Middle class: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Its size

As of 2024

Chandrima Banerjee, March 26, 2025: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, March 26, 2025: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, March 26, 2025: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, March 26, 2025: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, March 26, 2025: The Times of India

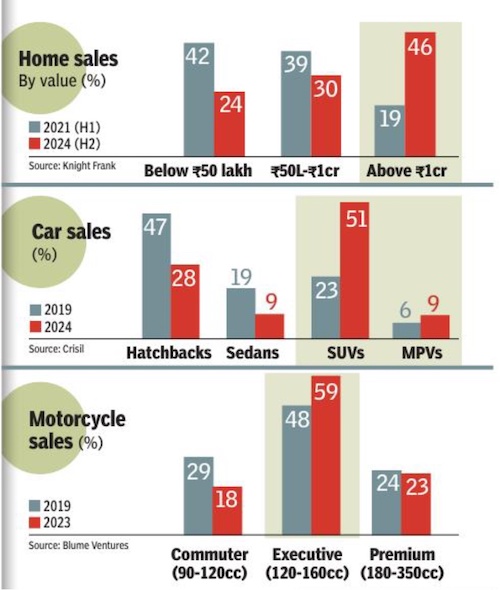

Some 10% of the richest Indians (over 14 crore) are apparently driving actual money-making consumption. You know, paying for the things they want — when they want it. The next 23% (or 32 crore) are “heavy consumers and reluctant payers”. And the remaining 67% have absolutely no extra money to spend on anything beyond the basics — sometimes, not even that.

Usually, numbers like these don’t move the needle. It is a country of 1.4 billion (140cr) people, one might think, and explain it away with the brute force of large numbers. And one can always find “problems” with how the numbers were even arrived at — the sample was too small, the sample was not representative, the non-profit that did the survey had a point to make, the govt body which came up with the numbers changed its methodology, and so on.

The thing is, these numbers came from a venture capital firm, Blume Ventures. People who have to figure out actual spending capacity as closely as possible because their business model depends on it.

In their analysis of Indian consumers, they say that some 1 billion Indians have no extra money to spend. And that some 300 million people are those slowly opening up their wallets because they can, sometimes — they make up the middle aspirational consuming class.

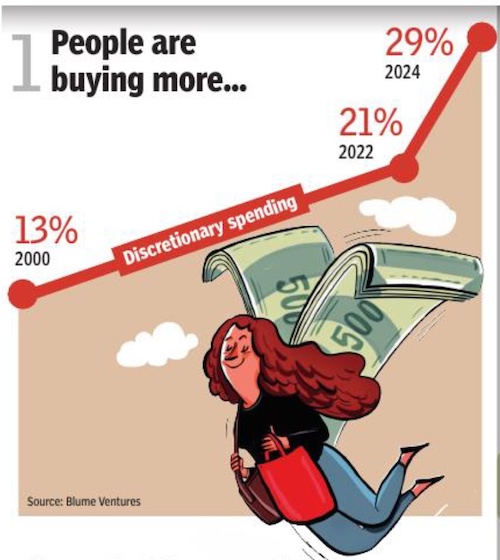

1 People are buying more… Consumption is by no means down — 60% of India’s GDP comes from private consumption. And close to a third of it is discretionary spending (or non-essential, like on entertainment or dining out or vacations). Is most of it by the richest alone? The Blume report says that at least one-third of the discretionary spending is by the aspirational middle class.

But it also depends on how we understand the middle class. It has always been difficult to define its two ends in India. Blume’s consumer analysis, for instance, considers the ‘middle’ consuming class to have an average income of 2.6 lakh and the ‘rich’ consuming class about 13 lakh. However, the government exempts income up to 4 lakh from taxes. It considers a household income of 8 lakh as being low enough for the economically weaker section category. And, with its latest Budget, it has made provisions so that anyone with income up to 12.75 lakh doesn’t have to pay taxes. So, the ‘richest’ consumers might still be ‘middle class’ in some analysis.

2 …And they’re ditching cheaper options

Home prices are expected to climb faster than consumer inflation this year, a recent Reuters poll of housing experts said. The NHB index shows that under-construction property prices are usually higher than assessment prices — but this gap has been getting wider since mid-2022 in many cities. Knight Frank reports on Indian real estate over the years also show how this has changed. Besides the “premium” turn that real estate has taken, the latest report points out that close to 40% of the unsold inventory of houses in these cities costs less than 50 lakh. Because sales are dropping. Likewise, for cars, prices have risen 7-9% annually over the past five years and, like most things people are buying, the share of “premium” vehicles has been shooting up.

3 But incomes have stagnated

The latest Economic Survey said that “corporate profitability soared to a 15-year peak” in the last financial year, but “while profits surged, wages lagged”. It flagged this as a risk, saying, “To secure long-term stability, a fair and reasonable distribution of income between capital and labour is imperative.”

Data from the International Labour Organisation show that the average hourly earnings of an Indian worker are the fifth lowest in the world in PPP terms. Even if it’s someone with an advanced degree or doing a skilled job, they’re still paid the world’s seventh-lowest wages. It is not a contest most middle class people always expect to win — the one between ever-soaring prices and earnings and savings. But what they have to spend their money on does determine how things turn out. A decade ago, the largest share of urban non-food expenses was on education, the government’s consumption survey shows. Now, it’s on transportation, just getting to places.

4 So, middle class income ≠ middle class consumption?

The Indian middle class in terms of income and in terms of consumption are not the same anymore. What is certain is that it is consuming more and better, but the pace and distribution of that more-and-better are far too varied.

Which means it’s possible for a household that is value-conscious while buying groceries to splurge on a car. Or a salaried professional who looks for bargains when hiring an electrician is fine with planning an extravagant vacation. At least part of it is because of debt. People are saving less, borrowing more. And the scale of change is striking.

If you think about it, is it likely — not right or wrong, just likely — that previous generations of middle class Indians would have thought of paying 1.45-crore interest on an 80-lakh loan (assuming a 20-lakh down payment) as a practical way to fund their dream home? Probably not. But it made sense to a lot of people over the past few years because the hope was that their incomes and wealth would keep growing as the economy kept growing.

Till that consistent promise of upward mobility holds up, the middle class will keep growing in numbers but may not grow quite as much in terms of sustainable spending capacity.

Points of view

India has no middle class

‘Those Earning Over $10 A Day Constitute The Top 5%’

Rukmini Shrinivasan

Times of India 2005 figures

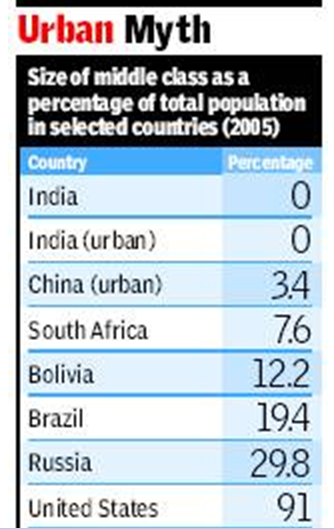

New Delhi: Could the Great Indian Middle Class be the Great Indian Mythical Class? A proposed new international definition of what constitutes the middle class in a developing country has thrown up a startling conclusion by global standards, India has no middle class.

Noted economist Nancy Birdsall, president of the Center for Global Development, has proposed a new definition of the middle class for developing countries in a forthcoming World Bank publication, Equity in a Globalizing World. Birdsall defines the middle class in the developing world to include people with an income above $10 day, but excluding the top 5% of that country. By this definition, India even urban India alone has no middle class; everyone at over $10 a day is in the top 5% of the country.

This is a combination both of the depth of India’s poverty and its inequality. China had no middle class in 1990, but by 2005, had a small urban middle class (3% of the population). South Africa (7%), Russia (30%) and Brazil (19%) all had sizable middle classes in 2005.

While many economists have in the past as well attempted to define the middle class, Birdsall puts into monetary terms the broader concept of what a middle class really is, as opposed to merely counting the middle third of a country. In socio-political terms, the middle class is traditionally that segment of society with a degree of economic security that allows it to uphold the rule of law, invest and desire stability. They do not, unlike those defined as rich, depend on inheritances or other non-productive sources of income.

Birdsall argues that while the equivalent of $10 per day in 2005 as a lower limit is on the low side by the standards of industrialized countries, somewhere around $10 a day per person household members are able to care about and save for the future and to have aspirations for a better life for themselves as well as their children because they feel reasonably secure economically. OECD countries define their poverty lines as 50% of median income which works out in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms to about $30 day. In US the poverty line for a single individual in 2008 was $29 per day and for each individual in a four-person household was about $14 per day.

However, people in developing countries living on even $10 a day still have extremely low social indicators. Economist Lant Pritchett has shown that infant mortality of households in the richest quintile in Bolivia was 32 and Ghana 58 per 1,000. Fewer than 25% of people in the richest quintile in India complete 9 grades of school, Pritchett showed. “An upper limit of the 95th percentile, while on the high side, is just about sufficient to exclude the countrys richest,” Birdsall adds.