Muzaffarpur District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Muzaffarpur District

Physical aspects

District in the Patna Division of Bengal, lying between 25° 29' and 26° 53' N. and 84° 53' and 85° 50' E., with an area of 3,035 ^ square miles. It is bounded on the north by the State of Nepal; on the east by Darbhanga District; on the south The area shown in the Census Report of 1901 is 3,004 square miles. The figures in the text are those ascertained in the recent survey operations, by the Ganges, which divides it from Patna ; and on the west by Champaran and the river Gandak, which separates it from Saran.

The District is an alluvial plain, intersected with streams and for the most part well watered. It is divided by the Baghmati and Burhl or Little Gandak rivers into three distinct tracts. The ysica country south of the latter is relatively high ; but there are slight depressions in places, especially towards the south-east, where there are some lakes, the largest of which is the Tal Baraila. The dodb between the Little Gandak and the Baghmati is the lowest portion of the District, and is liable to frequent inundations. Here too the continual shifting of the rivers has left a large number of semi-circular lakes. The area north of the Baghmati running up to the borders of Nepal is a low-lying marshy plain, traversed at intervals by ridges of higher ground. Of the two boundary streams, the Ganges requires no remark.

The other, the Great Gandak, which joins the Ganges opposite Patna, has no tributaries in this part of its course ; in fact, the drainage sets away from it, and the country is protected from inundation by artificial embankments. The lowest discharge of water into the Ganges towards the end of March amounts to 10,391 cubic feet per second ; the highest recorded flood volume is 266,000 cubic feet per second. The river is nowhere fordable ; it is full of rapids and whirlpools, and is navigable with difficulty. The principal rivers which intersect the District are the Little Gandak, the Baghmati, the Lakhandai, and the Baya.

The Little Gandak (also known as Harha, Sikrana, Burhi Gandak, or the Muzaffar- pur river) crosses the boundary from Champaran, 20 miles north-west of Muzaffarpur town, and flows in a south-easterly direction till it leaves the District near Pusa, 20 miles to the south-east; it ultimately falls into the Ganges opposite Monghyr. The Baghmati, which rises near Katmandu in Nepal, enters the District 2 miles north of Maniari Ghat, and after flowing in a more or less irregular southerly course for some 30 miles, strikes off in a south-easterly direction almost parallel to the Little Gandak, and crossing the District, leaves it near Hatha, 20 miles east of Muzaffarpur. Being a hill stream and flowing on a ridge, it rises very quickly after heavy rains and sometimes causes much damage by overflowing its banks. A portion of the country north of Muzaffar- pur town is protected by the TurkI embankment.

In the dry season the Baghmati is fordable and in some places is not more than knee deep. Its tributaries are numerous : the Adhwara or Little Baghmati, Lai Bakya, Bhurengi, Lakhandai, Dhaus, and Jhlm. Both the Bagh- mati and Little Gandak are very liable to change their courses. The Lakhandai enters the District from Nepal near Itharwa (18 miles north of Sitamarhi). It is a small stream until it has been joined by the Sauran and Baslad. Flowing south it passes through Sitamarhi, where it is crossed by a fine bridge, and then continuing in a south-easterly direction, joins the Baghmati 7 or 8 miles south of the Darbhanga- Muzaffarpur road, which is carried over it by an iron-girder bridge. The stream rises and falls very quickly, and its current is rapid. The Baya issues out of the Gandak near Sahibganj (34 miles north-west of Muzaffarpur town), and flows in a south-easterly direction, leaving the District at Bajitpur 30 miles south of Muzaffarpur town. The head of the stream is apt to silt up, but is at present open. The Baya is largely fed by drainage from the marshes, and attains its greatest height when the Gandak and the Ganges are both in flood ; it joins the latter river a few miles south of Dalsingh Sarai in Darbhanga District.

The most important of the minor streams are the Purana Dar Baghmati (an old bed of the Baghmati stretching from Mallahi on the frontier to Belanpur Ghat, where it joins the present stream) and the Adhwara. These flow southwards from Nepal, and are invaluable for irrigation in years of drought, when numerous dams are thrown across them. The largest sheet of water in the District is the Tal Baraila in the south ; its area is about 20 square miles, and it is the haunt of innumerable wild duck and other water-fowl.

The soil of the District is old alluvium ; beds of kankar or nodular limestone of an inferior quality are occasionally found. The District contains no forests ; and except for a few very small patches of jungle, of which the chief constituents are the red cotton-tree {Bombax malabaricuni), khair {^Acacia Caiechu), and sissu i^Dalbergia Sissoo), with an undergrowth of euphorbiaceous and urticaceous shrubs and tree weeds, and occasional large stretches of grass land inter- spersed with smaller spots of usar, the ground is under close cultiva- tion, and besides the crops carries only a few field-weeds. Near villages small shrubberies may be found containing mango, sissu, Eugenia Jambolana, various species of Pirns, an occasional tamarind, and^ a few other semi-spontaneous and more or less useful species.

The numerous and extensive mango groves form one of the most striking features of the District. Both the palmyra {Borassus flabellifer) and the date-palm {Phoenix sylvestris) occur planted and at times self-sown, but neither in great abundance. The field and roadside weeds include various grasses and sedges, chiefly species of Paniarni and Cyperus ; in waste corners and on railway embankments thickets of sissu, derived from both seeds and root-suckers, very rapidly appear. The sluggish streams and ponds are filled with water-weeds, the sides being often fringed by reedy grasses and bulrushes, with occasionally tamarisk bushes intermixed.

The advance of civilization has driven back the larger animals into the jungles of Nepal, and the District now contains no wild beasts except hog and a few wolves and nilgai. Crocodiles infest some of the rivers. Snakes abound, the most common being the karait {Bungarus caeruleus) and gohiiman or cobra {Naia tripudians).

Dry westerly winds are experienced in the hot season, but the temperature is not excessive. The mean maximum ranges from 73° in January to 97° in April and May, and falls to 74° in December, the temperature dropping rapidly in November and December. The mean mmimum varies from 49° in January to 79° in June, July, and August. The annual rainfall averages 46 inches, of which 7-4 inches fall in June, 12-4 in July, 11-3 in August, and 7-6 in September; cyclonic storms are apt to move northwards into the District in the two last-named months. Humidity at Muzaffarpur is on an average 67 per cent, in March, 66 in April, and 76 in May, and varies from 84 to 91 per cent. in other months.

One of the marked peculiarities of the rivers and streams of this part of the country is that they flow on ridges raised above the surrounding country by the silt which they have brought down. Muzaffarpur District is thus subject to severe and widespread inundations from their overflow. In 1788 a disastrous flood occurred which, it was estimated, damaged one-fifth of the area sown with Avinter crops, while so many cattle died of disease that the cultivation of the remaining area was seriously hampered. The Great Gandak, which was formerly quite unfettered towards the east, used regularly to flood the country along its banks and not infrequently swept across the southern half of the District.

From the beginning of the nineteenth century attempts were made to raise an embankment strong enough to protect the country from inundation, but without success, until in the famine of 1874 the existing embankment was strengthened and extended, thus effectually checking the incursions of the river. The tract on the south of the Baghmati is also partially protected by an embankment first raised in r8ro, but the dodb between the Baghmati and the Little Gandak is still liable to inundation. Heavy floods occurred in 1795, 1867, 1871, 1883, and 1898. Another severe flood visited the north of the District in August, 1902.

The town of Sltamarhi and the dodb between the Little Gandak and the Baghmati suffered severely, and it was reported that 60 lives were lost and 14,000 houses damaged or destroyed, while a large number of cattle were drowned. In Sltamarhi Itself 700 houses were damaged and 12,000 maunds of grain destroyed, and it was estimated that half of the maize crop and almost half of the m2rud crop were lost. Muzaffarpur town, which formerly suff"ered severely from these floods, is now protected by an embankment. One of the most disastrous floods known in the history of Muzaffarpur occurred in 1906, when the area inundated comprised a quarter of the whole District : namely, 750 square miles and over 1,000 villages, (ireat distress ensued among the cultivators, and relief measures were necessitated.

History

In ancient times the north of the District formed part of the old kingdom of Mithila, while the south corresponded to Vaisali, the capital of which was probably at Basarh in the Lal- ganj thatia. Mithila passed successively under the Pal and the Sen dynasties, and was conquered by Muhammad-i-Bakht- yar Khilji in 1203. From the middle of the fourteenth century it was ruled by a line of Brahman kings, until it was incorporated in the Mughal empire in 1556. Under the Mughals, Hajipur and Tirhut were separate sarkdrs ; and the town of Hajipur, which was then a place of strategical importance owing to its position at the confluence of the Ganges and the Gandak, was the scene of several rebellions.

After the acquisition by the British of the Diwani of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa in 1765, Siibah Bihar was retained as an independent revenue division, and in 1782 Tirhut (including Hajipur) was made into a separate Collectorate. This was split up in 1875 into the two existing Districts of Muzaffarpur and Darbhanga. During the Mutiny of 1857 a small number of native troops at Muzaffarpur town rose, plundered the Collector's house and attacked the treasury and jail, but were driven off by the police and decamped towards Siwan in Saran District without causing any further disturbance. Archaeological interest centres round Basarh, which has plausibly been identified as the capital of the ancient kingdom of Vaisali.

Population

The population of the present area increased from 2,246,752 in 1872 to 2,583,404 in 1881, to 2,712,857 in 1891, and to 2,754,790 in 1901. The recorded growth between 1872 and 1881 was due in part to the defects in the Census 01 1872. The District is very healthy, except perhaps in the country to the north of the Baghmati, which is more marshy than that to the south of it. Deaf-mutism is prevalent along the course of the Burhi Gandak and Baghmati rivers.

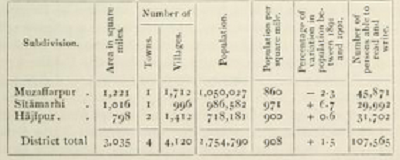

The principal statistics of the Census of 1901 are shown below : —

The four towns are Muzaffarpur, the head-quarters, Hajipur, Lalganj, and Sitamarhi. Muzaffarpur is more densely populated than any other District in Bengal. The inhabitants are very evenly distributed ; in only a small tract to the west does the density per square mile fall below 900, while in no part of the District does it exceed 1,000. Every thdtia in the great rice-growing tract north of the Baghmati showed an increase of population at the last Census, while every thima south of that river, except HajTpur on the extreme south, showed a decrease. In the former tract population has been growing steadily since the first Census in 1872, and it attracts settlers both from Nepal and from the south of the District. The progress has been greatest in the Sitamarhi and Sheohar thdnas which march with the Nepal frontier.

A decline in the Muzaffarpur thdna is attributed to its having suffered most from cholera epidemics, and to the fact that this tract supplies the majority of the persons who emigrate to Lower Bengal in search of work. The District as a whole loses largely by migration, especially to the metropolitan Districts, Purnea, and North Bengal. The majority of these emigrants are employed as earth- workers and /a/z^z-bearers, while others are shopkeepers, domestic servants, constables, peons, &c. The vernacular of the District is the Maithili dialect of Bihari. Musalmans speak a form of Awadhi Hindi known as Shekhoi or Musalmani. In 1901 Hindus numbered 2,416,415, or 87-71 per cent, of the total population; and Musalmans 337,641, or 12-26 per cent.

The most numerous Hindu castes are AhTrs or Goalas (335,000), Babhans (200,000), Dosadhs (187,000), Rajputs (176,000), Koiris (147,000), Chamars (136,000), and Kurmis (126,000) ; while Brahmans, Dhanuks, Kandus, Mallahs, Nunias, Tantis, and Telis each number between 50,000 and 100,000. Of the Muhammadans, 127,000 are Shaikhs and 85,000 Jolahas, while Dhunias and Kunjras are also numerous. Agriculture supports 76-4 per cent, of the population, industries 6-2 per cent., commerce 0-5 per cent., and the professions 0-7 per cent.

Christians number 719, of whom 341 are natives. Four Christian missions are at work in Muzaffarpur town : the German Evangelical Lutheran Mission, founded in 1840, which maintains a primary school for destitute orphans ; the American Methodist Episcopal Missionary Society, which possesses two schools ; a branch of the Bettiah Roman Catholic Mission ; and an independent lady missionary engaged in zatidna work.

Agriculture

The tract south of the Little Gandak is the most fertile and richest portion of the District. The low-lying dodb between Little Gandak and the Baghmati is mainly productive of rice, though rabi and bhadol harvests are also reaped. The tract to the north of the Baghmati contains excellent paddy land, and the staple crop is winter rice, though good rabi and bhadol crops are also raised in parts. In different parts of the District different names are given to the soil, according to the proportions of sand, clay, iron, and saline matter it contains. Ultimately all can be grouped under four heads : bahundar (sandy loam) ; maiiydri (clayey soil) ; bdngar (lighter than maiiyari and containing an admixture of sand) ; and lastly patches of usar (containing the saline efflorescence known as reK) found scattered over the District.

To the south of the Little Gandak balsufidar prevails, in the dodb the soil is chiefly matiydri, while north of the Baghmati bdngar predominates to the east of the Lakhandai river and matiydri to the west. Rice is chiefly grown on matiydri soil, but it also does well in low-lying bdngar lands, and the finer varieties thrive on such lands. Good rabi crops of wheat, barley, oats, rahar, pulses, oilseeds, and edible roots grow luxuriantly in balsundar soil, and to this reason is ascribed the superior fertility of the south of the District. Bhadoi crops, especially maize, which cannot stand too much moisture, also prosper in bahundar, which quickly absorbs the surplus water. Indigo does best in bahundar, but bangar is also suitable.

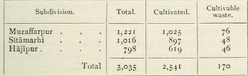

The chief agricultural statistics for 1903-4 are given below, areas being in square miles : —

It is estimated that 1,075 square miles, or 42 per cent, of the net cultivated area, are twice cropped.

The principal food-crop is rice, grown on 1,200 square miles, of which winter rice covers 1,029 square miles. The greater part of the rice is transplanted. Other food-grains, including pulses, khesdri, china, rahar, kodon, peas, oats, masuri, sdtvdn, kaunl, urd, mung, janerd {Holcus sorghum), and kurthi {Bolichos biflorus) cover 804 square miles. Barley occupies 463 square miles, a larger area than in any other Bengal District ; fnakai or maize, another very important crop, 256 square miles; marud, 129 square miles; wheat, 114 square miles; gram, 68 square miles; and miscellaneous food-crops, including alud or yams, suthni, and potatoes, are grown on 122 square miles.

Oil- seeds, principally linseed, are raised on 86 square miles. Other impor- tant crops are indigo, sugar-cane, poppy, tobacco, and thatching-grass. Muzaffarpur is, after Champaran, the chief indigo District in Bengal ; but its cultivation here, as elsewhere, is losing ground owing to the competition of the synthetic dye. European indigo planters have of late been turning their attention to other crops, in particular sugar-cane and rhea. Poppy is cultivated, as in other parts of Bihar, on a system of Government advances; the total area under the crop in 1903-4 was 12,400 acres, and the out-turn was 35 tons of opium. Cow-dung and indigo refuse are used as manure for special crops, such as sugar-cane, tobacco, poppy, and indigo.

Cultivation is far more advanced in the south than in the north of the District ; but up to the present there appears to be no indication of any progress or improvement in the method of cultivation, except in the neighbourhood of indigo factories. Over 2 lakhs of rupees was advanced under the Agriculturists' Loans Act on the occasion of the famine of 1896, but otherwise this Act and the Land Improvement Loans Act have been made little use of.

The District has always borne a high reputation for its cattle, and the East India Company used to get draught bullocks for the Ordnance department here. Large numbers of animals are exported every year from the Sitamarhi subdivision to all parts of North Bihar. It is said that the breed is deteriorating. In the north, floods militate against success in breeding ; and in the District as a whole, though there is never an absolute lack of food for cattle even in the driest season, the want of good pasture grounds compels the cultivator to feed his cattle very largely in his bathdn, or cattle yard. A large cattle fair is held at Sitamarhi every April.

The total area irrigated is 47 square miles, of which 30 are irrigated from wells, 2 from private canals, 6 from tanks or dhars, and 9 from other sources, mainly by damming rivers. There are no Government canals. In the north there is a considerable opening for the paifi and ahar system of irrigation so prevalent in Gaya District, but the want of an artificial water-supply is not great enough to induce the people to provide themselves with it.

Kankar, a nodular limestone of an inferior quality, is found and is used for metalling roads. The District is rich in saliferous earth, and a special caste, the Nunias, earn a scanty livelihood by extracting salt- petre ; 98,000 maunds of saltpetre were produced in 1903-4, the salt educed during the manufacture being 6,000 maunds.

Trade and Communication

Coarse cloth, carpets, pottery, and mats are manufactured ; pdlkis, cart-wheels, and other articles of general use are made by carpenters in the south, and rough cutlery at Lawarpur. But by most important industry is the manufacture of indigo. Indigo was a product of North Bihar long before the advent of the British, but its cultivation by European methods appears to have been started by Mr. Grand, Collector of Tirhut, in 1782. In 1788 there were five Europeans in possession of indigo works. In 1793 the number of factories in the District had increased to nine, situated at Daudpur, Sarahia Dhuli, Atharshahpur, Kantai, Motlpur, Deoria, and Bhawara. In 1850 the Revenue Sur- veyor found 86 factories in Tirhut, several of which were then used for the manufacture of sugar and were subsequently converted into indigo concerns.

In 1897 the Settlement officer enumerated 23 head factories, with an, average of 3 outworks under each, connected with the Bihar Indigo Planters' Association, besides 9 independent factories. The area under indigo had till then been steadily on the increase, reaching in that year 87,258 acres, while the industry was estimated to employ a daily average of 35,000 labourers throughout the year. Since then, owing to the competition of artificial dye, the price of natural indigo has fallen and the area under cultivation has rapidly diminished, being estimated in 1903-4 at 48,000 acres. Though only about 3 per cent, of the cultivated area is actually sown with indigo, the planters are in the position of landlords over more than a sixth of the District.

They are attempting to meet the fall in prices by more scientific methods of cultivation and manufacture, and many concerns now combine the cultivation of other crops with indigo. Indigo is cultivated either by the planter through his servants under the zirat or home-farm system, or else by tenants under what is known as the dsdvihvdr system {dsavii means a tenant), under the direction of the factory servants ; in both cases the plant is cut and carted by the planter. Under the latter system, the planter supplies the seed and occasionally also gives advances to the tenant, which are adjusted at the end of the year. The plant, when cut, is fermented in masonry vats, and oxidized either by beating or by currents of steam. The dye thus precipitated is boiled and dried into cakes. In 1903-4 the out-turn of indigo was 11,405 maunds, valued at 15-97 lakhs.

The recent fall in prices has resulted in the revival of the manu- facture of sugar. A company acquired in 1 900-1 the indigo estates of Ottur (Athar) and Agrial in Muzaffarpur and Siraha in Champaran District, for the purpose of cultivating sugar-cane. Cane-crushing mills and sugar-refining plant of the most modern type were erected at those places and also at Barhoga in Saran. These factories are capable of crushing 75,000 tons of cane in 100 working days, and of refining about 14,000 tons of sugar during the remainder of the year. Twelve Europeans and 500 to 600 natives a day are employed in the factories during the crushing season, and 10 Europeans and many thousands ot natives throughout the year on the cultivation of the estates and the manufacture of sugar. Besides this, the neighbouring planters contract to grow sugar-cane and sell it to the company. It is claimed that the sugar turned out is of the best quality, and a ready sale for it has been found in the towns of Northern India.

The principal exports are indigo, sugar, oilseeds, saltpetre, hides, ght, tobacco, opium, and fruit and vegetables. The main imports are salt, European and Indian cotton piece-goods and hardware, coal and coke, kerosene oil, cereals, such as maize, millets, &c., rice and other food- grains, and indigo seed. Most of the exports find their way to Cal- cutta. The bulk of the traffic is now carried by the railway ; and the old river marts show a tendency to decline, unless they happen to be situated on the line of railway, like Mehnar, Bhagwanpur, and Bairagnia, which are steadily growing in importance.

Nepal exports to Muzaffarpur food-grains, oilseeds, timber, skins of sheep, goats, and cattle, and saltpetre ; and receives in return sugar, salt, tea, utensils, kerosene oil, spices, and piece-goods. A considerable cart traffic thus goes on from and to Nepal, and between Saran and the north of the District. The chief centres of trade are Muzaffarpur town on the Little Gandak (navigable in the rains for boats of about 37 tons up to Muzaffarpur), HajTpur (a railway centre), Lalganj (a river mart on the Great Gandak), Sitamarhi (a great rice mart), Bairagnia and Sursand (grain marts for the Nepal trade), Mehnar, Sahibganj, Sonbarsa, Bela, Majorganj, Mahuwa, and Kantai. The trade of the District is in the hands of Marwaris and local Baniya castes.

The District is served by four distinct branches of the Bengal and North-Western Railway. The first, which connects Simaria Ghat on the Ganges with Bettiah in Champaran District, runs in a south-easterly direction through Muzaffarpur District, passing the head-quarters town. The second branch enters the District at the Sonpur bridge over the Great Gandak, passes through Hajipur, and runs eastwards to Katihar in Purnea District, where it joins the Eastern Bengal State Railway ; it intersects the first branch at Baruni junction in Monghyr District.

The third runs from Hajipur to Muzaffarpur town, thus connecting the first two branches. The fourth, which leaves the first-mentioned branch line at Samastipur in Darbhanga District, enters Muzaffarpur near Kamtaul and passing through Sitamarhi town has its terminus at Bai- ragnia. Communication with that place is, however, at present kept open only during the dry season by a temporary bridge over the Bagh- mati about 3 miles away ; but the construction of a permanent structure is contemplated.

The District is well provided with roads, and espe- cially with feeder roads to the railways. Including 542 miles of village tracks, it contains in all 76 miles of metalled and 1,689 niiles of unmetalled roads, all of which are maintained by the District board. The most important road is that from HajTpur through Muzaffarpur and Sitamarhi towns to Sonbarsa, a large mart on the Nepal frontier. Important roads also connect Muzaffarpur town with Darbhanga, Motl- hari, and Saran, 11 main roads in all radiating from Muzaffarpur.

The subdivisional head-quarters of Hajipur and Sitamarhi are also connected by good roads with their police ihdnas and outposts. Most of the minor rivers are bridged by masonry structures, while the larger ones are generally crossed by ferries, of which there are 67 in the District. The Little Gandak close to Muzaffarpur town on the Sitamarhi road is crossed by a pontoon bridge 850 feet in length.

During the rainy season, when the rivers are high, a considerable quantity of traffic is still carried in country boats along the Great and Little Gandak and Baghmati rivers. Sal timber {Shorea robusta) from Nepal is floated down the two latter, and also a large quantity of bamboos. The Ganges on the south is navigable throughout the year, and a daily service of steamers plies to and from Goalundo.

Famine

The terrible famine of 1769-70 is supposed to have carried off a third of the entire population of Bengal. Another great famine occurred in 1866, in which it was estimated that 200,000 people died throughout Bihar ; this was especially severely felt in the extreme north of the District, Muzaf- farpur again suffered severely in the famine of 1874, when deficiency of rain in September, 1873, and its complete cessation in October, led to a serious shortness in the winter rice crop. Relief works were opened about the beginning of 1874. No less than one-seventh of the total population was in receipt of relief.

There was some scarcity in 1876, when no relief was actually required; in 1889, when the rice crop again failed and relief was given to about 30,000 persons ; and in 1 89 1-2, when on the average 5,000 persons daily were relieved for a period of 19 weeks. Then came the famine of 1896-7, the greatest famine of the nineteenth century. On this occasion, owing to better communications and their improved material condition, the people showed unexpected powers of resistance.

Three test works started in the Sitamarhi subdivision in November, 1896, failed to attract labour, and it was not till the end of January that distress became in any sense acute. The number of persons in receipt of relief then rose rapidly till the end of May, when 59,000 persons with 4,000 dependants were on relief works, and 59,000 more were in receipt of gratuitous relief. The number thus aided increased to 72,000 in July, but the number of relief workers had meanwhile declined, and the famine was over by the end of September. The total expenditure on relief works was 5'64 lakhs and on gratuitous relief 4-91 lakhs, in addition to which large advances were made under the Agriculturists' Loans Act. The import of rice into the District during the famine was nearly 33,000 tons, chiefly Burma rice from Calcutta. The whole of the District suffered severely, except the south of the HajTpur subdivision, but the brunt of the distress was borne by the Sitamarhi subdivision.

Administration

For administrative purposes the District is divided into three sub- divisions, with head-quarters at Muzaffarpur, Hajipur, and Sita- MARHi. The staff subordinate to the District Magistrate-Collector at head-quarters consists of a Joint-Magistrate, an Assistant Magistrate, and nine Deputy-Magistrate-Collectors, while the Hajipur and Sitamarhi subdivisions are each in charge oi an Assistant Magistrate-Collector assisted by a Sub-Deputy-Collector. The Superintending Engineer and the Executive Engineer of the Gandak division are stationed at Muzaffarpur.

The civil courts are those of the District Judge (who is also Judge of Champaran), three Sub-Judges and two Munsifs at Muzaffarpur, and one Munsif each at Sitamarhi and Hajipur. Criminal courts include those of the District and Sessions Judge and District Magistrate, and the above-mentioned Joint, Assistant, and Deputy-Magistrates. When the District first passed under British rule it was in a very lawless state, overrun by hordes of banditti. This state of affairs has long ceased. The people are, as a rule, peaceful and law-abiding, and heinous offences and crimes of violence are comparatively rare.

At the time of the Permanent Settlement in 1793 the total area of the estates assessed to land revenue in Tirhut was 2,476 square miles, or 40 per cent, only of its area of 6,343 square miles, and the total land revenue was 9-84 lakhs, which gives an incidence of 9 annas per acre ; the demand for the estates in Muzaffarpur District alone was 4-36 lakhs. In 1822 operations were undertaken for the resumption of invalid revenue-free grants, the result of which was to add 6-77 lakhs to the revenue roll of Tirhut, of which 3-18 lakhs fell to Muzaffarpur. Owing to partitions and resumptions, the number of estates in Tirhut increased from 1,331 in 1790, of which 799 were in Muzaffarpur, to 5,186 in 1850. Since that date advantage has been taken of the provisions of the partition laws to a most remarkable extent, and by 1904-5 the number of revenue-paying estates had risen to no less than 21,050, a larger number than in any other Bengal District. Of the total, all but 49 with a demand of Rs. 16,735 were permanently settled. The total land revenue demand in the same year was 9-78 lakhs. Owing to the backward state of Tirhut at the time of the Permanent Settlement, the incidence of revenue is only R. 0-9-6 per cultivated acre.

A survey and preparation of a record-of-rights for Muzaffarpur and Champaran Districts, commenced in 1 890-1 and successfully com- pleted in 1 899-1 900, is important as being the first operation of the kind which was undertaken in Bengal for entire Districts which came under the Permanent Settlement. The average size of a ryot's holding in Muzaffarpur was found to be 1-97 acres, and 82 per cent, of them were held by occupancy and settled ryots. Such ryots almost always pay rent in cash, but one-fifth of the non-occupancy ryots and three- fifths of the under-ryots pay produce rents. These are of three kinds, batai^ bhaoli, and mankhap ) in the first case the actual produce is divided, generally in equal proportions, between the tenant and the landlord ; in the second the crop is appraised in the field and the land- lord's share paid in cash or grain ; while in the third the tenant agrees to pay so many maunds of grain per bigha.

The average rate of rent per acre for all classes of ryots is Rs. 4-0-1 1. Ryots holding at fixed rates pay Rs. 2-11-11 ; occupancy ryots, Rs. 3-12-3; non-occupancy ryots, Rs. 4-9-6 ; and under-ryots, Rs. 4-5-8 per acre. The rent, how- ever, varies not only with the character and situation of the land, but also according to the caste and position of the cultivator, a tenant of a high caste paying less than one of lower social rank. Rents are higher in the south than in the north, where the demand for land has developed at a comparatively recent date. The highest rents of all are paid in the neighbourhood of Hajipur, where poppy, tobacco, potatoes, (Sec, are grown on land which is never fallow and often produces four crops a year.

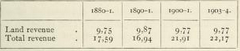

The following table shows the collections of land revenue and of total revenue (principal heads only), in thousands of rupees : —

Outside the municipalities of Muzaffarpur, Hajipur, Lalganj,and Sitamarhi, local affairs are managed by the District board, with subordinate local boards in each subdivision. In 1903-4 its income was Rs. 3,31,000, of which Rs. 1,83,000 was derived from rates; and the expenditure was Rs. 3,60,000, the chief item being Rs. 2,69,000 expended on public works.

The most important public works are the Tirhut embankment on the left bank of the Great Gandak, and the Turk! embankment on the south bank of the Baghmati. The Gandak embankment, which runs for 52 miles from the head of the Baya river to the confluence of the Gandak and Ganges, and protects 1,250 square miles of country, is maintained by contract. On the expiry of the first contract in 1903, a new contract for its maintenance for a period of twenty years at a cost of 2-g8 lakhs was sanctioned by Government. The TurkI em- bankment, originally built in 18 10 by the Kantai Indigo Factory to protect the lands of that concern, was acquired by Government about 1S70. It extends from the Turk! weir for 26 miles along the south bank of the Baghmati, and protects 90 square miles of the dodb between that river and the Little Gandak. In 1903-4 Rs. 2,200 was spent on its maintenance.

The District contains 22 police stations and 14 outposts. The force subordinate to the District Superintendent consists of 3 inspectors, 28 sub-inspectors, 47 head constables, and 432 constables ; the rural police force is composed of 238 daffaddrs and 4,735 chaukiddrs. A District jail at Muzaffarpur has accommodation for 465 prisoners, and subsidiary jails at Hajipur and Sitamarhi for 38.

The standard of literacy, though higher than elsewhere in North Bihar, is considerably below the average for Bengal, only 3-9 per cent, of the population (7-8 males and 0-3 females) being able to read and write in 1901. The number of pupils under instruction, which was 24,000 in 1880-1, fell to 23,373 in 1892-3, but increased to 29,759 in 1 900-1. In 1903-4, 35,084 boys and 1,843 gi^^s were at school, being respectively 17-7 and 0-85 per cent, of the children of school-going age. The number of educational institutions, public and private, in that year was 1,520, including one Arts college, 20 secondary, 1,013 primary, and 486 special schools. The expenditure on education was 1-55 lakhs, of which Rs. 11,000 was met from Provincial funds, Rs. 53,000 from District funds, Rs. 3,000 from municipal funds, and Rs. 57,000 from fees. The most important institutions are the Bhuinhar Brahman College and the Government District school at Muzaffarpur town.

In 1903 the District contained five dispensaries, of which three had accommodation for 62 in-patients. The cases of 72,000 out- patients and 800 in-patients were treated, and 4,000 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 13,000, of which Rs. 900 was met from Government contributions, Rs. 5,000 from Local and Rs. 4,000 from municipal funds, and Rs. 3,000 from subscriptions. Besides these, two private dispensaries are maintained, one at Baghi in the head-quarters subdivision and the other at Parihar in the Sita- marhi subdivision, by the Darbhanga Raj.

Vaccination is compulsory only in municipal areas. In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 87,000, representing 32 per 1,000 of the population, or rather less than the average for Bengal.

[L. S. S. O'Malley, District Gazetteer (Calcutta, 1907) ; C. J. Steven- son-Moore, Settlement Report {Cdlcwiia., 1900).]