Moeen Faruqi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Moeen Faruqi

Moeen Faruqi

POP ART: Judging a book by its cover

By Aasim Akhtar

The critic today is confronted with a strange dilemma: that of meaning. Do all works of art possess certain significance for us that goes beyond the surface value of the canvas? Or, to put it another way, do all objects of art have a symbolic purpose? Is a drawing or a painting valid only if it can be analysed, traced to its origins, and thus understood?

Some artists have reacted defiantly to attempts to strangle art in a narrow vise. There are critics who vehemently deny a necessity to explain the meaning of the image. We are informed by Archibald MacLeish that a poem should not mean but be. Aesthetic purity remains the essence of the object; but then, paradoxically, it may cease to have meaning for the reader or the beholder.

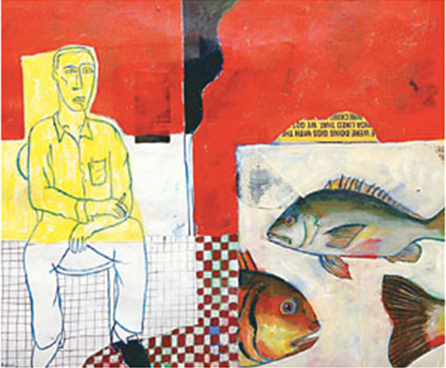

The paintings and drawings of Moeen Faruqi, comprising acrylics on paper and canvas, and a sculpture installation on show at Rohtas 2 in Lahore, belong to this genre, which defies the scope of interpretation. On the face of things, his work seems remarkably naïve and picturesque, “memories of something once known and since forgotten, like childhood or paradise”. It lacks any sense of dogma; yet it is a statement of fact. Faruqi’s is a strange, pictographic language. Strange because his images are so familiar, so bold, so insistent in their rhythmic patterns. What is one to make of a fish that remains essentially a fish, or for that matter of bottles and rugs, and cats and ducks? There is no heroic endeavour, no epic grandeur about these images, no satirical punch line; but there is poetry, and there is magic.

The overall view, the multiple perspective of these pictures and the hot luscious colours create a sensation of unease which some describe as erotic. This is a world peopled as much with tables and chairs and overgrown plants as with human beings who remain, on the whole, submissive and incidental. A hothouse world of the imagination, in a sense akin to the jungles of Douanier Rousseau; except that what we experience here is not wild animals and sleeping gypsies but sofa sets and potted plants. This is a world of magical enchantment. Whereas in Alice in Wonderland, it is the white rabbit and strange, hybrid creatures who speak out their thoughts and feelings, here it is the everyday objects of green bottles and teacups and decorated chairs that seem to come alive, to vibrate with perceptions and emotions.

In Faruqi’s world of make-believe, the inanimate become animate and converse with each other. We might recall the comments of Maurice Denis, speaking about the Nabis in Paris in 1895: “They preferred expression through decorative quality, through harmony of forms and colours; through the application of pigments…They believed that for every emotion, for every human thought, there existed a plastic and decorative equivalent”.

Invariably it is the magical world of the room interior that marks Faruqi’s playground. As he develops his personal idiom, the images in this interior begin to change over the years. Like a child’s toys, they are discarded and give place to other objects of interest and amusement.

Pictures emerge into family portraits; then the cats and ducks and fish, the chequered tablecloth, the flowers, etc. With increasing recurrence, in recent years it has been the cat and the fish, which have an obsessive and magnetic quality for him. These are products of a fertile imagination at work, making the familiar come intensely alive so that they project feelings and moods that we share. His art permits, even encourages, special intimacies of reading: his images dwell, not in the particularities of place and telling, but in the amplitudes of connection.

The world of Faruqi, while it lays no claim to such principles of aesthetics, deals with analogies. Both his drawings as well as the object of his oils are metaphors. They express a mood, a feeling of happiness or joy or fatigue or sadness, a time of day or evening or night, by referring to it through means of an object; or through the shape of the object, its colour, and more recently, through its texture. All this may seem irrelevant, except that it helps us to understand why these objects are assembled together, and how they coalesce in his composition.

In his art — which is sophisticated in its interplay of the serious and the ludic; radically plural in its sources and methods — Faruqi invents, and keeps reinventing, a mutable self that has been redeemed from all dogmas of self-representation. To approach his art is to understand its kaleidoscopic powers of shape-shifting, its fluent tactical ability to reorient itself towards an unfolding variety of contexts while pursuing the deep programming of its inquiries and obsessions. Images accost us; we greet them with the stories that we know, and wait to hear the fables they have brought with them. Are they plumed satyrs or courteous drunks, centaurs in frontal view or actors romping about in a farce?

Faruqi does not proceed by linear, obvious means here; wandering through the dense vegetation and tricky contours of the urban topography, he abandons the cartographer’s mad desire to control the world through an overworked map. Instead, he reclaims the narrative through trace and gesture, emblem and allusion. The grand dynamics of a male-dominated narrative yield, in Faruqi’s handling, to the narration of details from a woman’s point of view. The monumental and public is given up in favour of the miniature and intimate; his narratives are elliptical, syncopated, allusive and elusive.

In this suite of works, Faruqi steps out of his gender identity, symbolically, to embrace what it might feel like to be a woman. In his account, she talks to the animals of the forest that is both in her mind and around her. And sometimes, she vanishes, leaving us with the ‘spectrality’ of dead words and metaphors that are being stoked to life again. She disappears, leaving us with discomfiting auguries and unsettling performances for company. What is this golden quern, grinding the grain of our days to powder, dismissing our hopes and desires as chaff? Then the female reappears, disturbing in her agitation, sensuous in her migratory charting of inside and outside, then and now, home and away. And her gestures baffle us. Will she break these jewelled rings in her grinding wheel? And why does she flash her spine at us: shall we count the years leading up to disaster on her vertebrae?

The protagonist of Faruqi’s suite of mixed-media works is a female figure; part waif and part athlete, part naiad and part lunatic, she stands at the receiving end of a brutal fate. But she is never a victim; on the contrary, she grapples heroically both with collective history and personal destiny. The labouring female body has fascinated Faruqi; but unlike his forebears, he never renders his subject in idealised or romanticised fashion. In his handling, the female body is the bearer, not only of fortitude, but also of menace: by her sheer presence, by her awkward gestures and ‘uncontainable quixotry’, she disturbs the settled order of the patriarchal universe.

In the polymorphous world of Faruqi’s dreams, the females figure themselves sexually at the centre of a series of family connections, bizarrely recalling the role of the siren. Faruqi is particularly astute in showing the queer tension and pleasure in the most regular relations. The networks of his images extend from this family intensity and ensuing family ruptures out to the sheer eroticism of the scenes. Faruqi’s interest is in charting a response, translating emotion and sensation into images and cinematic narrative. Here, he takes us into the intimate confines of his characters’ lives — charting domestic rituals, bodily acts, the affect and failures of family exchanges — while indicating all that remains opaque, untapped, for the characters themselves and the viewers.

The chill and grit of the scene in ‘Voyeurs in our Midst’, for instance, as it renders physical the hostility between the characters, losing the last remnants of their love, are written over, ironically, by the unlikely tenderness of the ménage a trois. Where the ‘Untitled Works’ in collage and acrylics on paper are already a jigsaw in pieces — offering scenes of a marriage — it is as if ‘Shirtless Endgame’ shakes up the pieces once more in a new kaleidoscopic pattern. Faruqi here and elsewhere confounds expectation; in one sense his images are increasingly familiar, yet within a series of templates he continues to produce a vision of human interaction and affect which is aptly unexpected and — in emotional terms at least — experimental.

Taking a narcissistic character that resists communication and confession, Faruqi risks alienating his viewer. But for me, over time, the brilliance of his oeuvre lies precisely in what is unspoken: in its gradual substitution of fantasy for reality, in its cool ability to continue its trajectory towards mental delusion and death. On this perilous route, Faruqi approaches a range of emotions too brute, too highly coloured, too cloying, for some. But for others, with more indulgence, his moves will seem bold and intense, and prescient in presenting the isolation and unreality, and the unspeakable anguish, of relations.

Clockwise top: Strange Animals; Shirtless Endgame; Talking to the Walls; Chamber Dialogue; Untitled No.1

Moeen Faruqi

Riddled with chaos

By Salwat Ali

It is Moeen Faruqi’s blazing palette with the attention grabbing power of a neon sign and his chilling portrayal of estranged protagonists locked in a love hate relationship that identifies his art in the viewer’s mind. His current show at Canvas, Karachi, titled “Analogous Minds” reaffirms his pronounced signature as he continues to explore the disquieting isolation of couples who are together yet alone.

Moeen examines the human condition within the confines of an urban jungle and his particular brand of introspective imagery harks back to the realist art of the inter war and post World War years. Late 19th century exploration of the irrational and the fantastic and the growing interest in naïve and primitive modes of expression in art culminated during World War 1 in the form of Dada, which in the mid 1920s developed into surrealism. The Dadaists felt that reason and logic had led to the disaster of World War, and the only way to salvation was through political anarchy, the natural emotions, the intuitive and the irrational.

The mute anarchism reflected in Moeen Faruqi’s subjects speaks of spiritual poverty and identity crisis of this age. He paints the psychological trauma of life in a metropolis riddled with cultural, economic and political chaos. His garish ‘in the face’ chromatics are silent screams of protest against a manipulative world order where the inhabitants are forced to retract within themselves as a defensive gesture.

As prisoners of self their interaction with fellow beings is clouded with cynicism, reserve and distrust. To convey these moods and impressions he relies largely on the awkward, wooden body language of his subjects and insinuating or detached blank stares which seem to be hiding a thousand stories. Simmering, seething, cold or detached his characters are an island unto themselves but strong colouration and a sharp jagged brushwork of blended tonalities peculiar to his previous exhibition titled ‘New Realism’ cast a painterly impression over the works.

In the current Canvas show only some paintings like ‘First Date,’ ‘Ernesto in Love,’ and ‘Encore’ conformed to this attitude and these were by far the most interesting. Others like ‘The Waiting Room,’ and ‘Jazz Effect No 2,’ are non figurative and carry a new angular vocabulary of planes, diagonals and curlicues evoking the geometry of Leger and Mondrian. This experiment is followed by a small collection of collage grafted paintings in which torn newspaper and magazine pictures are incorporated into the painted surface. Of these, ‘First Date’ and ‘Found You’ only, have engagement value.

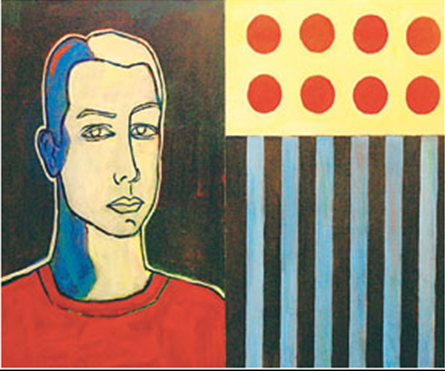

A considerable number of art works in the exhibition are part of his Analogous series where the artist has played with fields of flat colour juxtaposed with circular discs and vertical bars. Moeen’s new playground of geometric symbols and anemic figures has no cerebral twist or design value. If he is side tracking to have a bit of fun, then the sooner he gets over this dalliance the better. These paintings appear bland and banal when compared to the pungent surreal and arcane imagery so peculiar to his oeuvre. One hopes this is a brief interlude only. Moeen is a serious painter capable of intense, provocative work.

The Canvas exhibition is uneven and it shows Moeen experimenting with new approaches like collage and geometric symbols to add spice to his work which is a healthy sign of growth. However for a conceptual painter of his caliber, it is not just cosmetic changes but meaningful intellectual developments as well that carry the work forward.