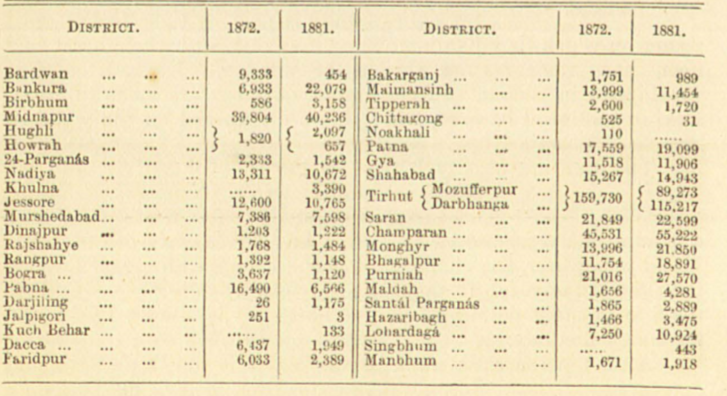

Malos generally use a shorter Jalka boat than the Tiyars, but when they fish with the long Uthar net they fasten two boats stem to stern. Like the Kaibartta, the Malo is often a cultivator, and in Bhowal he has been obliged by changes in the course and depth of the rivers to relinquish his caste trade. Malos manufacture twine, but not rope, and traffic in grain, while those who have saved a little money keep grocer's shops or become fishmongers. Malo women sell fish in the bazors, but ill some places this practice is considered derogatory to their gentility and is prohibited. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Malos in 1872 and 1881 :¬